The following is an extended version of Geoff Eley’s presentation at the annual Kaplan Memorial Lecture at the University of Pennsylvania on March 26, 2014. The theme of the panel was “What’s Up with the New History of Capitalism?”

Where does the new interest in the “history of capitalism” come from? I’d suggest the following rudiments of an answer. The financial crisis of 2008-09 has clearly placed certain issues of historicization on the agenda. If the accelerated and seemingly unstoppable drive for the “flattening” of the world through a process of neoliberal globalization since the early 1990s has not actually brought us to a permanently unfolding and self-reproducing neoliberal present, but has rather encountered severe structural problems, then how do we historicize this current time? That is, how do we understand the contemporary crisis of capitalism, in all its political and social ramifications, in relation to longer-run processes of capitalist restructuring and their logics of development and difficulty; and how do we locate the history of the present inside a larger-scale framework of periods and conjunctures?

One important historiographical shift that’s relevant here is the playing out and running down of the culture wars of the later 1980s and 1990s. My own interventions in that regard have argued for recuperating some important grounds of social history without disavowing the vital gains accomplished in the course of the cultural turn. My own mantra has been “No Need to Choose!” 1 This rather belies the narrative presented in the New York Times article that announced the new popularity of the history of capitalism. In fact, setting “history from below” against histories of “the bosses, bankers and brokers who run the economy” is to invoke a false antinomy.

It’s open to question, in any case, whether we’ve actually had “decades” in which scholarship has been dominated by studies “focusing on women, minorities, and other marginalized people seizing their destiny,” leaving entirely aside for the moment whether it’s fruitful to study the workings of capitalism by focusing in the first instance on discrete categories of actors in the manner the NYT implies, whether businessmen or employees. This will also vary hugely context by context. In the German field, for example, neither the social history wave nor the turning to cultural history entailed remotely any neglect of industrialists, financiers, landowners, bureaucrats, judges, the professions, or any other category among the dominant classes.

Once we start looking closely at the implications of the NYT claim, especially in relation to the actual content and distribution of historical research and publication during the past several decades, in other words, we’ll see just how primitive its understanding turns out to be. Just to use its own terms for the moment, “history from below” has rarely meant some discrete and exclusive empirical focus “on women, minorities and other marginalized people seizing their destiny.” Rather, those interests and commitments have long been abstracted into a set of conceptual rules and protocols, methodologies and theoretical approaches, topics and fields, cautions and incitements, that allow the largest of analytical questions to be brought down to the ground, including all those concerned with the history of capitalism. In my own field of German history, I’d begin a demonstration of this claim with Alltagsgeschichte (history of the everyday) and the cumulative accomplishments of microhistory and its everyday analytic. More generally, Walter Johnson’s work seems to be an excellent illustration, whether in his two monographs or in the various interpretive writings. 2

I also want to mention that the Occupy Movement and the widening extremes of social inequality inside most capitalist societies are certainly having significant effects on how historians are thinking, which we can expect to find materializing in projects and debates in about five or six years time. There are already some fascinating outcomes being registered, such as Peter Linebaugh’s new book, for example, Stop, Thief! The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance (Oakland: PM Press, 2014). But for the purposes of this talk I’m confining myself to the following twin phenomena – the new bases of working-class formation under the neoliberal transformations of the past three to four decades, together with the fresh forms of political mobilization these are beginning to produce – as symptoms of the profoundly far-reaching capitalist restructuring that got properly under way during the 1980s.

To bring the specificities of the present into focus, I’ll argue that the preceding era, essentially the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, often treated as a ground from which a successful politics of the Left might be rebuilt, was actually a very particular and non-repeatable time. In doing this, I’ll draw on two bodies of argument. One uses the increasingly rich historiography of slavery, post-emancipation societies, and the Black Atlantic, with its challenge to our basic notations of the origins of the modern world. The other concerns the distinctive conditions of accumulation and exploitation now defining the new globalized division of labor of the present, particularly in the deregulated migrant and transnationalized labor markets still being generated at ever-accelerating pace. In this second argument I’ll draw some contrasts with the previous accumulation regime established after 1945 and lasting until the mid-1970s.

So far, interestingly, much of the “Black Atlantic” argument has tended to concentrate around questions of citizenship and personhood arising from the French Revolution, most classically via the Haitian Revolution and the wider insurrectionary radicalisms in the Caribbean, rather than around the modernity of capitalism per se. 3 Moreover, treatments of the societal transformations accompanying the end of New World slavery tend to stress the countervailing logic of securing the new norm of the free labor contract, which worked inexorably against the longed-for ideals of civic liberty and emancipated personhood. The conceptual focus tends to prioritize the new relations required by the capitalist labor contract, even as elaborate machineries for deployment of indentured and “semi-free” labor power continued to persist, so that the promised meanings of freedom and citizenship, which were in any case vitally conditioned by race and labor during the transition out of slavery, necessarily became compromised. But the already formed contribution of slavery per se to a capitalist system of production tends not to be brought quite as easily into thought. Slavery’s classic notation as an essentially pre-capitalist formation, or at best an anomaly once “the wage labor-driven capitalist system [began] maturing on a global scale,” remains tacitly intact. 4

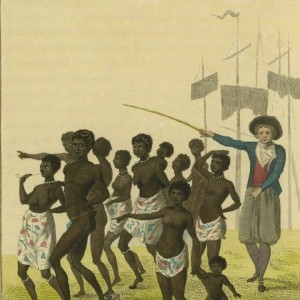

But in the slave economies of the Caribbean, slavery was not some archaic or pre-capitalist social formation in anomalous relationship to the rise of capitalism, but on the contrary produced the first modern proletariat of large-scale, highly organized, and integrated capitalist production. 5 Situating the New World plantation economies inside capitalist regimes of production, exploitation, and accumulation vitally destabilizes our more familiar teleologies of capitalist industrialization. It rethinks working-class formation through a set of social relations that both preceded and starkly differed from those normally attributed to capitalist industry. Organized on the most global of scales, the labor regime in question continued to overlap and coexist with that of capitalist industry well into the epoch of the Industrial Revolution classically understood. To the modernity of the enslaved mass worker, moreover, we can add the analogous importance of domestic servitude for the overall labor markets and regimes of accumulation prevailing inside the eighteenth-century Anglo-Scottish national economy at home. 6 If we then put these two social regimes of labor together, that of the enslaved mass worker of the New World and that of the servile laborers of the households, workshops, and farms of the Old, then we have the makings of a radically different account of the dynamics of the rise of capitalism and the modes of social subordination that enabled it to occur. In the most basic of social-historical terms, for example, servants in their many guises formed one of the largest and most essential working categories of the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (precisely at the core of industrialization), yet seldom plays any role in accounts of either the capitalist economy or working-class formation. So if we take seriously on board this centrality of non-industrial work along with service, domestic labor, and everything that’s accomplished in households, while adding it to the engine of enslaved mass production, then our perspective on political economy and working-class formation will surely have to change. 7

The same can be said once we consider the distinctiveness of capitalism in the present. By rethinking the early histories of capital accumulation via the generative centrality of slavery and servitude, we’re already querying the presumed centrality of waged work in manufacturing, extractive, and associated industry for the overall narrative of the rise of capitalism. That shifting of the perspective relativizes wage labor’s place in the social histories of working-class formation and opens them to other regimes of labor. By that logic, waged work’s claim to analytical precedence in capitalism’s developmental history no longer seems secure. Indeed, the de-skilling, de-unionizing, de-benefiting, and de-nationalizing of labor via the processes of metropolitan deindustrialization and transnationalized capitalist restructuring in our own time have also been undermining that claim from the vantage-point of the present. Today the social relations of work have been drastically transformed in the direction of the new low-wage, semi-legal, and deregulated labor markets of a mainly service-based economy increasingly organized in complex transnational ways. In light of that radical re-proletarianizing of labor under today’s advanced capitalism, I want to argue, the preceding prevalence of socially valued forms of organized labor established after 1945, which postwar social democrats hoped so confidently could become normative, re-emerges as an extremely unusual and transitory phenomenon. The life of that recently defeated redistributive social democratic vision of the humanizing of capitalism becomes revealed as an extremely finite and exceptional project, indeed as one that was mainly confined to the period between the postwar settlement after 1945 and its long and painful dismantling after the mid-1970s.

In light of that contemporary re-proletarianizing of labor, perhaps we should even see the period in which labor became both collectively organized and socially valued – via trade unions, public policy, wider common sense, and the acceptable ethics of a society’s shared collective life – as merely a brief blip in the history of capitalist social formations whose ordering principles have otherwise been quite differently institutionalized and understood, whether at the beginning (in the eighteenth century) or at the end (now). As I’ve just suggested, the blip in question may be located historically inside Eric Hobsbawm’s “golden age” of the unprecedented post-1945 capitalist boom whose forms of socio-political democratization (through planning, full employment, social services, redistributive taxation, recognition for trade unions, public schooling, collectivist ideals of social improvement, a general ethic of public goods) were brought steadily under brutally effective political attack after the mid-1970s. 8 At most, one might argue, the labor movement’s rise and political validation may be dated to the first three quarters of the twentieth century, varying markedly country by country.

Thus, the classic wage-earning proletariat actually re-emerges in this perspective as a relatively transitory and sectorally specific formation produced in quite delimited historical periods and circumstances. Moreover, under any particular capitalism wage labor has in any case always continued to coexist with various types of unfree and coercive labor. Those simultaneities – of the temporal coexistence inside a particular capitalist social formation of forced, indentured, enslaved, and unfree forms of work with the free wage relationship strictly understood – need to be carefully acknowledged. They become all the more salient once we treat capital accumulation on a properly global scale by integrating the forms of surplus extraction occurring in the colonial, neocolonial, or underdeveloped worlds. The West’s privileged prosperity, including precisely the possibility of the social democratic improvements associated with the three decades after 1945, has been founded, constitutively, on horrendous repertoires of extraction and exploitation on such a world scale. Other forms of labor coercion have likewise been characteristic of even the most advanced capitalist economies in their time, as for instance during the two World Wars, or under the racialized New Order of the Third Reich. In these terms, I’d argue, the search for a “pure” working-class formation, from which forms of enslavement, servitude, indenturing, impressment, conscription, imprisonment, and coercion have been purged, remains a chimera. Once we define working-class formation not by the creation of the wage relationship in the strict sense alone, therefore, but by labor’s contributions to the wider variety of accumulation regimes we can encounter in the histories of capitalism between the eighteenth century and now, we can see the multiplicity of possible labor regimes more easily too.

By focusing on eighteenth-century servants and slaves, those two largest categories of laborers during earliest capital accumulation, we’re able to see the extremely varied labor regimes that sustained those processes, including those based on coercion. In some ways this argument has affinities with earlier critiques of the classical narratives of the Industrial Revolution, which emphasized instead proto-industrialization, small-scale rural industry, new forms of non-industrial manufacturing, and the wide range of “alternatives to mass production.” 9 Clearly we need to hold onto the necessary distinctions between forms of “free” and “coercive” labor, because otherwise certain specificities of the labor contract under industrial capitalism would become much harder to see, particularly those that require new domains of power and exploitation beyond the immediate labor process and the workplace per se.

To summarize: on the one hand, there are strong grounds for seeing servitude and slavery as the social forms of labor that were foundational to the capitalist modernity forged during the eighteenth century; and on the other hand, there is equally compelling evidence since the late twentieth century of the shaping of a new and radically stripped-down version of the labor contract. These new forms of the exploitation of labor have been accumulating around the growing prevalence of minimum-wage, dequalified and deskilled, disorganized and deregulated, semi-legal and migrant labor markets, in which workers are systemically stripped of most forms of security and organized protections. This is what is characteristic for the circulation of labor power in the globalized and post-Fordist economies of the late capitalist world, and this is where I think we should begin the task of specifying the distinctiveness of the present. Whether from the standpoint of the “future” of capitalism or from the standpoint of its “origins,” the more classical understanding of capitalism and its social formations as being centered around industrial production in manufacturing begins to seem like an incredibly partial and potentially distortive one, a phase to be found overwhelmingly in the West, in ways that presupposed precisely its absence from the rest of the world and lasted for a remarkably brief slice of historical time. 10

Finally, in light of all of this, we badly need work – conceptually, historiographically – that can help define the specificities of working-class formation in our new early twenty-first-century present, not just in terms of its materialist sociologies and logics of structural coalescence, but also in terms of its forms of collective consciousness and collective agency. In some ways the global scale of the new brute materialities of work, labor, and working-class formation have been relatively easy to grasp – in terms of the global redistribution of heavy industry, all kinds of manufacturing, and factory assembly to wherever labor costs, tax regimes, environmental regulations, labor law, health and safety oversight, policing, territorial sovereignties, and public governance are most conducive; in terms of the transnationalizing of labor markets across regional, continental, and truly vast geographies of distance; in terms of a deregulated financial sector, whose dominance is severed from any apparent mechanisms of accountability or relationship to productive investment; in terms of a contemporary regime of accumulation ordered around the untrammeled mobility of capital, the spectacle of consumption, and the gutting of public goods. In all of these terms we are able to grasp the contemporary sociologies of class formation, assisted by the writings of people like David Harvey, Tim Mitchell, Göran Therborn, Pietro Basso, Guy Standing, Marcel van der Linden, Beverly Silver, and Leo Panitch. 11 But what is still very hard to see is the kind of politics that might produce coherence and organized agency under these new conditions of global accumulation, a politics that might enable democratic capacities with efficacies comparable to those attained by the socialist tradition earlier in the twentieth century. In these most fundamental of transitive terms, how should we think about the politics of working-class formation today? I’m sure that in the coming few years we’ll begin to see important efforts to answer that question.

References

| ↑1 | “Dilemmas and Challenges of Social History since the 1960s: What Comes after the Cultural Turn?”, South African Historical Journal, 60/3 (2008), 310-33; “No Need to Choose: Cultural History and the History of Society,” in Belinda Davis, Thomas Lindenberger, and Michael Wildt (eds.), Alltag, Erfahrung, Eigensinn. Historisch-anthropologische Erkundungen (Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2008), 61-73. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999); “On Agency,” Journal of Social History, 37:1 (2003), 113-24; “Inconsistency, Contradiction, and Complete Confusion: The Everyday Life of the Law of Slavery,” Law and Social Inquiry, 22:2 (1997), 405-33; also Jean-Christophe Agnew, “Capitalism, Culture, and Catastrophe,” in James W. Cook, Lawrence B. Glickman, and Michael O’Malley (eds.), The Cultural Turn in U.S. History: Past, Present, and Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 401-05. |

| ↑3 | The reference here is to Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993). As a bridge to the burgeoning literatures on this subject, see Stuart Hall, “Breaking Bread with History: C. L. R. James and The Black Jacobins,” History Workshop Journal, 46 (Autumn 1998), 17-31; Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1997); Laurent Dubois, “The Citizens Trance. The Haitian Revolution and the Motor of History,” in Birgit Meyer and Peter Pels (eds.), Magic and Modernity. Interfaces of Revelation and Concealment (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 103-28, and Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004). |

| ↑4 | Frederick Cooper, Thomas C. Holt, and Rebecca J. Scott, Beyond Slavery: Explorations of Race, Labor, and Citizenship in Postemancipation Societies (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 23. These three authors’ monographs superbly address the complexities of the transitions between slavery and wage labor. See respectively Frederick Cooper, From Slaves to Squatters: Plantation Labor and Agriculture in Zanzibar and Coastal Kenya, 1890-1925 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980); Rebecca J. Scott, Slave Emancipation in Cuba: The Transition to Free Labor, 1860-1899 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985); Thomas C. Holt, The Problem of Freedom: Race, Labor, and Politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832-1938 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); and Rebecca J. Scott, Degrees of Freedom: Louisiana and Cuba after Slavery (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005). For the use of indentured labor: Hugh Tinker, A New System of Slavery: The Export of Indian Labour Overseas, 1830-1920 (London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Race Relations, 1974); David Northrup, Indentured Labor in the Age of Imperialism, 1834-1922 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995). For the historically determinate processes working to produce the nineteenth century version of “free labor,” see Robert J. Steinfeld, The Invention of Free Labor: The Employment Relation in English and American Law and Culture, 1350-1870 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), and Coercion, Contract, and Free Labor in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). I’m grateful to Dennis Sweeney for pointing me towards this reference. |

| ↑5 | See Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery. From the Baroque to the Modern (London: Verso, 1997), and The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery 1776-1848 (London: Verso, 1988); Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Viking, 1985); David Scott, “Modernity that Predated the Modern,” History Workshop Journal, 58 (Autumn 2004), 191-210. |

| ↑6 | My thinking on this point is hugely indebted to the ideas of Carolyn Steedman and in particular to a reading of her unpublished paper, “A Boiling Copper and Some Arsenic: Servants, Childcare and Class Consciousness in late eighteenth-century England,” and our associated correspondence. See also Steedman’s already published articles, “Lord Mansfield’s Women,” Past and Present, 176 (2002), 105-43, and “The Servant’s Labour: The Business of Life, England, 1760-1820,” Social History, 29 (2004), 1-29. |

| ↑7 | To the labor regimes of slavery and servitude Linebaugh and Rediker have added a third, namely that of the sailing ship, which they claim as the site of production characteristic of the Atlantic arena of globalization in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. See Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (London: Verso, 2002). Linebaugh first developed this argument in an essay of 1982, which remains foundational for what became the field of Atlantic studies: “By the end of the seventeenth century we may distinguish four ways by which capital sought to organize the exploitation of human labor in its combination with the materials and tools of production. These were first, the plantation, in many ways the most important mercantilist achievement; second, petty production such as the yeoman farmer or fortunate artisan enjoyed; third, the putting-out system which had begun to evolve into manufacture; and the mode of production which at the level of circulation united the others, namely the ship.” In Linebaugh’s argument, ships “carried not only the congealed labor of the plantations, the manufactories, and the workshops” in their holds, but also the “living labor… of transported felons, of indentured servants, above all, of African slaves.” See Peter Linebaugh, “All the Atlantic Mountains Shook,” in Geoff Eley and William Hunt (eds.), Reviving the English Revolution: Reflections and Elaborations on the Work of Christopher Hill (London: Verso, 1988), 207, 208.The essay was first published in Labour/Le Travail, 10 (Autumn 1982), 87-121. |

| ↑8 | I’m referring here to the argument in Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991 (New York: Pantheon, 1994), esp. 225-400. I’ve developed this argument in full in Geoff Eley, Forging Democracy: The History of the Left in Europe, 1850-2000 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), especially Chapter 23: “Class and the Politics of Labor,” 384-404 |

| ↑9 | The heyday of those critiques was the first half of the 1980s. See Charles Sabel and Jonathan Zeitlin, “Historical Alternatives to Mass Production: Politics, Markets, and Technology in Nineteenth-Century Industrialization,” Past and Present, 108 (1985), 133-76; Charles Tilly, “Flows of Capital and Forms of Industry in Europe, 1500-1900,” Theory and Society, 12 (1983), 123-42, and “The Demographic Origins of the European Proletariat,” in David Levine (ed.), Proletarianization and Family History (Orlando: Academic Press, 1984), 1-85; Geoff Eley, “The Social History of Industrialization: ‘Proto-Industry’ and the Origins of Capitalism,” Economy and Society, 13 (1984), 519-39. |

| ↑10 | It remains axiomatic for my understanding of the argument in these paragraphs that between the later 1940s and mid 1970s Western Europe’s period of relatively humanized capitalism under the aegis of the Keynesian/welfare state synthesis was no less beholden to systems of globalized exploitation of natural resources, human materials, and grotesquely unequal terms of trade than the periods that came before or since. The privileged metropolitan prosperity of the long boom in which social democratic gains were embedded rested (systemically, constitutively) on historically specific repertoires of extraction and exploitation operating on a world scale. Amid all the contemporary talk of colonialism and postcoloniality, of globalization and “empire,” in this regard, a workable theory of imperialism remains in urgent need of recuperation. For one starting-point, see Alain Lipietz, “Towards Global Fordism?,” and “Marx or Rostow?,” New Left Review, 132 (March-April 1982), 33-47, 48-58. |

| ↑11 | David Harvey, Spaces of Global Capitalism: A Theory of Uneven Geographical Development (London: Vero, 2006), A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), and Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (London: Verso, 2012); Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso, 2011); Göran Therborn, “Class in the Twenty-First Century,” New Left Review, 2/17 (November-December 2012), 5-29, and The World: A Beginner’s Guide (Cambridge: Polity, 2011); Pietro Basso, Modern Times, Ancient Hours: Working Lives in the Twenty-First Century (London: Verso, 2003); Guy Standing, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011); Marcel van der Linden, Workers of the World: Essays Toward a Global Labor History (Leiden: Brill, 2010); Beverly J. Silver, Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization since 1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Sam Gindin and Leo Panitch, The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire (London: Verso, 2012). |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine