Introduction

The paper “Against Noxiousness,” signed by the Political Committee of the Porto Marghera Workers, was presented 50 years ago, on February 28, 1971, at the Veneto Workers’ Congress in Mestre (Municipality of Venice, Italy). The Political Committee was an alliance between the local branches of two radical-left extra-parliamentary groups: Potere Operaio and il Manifesto. The paper, however, is best understood as part of the theory and praxis on noxiousness carried out by the Porto Marghera workerist group.

The Porto Marghera workerist group originated in the early 1960s through an encounter between intellectuals and students – mostly based in Padua and Venice – and militant workers disaffected with the line of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and its associated union, the Italian General Confederation of labor (CGIL).1 While the industrial area of Porto Marghera2 was an important setting for the early activism of theorists such as Antonio Negri, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, and Massimo Cacciari, the theories produced by the workers themselves have been largely forgotten. Yet this experience was remarkable because it involved workers employed by polluting industries denouncing in both words and deeds the environmental degradation caused by their companies from as early as 1968, when the workerists had a key influence in the local factories.

The Italian word nocività refers to the property of causing harm. Through its use by the labor movement, it came to encompass damage to both human and non-human life; hence it can be translated neither as “harm to (human) health” nor as “(non-human) environmental degradation.” It is rendered here literally as “noxiousness.” Struggles against noxiousness at Porto Marghera contradict the widespread belief that what is today known as working-class environmentalism did not have much significance in the labor unrest of Italy’s Long 1968.

The Porto Marghera group’s core was made up of blue-collar workers, although it also featured a significant presence of technicians and clerks, as well as activists external to the factories. Its stronghold was the major integrated petrochemical complex known as Petrolchimico, which employed some of its main leaders, including Franco Bellotto, Armando Penzo, and Italo Sbrogiò. The group’s theorizing around noxiousness was spearheaded by the Petrolchimico technician Augusto Finzi. Born in 1941 from a well-off Jewish family based in insular Venice, Finzi spent part of his early childhood in a refugee camp in Switzerland to escape the Shoah, in which the German chemical industry – the most advanced of the time – had played a key and dreadful role.

The group’s original contribution was based on the thesis of the inherent noxiousness of capitalist work and an antagonistic-transformative approach to capitalist technology. This led to the proposal of a counterpower able to determine “what, how, and how much to produce”3 on the basis of common needs, pointing to the utopian prospect of struggling for a different, anti-capitalist technology that would be compatible with the sustainable reproduction of life on the planet.

The group linked noxiousness to the workerist “strategy of refusal.” In this perspective, capitalist work is the production of value and thus the reproduction of a society of exploitation. Therefore, class struggle is not an affirmation of work as a positive value, but its negation. As Mario Tronti put it: “a working-class struggle against work, struggle of the worker against himself [sic] as worker, labor-power’s refusal to become labor.”4 The combination of the refusal of work with the dire health and safety conditions they experienced led the Porto Marghera group to the core idea that capitalist work is inherently noxious.

Gianni Sbrogiò, a member of the group, describes the context in which “Against Noxiousness” emerged as follows:

In September 1970, Potere Operaio’s Bologna Congress approved the proposal to combine with il Manifesto. In Marghera, this happened in December 1970 [with the creation of the Political Committee of the Porto Marghera Workers]. […] In mid-1971, the attempt to combine with il Manifesto ended, but our struggle to spend less time in the factories continued and, in April 1974, we autonomously won a daily worktime reduction of 1.5 hours in my factory’s most noxious units.5

“Against Noxiousness” represents an assessment of Italy’s Hot Autumn (1969–70) – a countrywide strike wave for the renewal of the national-sectoral collective agreements – and an early systematization of the group’s theory of noxiousness. At that time, they commended platforms centered on the principle of “more money, less work.” This strategy built on immediate working-class needs, seeking to expand them quantitatively to the breaking point of incompatibility with capitalism. Over the 1970s, however, the group would develop a reflection on how the quantitative reduction in worktime had to be supplemented by deep qualitative transformations of production to fully address noxiousness. The link between quantitative and qualitative demands is important, as workerists had criticized a mere focus on qualitative demands as being too liable to reformism and schemes of “co-management” in which representatives of the workers would be allowed to participate in the bosses’ latest schemes for increasing exploitation.

“Against Noxiousness” distinguishes between a noxiousness “traditionally understood” – i.e., consisting of tangible factors of toxicity and hazard – and an intangible noxiousness inherent to the capitalist organization of work, which makes the worker “an alienated entity, a piece of the productivist machine completely detached from the end of his work, subject to the continuous usury that brings upon him [sic] an inhuman use of his labor-power as it is the capitalist one, driven exclusively by the profits of the ruling class.” A struggle for health which targeted traditional noxiousness alone, like the one proposed by unions at the time through bipartite commissions tasked with reforming the work environment, was deemed insufficient because it would be harnessed towards the requirements of capitalist restructuring while leaving the crux of the matter – i.e., the priority of value production over life reproduction – untouched. This analysis can be read as a radical critique of green capitalism ante litteram.

The assessment on the role of unions and welfare reforms, however, appears as one-sided from today’s standpoint. Yet it should be understood in the context of the group’s positionality as an organization in direct competition with the unions in a time of massive assertiveness of working-class autonomy, and not taken as a dogma with a pretense to universality. In fact, the late 1960s saw the spread of workers’ rank-and-file committees across major industrial plants. This generated a dual leadership in which struggles from below pressured the unions to endorse the egalitarian demands of the base and negotiate for them at the institutional level.

The paper is also notable for identifying working-class communities as sites of class struggle at the point of reproduction: “The very working-class neighborhood […] is in sum a big cage where proletarians are locked up so that something more can be squeezed out of them. […] A blatant environmental noxiousness can be found there, engendered by the pollution of industrial smoke.” This was in line with the autonomist feminist analyses emerging at the time around unwaged reproductive labor. Another example of the extension of the struggle beyond the factories is the demand for free transport and for commuting time to be paid as worktime.

The Porto Marghera group’s theory of noxiousness could still inspire anti-capitalist environmentalist strategies in our pandemic and warming times, in which the impacts of capitalist noxiousness on life only grow increasingly stark. In fact, the pandemic can be seen as a global manifestation of the “jobs versus environment dilemma” and the related “job blackmail,” a situation in which workers are faced with a choice between defending their health and environment or keeping their jobs. As the subsistence of the working class is conditional on capitalist work, workers need jobs and thus endless economic growth to survive, no matter the health and environmental consequences. Therefore “job blackmail” is not a mere ideological falsehood, and it does not apply solely to large-scale, highly toxic industrial complexes. It holds a real sway across capitalist society and is intrinsic to it.

If reproductive needs – like the need for a healthy ecology – are the material basis of working-class environmentalism, the link between workers’ reproduction and capitalist work is the material basis of working-class denialism, and it must be broken. As the group writes below, capitalist noxiousness is a terrain of workers’ organization to be tackled with “political demands to unify the class, based on the common dependence on work.” The critique of capitalist work and technology, the combined demands for quantitative worktime reductions and qualitative changes in production, and the connection between workplace and community struggles theorized by the Porto Marghera workerist group can all be taken as live suggestions today in the global struggle against workers’ dependence on noxious capitalist work to live.

– Lorenzo Feltrin

1. The Struggle against Noxiousness

When facing the problem of noxiousness in the factory, it is necessary to immediately distinguish between one form of noxiousness – i.e., as it is traditionally understood – linked to the work environment (toxic substances, smokes, powders, noise, etc.), from the one linked more generally to the capitalist organization of work. No doubt, ultimately, the second type of noxiousness has a deeper impact on the worker’s psychophysical balance. It makes him [sic] an alienated entity, a piece of the productivist machine completely detached from the end of his work, subject to the continuous usury that brings upon him an inhuman use of his labor-power as it is the capitalist one, driven exclusively by the profits of the ruling class.

In this respect, we want to highlight the tendency according to which a reduction in traditional noxiousness is also in the direct interest of the capitalist class, on the one hand because it coincides with a necessary project of technological restructuring in a phase of accelerated capital concentration, and on the other hand to prevent a premature wearing down of the workforce, which in turn means increased social costs (pensions, social security, etc., in the framework of the integration of state and capital). In the new factory, coupled with a modest reduction in toxicities and thus in occupational diseases traditionally understood, there will be a strong increase in mental health disorders, with alterations of digestive, circulatory, and neurological processes engendered by the new form of intensive exploitation.

Work schedules, paces, shifts, craft subdivisions and all the other tools of the capitalist organization of work must therefore be attacked in a generalized struggle against noxiousness.

Indeed, the bosses can accommodate a struggle targeting exclusively traditional noxiousness through partial technical modifications (that are also functional to the capitalist factory’s imperatives of ceaseless technological renewal), but a broader struggle targeting the organization of work in its entirety will clash substantially against the capitalist interest. The last cycle of struggles shows that the working class has understood this and is adopting appropriate and unifying objectives. However, other forces are hiding behind the declaration (which on its own is just a declaration of principles) that noxiousness is intrinsic to the capitalist organization of work. To unmask them, an assessment of the struggles of the last two years is necessary.

Firstly, there is the union [CGIL] line on the health question that can be summarized as “monetization of noxiousness.” Here, certain noxious work conditions are compensated by the bosses through a specific item of the wage, from which all the different noxiousness allowances are derived. This union line deepens the “historical” line: an increase in the work provided, of which noxious conditions are part, a particular, more intense condition of labor-power provision (the workers can sell their labor-power for less time, but it is used up more rapidly), must be compensated with a higher remuneration. The link between work and the wage is maintained and even strengthened. Moreover, in the specific historical conditions in which the union promoted monetization, its line even protected the interest of single capitalists: i.e., the interest to “pay” for noxiousness at a time when a reform of the productive process, changing the machinery, would have been too costly or impossible.

In the last great cycle of struggles, the opposite watchword has powerfully emerged: the refusal of all monetization, “health is not for sale.” Such was the strength of this demand that it had to be incorporated also by the union, which has however twisted it. Because, to the union, the refusal of monetization means a platform that aims to negotiate, “reform,” and “recompose” the capitalist organization of work with a demand for the union to have a decisional role on the quantity and direction of investments. There are thus proposals to close the units with the highest toxic Maximum Allowable Concentrations (MACs).6 This boils down to the creation of bipartite commissions in which the “health technicians” come to an agreement, behind the workers’ backs, about what levels of “toxicity” will be tolerated at work. (In reality, they thus halt the workers’ struggle, removing the confrontation to yet another delegated instance. For example, in the factory Miralanza the bilateral commission was used to put down a very hard dispute.) Tendentially, as the union realized it was being constantly surpassed by workers’ spontaneism, it tried to go beyond the bilateral commissions, but only to deepen the link, or more precisely the subordination, of the workers to exploitation through the so-called “consensual validation,” that is, workers’ participation in the definition of acceptable conditions of exploitation (Turin union congress, November 1970). Finally, when the union demands wage increases linked to the value of work, is it not monetizing the noxiousness derived from the very sale of our labor-power to the bosses? Our struggle must strive instead towards toppling the system based on the exploitation of work.

We need to demand wage increases untied from productivity, as this is currently necessary to satisfy our needs.

This is the workers’ side of the refusal of monetization and it could be seen as implicit in the very early workers’ demand for monetization. When we used to demand money to compensate for noxiousness, the real meaning of our demand was not a trade between more work and higher wages (or, what amounts to the same thing, between more noxiousness and more money) but rather the untying of the wage from the logic of productivity as well as from specific noxious work conditions. It was a demand for a wage for its own sake, which stemmed from noxiousness in the same way as it could have arisen from the whole range of concrete work conditions. Even more clearly, in the refusal of monetization we can identify and focus the real objective of our struggle: the refusal of monetization becomes the refusal to bargain over the capitalist organization of work, the refusal of the capitalist organization of work in its entirety. Strategically, the right watchword that clearly emerges is: no to the negotiation of noxiousness. Noxiousness is non-negotiable just like the capitalist organization of work.

We need to work in this direction towards organizational levels able to give to the class the power to overcome the bargaining moment in order to directly reach the objective, to win against the bosses without leaving them room for maneuver between one battle and another. This also means that we must not contain the struggle within the factory, we need to extend it to the whole organization of society, which is the mirror of the organization of work. The struggle is not just against the capitalist factory, but against capitalist society. The worker exits the factory, where he experienced capitalist exploitation most directly, and returns to his neighborhood to immediately face again the alienation that he had endured in the workplace. The bosses have already taken his worktime, now they also use his free time by pushing him towards a consumerism completely estranged from real human needs, by exposing him to mass media pliant to the dominant interests, and in hundreds more ways. The very working-class neighborhood, as an urbanistic unit, is an expression of capitalist interests: it emerges alongside the establishment of large industrial centres, it serves real-estate speculation, it is in sum a big cage where proletarians are locked up so that something more can be squeezed out of them.

One of the many examples, a very recent one regarding the Mestre-Marghera area, is the neighborhood San Giuliano, built over a swamp in accordance to very concrete real estate interests. A blatant environmental noxiousness can be found there, engendered by the pollution of industrial smoke. San Giuliano is in fact located behind the industrial area and when the wind blows from the South all the shit emitted by the factories rains down on the neighborhood (those who have seen the green mud on the houses’ roofs know it full well). In Marghera the situation is even worse.

2. The Politics of Reform

The radicalism and egalitarianism of the platforms that emerged in the recent struggles mean, most importantly, that all aspects of the capitalist factory’s working conditions – i.e., all the aspects that, following the time-honored line of the traditional labor movement, are individually bargained over in a permanent negotiation that is however internal to the capitalist organization of work – are linked to the general and essential condition of the capitalist exploitation of work, and all objectives must be evaluated in this frame.

The link between a single “aspect” and a single demand must go: all objectives must be understood in relation to one demand and one horizon – thoroughly political, and altogether different – a demand for power.

It is here that our vision differs from the trade union one, as expressed by the “struggle for reforms.” We will deal in more detail with the reform of healthcare below. Now we want to highlight that, while developing their proposals for reforms, the union and the whole traditional labor movement must see the ever more repressive face of reformism: a capitalist attack on the working class and its autonomy. At the time when capital in Italy is in crisis due to rising workers’ insubordination in the factories, the union is trying to shift the terrain of struggle towards bogus reforms.

Clearly, the proposals for reforms and those for reigniting productivity gains are two sides, distinct but complementary, of the same political project. Lama7 and Berlinguer,8 Berlinguer and Colombo,9 are different sides of the same coin: productivity for reforms, say some, reforms for productivity, answer the others, together ensuring the link that is the condition for the bosses’ domination. For the sake of this, the union is even forwarding some capitalist interests. Here in Veneto, we all know what an obtuse tool of capitalist backwardness is the newspaper il Gazzettino.10 Well, it recently featured a number of interventions which recuperated some of the arguments on noxiousness developed by the movement (acknowledging how noxiousness is much broader and more diffused than the immediate dangers of the work environment, etc.), but this all serves to demonstrate that in the last instance the solution lies in a “preventive” medical science carried out by a new institution made of old people (technicians from previous bodies, consultants, trade unionists, etc.). The discourse of the bosses and the union clearly aims to rationalize some aspects of noxiousness: if workers’ struggles (but also capitalist imperatives) throw into crisis the old institutions of control, new ones must be devised.

3. A New Proletarian Organization

To correctly pose the question of noxiousness today (not just as a topic for discussion but as a practical initiative for immediate organizational purposes) means – as stated earlier – to articulate it in the last instance with the question of power. The only non-rhetorical way to solve this problem is to see it on the terrain of organization. In fact, we say that it is necessary to struggle against noxiousness insofar as it is “work-induced” noxiousness, which is why we demand shorter hours for all and not just for those working in hazardous units, wage increases, equality of statutory conditions, free transport, etc. These are understood as political demands to unify the class, based on the common dependence on work.

But all this would be meaningless if we were unable to stabilize a real organizational level in relation to and within this struggle, because without it there would be no perspective for workers’ power, a communist power in the hands of the working class, as the only material remedy to suppress work-induced noxiousness, to plan the elimination of the source itself of all noxiousness and workers’ misery, to eliminate the exploitation of work. It is thus necessary, in framing agitation and struggles related to noxiousness, to develop organizational levels with the capacity to progressively win partial struggles and, more generally, to be the organizational expression of the current level of political class consciousness. In Porto Marghera too, it is crucial to build a Workers’ Political Committee that, by aggregating vanguard elements among the workers, will function as a catalyst-leader of struggles, in their necessary political dimension.

We have uncovered earlier the complementarity between reforms and relaunch of productivity. We have seen how this project has been managed over the last months in the factories and in society. But we have also witnessed its failure, too bad for all reformists. Since the Hot Autumn, a constant struggle has managed to keep reforms and productivity separated and to defeat both, the first with the most total indifference (the outcome of the last strike for reforms, also in Marghera, shows this clearly), the second with a generalized continuity of workers’ and proletarian initiative that nobody believed to be possible after last years’ great wave. Reforms and productivity cannot be kept separate for long: the current political crisis is there for everyone to see. Working-class initiative deserves credit for it, but we cannot be satisfied yet. The very deepening of the crisis will not be materially possible if the objectives and political questions that the history of struggles itself has powerfully revealed are not made more explicit, communicated, and radicalized in the whole, broad front of the struggle, if there is no political quality to the struggles, quality that only the broadening and strengthening of organization can guarantee. This, to us and to all the factory and movement vanguards, is now the decisive terrain.

4. The Reform of Healthcare

What are the most significant proposals for the struggle against noxiousness put forward by the union and the PCI? The party pushes for healthcare reform. The union tries to lead the factory struggle and adds demands such as shorter hours for “noxious” shifts and units only (e.g., Petrolchimico), the reduction of MACs, the closure of those units where MACs cannot be reduced, etc.11

Do these objectives fit into a strategic line that sees the struggle against noxiousness as a struggle against the capitalist organization of work? Not at all! It is pure mystification to pose the Local Health Units as an instrument capable, through “democratic” management, of getting us away from the current delegation to doctors of all responsibility for protecting the health of the proletariat. This merely shifts the responsibility from the factory and mutual fund doctors to the Local Health Unit doctors: the shift is from a healthcare system directly managed by the capitalists to a system managed by the state, which is no less capitalist. In the new healthcare system, the union only will co-manage health with the bosses.

To propose that the Local Health Units be managed by the city councils as a solution to the problem of prevention (“by managing hospital and specialist health assistance, the city councils will begin to remake notions of prevention and therapy,” PCI law proposal) is a pure mystification. The city council, as an institution of capitalist society, will merely be able to mediate capitalist interests, reaching in the best-case scenario earlier therapies and a reduction of MACs in the factories. As long as the bosses are around, they will be the ones holding the reins of power and there will be no real prevention.

Prevention means overthrowing the capitalist organization of work from the bottom up: to think that the city councils and the Local Health Units will be able to wage such a struggle is simply ridiculous. We have already begun doing real prevention by staying home from work when we wish. Work itself is noxious and rates of absenteeism show that we have understood this (12% at FIAT and up to 24% at Mirafiori, 13.6% at Olivetti, 8.8% at Alfa Romeo, etc.).

Tackling the problem of the right to health, as proposed with the Local Health Units, means advancing the capitalist logic of scientific sectoralism, i.e., the defense of health is the duty of medical science. But we know that the defense of health is chiefly a political struggle that must be fought by the proletariat directly. With its reformist politics, the PCI – and the union in the factory on its behalf – tends to take a fertile terrain of struggle like that of noxiousness and displace it outside of the factory, delegating health management to the institutions (local administrations and parliament), and taking away from the proletariat the direct organization of the confrontation. The reform of healthcare is a moment of rationalization which the capitalists themselves need – as the current hospitals and mutual funds are no longer fit for the purpose of controlling the working class – in order to channel those workers who had left due to illness back into the labor process.

To the working class, this healthcare reform will involve increases in medical support at best, but it certainly will not be a step towards the conquest of power as the PCI claims.

5. Articulating the Struggle in the Factories

Working Hours

The first objective in the struggle against noxiousness in the factories is the shortening of working hours: the less we work, the less we are exposed to noxious work. While the union proposes 36 hours for the shift workers and those working in hazardous units – considering once again noxiousness as a problem concerning exclusively those who work in an environment particularly polluted, noisy, etc. – we respond that noxiousness impacts all workers through work itself and thus 36 hours is a correct objective for all.

It is also convenient for the bosses to consider noxiousness in the purely traditional sense. They can resolve the problem by moving the worker away from one hazardous unit to another for a few hours a day. First of all, as we have already noted, this does not eliminate the noxiousness inherent to the capitalist organization of work. Moreover, this is not even an effective way to combat traditional noxiousness because it leads to a greater number of workers being exposed to a toxic environment given their rotation between different units.

Pay Grades

Internal mobility, additionally, is a weapon in the bosses’ hands to introduce pay grades linked to one’s professional career. Precisely when the old pay grade criteria are being shaken by workers’ struggles,12 the bosses are looking for new ways to divide the class, and the union proposal to rotate work positions is handy in this respect.

We must respond with a struggle aiming to reach one pay grade equal for all, blue- and white-collar workers, to build class unity where the bosses want division.

Overtime

Struggling for shorter working hours means demanding the abolition of all overtime, refusing blackmail based on low wages. Wages lost [from overtime] must be compensated for through an increase in the base wage rate.

Transport

When we talk about working hours, we must understand them to include the time necessary to travel from home to the factory: this is time we spend for the bosses and they must pay for it!

The Pace of Work

We know very well that any victory on the side of working hours can be offset with an intensification of the pace of work. Therefore, we must attack the bosses on this issue also, but not in the sense of agreeing to certain paces through bipartite commissions, helping the bosses to exploit us more rationally. We must constantly oppose the paces that the bosses impose on us, finding in the struggle new moments of unity and organization.

Shifts

The same goes for shifts. Night shifts undermine the workers’ psychophysical balance, constantly modifying those biological rhythms that should be kept regular. The shift system is thus a quintessential manifestation of the noxiousness of the capitalist organization of work and night shifts must be abolished. To those who claim this is impossible due to the imperatives of continuous production, we respond that continuous production is a capitalist invention and therefore this is not our problem. A new system can be invented! To beat the bosses on this point, crucial for the functioning of their factories, we must build an adequate organization. The outcome of any clash with the bosses depends on the balance of power, which to the proletariat means combativity and an organization that can support such combativity.

Environmental Noxiousness

In the struggle against noxiousness we must not forget environmental noxiousness, which we feel daily through chronic bronchitis, deafness, and worse diseases. But we must not get bogged down in the logic of bargaining over MACs. This is also because MACs are one of the biggest lies in the domain of science. Acceptable concentrations vary widely depending on the instruments used, the methodology, and the researcher’s theories. But, in the end, it is always the workers who fall ill. Even if an acceptable MAC were correctly established (but they should come and explain to us how this is even possible for carcinogenic substances), there are individual variations: one worker can suffer much more than another from exposure to the same concentration of toxic substances. Therefore, if anything, the analysis should be centred on the workers rather than on the work environment. If one single worker is harmed by the work environment, the latter must be considered noxious.

Any specific struggle over environmental noxiousness is meaningful only if it is connected to a wider battle against the noxiousness of the capitalist organization of work. In this way, if we are able to express high levels of combativity when tackling noxiousness, the bosses themselves will try to reduce noxiousness through partial technical modifications. Through the just struggle against the capitalist organization of the factory we will also win the technical ameliorations we need in the work environment.

6. Extension of the Struggle to the Community

Tackling the problem of the extension of the struggle against noxiousness to the community, we must beware of two possible errors:

1) The mistake of separating the community struggle from the factory struggle, reducing it to a “democratic struggle,”13 an initiative which addresses all sectors of society and improves the current situation, though ultimately only rationalizing capitalist society itself. The popular struggle14 has a subversive meaning only if it is directed by the proletariat. In this sense, we must reject once again the PCI and trade-union approach to the struggle for social reforms, in which the figure of the worker doubles over and over again – as a citizen, a parent, etc. – with the struggle in society taking place alongside the factory struggle rather than being fused with it.

2) We must also avoid the opposite danger, of seeing the community struggle as a mere appendage of the factory struggle, itself limited to mechanically conveying factory-based objectives to the outside. We must instead highlight the unifying moments of both types of intervention, within the same strategy of political organization, finding specific objectives upon which the community struggles must converge. In Porto Marghera and the nearby areas, we must now begin to agitate and raise the question of noxiousness correctly.

Defending our health means struggling against the noxiousness intrinsic to the capitalist way of life.

–Translated by Lorenzo Feltrin

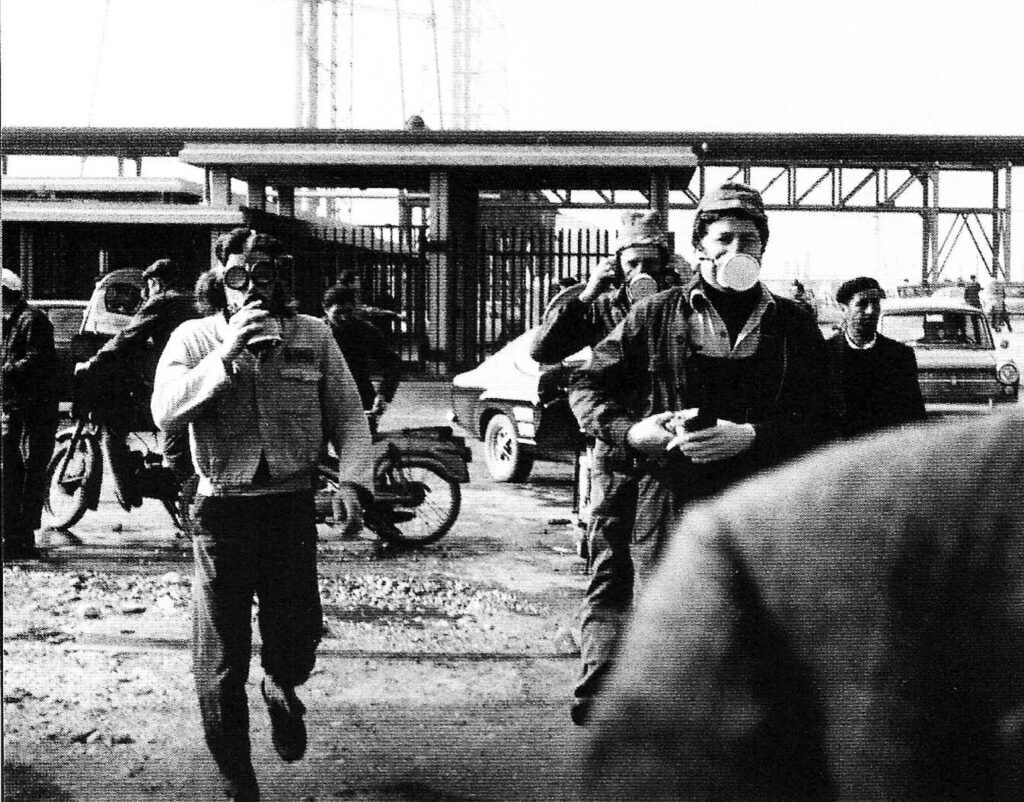

For the images above and further resources on the Porto Marghera workers’ struggle, see Luciano Mazzolin’s Porto Marghera Archivio Ambiente Venezia.

References

| ↑1 | Devi Sacchetto & Gianni Sbrogiò, eds., Quando il potere è operaio: Autonomia e soggettività politica a Porto Marghera, 1960–1980 (Rome: Manifestolibri, 2009). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Cesco Chinello, Storia di uno sviluppo capitalistico: Porto Marghera e Venezia 1951–1973 (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1975). |

| ↑3 | The Porto Marghera workerist group put forward this slogan in the late 1970s and it appears in several articles and leaflets. An article that explains it can be found in Controlavoro (March 19, 1979): 1. |

| ↑4 | Mario Tronti, Workers and Capital, trans. David Broder (London: Verso, 2019 [1966]), 273 (translation modified). |

| ↑5 | E-mail communication with the author, March 16, 2021. |

| ↑6 | Translator’s Note (TN): The maximum concentration in air of a toxic substance that the relevant authorities are willing to tolerate. |

| ↑7 | TN: Luciano Lama (1921–1996) was a CGIL trade unionist and PCI politician. He was CGIL’s national secretary general between 1970 and 1986. |

| ↑8 | TN: Enrico Berlinguer (1922–1984) was PCI’s national secretary general between 1972 and 1984. |

| ↑9 | TN: Emilio Colombo (1920–2013) was a Christian Democracy politician and Italy’s PM between 1970 and 1972. |

| ↑10 | TN: Il Gazzettino is Venice’s main local newspaper, and at the time it was politically close to Christian Democracy. |

| ↑11 | TN: Under the supervision of former fascist officials, the “production inferno” of Porto Marghera’s post-WWII decades featured appalling toxicities and hazards, where exposure to heat, smoke, and powders and the lack of health and safety measures resulted in widespread accidents and occupational diseases such as cancer, silicosis, asbestosis, hepatic and dermatological pathologies, etc. See Gilda Zazzara, Il Petrolchimico (Padua: Il Poligrafo, 2009). |

| ↑12 | TN: The workerist perspective was centered on the knowledge of the productive cycle and radically egalitarian demands as an instrument for class recomposition: equal wage increases (in absolute value) for everyone or inversely proportional wage hikes, a guaranteed minimum wage for all workers, the reduction of the working week, and an abolition of differences in statutory conditions (holidays, social contributions, etc.) among the different categories of employees. |

| ↑13 | TN: Here the Workers’ Committee is likely targeting the official line of the PCI at the time, which was to prioritize the defense of parliamentary democracy and advocate for reforms that would benefit the whole of Italian society rather than workers in particular. |

| ↑14 | TN: By “popular struggle” the authors are referring to a struggle that goes beyond the working class to accommodate other segments of society, particularly the traditional middle class. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine