In the last issue, we introduced the history of “Dear Comrades,” a readers’ letters section inspired by pages from the Italian newspaper Lotta Continua. Grappling with a changing class composition, their organization solicited writings from an increasingly heterogeneous base of workers, making space for deeper political coordination across the class. Reviving that practice here, we present six more dispatches, each from a sectoral struggle with an immediate relationship to the state.

In the last issue, we introduced the history of “Dear Comrades,” a readers’ letters section inspired by pages from the Italian newspaper Lotta Continua. Grappling with a changing class composition, their organization solicited writings from an increasingly heterogeneous base of workers, making space for deeper political coordination across the class. Reviving that practice here, we present six more dispatches, each from a sectoral struggle with an immediate relationship to the state.

Mujeres Unidas y Activas: Immigrant Domestic Workers and Self-Organization

Part workers’ center and part domestic violence resource center, the Mujeres Unidas y Activas space in East Oakland is demonstrating what it means to build a Latina immigrant women’s’ organization. And I am lucky enough to work with them.

I first heard about MUA not long after moving to Oakland when a few members shared the palabra at a show featuring “Las Cafeteras.” Speaking to a full house, the mujeres talked about their campaign to educate and organize Bay Area domestic workers in the aftermath of the passage of AB 241, also known as the California Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. The bill of rights, which was signed into law by the governor in January after many years of struggle by domestic workers and their allies, is estimated to cover 100,000 workers, many of whom are immigrant Latina and Asian women both documented and undocumented. For the first time ever, many personal care workers in the state are now legally protected while working overtime. AB241 is an historic victory for care laborers as it represents the inclusion of a segment of workers traditionally exempt from labor protections in US history.

Yet, the law in many ways continues to reproduce the second-class status of domestic workers. First, because it was defanged by CA democrats who took out provisions for mandatory meal and rest breaks. Secondly, it was cynically scheduled to sunset, or expire, after only three years. And ultimately it will be very difficult for the state to enforce. In New York, the only other state to have passed similar legislation, domestic workers may have earned the same legal protections as other workers, but there remains a host of unresolved grievances. A survey showed that only 15% of employers of nannies paid their employees overtime a little over a year after the bill.

Employer’s inclination to sidestep overtime pay is only exacerbated by the looming sunset date in California. Even with domestic workers’ bill of rights, many will retain a legitimate fear of being fired in an industry where employers often get away with egregious offenses in the isolated privacy of their homes, against a workforce historically viewed by the state as second-class. For undocumented domestic workers, citizenship issues obviously also raise legitimate fears of deportation. Coupled with language barriers, racism, and a culture of sexual harassment, a temporary law granting rights to overtime pay is symbolic at best.

Nevertheless, organizations of domestic workers and their allies are keeping their eyes on the prize, riding on the coattails of the legislative victory. MUA, as part a statewide coalition called the California Domestic Workers Coalition just celebrated its one year anniversary, rallying around 350 women to the event. One MUA staff member told me she invited 150 of them personally and the rest found ways to tag along with their friends. I’ve personally witnessed dozens of examples of this kind of politicization take place in my short time at MUA.

Witnessing the self-organization of these women day in and day out, the ways friends and oftentimes strangers become companeras in solidarity with one another, I believe they are really building toward their goal of organizing 10-20% of California’s domestic workers by 2017. Not only that, but they are building the capacity to really end the second-class treatment of domestic workers, even as Democrats like Jerry Brown try to protect wealthy employers. In the midst of statements like Brown’s – that the state can’t raise the standard of living for domestic workers because it would be detrimental to California’s economy – California domestic workers and allies make this bold statement:

Together we won dignity, respect, and basic protections for California Domestic Workers… Now we will work to educate the public and ensure that these rights are respected and keep organizing to defend the workers that make all other work possible.

In fact, many of MUA’s members, I have found, talk about their work as care laborers, both paid and unpaid (that is, personal care assistants and/or unpaid mothers) in terms of pride and dignity. Their experiences tell stories of hyper-exploited laborers who suffer physical, emotional, and sexual abuse because they care so much about their children, their partners, and the people who they care for — be they the elderly, the children of “working women” and/or people with disabilities. And MUA turns this care work inwardly at domestic workers themselves – building networks of self-care and investment in each other’s shared liberation.

A life worth living won’t be won through increased state vigilance for these women. Instead, it’ll be guaranteed in support groups and political education, where companeras support one another in pushing back against domination and exploitation – whether protecting each other from domestic partners or demanding their right to overtime pay. These fights, waged in the personal and intimate workplaces of each woman, lay the groundwork for future struggle. Dehumanizing stereotypes of Latina immigrant women are leveraged to justify austerity, militarized borders, wage theft, and state-sponsored violence in the home. In turn, these conditions discipline the labor force, and invite representations of women that enable even more violence. But MUA’s self-organization subverts the production of docility, in representation and work regime alike.

- MM

Gentrification, Privatization, and a Class Struggle

It’s clear to those of us paying attention that gentrification is hitting the Bay Area particularly hard. The Bay is a region where over 40% of venture capital circulates seeking profitable investment, creating the drive among the political sections of the ruling class to capture portions of this growing bubble of money. Politicians across Bay Area cities are coming together to reconfigure cities from San Francisco to San Jose in terms of transit, jobs, and housing through “specific areas plans” that are set to coordinate the circulation of financial capital through urban space.

This circulation of financial capital has weaknesses - points of potential interruption where the linkage between the physical spaces that it seeks to legally control and materially develop can be subverted. Unfortunately, most of the time, the strategies for fighting gentrification have failed to impede this cycle of investment and production, usually waiting too long to really block the circulation of finance and thereby forced to mitigate the impacts of financial investment and property development instead. Community coalitions, nonprofits, housing organizations, and others have attempted to pass laws at the municipal level to protect renters from harassment, stop evictions of individual residents, and pool resources to buy individual plots of land.

All of these approaches have some validity in the sense that they are expressions of people attempting to dig in their collective heels against the onslaught of financial capital, property developers, and municipal politicians eager to knock us down and move us out of the way. But what’s missing from that anti-gentrification equation? How can we actively stop the material processes of gentrified production, as well as interrupt the flows of finance that seek to initiate the circuit of property development? What are the role of workers at the workplace in fighting against the capitalist process of urban redevelopment?

Privatization of Public Land and Gentrification

One example can be found just east of Lake Merritt. During the course of the past few months, the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) has attempted to initiate a public-private partnership with property developers to redevelop a two block area of lakeside property on 2nd Ave. This area of land houses both the former OUSD administration building (which was taken out of commission last year due to a mysterious flood in its basement level) and a continuation high school called Dewey Academy.

In 2012, the City of Oakland took the initiative through the Lake Merritt Station Area Plan (one of the specific plans, similar to the West Oakland Specific Plan) to label the two block radius of OUSD land as an “opportunity site” for “urban residential housing” without consulting any of the OUSD workers, students or community members prior to doing so. However, this went more or less completely unknown to the community until this past May when the OUSD convened a committee to determine what to do with the 2nd Ave. land. OUSD issued an RFQ, or Request for Developer Qualifications, which essentially put the 2nd Ave. land on the market for developers to begin eyeing for redevelopment. At the first meeting of this committee, a property developer from the UrbanCore LLC group presented their proposed 24 story luxury apartment development next door to the school district’s land and made clear their intention to “find out what’s happening with the continuation school next door to our development.”

Independent Committee of Students and School Workers

At this point a group of education workers at the surrounding schools (there are 3 schools in a one block radius of the 2nd Ave. area) caught wind of the school district’s plans for redeveloping the space and began organizing. These school workers – mostly support staff and teachers, both unionized and unionized – came together and wrote a series of articles denouncing the plans for redevelopment, and exposing the role this privatization deal would play in the ongoing gentrification of Oakland.

While school was out during the bulk of this activity, the school workers called together a committee of after-school educators, unionized teachers, nonprofit workers, and students to strategize a fightback against the privatization and gentrification of public space. They met independently and organized a series of direct actions over the course of a month and a half.

The first action was a public bbq on the school district’s land. While this action was organized on a workday, a Monday, they still managed to mobilize over 100 people - a majority of whom were students and employees of the OUSD, along with healthcare workers, nonprofit employees and community members concerned about the privatization and gentrification of the public space.

Over 20 students, school workers, and community members showed up at the district headquarters in downtown Oakland to crash a meeting of district officials and developers interested in the land. When the group arrived, they found that the district had rescheduled the meeting at the last minute, presumably to avoid the disruption of the school workers and students against privatizing the land. Not wanting to lose their moment, the students and workers sought out the president of the school board’s office and demanded a meeting with him. He came out, reluctantly, and introduced the group to the woman he had been meeting with: a paid consultant hired to carry out the OUSD’s official “community engagement process” for the price of $40,000.

Attempted Co-Optation by the District and the Persistence of Independent Organizing

This community engagement process was initiated as a direct response to the independent organization of school workers and students against the privatization plan. It was intended to bring the insurgent employees and students back under the wing of the school district. Board of Education members expressed their wish to engage in restorative justice to address the “harm” that the school district had caused to the community through their backroom dealings with property developers like UrbanCore LLC. However, the independent committee of students and school workers refused to disband in response to the community engagement process and continued to organize actions at the school board, releasing public statements criticizing the district’s moves as well as updating the broader community on the new phases of the anti-privatization campaign.

Due to these various actions and public critiques, the independent committee won a partial victory: it temporarily delayed the development plan and created broader awareness and public opinion about the redevelopment plan and its relation to the gentrification of the city. All of this happened within the course of two months during the summer, before school started back up. Furthermore, of the 12 property developers present at the first series of district-developer (read: public-private) meetings, only 4 actually submitted proposals.

After the summer came to an end, some interesting things happened among the school workers, in particular the unionized teachers. A meeting of unionized educators was called to discuss the issue. However, this meeting of rank and file union members was not called by an active member of the independent committee against the redevelopment plan, nor was it initiated by the union itself. Instead, it was called by an educator who had not at all been involved in the plan. While the union leadership was dragging its feet on issuing an endorsement of the independent committee’s demands to stop the privatization deal, this rank and file school worker called the meeting in order to bring together members of the three schools in the East Lake area in order to discuss what all the school workers of that area could do to further organize their co-workers against the redevelopment plan. Additionally, each of the schools represented voiced their concerns and critiques over the way in which the consultant carrying out the community engagement was attempting to field the school worker’s questions but providing zero answers.

The workers at this meeting decided to continue mobilizing their coworkers independently of the district’s attempt to “engage” them so that they could put forward an independent voice from the rank and file of school workers. Additionally, they decided that they would engage not only their fellow union members, but also create spaces for discussion among the custodians, food service, and other classified staff at their workplaces.

Where Are We Now?

This story is not at all over. The land in question has not yet been sold off or leased, and the process has slowed down. But the district has so far refused to rescind their RFQ or formally end the marketization of the land that initiated the outrage among students and school workers.

While this small case study does not in any way provide conclusive strategy for fighting gentrification and privatization, the struggle of the past few months east of Lake Merritt has raised some interesting prospects, particularly around fighting the privatization of public land and resources.

Participants in the organizing have learned the importance of creating organizing spaces independent of the school district, despite the school district’s savvy attempts at co-optation through rhetorical strategies of “restorative justice” and “harm reduction.”

Union members have begun learning the lesson of getting organized across workplaces on an independent basis, without waiting for the mediation of the union bureaucracy, as well as the importance of engaging in strategic conversations with all workers – unionized and not.

The ongoing alliances of students and school workers puts into question the conventional wisdom of right-wing teacher bashers who see teachers as inherently selfish, greedy, and narrowly concerned with their own standard of living, as well as “left-wing” critiques of teachers who see them one-sidedly as agents of the state in relation to their students. Instead, we’ve seen mutually flourishing relationship between militant students and activated school workers that point toward possibilities of new solidarities in struggles against privatization and gentrification for this struggle as well as future workplace battles.

- Members of Advance the Struggle

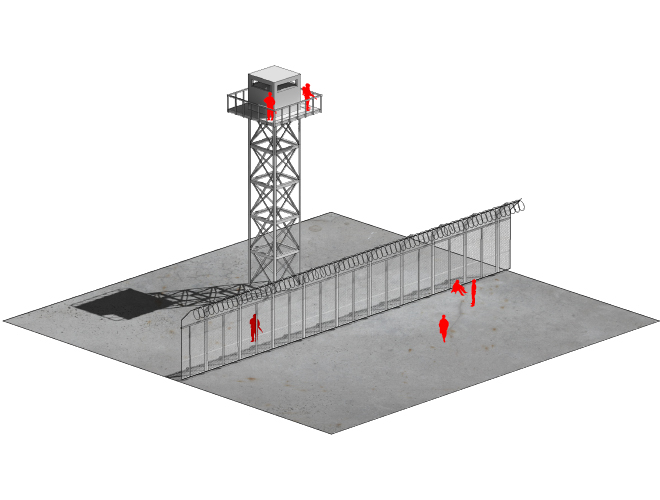

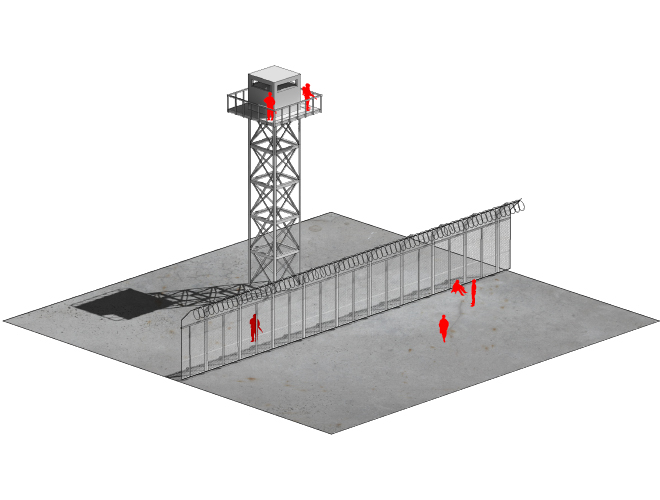

We’re confirming an ideological belief about prisons and jails

The idea of providing immediate services to those locked up in jails and prisons is sometimes seen as a compelling and essential way to reach people inside. But what are the inherent risks? It may feel like we are empowering people by giving them positive outlets and time around people who see them as equal and human. It can also provide resources for organizing behind bars. But this service work, which many invested in prison abolition do, allows the jails and prisons to expand. The state lays claim to the work of those resisting inside and outside prisons to justify the need for more money – all in the name of making friendlier cages. We saw this last year when, instead of decarcerating thousands of people, the state of California distributed millions of dollars to expand jails, with the money awarded to the best reform program proposed by county sheriffs.

This is a self-defeating way for the movement to work, and by allowing this co-optation to happen, we’re confirming an ideological belief that correctional officers care about more than their “job security.” For abolitionists there is a constant question of how to best serve communities of people locked up. On the one hand, we want to connect with and provide support to people while they serve their time; on the other hand, we want to do away with policing and prisons altogether. In light of this contradiction, we have to remember that these institutions work the way they are supposed to – they don’t target communities of color and working class neighborhoods by accident, it’s an intentional strategy to discipline these folks. If you choose to work within prisons and jails by partnering with them, you’re lending credence to the idea that these institutions can work, advancing reform and growth. But not abolition.

Then the question becomes: how can we link up with prisoners without justifying their imprisonment?

- Misty Rojo, Campaign and Communications Director at Justice Now

When We Said Not One More Deportation, We Actually Meant It

When I first heard the word “DREAMer” I didn’t think it was a problematic term, nor did I think it would have a negative impact on our movement. The language came from legislation in Washington and it referred to undocumented youth under 31, who came to the US under the age of 16, and had completed high school with a “college ready” GPA. I remember being in conversations with other community organizers and debating whether this term was appropriate for us to identify with. Back in 2010 I did not know its history; I just knew that it was catchy and it got us attention. As I learned more about the movement and affiliated myself with grassroots groups doing this work across the country, I learned that DREAMer was actually a really problematic term. It was coined by a white legislator in an attempt to create sympathy for some undocumented youth. In turn, the time the only people who were allowed to be media spokespeople were youth either in college or on track to be. They were the ones chosen to represent us in Congress.

If at first the DREAMer narrative was strategic, then it quickly became annoying. As our movement picked up steam, the word DREAMer became exactly what legislators wanted it to be – an exclusive term for those who are model residents and future “Americans.” We began to see how quickly people were ready to throw our parents and “criminals” under the bus. For people who live in low income communities of color the reality was that most youth do not fit into the DREAMer identity. And neither did we.

Nonprofits pushed a narrative in which we had no agency in coming to this country. So who was to blame? Our parents. The dreamer narrative served as a wedge between youth who qualify for the DREAM Act and the rest of the community who didn’t. This exclusion extended to people with criminal records, prior deportations, and people who did not fit the age requirement to name a few. It became more and more apparent that if left in the hands of “advocates,” our humanity would be defined by a piece of legislation, one that they could use for their own agenda while also doing what “advocates” do best: make concessions to the state.

As our movement evolved so too did the DREAMer. DREAMer became synonymous for “non-threatening” and “cute” in the eyes of the system.

We soon realized that DREAMer, instead of being something empowering, set a standard for undocumented youth. The expectation was to complete a four year degree in communities where the system historically has been set up for just a few to succeed. It makes it so that in order to be considered a DREAMer, one must pursue education and only through demonstrating an ability to endure and survive the institutions of higher learning can someone become desirable in this society. The DREAMer term adds stress to immigrant youth who face a myriad of issues when attending school in the United States. The pressure to assimilate, the need to learn the language, bullying, criminalization and achievement in school, all lead many undocumented youth to fall into depression and other health issues. During our “coming out” of the shadows events I heard high school age youth expressing a lack of motivation to share their stories, feeling unworthy of recognition because they did not have good grades.

Organizations such as United We Dream and other DREAM advocacy organizations were conservative compared to undocumented grassroots struggle. We learned that some of those grassroots organizations pushing the DREAMer narrative were actually led and taken over by people with papers. So it was easy to connect the dots, associating the DREAMer narrative with conservative view on immigration.

During a collaboration with one of these organizations, I was sharing information on how the Immigrant Youth Coalition takes on, or selects, deportation campaigns. I told them I believed that we should never turn anyone away. But I was quickly interrupted by an “advocate” who said, “What about child molesters and rapists? They should be deported.” I was not surprised, but I told them that as organizers, you organize the people. You can’t pick and choose who you fight for, and they can’t stay in the DREAMer mentality and start picking and choosing which group of oppressed people you fight for. When we said “Not One More Deportation,” we actually meant it. If people commit an offense, violent or not, they should face justice and be held accountable by the community that was affected. Obviously, we understand our criminal justice system is unjust, but for many people, it’s a better option than being deported to a place they fled to survive. Challenging the DREAMer narrative is essential to dismantling the criminalization and elitism found in the immigrant rights movement. Many youth have seen the problems with DREAMer and have actively challenged it, while others like myself take offense since it shows a lack of understanding of how we live everyday as undocumented people.

In order to create a space in the movement for undocumented youth, we need to accept all that an undocumented person was, is, and could be. This means fighting for everyone, regardless of their past, regardless of their mistakes or misfortunes.

– Jonathan Perez, Founder of Immigrant Youth Coalition

Organizing Nonprofit Workers

As a Guatemalan third-world left feminist with Marxist tendencies, I organize knowing the enemy: a small group of Imperialist Capitalists with the only intention of growing their profits via the exploitation of the working class. Yet I’m constantly reflecting on the following questions: is change possible doing non-profit work? How can I survive by just being a community organizer? How can I keep working and organizing without burning out?

As I became politicized, I wanted my daily work to benefit struggle. Nonprofits seemed like a way to survive while contributing to my community. I was very hopeful of my decision until I began working for the industry, where it became clear that its workers and its “constituents” were exploited under the rhetoric of social justice.

Because of their funding structure nonprofits are instruments of their biggest donors: capitalists and the state. They were created by big foundations during the height of social struggle in 1960’s, when foundations and private venture businesses were organized under a tax code 501(c)(3). This status enabled them to pay less taxes, and became a convenient investment opportunity for surplus capital. By the 1980’s with the rise of neoliberal austerity, nonprofits became of a critical value to the state, taking over some of the functions of social reproduction that the government had retreated from. Though some radical grassroots organizing had moved into nonprofit work to avoid criminalization and create institutionalization, their work was easily co-opted to silence their voices, dictated increasingly by grant providers. Nonprofits cannot be critical of the capitalist state, its police, prisons, and fences since the interests of most philanthropists aligns with that of the state: maintaining the status quo of capitalism. It’s more about managing the social problems created by this racist capitalist system more than it is about empowering people to abolish that system.

Thankfully I’ve stayed grounded and accountable to struggle outside of the nonprofit industrial complex. Four years ago coming out of undergraduate school back to my community of East Los Angeles some of my friends and I decided to organize a collective. A grassroots collective consisting of community education to raise awareness about different issues to take social action. The collective is known as Community Education for Social Action (CESA) and is able to work on issues of environmental justice, gentrification, and police brutality. It is all volunteer run but it helps us learn how to work together with the motivation for social justice and not money. Over these four years we have met other people and collectives in the community of East L.A. with similar goals and we have worked together. I like to think that this is the meaningful work we should all be doing to change the oppressive systems that are in place affecting working-class people of color.

Though nonprofits themselves are not institutions we can count on, organizing nonprofit workers could have profound effects on social struggle. As an individual nonprofit wage earner, leveraging what little power I have in my workplace has helped bring more critical politics to my co-workers, which in turn shapes our organizations work. In turn, I’ve used resources to amplify CESA’s work with my community, without the constraints of our donors. Nonprofits are funded in part by taxes, which are my stolen wages, so I take the position to appropriate what is ours. I do this by using the materials my work provides. On a more coordinated basis, though, with nonprofit workers across a city, this could be a substantial avenue for expanding the grassroots work we do on the ground. An organized workforce might be able to hold the boss accountable to selecting donors, or at the very least would provide a buffer against exploitative workplace environments that encourage you to work far beyond your capacity. We ought to save our energy for the truly transformative struggle. I work at what other collectives are doing and we have a working relationship; however, I am careful about co-optation, because we as collectives want to remain autonomous and not be regulated by the state.

My weeks are full of street activities that I look forward to. I go and work for a nonprofit where I meet youth and community and I can share what we do after 6pm. I go home tired but I know we are planting the seeds or watering the work that was done by past generations before us and before the nonprofit industrial complex. As collectives, we have been able to open up community spaces, coordinate bicycle coalitions, create community gardens, and transform Prospect Park in Boyle Heights to the People’s Park. We have learned that we need to build community among one another and protect our streets not against each other but against law enforcement that profiles our youth and kills innocent people. We are building relationships with the families that have been affected by police brutality. The list goes on but we would not be able to do what we do if the activities were controlled by the nonprofit system influenced by a capitalist system.

- Carla Osorio Veliz, MSW

A Testament to the Deep Fragmentation

Sin Barras is a prison abolition group based in Santa Cruz, California. We are not a registered non-profit, receive no government or foundation funding, and are unstaffed. We say this immediately because we are organizing in a moment of neoliberal non-profits and constant co-optation, so “grassroots” does not get the point across.

We are celebrating a recent victory that has improved medical conditions and treatment inside the Santa Cruz County Main Jail. Our celebration is not an endpoint, but a moment of re-invigorated energy, which we are using to reflect on our strategies and learn our next steps. We are trying to hold systems of incredible violence accountable and at the same time are working to render them obsolete. But one clear takeaway is that a militant and community-oriented direct action led to a year-long grand jury investigation of the inhumane conditions in our local jail. Of course the work continues, because we know deeply that the jail itself is inhumane.

Our organization began with four or five university students excited about the project of prison abolition. We had all experienced the dehumanizing process of being arrested and/or had family members incarcerated, and though we were students, made a commitment to root our movement-building in the broader Santa Cruz community. Slowly but surely we have grown into a fierce network that actively amplifies the knowledge and organizing capacity of people who have been most directly impacted by police and prison violence, white supremacy, and the poverty created by capitalism.

Sin Barras promotes community-based interventions that confront interpersonal harm without relying on the police. We fight for prisoner rights and support prisoners’ struggles through art, direct action, and legal strategies that tackle “non-reformist reforms,” reforms that do not participate in criminalization or compromise. It takes a variety of tactics to make visible the lived realities and resiliency of people who have been caged and rendered disposable by the state. It is no coincidence that while California has built 24 new prisons in the last 30 years, most formerly incarcerated people and their loved ones have been coercively conditioned into less vocal and direct forms of resistance. This is done by the police, our current education system, the courts, and the prisons. Because of this reality, it is crucial that those most impacted by the systems we are fighting are at the forefront and center of our movements, working to sustain a statewide coalition of anti-prison organizations. This leadership model is crucial to combat the story liberal social movements so often mobilize, painting victims of oppression so they match national norms about what “deserving citizens” are like. These constituents are portrayed as “non-criminals,” with documentation, conforming to white, capitalist, and patriarchal norms. When these strategies are used, the most dangerous conditions and the people who are currently most vulnerable cannot be discussed or addressed and are cast as “undeserving.”

While we maintain and develop our own analysis of an abolitionist future, we have learned that working together across our geographies and political nuances is effective. We organize with Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB), a statewide coalition of over 60 organizations that seeks to “curb prison spending by reducing the number of people in prison and the number of prisons in the state.” During our formation as an abolitionist organization, we were skeptical about joining a group with non-profits. But we have consistently found that there is ongoing and powerful work being done to decarcerate that does not declare itself “abolitionist.” Working with an incredibly diverse group of (sometimes unexpected) allies has been central in building a unified and transformative movement against mass incarceration.

Earlier this year, we killed $4 billion of jail expansion money. And yet the number of those incarcerated in the state of California climbed higher. As we celebrate victories secured by a diverse and broad coalition, a unit that was unbowed in attempts to divide us over half-measures and empty promises, we also want to recognize the work we still need to do. Activist and academic Ruthie Gilmore has recently argued “the fact that prison numbers rose in 2013 is a testament to the deep fragmentation of social justice work in the USA.” Why is it that immediate struggles against criminalization are so often divorced from fights against deportations or from rebellions like those ongoing in Ferguson, Missouri?

In this November’s election California will consider Proposition 47, which decarcerates some inmates while accelerating more funding to cage “dangerous” offenders, taking away the possibility of parole for many. We know that state strategy has been to fragment our movement by offering “potential” victories at the cost of leaving the most marginalized and the most radical behind. We need to find a program – a target and plan for political development, from which we can connect our movements in a serious and ongoing way.

– Tash Nguyen and Courtney Hanson, Sin Barras

In the last issue, we introduced the history of “Dear Comrades,” a readers’ letters section inspired by pages from the Italian newspaper Lotta Continua. Grappling with a changing class composition, their organization solicited writings from an increasingly heterogeneous base of workers, making space for deeper political coordination across the class. Reviving that practice here, we present six more dispatches, each from a sectoral struggle with an immediate relationship to the state.

In the last issue, we introduced the history of “Dear Comrades,” a readers’ letters section inspired by pages from the Italian newspaper Lotta Continua. Grappling with a changing class composition, their organization solicited writings from an increasingly heterogeneous base of workers, making space for deeper political coordination across the class. Reviving that practice here, we present six more dispatches, each from a sectoral struggle with an immediate relationship to the state. Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine