I spend a lot of time thinking about Pete Seeger. I was even thinking of him the night news of his death flashed on my screen. In the course of working on an excruciatingly long-term film project on the politics of country music, the influence of Pete Seeger arises quite often. Part of the thesis of the film, called Open Country, is that Pete Seeger should be considered a founder of country music. Not folk music, mind you, as that has been around for some time. Country music. Nashville, I believe, owes Pete a statue in the center of town. But I will return to this seemingly absurd point later.

It is not possible to sum up the contributions of Pete Seeger in this commentary, nor in any article, anthology or book. His connection to the labor rebellions of the Great Depression and the post-War years, battles with HUAC and the anti-communist witch-hunts, participation in the Civil Rights movement in the South, agitation against the wars in Vietnam, Central America, and the Middle East, building a community effort to clean industrial waterways, acting against global warming—these are all rich areas where Pete Seeger would have to be included. To do justice to the legacy of Pete Seeger, indeed, one would have to write about every significant movement for social justice in the United States, if not the world, within the last 80 years.

With his passing, as I try to take the long view of his life, I am tainted not by what I know from books, recordings and word-of-mouth legacy, but by the small personal experiences I had of him. Growing up in the 1960s, I had heard a few songs of his in school, sung “Where Have all the Flowers Gone” in summer camp and saw him as a distant dot on a stage at anti-war rallies. Our family watched the Smothers Brothers television show religiously, and was vaguely aware of his censorship battle while “waist deep in the big muddy.” But in my transition from pro-war patriotic teenager, to peacenik, to militant revolutionary, Seeger was too much “kumbaya” and not enough “street fightin’ man.” It wasn’t until the mid seventies, as I transitioned into a life in factory jobs and labor activism, that I realized how profound Seeger’s contributions were. I discovered “Talking Union,” a record album of the Seeger-led Almanac Singers, with the labor songs that sitdown strikers and factory-occupying industrial workers sang across America in the 1930s and 1940s. They called themselves the Almanacs after Lee Hays remarked that “back home in Arkansas farmers had only two books in their houses: the Bible, to guide and prepare them for life in the next world, and the Almanac, to tell them about conditions in this one.” I was surprised that I knew many of these songs from the Civil Rights movement, and discovered that they were indeed transported by Seeger and others from Flint and Pittsburg to Selma and Montgomery. Pete believed singing gave people the strength and resolve to maintain courage and dignity in the face of clubs, mace, jail and violence. “Like a tree standing by the water” was relevant wherever your fight. Throughout his life, he brought music to every arena of popular struggle. He believed in the power of music. He also believed deeply in the power of individuals to rise above their daily lives and join in a struggle for the greater good. Quite simply, he believed in two facets of society no longer mentioned in polite company. He believed in “the masses” and he also believed in “the working class.”

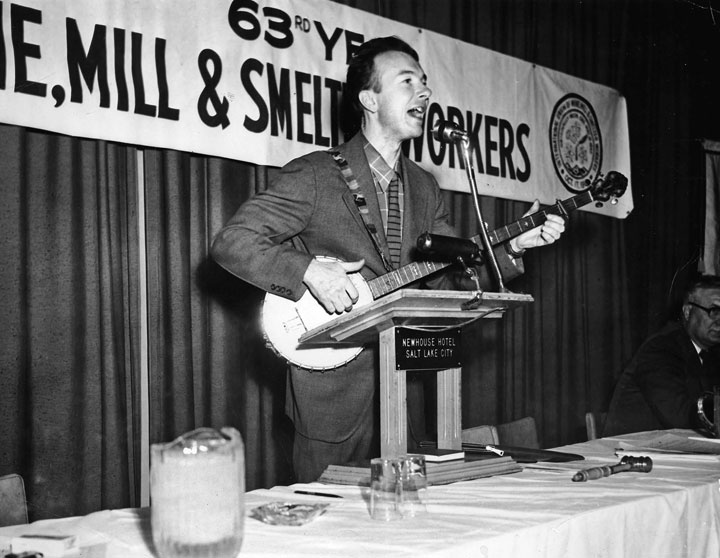

In the late seventies, a friend of mine whose father had fought in Spain invited me to a reunion of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. We entered the dark, wooden lodge-like old union hall in the East Bay of San Francisco, to encounter perhaps 50 older, somewhat grizzled men sitting on folding chairs around tables. Sitting casually amongst them was a tall, slim Pete Seeger, plucking a banjo, and chatting amiably with his table of military veterans, those who chose to fight prematurely against fascism. No generals, politicians or Chamber of Commerce people to thank these veterans for their service, just Pete Seeger, who stood later during the evening and roused them with the songs of their militant youth.

Years later, while on a visit to the squatted community gardens of the “Loisaida,” the remnants of a once working-class and Nuyorican Alphabet City on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, I spied the man ahead of me walking with an instrument case. As I approached from behind, I could see it was not a guitar, but a banjo. The man turned into a small pocket park, and shortly ahead was a group of perhaps 25 school children, sitting in the park in a semi-circle. It was Pete Seeger, of course, who serenaded the kids of the neighborhood with children’s songs. I spoke with him after his casual performance, sitting in a wooden gazebo in the park, while he packed up his banjo. “I try to get out here as often as I can, to play for the children, and to visit the neighborhood.” He left unaccompanied, on foot, just an old man and a banjo.

Years later I found myself beginning research on the politics and history of country music, which I believe is rightfully the progressive voice of the rural and working poor, not the right wing, cowboy hat, pickup truck listeners of Nashville pop. Preparing to examine the long history of country music, I was stopped short in the late 1940s-early 1950s. That was pretty much as far back as music called “country” went. Before that, it was called “folk.” All the music we would call “country” today was listed on the charts as “folk.” Hank Williams, the standard by which every self-respecting country musician holds themselves (What would Hank do?) considered himself a folk musician. Country music only showed up in the midst of the McCarthyite and HUAC assault on popular culture, whose impact is widely known on the film industry, somewhat known on the television and radio industry, but fairly unexamined in the music industry. As Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, the Weavers and others who would dare sing about the struggles of poor and working people were dragged before HUAC and other un-American investigative committees, the industry read the lyrics on the wall. Their self-preservation stance was: We don’t do “folk” music, we do “country” music: God, guns and beer, not coal miners, sharecroppers and strikers. Almost overnight, the industry charts and lists separated “folk” from “country,” with Nashville as the homeland of country. Folk music with suspect lyrics were marginalized and pulled from the air, while the now safe country music hit the charts. So, country music—that’s Pete’s fault.

As I spent more time on research into country music, I kept being dragged back to folk music, and to the role of Pete Seeger. For the film, I dreamed of interviewing him. But how? After months of asking around, all I could come up with was a PO Box in upstate NY. But he did not know who I was, or anything about my intentions. Why would he speak with the likes of me? One night I wrote him a letter and sent it off to the PO Box, not expecting any response. No response came and I quickly wrote off the possibility. Then, nine months later I had a voicemail. “This is Pete Seeger, finally got around to opening your letter. Looks like an interesting project. Why don’t you give me a call and we’ll set something up.” Then he left his phone number. I immediately called back and booked a plane for NY.

Picking up a friend and his daughter for technical support, we drove from Brooklyn up to his house in upstate NY in sub-zero weather, negotiating around dirt roads and frozen landscape. We approached a complex of cabins at the top of a hill, not knowing if we’ve reached our destination or not, when we saw an elderly man with a knit cap splitting wood on the side of the house. Pete, of course. He invited us into his house, where his wife Toshi insisted that Pete “build that fire higher, as it’s freezing in here,” so our crew pitched in splitting and carrying wood to get the house warmer. We got to roll camera and talk for hours, about country music, traditional music, revolutionary change. We heard the great stories about writing “Union Maids” with Woody Guthrie in the back room of a union hall in Oklahoma, about sharing “We Shall Overcome” with SNCC and other civil rights activists, about his involvement in organizing a community push to clean up the Hudson, about his optimism for the future.

It struck me in the months afterwards that Pete Seeger embodied two of the most important characteristics I value in a revolutionary. He truly believed in the power of ordinary people to act for social change on a mass level. Many today give lip service to that idea, but Pete really believed it. And why not? In his lifetime he was witness to rank-and-file workers standing together and occupying their factory, of communities sitting in and standing up to brutally racist attacks, of students who put down their books and took over administration buildings, of young people who blocked trains of munitions heading for war, of thousands of young and old who occupied Wall Street. He’s advocated for “the little drops that add up to buckets, that become a tidal wave of change.” And he sang for them all. The other valuable attribute I found in him: his political ideas were lived in his daily life. His generosity and respect to individuals was genuine, not rhetorical. While interviewing him, I found there was a major film crew from Europe coming by the next day. Yet, it was clear my little production was as important to him as that production was. He remarked that just a few days before, “that fellow Bruce Springsteen” was sitting in the same chair, asking him similar questions. I still had the impression that my sitting there was just as important to him. Pete lived the politics he believed in, he built his own house, grew a garden, chopped his own wood, was kind to people, and yet on top of it all still managed to change the world. And in the true tradition of punk rock, “he booked his own damn life” although he may have been many months behind!

In the weeks to come, there will be many eulogies to Pete Seeger. Many will downplay and sanitize who he was, stripping his politics away and leaving a kindly man who played banjo songs about America. Others will question and poison his motives, bringing in the spectre of the Communist Party, USA and when he broke from its Stalinist past. One thing is for sure. A profound link with the long trajectory of revolutionary change in the US has been lost. Someone who understood the links between labor, race, ecology, peace, culture and music. One who understood the importance of bringing masses of people into the struggle, to be respectful, inclusive and inviting. These are all qualities we are in desperate need of today. May his passing inspire the ranks of many new Pete Seegers.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine