For the first time in nearly a century, echoes of socialism are once again reverberating in the United States. Despite waves of “red scares,” which reduced socialism to a political disease, current opinion polling suggests that substantial numbers of U.S. citizens, especially among younger cohorts, now consider socialism preferable to capitalism. What socialism means in the twenty-first century, however, appears inchoate – especially when its new American avatar, Bernie Sanders, most often praises Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and neglects the heyday of socialism in the United States from 1910 to 1918.

It’s a shame that Sanders, who once made a documentary on Eugene V. Debs, has not said much about earlier American socialist movements during his campaign – not only because such neglect buries a vibrant history of struggle, but because it’s precisely the experiences of the movements of the past that may help us navigate some of the major challenges in building an organized socialist movement today. Like us, earlier socialists struggled to unite a fragmented and heterogeneous working class, fuse extra-parliamentary struggle with electoral politics, counter the machinations of the Democratic and Republican Parties, and above all, make socialism a real part of people’s daily lives. And for a time, they succeeded. Let us therefore look back to this period, when socialism appeared as an actual political alternative in the United States, to see what it meant to its followers, how its proponents practiced politics, what socialists did when they obtained political power, and, most importantly, how they overcame some of the dilemmas they faced while crashing against others.

The Rising Tide of Socialism

Socialism planted its roots in the United States in the late nineteenth century, just as it did in Europe, but it remained for the most part a sectarian movement of predominantly German immigrants who conducted party business, newspapers, journals, and conferences in their native language. At the turn of the twentieth century, socialism in the United States broadened its appeal, and more of its adherents spoke and wrote in English. It attracted more militant trade unionists, former Populists, social gospelers, academics and intellectuals, and a leader who spoke the language of reform and even revolution in the native vernacular. That leader, Eugene Victor Debs, had traveled a circuitous route to socialism by way of Democratic party politics, traditional craft unionism, radical industrial unionism, Populism, and utopian or communitarian socialism; he filled his oratory more with Biblical citations and phrases than Marxist terminology, more with allusions to the promises expressed in the Declaration of Independence than to the Communist Manifesto or Das Kapital, and he held his audiences spellbound whether in small towns, rural communities, or even metropolises like New York City with its diverse audience for many of whom English was a second language. 1

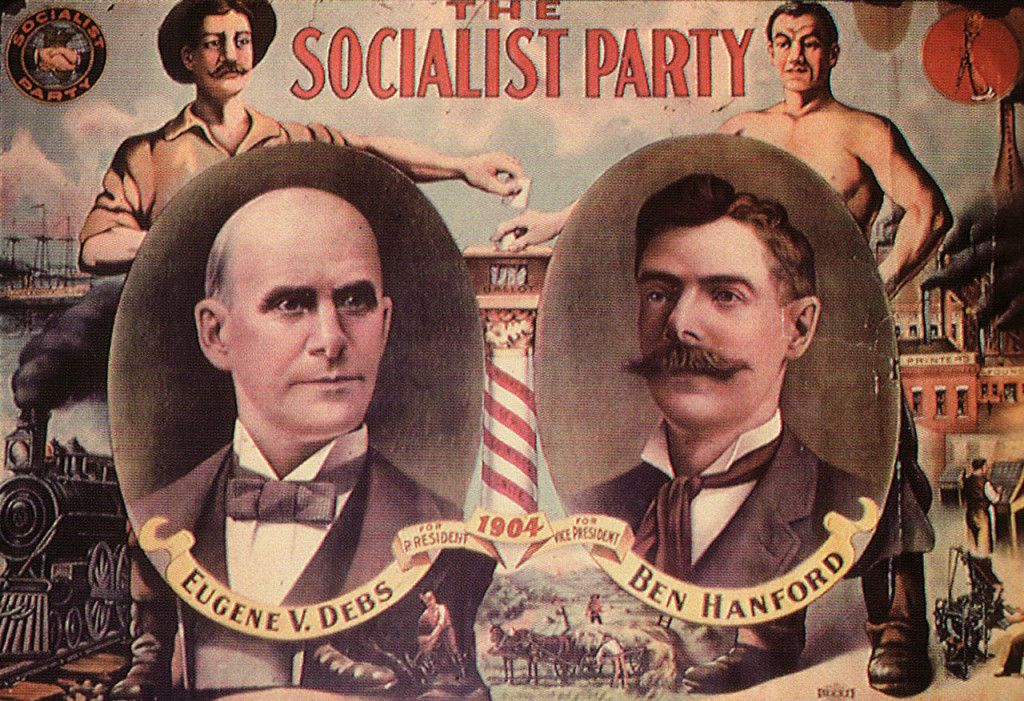

The party that Debs spoke for and for which he campaigned for the presidency four times – in 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920 – formed at a national convention in 1901. 2 The convention brought together a number of disparate groups including Jewish and other urban immigrants who had rebelled against Daniel DeLeon’s control of the Socialist Labor Party; Victor Berger’s Austro-German Social Democratic organization based in Milwaukee trade unionists; and what might be deemed the Debs’ following: remnants from his American Railway Union, agrarian and worker ex-Populists, Christian Socialists, and individuals transfixed by Debsian rhetoric. Convention delegates named their new organization the Socialist Party of America (SPA), and created a coalition as diverse as those constructed by the Republican and Democratic parties.

During its first decade the SPA experienced steady but not spectacular growth. Aside from the firm roots it planted in Milwaukee where the organization led by Victor Berger threatened the political power exercised by Democrats and Republicans in the city and county, the SPA posed little threat to the established parties. But it did have voice as reflected in its widely read newspapers and journals in numerous languages and its soapbox orators who captured the attention of crowds on city street corners and at rural camp meetings. The party published daily newspapers, such as Milwaukee’s Social Democratic Herald and New York’s Call as good or better than the other city dailies, and New York’s Yiddish-language Vorwaerts (“Forward”) was the nation’s most widely read foreign-language newspaper. The SPA also published two popular mass circulation periodicals (The Appeal to Reason, out of Girard, Kansas and the National Rip-Saw out of St. Louis), two theoretical and learned journals with global coverage (International Socialist Review and The New Review), along with journals issued by such unions as the International Ladies’ Garment Workers, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (post-1914), the United Mine Workers, the United Brewery Workers, the International Association of Machinists, and the Western Federation of Miners, which promoted socialist principles and concepts. Smaller circulation papers and journals appealed to nearly every foreign language readership in the nation. Thus, before the SPA had much electoral success it developed a loud and effective political voice – and this effectiveness was fully tied to multiple modes of address.

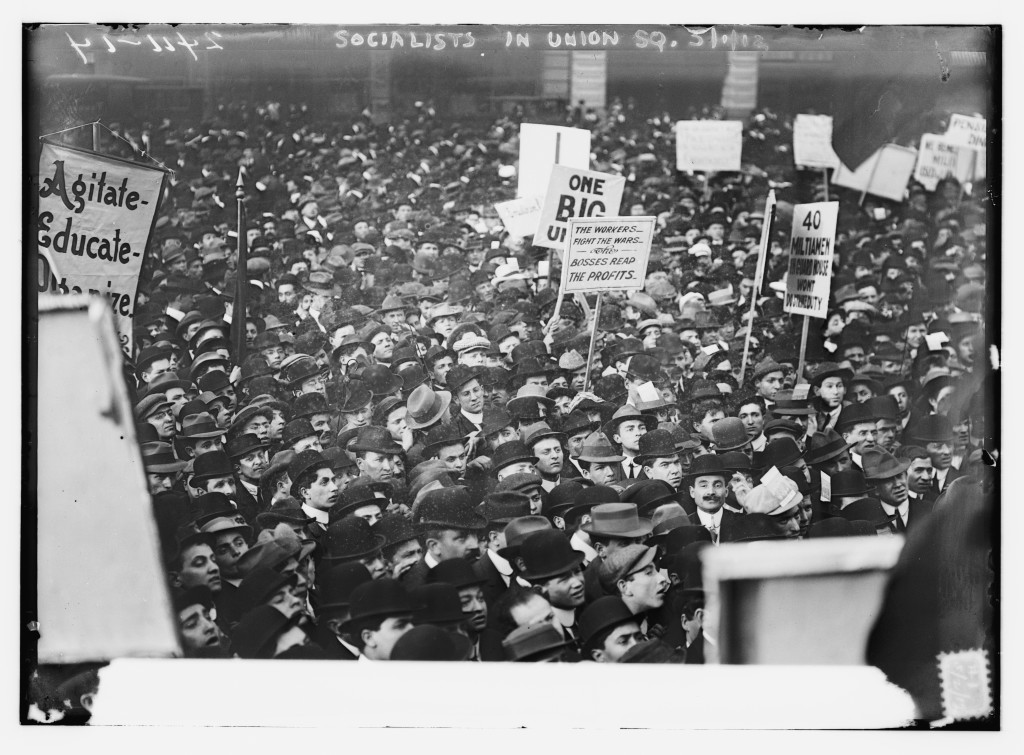

Beginning in about 1910, the economic and political universes appeared to shatter, offering wider opportunities for socialists. Between 1909 and 1913, mass and sometimes violent strikes swept across the Western world, the United States included. In New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Chicago, among other centers of the ready-made clothing industry, needle trades workers walked off the job to win higher wages, improved conditions, and union recognition. Their victories led to rapid growth in membership among unions that tutored their ranks in socialist doctrine, encouraged their immigrant members to become citizens, and ushered them to polling places to vote for SPA candidates. In cities with rising membership in garment industry unions, most notably the Ladies’ Garment Workers, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, the Cap and Hat Makers, and the Fur Workers, socialist votes increased. Simultaneously, the most radical labor organization ever to arise in the United States, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), emerged from relative obscurity to lead two general strikes in the textile industry: the 1912 Lawrence, Massachusetts “bread and roses” conflict and the 1913 Paterson, New Jersey silk strike that linked IWW radicals, New York bohemians and intellectuals (the famous Greenwich Village avant-garde and their brilliant monthly, The Masses), SPA members, and immigrant New Jersey silk workers in a common cause. The explosion of labor conflict, combined with increasing votes for SPA candidates, led to articles and essays in academic journals, small circulation magazines, and mass-market dailies heralding “the rising tide of socialism” or “the rising tide of syndicalism.”

What had happened in the United States was part of a global labor uprising that enveloped Western and Northern Europe, where equally massive strikes paralyzed major economic sectors. Germany, France, and Britain required military intervention to quell class conflict. Spain and Italy produced syndicalist and anarcho-syndicalist counterparts to the U.S. IWW, and migrant workers from both nations, especially Italy, traveled around migratory circuits that often took them to the United States. In Germany especially but also in the German-language dominant Austro-Hungarian Empire, France, Italy, and southern Europe socialists began to make substantial electoral inroads. Even in Britain a Labour Party emerged independently of the Liberal Party and its Lib-Lab coalition. Suddenly a socialist tidal wave seemed to sweep across the industrial world, the United States included. In the era of the Second International (1881-1919), socialists everywhere thought that they were riding history’s express train on an unimpeded track whose destination was a cooperative commonwealth among equal citizens.

The Bases of Socialist Success

Nationally, the presidential election of 1912 established the presence of the SPA as an electoral force. Debs, in his fourth race for the presidency, drew almost a million votes or between 6 and 8 percent of the total. By 1914 the party had elected two members of Congress, Victor Berger from Milwaukee and Meyer London from Manhattan. By then the party counted a membership of over 100,000 men and women who paid regular dues and committed themselves to the party’s principles, unlike Democrats and Republicans who typically were only nominal party members. The SPA continued to print hundreds of newspapers and magazines and to maintain a significant political voice. At the local level at various times between 1910 and 1916 the SPA controlled municipal governments in Schenectady, New York; Reading, Pennsylvania; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Dayton and Toledo, Ohio; Granite City, Illinois; Butte, Montana; Berkeley, California, and numerous other cities. Socialists remained a potent influence in the labor movement. At least one-third of delegates to the 1911 AFL convention were socialists by conviction or party membership, and socialists exerted a dominant influence in four of the largest affiliates of the AFL and two of the smaller ones. Outside of the AFL, the mass membership Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America promoted socialism among its members and even members of the syndicalist IWW, who expressed antipathy to conventional politics, could be counted on to vote socialist when and where they were eligible to do so. 3

Socialism acted as part of the general wave of reform sentiment sweeping the nation associated with the Progressive era. Indeed one of the more notable progressive reformers, Charles Sprague Smith, an influential New York progressive and founder of the popular People’s Forum, wrote to SPA leader Morris Hillquit that “what I feel about Socialism is that it is a very important element in the whole Progressive movement…” 4 In the 1912 presidential election, 75 percent of voters chose change in one form or another. Only 25 percent opted for the candidate of the status quo, William Howard Taft; the vast majority cast ballots for Debs, Woodrow Wilson, the eventual victor, or Theodore Roosevelt, who ran as a progressive outside the Republican party.

Equally remarkable was the SPA’s attraction for leading intellectuals, literary celebrities, and artists. The membership list for Local One of the New York City SPA, which spread from Greenwich Village through Chelsea on the West Side, read like a who’s who of the city’s cultural elite. Among its members at one time or another were the novelist Theodore Dreiser, writer and editor Max Eastman and his sister, the lawyer, journalist, and feminist Crystal Eastman, the painters John and Anna Sloan, the journalist Mary Heaton Vorse, the notable female reformers Florence Kelley and Frances Perkins, the socialites William English Walling, Robert Hunter, J. G. Phelps-Stokes, and the young Walter Lippmann. Such African American radicals as W.E.B. Dubois, A. Philip Randolph, and Hubert Harrison found for a time a comfortable home in New York’s SPA. Elsewhere such prominent literary figures as Jack London, Upton Sinclair, and Carl Sandburg joined the party.

Wherever the socialists established municipal power or influence the party constructed an alliance with local unions of skilled workers. Once in power the socialists delivered clean, efficient government services. In the case of Milwaukee, this led to its reputation as the nation’s healthiest city. Unlike many of their Progressive competitors the socialists did not seek to disenfranchise or disempower poorer citizens, and they brought paved, clean streets, municipal water and sewer service, public health provisions, public utilities, and good schools to poor as well as wealthy citizens. Though more radical socialists may have criticized their more moderate comrades as “gas and water socialists,” the citizens who received gas, water, and other such public services appreciated them deeply. 5

The SPA built a constituency that spread across length and breadth of the country. Its largest state party branch by proportion was in Oklahoma, with a somewhat smaller branch in the neighboring state of Kansas. In Huey Long’s Louisiana home parish, Winn, the party proved a powerful presence; and in Arkansas, east Texas, the Mountain States, and the Far West the SPA drew support among tenant farmers, sharecroppers, coal miners, hard-rock miners, and railroaders. 6

Party leaders cultivated their relations with affiliates of the AFL despite periodical condemnations of socialism by Gompers and his closest associates on the Federation’s executive council. The gospel as laid down by party leader and theorist Morris Hillquit, as he drew it from the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, read as follows:

I am firmly convinced that the success or failure of our movement…will ultimately depend on our ability to win the support of organized labor. We cannot assume that the organized workers…are constitutionally inaccessible to the teaching of socialism. If we do, we might as well give up all hope of ever winning power or influence in…political life…

Hillquit added that labor unions “are the best fields for propaganda in so far as they are organized on the basis of class struggle. It makes them more accessible to the teachings of socialism.” 7 To which a young woman garment worker noted, “Isn’t it possible to have more control of such trade unions, and to make them not only trade unions but idealistic unions and to make propaganda? Then we socialists will have more votes…” 8

The Socialist Mentality: Simple Truths and Hard Dilemmas

It is easy enough to know what socialism meant for party leaders (they expressed their beliefs often enough in speech and writing) but it is much harder to determine what socialism meant for most SPA members and voters. In simplest terms, socialists probably believed in production for use not profit; solidarity in place of the individualistic Darwinian struggle for advancement; humankind as the maker of society rather than impersonal natural law as the molder of humanity; and justice rather than wealth as the foundation for society:in brief, a social order in which the ties that bind people together were stronger than those which separate them, and in which actual material equality replaced formal, or false bourgeois, equality. For many socialist voters, however, the more quotidian aspects of their politics – job security, better working conditions, clean government, and superior public services, in other words, “gas, water, and sewer socialism” – attracted their devotion. And it was a political movement that, again in the words of Hillquit, “…has changed its practical methods somewhat. It always does. It learns from experience. It is not any more conservative today than it was twenty years ago.”

Yet a series of sensitive issues – immigration, race, and feminism – created dilemmas that SPA never resolved satisfactorily. An organization that drew support among newer immigrants and their children, the SPA resisted most attempts to restrict immigration that were aimed at emigrants from the east and south of Europe. Socialist doctrine taught its adherents not to draw distinctions among workers of the world who were united in the Second International. Yet in the U.S. racial beliefs dominant among trade unionists, and even among many socialists, drew a firm line that separated Asian immigrants from others, denying them the right to emigrate to the U.S. Some socialists, like Victor Berger, supported Asian exclusion in explicitly racist terms but others, like Hillquit, rationalized such a policy by maintaining that if “Coolie” laborers stayed at home, they would intensify class conflict and impel revolution in their homelands. 9

Racist sentiments also limited the SPA’s inroads among African Americans who remained concentrated in the former slave states where de jure segregation ruled. Socialist branches everywhere in the South were “Jim Crowed” and the vast majority accepted only whites. The party equivocated on the woman question. Women found much more opportunity to serve in the SPA as speakers, writers, and party officials than was the case in both of the major parties. And the SPA, unlike the Republican and Democratic parties, uniformly demanded woman’s suffrage and campaigned for it. Still, all too many of the men who dominated party leadership and formed the bulk of the rank and file believed that women’s place remained in the home. 10

Unable to resolve the internal divisions arising from immigration, race, and gender, socialists insisted that racism and misogyny would be superseded with capitalism and its class distinctions, relieving their program of any present responsibility. While this treatment of those distinct oppressions leaves much to abhor, we should be careful about how we criticize them. Situating racism and misogyny, for instance, in the dynamics of capitalism has been a cornerstone of the black radical and Marxist Feminist traditions. The deficiency of SPA’s approach came not from a narrow preoccupation with the working class, but an improper theorization of how the class was structured by those other elements of the social formation. It was a failure to impute struggles around immigration, race, and gender with a socialist content, and produce, beyond the fragments, a unified proletariat.

The debate that roiled European socialists before World War I – the intra-party conflict between adherents of evolutionary (reform) socialism and advocates of revolutionary socialism (Bernstein vs. Kautsky), or between traditionalists and revisionists – had only the faintest echoes in in the United States. The SPA espoused traditional Marxism in its theory and language, but in practice it implemented a revisionist program of piecemeal reforms and incremental electoral gains. The clash between revolutionary doctrine and reformist practice emerged clearly in 1912 and 1913 when the SPA divided internally over the issue of confrontation and violence. In 1913 the party majority ousted the IWW’s William D. Haywood from the party’s national executive committee because he advocated direct action, sabotage, and refused to reject violent methods. Haywood’s repudiation by a party majority proved that despite its revolutionary rhetoric, the SPA majority in practice followed the revisionist prescription offered by Bernstein, that is, the party assumed that the cooperative commonwealth would be achieved by electoral action and not a massive general strike or revolutionary action. 11

The greatest dilemma for U.S. socialists remained how to convert the majority of trade unionists and workers to their cause. Unlike continental Europe where socialist parties and trade unions emerged together and where socialists often birthed unions, in the United States nearly all the affiliates of the AFL and the largest unaffiliated unions were founded before the birth of the SPA. Unlike Europe, where the socialist movement was instrumental in winning franchise rights for workers, in the U.S. adult male workers obtained the right to vote prior to the emergence of socialism and developed loyalties to one of the two major parties. Unions in Europe and the United States, moreover, existed to bargain with employers and protect workers’ rights on the job. How then might unions bargain regularly with employers and still remain faithful to a movement committed to expropriating capitalists? In other words, how could socialist unions function effectively within an existing capitalist system and still maintain a Marxist, revolutionary position?

A host of other factors limited socialist penetration among workers and the general population. In the South and in places like Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas the SPA drew its support mostly among U.S.-born and older-stock immigrant groups. In major metropolises and smaller industrial cities, the party appealed most commonly to workers of more recent immigrant groups. Before World War I, however, substantial numbers of south and east European immigrants remained sojourners and not citizens, hence unable or unlikely to vote. As the case of New York City and, to a lesser extent, Milwaukee revealed, ethnic divisions circumscribed socialist strength. Irish, Italian, and Jewish Americans dominated New York City’s population. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Irish had been fully integrated into the city’s Democratic political machines (a similar dynamic played out in Milwaukee). Italians, many of whom were still not citizens, voted in sparse numbers. Only the east European Jews, who became citizens relatively rapidly, and who dominated the garment industry unions and preferred to read Vorwaerts, could be relied on to vote for SPA candidates. Congressman Meyer London represented a largely Jewish district as did nearly all the New York socialists voted to municipal and state office. 12

The realities of the American trade union movement also limited socialist success. Gompers and the political machine that he constructed within the AFL waged ceaseless warfare against socialist penetration of the Federation. And among the unions led by socialists, the more they succeeded in wresting concessions from employers with whom they bargained, the less socialism appealed to the rank and file who took the money and ran.

World War and the Crisis of Socialism

None of this, however, dissuaded American socialists prior to World War I that their future prospects were circumscribed. At first U.S. participation in the war redounded to the advantage of the SPA. Unlike European socialists who had fractured when war erupted in the summer of 1914, with the majority among them choosing nationalism over internationalism, the SPA categorically rejected U.S. entry into the conflict and initially paid no political price for its decision. In fact, in New York City and elsewhere the SPA won electoral victories in municipal and state elections in 1917 and 1918. Morris Hillquit amassed more votes in 1917 as a candidate for New York mayor than any previous third-party candidate, and the SPA elected ten state assemblymen, five aldermen and a municipal judge. A year later the SPA amassed as many votes but managed to elect only one of its candidates (a state assemblyman) because in all the other state assembly districts and Meyer London’s congressional district, the Democratic and Republican parties ran joint candidates. The Milwaukee party experienced similar success maintaining its control of local government and returning Berger to Congress. 13 Local electoral successes in 1917 and 1918, however, disguised a more somber reality. The SPA may have rejected U.S. participation in the war but only at the cost of losing many of its U.S.-born members, several of whom became active servants of the Wilson wartime administration.

Wartime patriotism, moreover, resulted in the savage repression of antiwar socialists. Congress refused to seat Berger after his reelection in 1918. Two years later, the New York State legislature similarly refused to seat newly elected SPA assemblymen from New York City, even after their constituents gave them a second electoral victory (the SPA, however, did reelect London and Congress allowed him to serve). Debs and other socialists paid an even higher price for their resistance to wartime patriotism, indicted and tried for violation of the espionage and sedition acts passed in 1917 and 1918 and sentenced to terms in federal penitentiaries. The government leashed the socialist press by denying SPA papers and magazines the right to mail copies to subscribers or to sell publications at commercial outlets. The party’s once loud voice had been silenced. And then the Bolshevik Revolution and the creation of the Soviet Union rendered perhaps a final shock to the SPA. The bulk of the party’s foreign language federations and many of its younger and more active American-born members, John Reed, James Cannon, and Max Eastman most notably, bolted to join one of the two new communist parties that had emerged in 1919. The combination of wartime repression and communist competition spelled doom for the SPA. Despite one last hurrah, Debs final campaign for the presidency in 1920 while still imprisoned, the SPA was doomed as an effective political force. 14

Socialism remained alive and well in Milwaukee, where socialists held local political power well into the 1950s, in Bridgeport, Connecticut among several similar smaller industrial cities, and among Jewish Americans concentrated in the garment trades unions and most especially in New York City where they continued to read the Vorwaerts. Nationally, however, the SPA never recovered from the blows delivered by world war and then followed only a decade later by the Great Depression and the New Deal. By the middle of the 1930s three worlds circumscribed the lives of the garment trades unionists, the readers of the Forward, and New York’s Jewish Americans, “di welt, yene welt, un Roosevelt.” 15 The party may have lived on institutionally even as it lost the bulk of its members and voters to the New Deal Democratic party, New York’s American Labor Party or Minnesota’s Democratic Farmer-Labor Party, but not without enduring yet more internal warfare, additional desertions, and competing versions of socialism. Each faction preached to an ever smaller chorus of its true believers, a steadily shrinking “amen corner.” 16

Socialism Today

Despite decades of defeat, it’s undeniable that socialism has once again crept back into the mainstream. In 2011, a Pew Poll revealed that 49 percent of Americans under thirty had a positive view of socialism, a finding confirmed in more recent polls. Nothing illustrates this new openness to socialism more than the candidacy of Bernie Sanders. But even with this new energy, a number of questions and challenges remain. What, for example, does socialism mean to all those who profess an openness to it today? A reborn New Deal, the abolition of capitalism altogether, or something in between? Just as socialists ceaselessly debated and discussed the meaning of the term a century ago, we will have to collectively redefine socialism for our own time.

More importantly, even if socialist sentiment is undeniably on the rise, an organized socialist movement is only in its infancy. As we continue to reflect on how to transform this new interest in socialism into an organized political force, the preceding history of the SPA could provide some direction. Of course, historical conditions have changed enormously. Gone are the days of growing industrial factories, a relatively limited and decentralized state, and a seemingly ever-expanding labor movement – all factors in the SPA’s rise. Nevertheless, some of the keys to the SPA’s success may still serve us today – the need to encourage a vibrant, diverse, multi-lingual socialist press; to link with immigrant struggles; to foster a socialist ecosystem composed of various overlapping groups, associations, and movements; and to connect with the self-activity of different kinds of workers across the country, which, in our time, might help revitalize a militant workers’ movement.

Above all, the SPA highlighted the strategic potential of electoral struggle. In the early twentieth century, socialists built a movement on the dynamic circuit between electoral struggle on the one side and the innumerable extra-parliamentary struggles on the other. It remains to be seen if the Sanders campaign – as well as other, more local, electoral campaigns – can do the same today. In this respect, the history of the SPA may once again offer some insight by highlighting the many limitations, challenges, and dangers of socialist organizing, especially at the electoral level. Can the Sanders campaign effectively connect with pre-existing struggles, such as the fight against racism or the struggle for a fifteen dollar minimum wage and a union? Is his campaign opening spaces for other socialists to run for office at a state or local level? And are the Democrats poised to once again sweep up the hard work done by socialists? These are the questions we must answer as we try to redefine “socialism” for the twenty-first century and forge an autonomous socialist movement.

References

| ↑1 | Two excellent biographies offer readers all they need to know about how and why Debs became a socialist and the sources of his popular appeal. Ray Ginger, The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1949) and Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1982), the more recent and perceptive study. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | During his first run for the presidency, in 1900, Debs ran on the Social Democratic Party of the United States (SDP) ticket, since the Socialist Party of America had not yet been formally established. |

| ↑3 | For an older but still useful history of the party, see David Shannon, The Socialist Party of America (New York: Macmillan, 1955). For more recent and superior histories, see James Weinstein, The Decline of Socialism in America, 1912-1925 (NY: Monthly Review Press: 1967), chapter 2 for the heyday of socialist electoral success, and Jack Ross, The Socialist Party of America: A Complete History (Lincoln: Potomac Books, 2015), chapters 5-6. |

| ↑4 | Melvyn Dubofsky, “Success and Failure of Socialism in New York City, 1900-1918: A Case Study,” Labor History 9 (Fall 1968): 374. |

| ↑5 | Judith Walzer Leavitt, The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996) and Sally Miller, Victor Berger and the Promise of Constructive Socialism, 1910-1920 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973), see especially chapters 2-4. |

| ↑6 | James R. Green, Grass Roots Socialism: Radical Movements in the Southwest, 1895-1943 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978); Carlos Schwantes, Radical Heritage: Labor, Socialism, and Reform in Washington State and British Columbia, 1885-1917 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979). |

| ↑7 | Dubofsky, “Success and Failure,” 363. |

| ↑8 | Ibid. |

| ↑9 | Miller, Victor Berger, 51-53. |

| ↑10 | Mari Jo Buhle, Women and American Socialism, 1870-1920 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1983); See also, Weinstein, The Decline of Socialism, 53-73. |

| ↑11 | Ross, The Socialist Party of America, chapters 5-6. |

| ↑12 | Dubofsky, “Success and Failure,” 366-72. |

| ↑13 | M. Dubofsky, “Success and Failure,” 370-72; Weinstein, The Decline of Socialism in America, chapters 3; Ross, The Socialist Party of America, chapters 6-7. |

| ↑14 | J. Weinstein, The Decline of Socialism in America, chapters 3-4; Ross, The Socialist Party of America, chapters 7-8. |

| ↑15 | Irving Howe, The World of Our Fathers (New York: Harcourt, 1976), 393. |

| ↑16 | Ross, The Socialist Party of America, chapters 12-20 provides the most complete history of the SPA’s sad later years. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine