There has been a rapid growth of companies offering food delivery services through online platforms, including: Deliveroo, UberEATS, Amazon Restaurants, Foodora, foodpanda/hellofood, and Seamless, to name a few. The basic premise is to replace existing arrangements for takeaway delivery food, centralizing the process on an online platform. There are similarities with Uber’s business model, seeking to (as the current popular term states) “disrupt” an existing business model. The emergence of these companies connects eager venture capital with startup founders, often trying to hide the labor of the workers on which the platforms rely. Yet, the branded uniforms of these companies—either on bicycles or mopeds—have becoming an increasingly common sight in major cities.

In the UK there has been another wave of disruption, but not one that had been planned for in these new business models. In July 2016, the UK Border Agency (UKBA) raided multiple Byron Burger restaurants in central London, as well as the Deliveroo recruitment office, carrying out a mass arrest of undocumented workers. This was a collaborative trap fabricated by the state and businesses. Deliveroo’s workforce is largely populated by immigrants, and Byron Burgers is one of Deliveroo’s key partners. Once the news spread, many riders began boycotting Byron orders, refusing to deliver their food to customers. The message was spread through WhatsApp, social media, and moved, through the drivers, into different parts of the city. These combined to create a climate in which there was greater cohesion and solidarity. The connections between the multiplicity of socio-spatial layers were thickening.

Two weeks after the raids, emails and texts were sent to every Deliveroo rider stating that pay was being changed to £3.75 per delivery. Previously, cyclists earned £7 per hour, plus £1 per delivery, while moped drivers earned £10 per hour, plus £1 per delivery. This new per delivery rate was understood by many as a dramatic pay drop, or at least perpetual precarity and the possibility of days without pay.

The next day Deliveroo workers organized a wildcat strike that lasted for six days. News of the strike spread first on social media, with workers gathering in their zone center 1 to meet and organize. Across the city, workers met, and remaining logged out of their applications, headed up to Deliveroo’s head offices in central London. There were hundreds of workers there, revving moped engines, beeping horns, dancing in the streets, and doing wheelies, all while shouting “No drivers! No Deliveroo!” up at the office windows. It was playful and fun, something that could be shared between those who do not necessarily speak the same language – after all, everyone can share the enjoyment of having a go at the boss. There was rage, particularly a confrontation between a manager and a dozen drivers still wearing motorcycle helmets with the visors down. But also, there was laughter.

People were arriving in convoys, as they had gone from zone center to zone center, spreading the news and recruiting anyone they came across in uniform. The management had no idea what they had let themselves in for. The Silicon Valley mentality seemed to pull a blank when it came to unofficial unions and grassroots solidarity. Their dots on maps all vanished, only to appear again as a physical presence, outside their offices en masse. On the second day, when negotiations were clearly not going well, a group of 20 almost stormed the office to occupy it, before being held back by other more patient strikers and a IWGB 2 union representative. By the sixth day, Deliveroo had to walk back the policy change, claiming now that the move to the piece rate was optional and would only be trialed in one zone.

In the wake of the victory of the wildcat strike, the next challenge was finding a way to translate that resistance into something with longevity, something that could be channelled into new organizational forms that could continue to mobilize. The IWGB, a small base union, recruited rapidly at the strikes. At points, both of us stood waving membership forms, with a queue of workers waiting to join. This is not the kind of experience either of us have found with the larger trade unions in London. From the strikes last year, the campaign in London has continued, along with other moments across the UK (for example in Bristol, Leeds and Brighton). 3 This has involved not only the IWGB, but also branches of the IWW, but no mainstream trade union has been involved. In London the campaign is currently tied up in legal and employment tribunals. The IWGB is making a claim to be recognized as the union in one particular zone and, if successful, this will mean the employment status will change from self-employed independent contractor to worker status. A success would mean much greater employment rights, including minimum wage, holiday and sick pay, and so on. This moment has less space for worker agency to shape the decisions. At first it involved a sustained organizing campaign in the zone, but it is now being deliberated at tribunal. The union provides an important space to meet with other workers and formulate demands, but this piece will focus on the experiences of the labor process in particular. What the past year has shown is that these workers in the “gig economy” have become visible. They are finding new ways to resist, continuing to meet and organize, and this can not be hidden behind the digital platform forever.

On Deliveroo

Our focus will be on Deliveroo, who uses a stylized Kangaroo and turquoise branding. Across London the drivers have become ubiquitous, whether at road junctions or gathering near restaurants between deliveries. The company is estimated to have at least 20,000 drivers and cyclists across 84 cities in 12 countries. 4 To date, it has received just under $475M in funding. 5 Deliveroo has tried to differentiate itself from the competition by offering a way for customers, they claim, to “order amazing food from the best loved local restaurants who otherwise may not offer delivery.” It is complete with a founding myth about the CEO, a former investment banker, arriving in London from New York and being frustrated at the options for food. The solution was to develop an app, through which Deliveroo would “personally curate a high-quality and diverse selection of restaurants … the only thing you will not find on Deliveroo is low-quality takeaway restaurants.” 6

Deliveroo uses a legal arrangement similar to Uber to employ drivers on the platform. Technically, the drivers are categorized independent self-employed contractors. Deliveroo uses this status to claim that their drivers come from a broad network of entrepreneurs, rather than entering into traditional employment relationships. This implies that drivers are free to offer their services to a range of companies and can even send someone else to complete the deliveries. It is part of a process of “digital black box labor” in which the labor component of platforms is deliberately obscured. 7 Yet drivers have to pay a deposit to receive their uniform and are expected to wear them while completing pre-arranged shifts. It is an attempt to divest the company from the fiscal protections – minimum wage, holiday pay, sick pay, and so on – afforded to and won by workers. Increasingly, the prevalence of “black boxes” in society is hiding work and the experience of workers. 8

In this piece, we draw attention to the labor process at Deliveroo and what it is like to work on the platform. It has been collectively written between the Deliveroo driver Facility Waters (a pseudonym), and Jamie Woodcock, who is employed at a university where he researches work. We have experimented with different ways to collect and share information about working at Deliveroo. In particular, we have tried to peel back the black box, emphasising that work on Deliveroo is not seamless, but rather it takes place in specific geographic locations in the city. We draw on inspiration from workers’ inquiry, which readers of previous issues of Viewpoint Magazine will be familiar with. Our experiment here is an adaptation of the ‘full fountain pen’ method, in which “intellectuals would be paired with workers … they would listen as the workers recounted their story, write them down on their behalf, and then have these workers revise the written documents as they saw fit.” 9 Although in our case one is not writing on the other’s behalf. Instead, we have collaboratively written on Google Docs and augmented our analysis with GPS technology and interactive maps. We encourage readers to explore the interactive map alongside the text.

Part I

Applying to Deliveroo

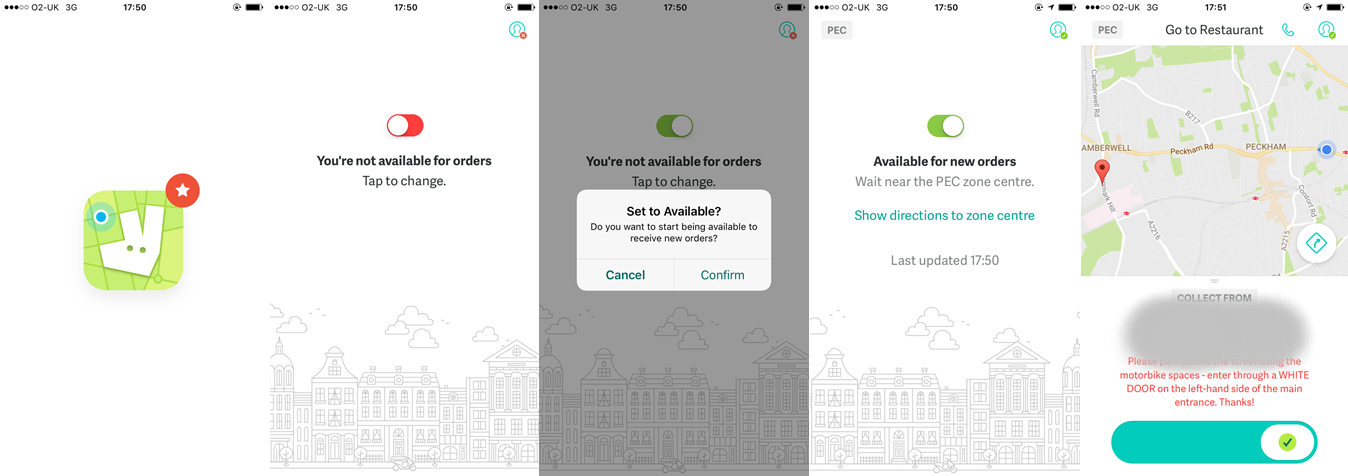

The application process to work at Deliveroo involves filling out an online form (see Figure 1). This means that if you are looking for work you can start quickly, as Deliveroo could have you on the job within three days. Deliveroo has been investing heavily in public relations, both for new customers, but also aggressively recruiting drivers. Both authors have received leaflets in the mail and have seen an increase in targeted advertisements on social media, particularly since starting the research and writing process. The tone of the material channels Silicon Valley, combined with an informal style, presumably something that tests well in focus groups for so-called millennials. The Kangaroo logo gives the excuse to include ‘Roo’ into other words, for example: ‘foundeROO’ or ‘Roowomen and Roomen’ to refer to drivers. But most of all the advertisements for potential drivers stress the ‘flexibility’ of the role.

Although the process for this particular job blurs with many of the others, I was notified that the online application was successful. I was called in to a temporary Deliveroo recruitment center – a warehouse converted to house, a call center, and somewhere to hand out equipment. The “interview” is not really an interview, instead meaning I turned up and had my bike given a basic inspection. Following this, I sat at a laptop to take a test – although it was not that hard as you can keep refreshing until all the answers are correct – and was then taken out on the roads for a further test. This involved cycling with another interviewee and a trainer, following the instructions on a smartphone app. The requirement was to navigate successfully to the location, not running any red lights, although it was not clear if there was a time limit. After reaching the first location, the second interviewee navigated to the next, then the group returned back. After a brief safety talk, there was another visit to the laptop, this time to fill out five years of previous addresses with exact dates and employment history, along with submitting to a credit check. None of these aspects were explained, nor were they present in the contract, and seemed excessive given the self-employed contractor status.

This feeling of losing control and becoming employed continued in the next steps. I was taken into the call center section, where another worker (also on a temporary contract) was called over to take my phone. They downloaded the Deliveroo app and ensured it was set up correctly. Following this, I was given a reference number and directed to a line to wait for equipment. Every worker has to pay a deposit, receiving the uniform and either a backpack or a delivery box (see pictures in later figures). On reaching the front of the line, another temporary worker tried to give me a box. These are the least preferred option as they have to be attached to the bicycle, giving less flexibility than the backpack. It also means at the end of the shift it can only be removed by dismantling it from your bike. This compares much less favorably than the backpack, which is more like the uniform, and can be easily removed after work. Either way, all the equipment can only be received if the worker pays a substantial deposit. The process is similar to induction at a call center on a zero hours contract, 10 starting with a large number of people in the room trying to figure out what is going on. It is not immediately clear what the job will involve, nor how long people will last on the contract. However, unlike the call center, at Deliveroo you cannot see how many people leave in the first week, as from this initial meeting people are distributed into different zones across London.

The workforce at Deliveroo is split between moped drivers and bicyclists. The moped drivers work longer shifts, usually covering the entire day, and work much more frequently. The cyclists tend to work over lunchtime and evenings, picking up the extra demand as people order food mostly at these times. There are difficulties assessing exact numbers or ratios of mopeds to bikes – something that Deliveroo keeps to themselves like the overall numbers of drivers – but in general the moped drivers are predominantly migrant and male. On the other hand, the cyclists tend to be younger, mostly closer to 18 years old, and many are working alongside studying for A levels 11 or university degrees. There are comparatively few women working at Deliveroo, but significantly more work as cyclists than moped drivers. White English people are the minority across both the roles. Both require complex driving skills as the riders navigate the traffic in London, but the cyclists also need a high level of fitness in order to complete the work.

A Day Riding for Deliveroo

My shift begins in the basement of the shop that I work in. Stooping a little, I put on my waterproof trousers and jacket before putting the lights and water bottle on my bike. I zip the battery block in one pocket with the charging cable plugged into my smartphone in the other pocket. I pick up my bag and make my way to street level.

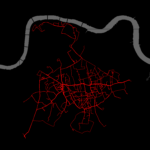

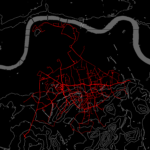

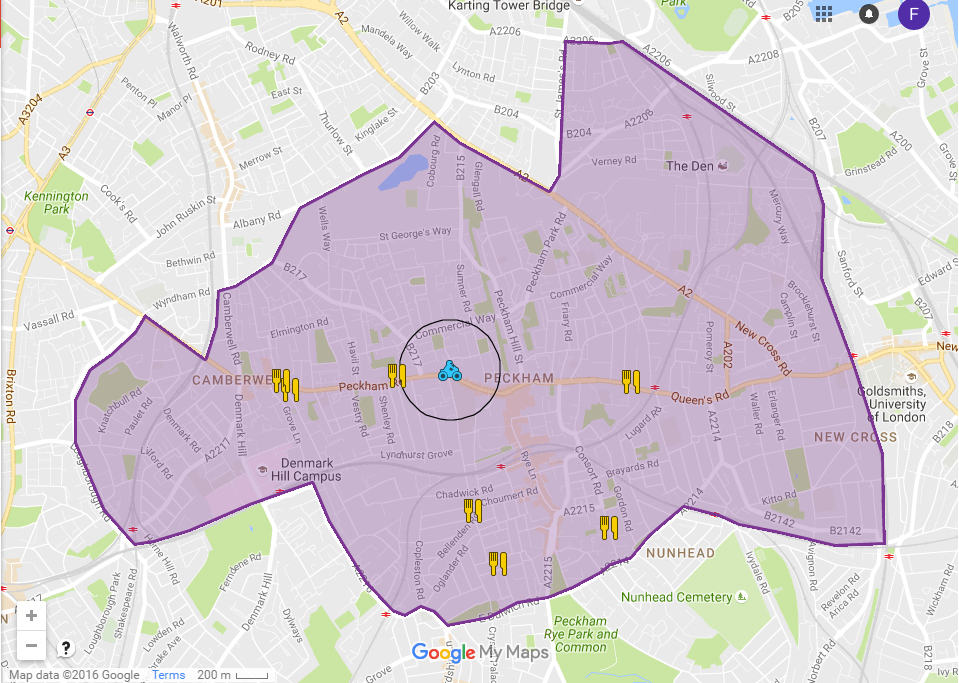

Every shift begins from home before I make my way into the zone center, the area that you have to be within to be able to clock in, cycling along one of South London’s main arteries, waiting to get to where Montpelier Road splits off of Queens Road – knowing that this is precisely the outer limit of my zone center (see interactive map). Looking at the map you’ll notice ‘ends’ to my shifts. This is because like many people in cities, where I can afford to live, is not where I was working. It also demonstrates, how I effectively turn my commute from a 30 minute cycle into a 3 and a half hour ‘extra’ shift on top of my main job.

I continue cycling while using the phone, and within a minute of clocking in I receive my first order. We only have the option to accept deliveries, and the only way to skip them is to ignore them, which takes a few minutes for Deliveroo to unassign you. Supposedly, this is bad for your ability to continue working for them, however we rarely receive any official clarification, and largely rely on sharing information and experiences between workers. I carry on cycling to Nando’s in Camberwell going past Kelly’s Avenue, the central point of our zone, where riders are suggested to wait for orders as it is should be roughly central to the restaurants we deliver from. It is here that riders gather, unlike with Uber and other platforms, meeting each other and building offline connections.

Today there is no-one there though, because I logged on 40 minutes before our shift starts. I did this because on other Sundays I have logged on early and been paid my hourly rate regardless of when I was officially down to do so. Sometimes this works, sometimes it does not. While I am certain there are specific criterion that Deliveroo payroll are using, I have no certainty of what these actually are. The other riders and I have our superstitions, but very little concrete knowledge.

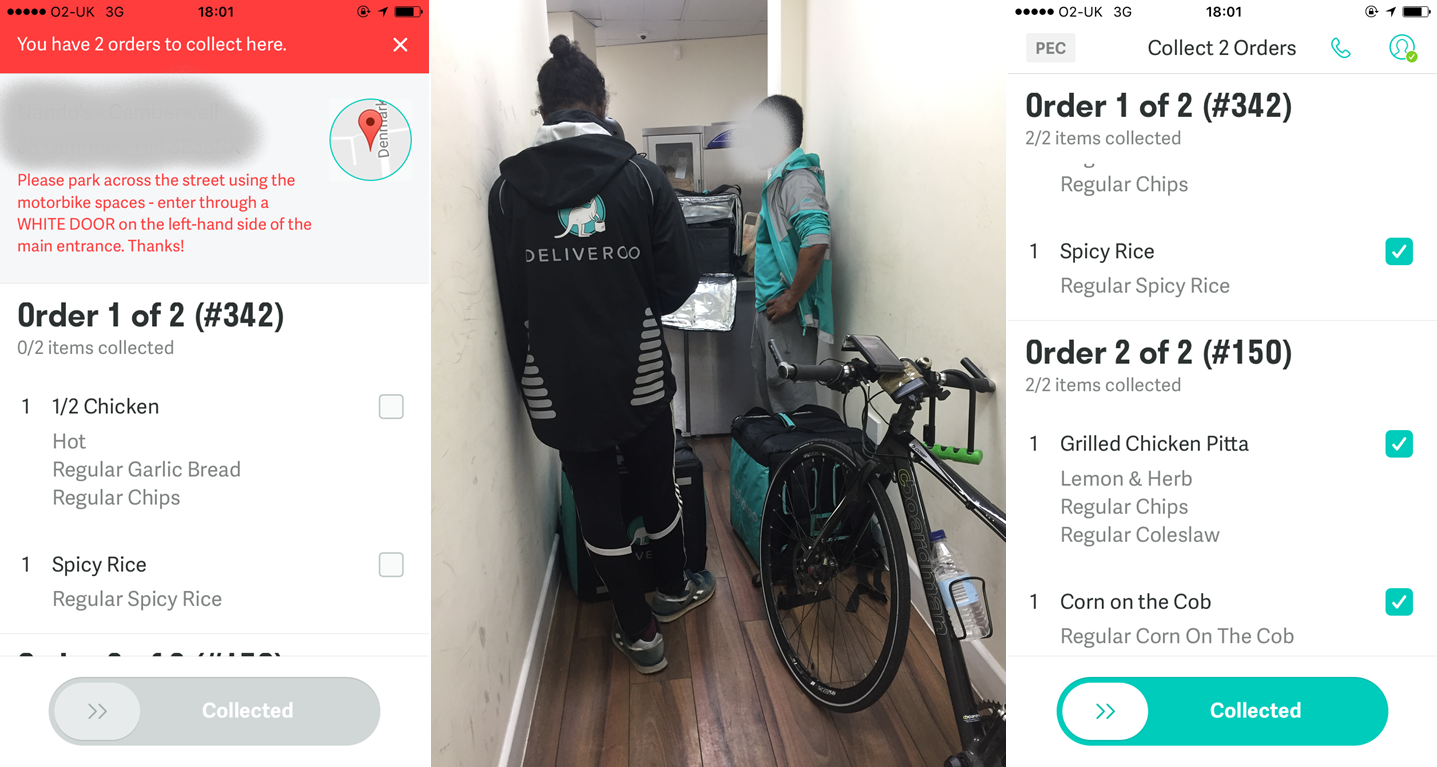

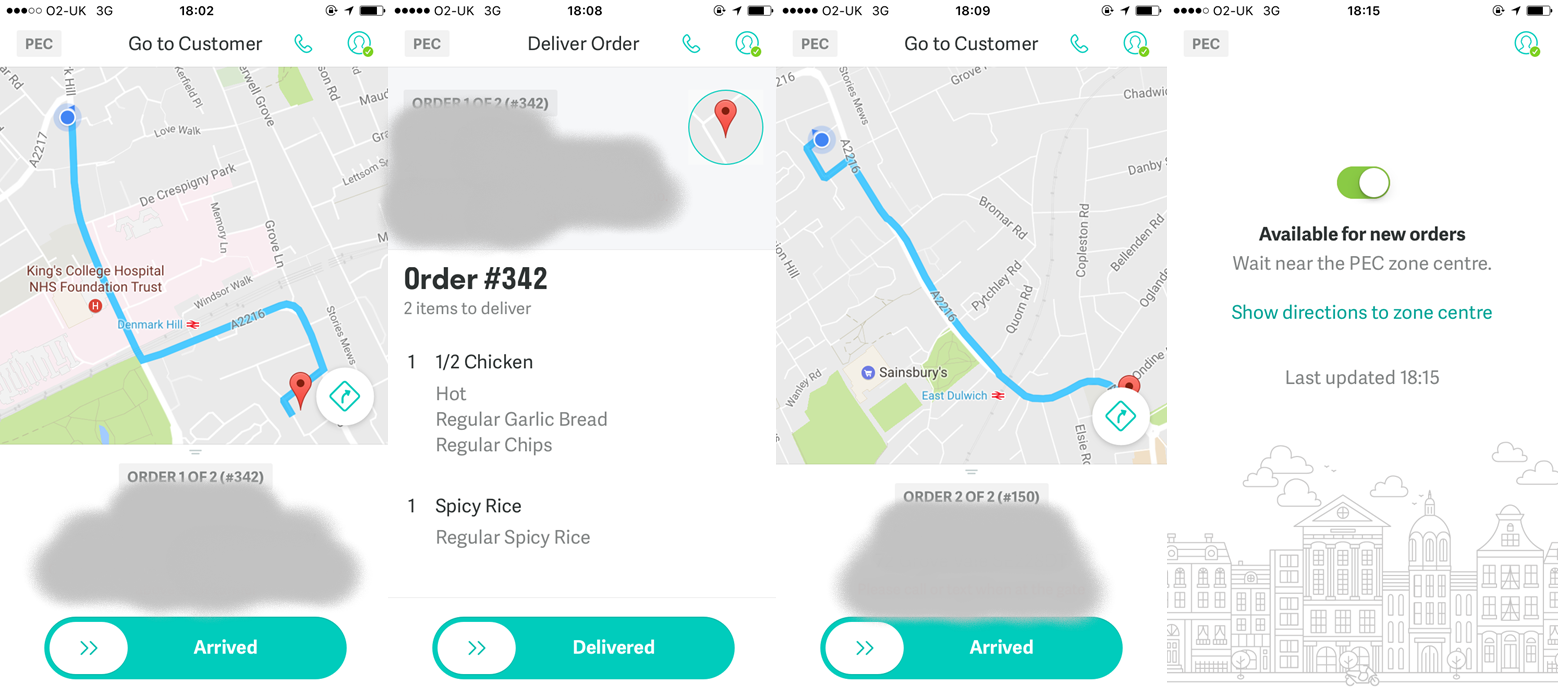

I get to Nando’s restaurant 10 minutes into my shift. Here we have our own corridor and counter, which is attached to the main kitchen but a separate operation to the front of house services that the restaurant provides. When I get close enough to Nando’s I can confirm my arrival and progress to the next screen, where I find out what I am meant to be picking up. Here it is not the listed food which really matters but the order number. As riders, we put responsibility for the order being correct with the restaurants, even if we are technically meant to be another point of quality control. I find I have been given a stacked order, meaning I pick up 2 deliveries at the same time. Again, the only option is to accept this, unless you are willing to phone the support line, be on hold for 5-20 minutes, ask to be unassigned, and have a note put on your record. I get the food in brown paper bags which are stapled shut and a numbered ticket attached. I put the orders in my thermal bag, zip up, and swipe through to the next screen on my phone.

Finally, I now get to see where I actually need to go, and it is straight uphill. Six minutes later I get to the customer’s address, walk up their steps, and wait at the door. I give them their food and swipe through to see the next address: straight over the hill, down to a gated apartment building in Dulwich, and hand over the food to the next customer 5 minutes after the last. After confirming that delivery, the app tells me to make my way back to the zone center and wait to repeat the process.

After another 2 orders I decided to wait around at the adjacent zone center to mine. The Camberwell centre is on an industrial estate where Deliveroo has set up a collection of ‘Rooboxes’. These are mobile huts, which each contain a kitchen and 2-3 staff who only produce food for us to deliver – a customer cannot walk up and order directly. In appearance it is very like a hipster pop-up street food market, except the hipsters are geographically located elsewhere, in their home or office, and at the other end of the app. Here we collect food from Gourmet Burger Kitchen, Motu Indian Kitchen, Crust Bros or whoever else is set up there at that time. It all runs through a central distribution office (also a temporary structure) where Deliveroo staff call out your name and give you the food.

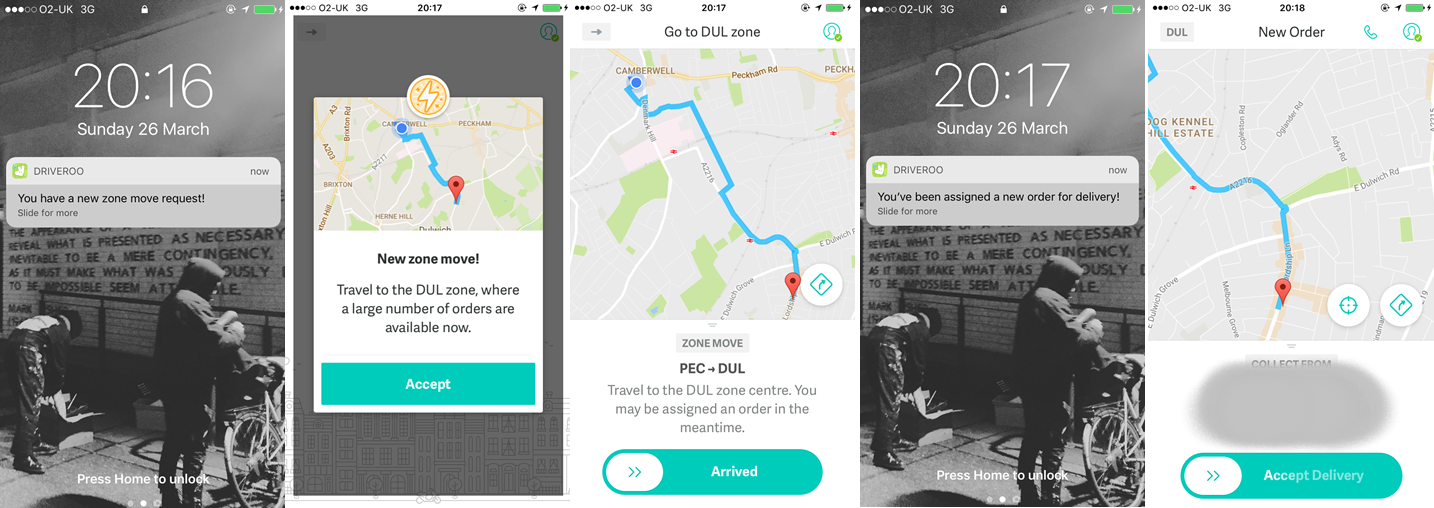

I sometimes prefer waiting at this zone center because they have an indoor break room with chairs and a free coffee machine, as well as some toilets. It is quite different from the other assigned meeting points across the city, often just a place for bicycles and mopeds to be parked up. It is also close to a couple of restaurants which are in my zone, so I do not need to worry about missing orders or being told off and, if my zone goes quiet, I usually get reassigned to Camberwell anyway. However, instead of being reassigned to Camberwell, I was reassigned to Dulwich. Like orders, the app only offers the option to “accept” a zone move. Again, me and the other riders have our theories about what we can get away with, and we all occasionally sit out the 3 minutes of notifications every few seconds until the request is passed onto another rider. I start heading out to the Dulwich centre over Champion Hill (a hill in between a lot of restaurants and customers, in what would otherwise be a pretty flat zone) and within a minute I am given a new order. The order took no more than a minute to complete as the customer was less than 200 meters from the restaurant.

The next order is for Franco Manca, a trendy pizza chain only a few doors down from the last restaurant. It is another stacked order so I have to wait for both before I can see where I am meant to be going. There are a few other riders here already waiting, who say it is taking a long time for anything to be prepared. We chat about the weather, our bikes, our other jobs, how long we’ve been doing Deliveroo, the good and bad about it, and of course the wages, including how most of us would not bother with it if they changed us to a piece rate. This is the basic conversation that most of us have if we meet each other for the first time, but in your own zone you build friendships and find other points of common interest, strengthened through WhatsApp contact.

I was waiting here for over 40 minutes, which means Deliveroo has missed its target of delivering within 30 minutes of the original order. One of the orders had already been given to me after about half an hour, and was just getting cold in my bag while I waited for the other. I got a phone call from Deliveroo Rider Support, saying that the customer had rang up customer services to ask where their pizza was. They wanted to know why I had not left, they could see on the map that I had been outside this restaurant, stationary, for too long. I explained that there was nothing I could do, it is the restaurant’s problem and I would do the best I could. When I got the second order, I delivered them both without any problems, and let the person with the cold pizza know that if they complained to Deliveroo they would either get a full refund, or replacement order and get to keep what I had just delivered. All the riders I have spoken to about this specific issue said they do the same. We all know that Deliveroo can sort out free food and we are happy to share that knowledge with the customers – just so long as it is not our personal fault for the food being late.

The restaurant’s delay in preparing the food meant I was already past the end of my shift. I continued to work until 35 minutes after my shift ended, assuming that I would probably still be being paid my hourly wage as well as deliveries. Technically, I could have logged out by phoning the Rider Support line, asking to be unassigned, then they could reassign it to someone else and I would leave the pizzas with the restaurant. However, the line gets jammed at 9:30pm as so many people are doing this, so being on hold takes just as long as delivering the food. And if you deliver the food you get the pay, so it is just not worth the hassle. A far from seamless interaction with the platform. Finishing shifts on time is rarely possible. There have to be almost no orders going through, as the closer you get to 9:30 the more people log off, meaning fewer people to take orders. This means you can log out early and lose money, or risk waiting and possibly be assigned more orders. I usually decide to stay on the app unless I’m exhausted, as by this time I am happy enough to be on the bike, thinking about how each extra pound makes things a bit easier.

Part II

Illusion of Freedom

Working for Deliveroo on a bike presents a comforting illusion of freedom. You are on a bike, you can pick your route, and to a certain degree you go at your own pace. However, this comforting illusion is regularly unravelled. Sometimes a whole shift can be unremittingly shit. In the winter you have entire weeks in the snow, wind, or rain when the weather is -3 to 3 degrees Celsius 13 and all your shifts are in the dark. Your hands, feet, and face are numbingly cold and your body is sweating from your clothing and the exercise, but you still have to be aware of ice and wet leaves on the road and the bad judgements of other road users who are also inhibited by the conditions. In better weather, it is easy to memorize your route, and drift off into a daydream, only awoken as you get to the house though sometimes after the door has shut and the customer has taken their food, and often hours will pass and the daydream will go outside of the cognitive threshold of the repetitive, rhythmic movements towards the next point in a journey without any coherent direction other than its next point. This is analogous to Sadie Plant’s description of the way the digital worker “has only half a mind on the task,” that “she hears, but isn’t listening. She sees, but she does not watch. Pattern recognition without consciousness.” 14 The experience of a routine activity becoming near-automatic – especially those as risky as driving or biking in London – can be quite scary before reinforcing the estrangement we feel from these activities.

This daydream offers an interesting insight into how capital production is facilitated through the synthesis of technology, labor, and space. The fact that this synthesis occurs is not surprising, as the role of digitized routing is a way of augmenting the two dimensional “God’s eye-view” into our own visual interpretation of places. This “view from above is a perfect metonymy for a more general verticalization of class relations in the context of an intensified class war from above,” as the “proxy perspective that projects stability, safety and extreme mastery” 15 and, in the case of Deliveroo, is synthesized with the “eye which is dislodged from the realm of optics and made into an intermediary element of a circuit whose end result is always a motor response of the body to electronic solicitation.” 16 The eye becomes an “appendage of the machine,” in which sight is extended through the smartphone, whilst the bicycle mechanically extends the legs. 17 This form of vision is only novel in the sense that the required live cartography is accessible enough that precarious workers can be augmented with it, and it is cost effective as little investment is needed from capital (delivery platforms rarely, if ever, supply the necessary smartphone).

If we consider that our “relation to the world is essentially artificial, technical” then “each human world is a configuration of techniques.” 18 Technology “only stands out in two circumstances: invention and ‘breakdown.’ It’s only when we are present at a discovery or when a familiar element is lacking, or breaks, or stops functioning, that the illusion of living in a natural world gives way in the face of contrary evidence.” 19 This notion has multiple implications: in the broader sense, the interest in the technology of Deliveroo, and its relation to capital stems from the fact that it appears as an invention, a novel recombination of existing sectors (logistics, apps, smartphones, flexible work), and on the other hand, in the subjectively particular sense, in that this confluence of techniques “configures a world” which is materialized through these techniques. 20 The worker intermittently exists in a flow outside of a conscious interpretation of the empirical surroundings – until a car pulls out unexpectedly, an address does not match up, or the servers crash. It is also an invention that regularly breaks down, for the user, the worker and, and consequently, for the company.

When the servers go down, a compensatory wage is supplied for the period of outage; however, under no other circumstances is this offered to workers. Of course issues also arise from mechanical failures for both vehicles and phones, with punctures and flat batteries being the most common for me as a bike rider. On top of this, I regularly had schedule clashes between Deliveroo and other jobs that I needed to prioritize. Moped drivers also manage a real risk of theft. Although I’ve had a couple of teenagers try to take my phone on a shift and I had two workmates who had their bikes stolen, the threat and consequences are far more serious for motorcyclists, who are likely to have more valuable vehicles and to have Deliveroo as their primary source of income. The extent of this problem has lead to drivers forming self-defense groups in order to confront and attack thieves, something which cyclists have not had to do as of yet. These problems disrupt the flow of the work, yet remain hidden behind the facade of the platform.

Despite these breakdowns, the illusion of freedom sets this kind of work apart from other precarious options. Unlike working in a call center or other service work, there is no demand to smile or use your emotions while delivering food. There is not the imposed “demands on the delivery and maintenance of packages of affects” found with selling in call centers, 21 so there is the cognitive space to have those kinds of daydreams. If you are lucky enough to get a tip, it is either set when the customer makes the order or handed over with the food in a brief exchange – sometimes just a hand from through the half open door – it is determined before the worker arrives at the door. The other notable difference with other kinds of work is the absence of supervisors or managers roaming the workplace and surveilling workers directly. The only contact with Deliveroo is mediated through the app or meeting other workers at the designated waiting points. This means being away from the supervisory gaze, not feeling the physical pressure to modulate behavior beyond meeting the time requirements of the platform.

Vectors of Authority

The closest I get to interacting with management on a day to day basis was outside Franco Manca when I received the phone call to check up on me. Even then, it was a phone call from a call center worker rather than a supervisor or a manager. What it shows, though, is the conglomeration of managerial techniques that they have available: platform user (customer, restaurant, or rider) feedback, and an algorithmically sorted accumulation of data. Deliveroo knows exactly when and where I am at all times I am logged into the app. This means that when discipline is applied, as in the case above, it is operating along vectors of authority. The term vector is not meant in any kind of metaphysical sense: the GPS tracking situates the rider in a four meter area through signals which travel in lines directly from terra firma to satellites. The tracking produces not just current location, but also distance covered and the time it has taken. These three factors produce the bulk of the data necessary for the management of each rider, by allowing rankings according to efficiency. Deliveroo maintains that they do not prioritize any riders over others, claiming that the rider is selected for each job according to how close they are to the restaurant. However, this seems incongruous to the technological rationality that they would want anything other than predictable efficiency. It seems even more superfluous when the realizable value in the data that is automatically collected might not be used. In practice, me and my colleagues are very aware that those who are faster get more orders, regardless of how far they are from each collection point.

Although drone warfare is radically different to Deliveroo in a number of obvious ways, it nevertheless deploys similar techniques. Therefore it is interesting to contrast Gregoire Chamayou’s analysis that:

In contemporary doctrines of aerial power, operational space is no longer regarded as a homogenous and continuous area. It has become “a dynamic mosaic where insurgent objectives and tactics may vary by neighborhood.” We should see it instead as a patchwork of squares of color, each of which corresponds to specific rules of engagement. But those squares are also, and above all, cubes. 22

The difference is that optic is not oriented towards a contested territory or groups of people, but an individuated practice of power from above. There is no need for cubes when a phone in the pocket indicates all necessary information. To reiterate, this is not to say that the material outcomes of these operations are in any way comparable, only the verticality of perspective which reduces an individual’s movement and time into social profiles, where “activity becomes an alternative to identity” are. 23 What is shared is a common faith in quantitative data, a decision making process in based in pure positivism. Both Deliveroo and drone strikes rely upon networks of GPS satellites, receiving information only available through the military-industrial complex.

The Deliveroo platform - enabled by GPS and smartphone apps - provides a real-time “God’s eye-view” of workers currently logged in. This produces a management perspective that is similar to a real-time strategy videogame – watching the city from directly above, viewing the abstracted “units” as they move around the terrain, and displaying live data flows of various kinds. However, unlike the power fantasy of the videogame, this perspective does not translate into the omnipotent ability to direct “units” through mouse clicks. It is therefore possible to capture this as a kind of “electronic panopticon” 24 – or perhaps even an “algorithmic panopticon” 25 – a dispersed center that can automatically collect and collate quantitative data from which, officially at least, workers cannot escape. However, unlike the architectural design of the panopticon, the supervisory role no longer has a physical manifestation. Instead, the worker is corralled with weekly emails that state whether or not they are meeting their targets. This synthesis of panopticism and Taylorism is exemplary of the individuation of capital production present in fully electronically mediated work, complete with time stamps and geolocations.

The Politics of Knowledge

Against this exhaustive data collection of data and the omnipresent God’s-eye viewpoint, this project began as a way to think about and discuss gig economy work from the perspective of someone working at Deliveroo. We have presented here our initial attempt at an inquiry at Deliveroo. As a collaboration between a driver and a researcher, we have tried to explore the labor process and how it is experienced from the perspective of someone actually delivering food across London on the platform.

As can be seen in the Figures, the minimum amount of data is shared with the driver at each point along the labor process. The customer knows even less within this interaction, only notified of the order acceptance and when the delivery has arrived. Between the two, the platform mediates access to the data – for the latter is unlikely to want to know more (after all the appeal of these platforms is quick and easy delivery of food), while for the former trying to gain more access to the data (not only from the platform more generally, but also their own) is extremely difficult. Each order, communication, journey, delivery, timing, GPS position, and so on is tracked and collated. This kind of data is created by the movement and interaction of people around the city, but its capture remains proprietary. These data sets are becoming an important resource for training machine learning algorithms, seeking to displace (at least in part) human labor.

For the driver to understand their own data trail, it is possible to reconstruct parts of it from fragments of communication from Deliveroo, including the receipts for each delivery. The metrics by which the platform assesses performance are never made clear. Either the driver meets the targets or not, with no indication of the margins of success or failure. In addition to these methods, self-tracking technologies have been used to trace the routes around the city, a collection of data through another means that the platform already holds. In this way the inquiry here is also a contestation over knowledge of work at Deliveroo. The use of these technologies still produces a top down perspective with roadmaps. It is possible to make calculations, but these are still the calculations that are of most interest to capital. Like the RTS game perspective, it is individual and controlling, a view from capital onto workers. This raises questions – beyond the scope of the article here and the tools used at present – about how else the experience of work could be perceived and mapped.

Layers as meeting points

When looking at the maps, it can be seen that the lines are unevenly distributed, that in many places there are considerably more than in others. The importance of this is fairly straightforward. It shows that there are routes which are more and less familiar to myself and to other riders. Our relation to these spaces is materialized each time we are in them. Together, as we work, we produce a topographical layer, where we converge intermittently. The uniform, which has become a ubiquitous part of London’s landscape, provides a double function. In one direction it serves to translate the worker into an aspect of the commodified food product: Deliveroo and its riders are marketed as being synonymous with the food it delivers. But in the other, it allows for reciprocal recognition between co-workers, where we can nod or wave as we pass, or chat during waiting periods. These factors, among others, operate in such a way that a social field is produced. In the emerging literature, there is an all too often gesture towards the gig-economy as being the highest point of alienation, 26 mainly trying to moralize against the use of such apps and services as opposed to providing space for a nuanced interpretation of it, or even of what it is. If instead we attempt a geographically sensitive understanding of Deliveroo, then we see how localities are formed “as a social phenomenon, not so much a singular or specific place, but more as a densely acquired network of familiarity that spans across people and places.” 27

Drawing back from the individual maps, it is possible to take in the bigger picture of how Deliveroo work is conducted in and through the environment of London. The risk with this kind of work is to overemphasize the digital dimension, focusing on the novel management techniques and methods of technological surveillance.

A broader recognition must be made here: that Deliveroo is contextualized socially and spatially in the cities that it operates in. From my interaction with them in London, I have seen how they occupy spaces that are temporary or rent-free, from kitchens in temporary buildings to publicly maintained roads as logistical routes. The coalition between capital and the state has effectively sanctioned and legitimized so much of the reality of city dwelling. High rents and Right-to-Buy, Buy-to-Let and property speculation, poor housing regulations and underfunded councils, inflated costs of living and long working hours – these things are neither legitimate nor natural, they are produced by the amalgamated tendencies of “austerity” and neoliberalism – both of which function within the paradigm of capital accumulation. And such conditions are instrumental to recruiting labor-power for Deliveroo.

Steve Hanson has written on the “the dialectics of working and not working” where he dissolves “the fake, state barrier between official and unofficial economic activity.” 28 Through his own ethnographic work of an English town bombarded by austerity he unpacks how “on-and-off” work and “getting-by” are related to the “precariousness of everyday life.” 29 The dissolution of the binary between employed/unemployed allows us to recognize that “paradigms and people are dialectically connected, they all contain each other as part of a wider assemblage.” 30 Austerity and underlying economic conditions combine to produce unofficial economies as people try to make ends meet beyond regular Fordist employment, which, over the last few years, the ever innovative gig-economy has tended towards formalizing and monopolizing each sector that presents itself. The neoliberal project of creating individuated entrepreneurs is an “ideal type” for the gig-economy worker. A self-contained economic unit, an independent biography creating their own story. The container as “a dumb, indifferent, interchangeable materialisation of capital’s abstract circulation.” 31 Hanson suggests that this “‘containerization’ can be thought of as a metaphor, but only if one inverts it, because when metal boxes began containing objects, they did so to distribute them more widely and quickly … capitalism deterritorializes in order to territorialize, but it does not do so to trap people or objects in one place or any landscape, all of which are becoming steam.” 32 Legally self-employed micro-entrepreneurs are in a way the negative of the jet-set executive, a person who is forever in transit, virtually mobile, closing a deal and moving on. Two sides of the same coin.

Deliveroo could only emerge under certain economic and social conditions, just as much as it will only survive in cities where the relationship of production can be reproduced. This means that flexible, “extra” work must be necessary to a large enough portion of the population, that wages within the capitalist centers are significantly higher than in “peripheral regions” and that the necessity of “getting-by” is economically and disciplinarily enforced. It is in these oppressive feedback loops where the producer-consumer dialectic is folded upon itself that companies such as Deliveroo, AirBnB, and Uber can proliferate. As many have noted, they are not produced by “technological” feats: “the form innovation takes within capitalism is as the continual simulation of the new, while existing relations of power and control remain effectively the same.” 33 These new arrivals are low-asset, lightweight corporations which are well suited to the slow-growth recession economy. 34 They shouldn’t be critiqued in isolation, as they are not singular entities. After all, they are continuous with the historical and geographical domains they parasitically root themselves in – whether its bedrooms, hired cars or our streets. We have seen how in Brighton one of the demands from the Deliveroo workers’ protests was to immediately cease recruitment. This was because the reality of piece-rate work and a workforce greater than work available created an oversaturated region where riders often would work entire days for a couple of pounds. 35

It must be remembered too, that Deliveroo is in no way producing absolute “places” or totalities. Like other platforms, it is superimposed into localities that are familiar and lived-in. They are interrelated to the “unlimited multiplicity or unaccountable set of social spaces which refer to generically as ‘social space.’” 36 The intention behind reiterating the interaction between this work, sector and locality is simply that if we metaphysically enclose Deliveroo as a subject in itself then we cannot unfold its ambiguous continuities. Occasionally when I’m at the Camberwell site (see above), I will see an Ocado truck pull up to deliver ingredients to the “restaurants”. Ocado is an on-the-day, food distribution company that operates from warehouses, with an app and a website creating a customer interface without a shopfront. The operational similarity of Ocado and Deliveroo shows how localities in logistics operate on different on different scales which are layered between and on top of one another, and how the concealing of labor is consistent in both levels.

When working, many other riders have conversations through their headphones, or with their phone jammed between the side of their head and the padding of their helmet. The conversations I overheard glimpses of what were in many different languages presumably to other parts of the city, country or world – in short, to other places. Whilst I and others daydream, others continue to make use of their vocal faculties to voluntarily maintain their own social contemporaneity. Here, we see other possibilities of the fragmentation of experiences, where the worker is simultaneously occupying social space here and there, deterritorialized and diffuse. Few jobs offer this kind of freedom to communicate. For example, both authors’ experience of working in call centers offered the opposite of this – in that you do not have the possibility to daydream or talk freely on shift, but also in the periods outside of work conversation can be difficult or intolerable. 37 This aspect of Deliveroo is an example of how workers operate beyond the immediate locality and beyond the surveillance of supervisors, in ways which aren’t necessarily counterproductive and are therefore beyond the managerial field of vision.

Conclusion

The social and spatial qualities of Deliveroo means that a topographical layer is always in a process of becoming, where associations and familiarities with the terrain, riders, and restaurant workers are formed. These interactions can provide rich and pleasant experiences, and the work is often enjoyable, as is the company of other workers. The ability to miss some shifts without the fear of losing the job is a truly valuable aspect. In the words of IWGB’s Jason Moyer-Lee: “flexibility that works for the worker is a marvellous thing. What we do say is that these companies need to abide by the law. Just because some of their workers have flexible work arrangements, that doesn’t mean you can deny them basic rights. 38 We could not agree more. The assumption that flexible work is categorically incongruous with financial stability is a fallacy. Being able to legitimately refuse work is a cause worth fighting for in the courts, in parliament, in streets, and most importantly in the workplace.

A strategic approach to pursuing workers’ rights in the gig economy is a necessity. For the first time in many years we have a meaningful socialist opposition in the UK, with parliamentary members like John McDonnell taking a serious interest in precarious workers’ rights. In recent months, the Labour party look like they have an increasingly viable chance of entering into government. The courts in the UK have already confirmed ‘worker’ status over that of ‘self-employed’ to many of the Doctors Laboratory, CitySprint and Uber workers. 39 Ultimately, workers must be able to take collective action, and the proof that this is possible is still fresh in many drivers and riders memories. The election of a Labour government or the favorable ruling of a court cannot deliver counter-power in the workplace. It is therefore important to remember that this began with a non-unionized wildcat strike of workers from around the world which gained international recognition, a crowdfunded strike fund of £10,000 within the week long dispute, and most importantly: a defeat for management. It is only when workers are at the forefront of the struggles that we can demand and win the conditions we desire.

At Deliveroo one difficulty is knowing what is being fought against. Earlier I noted that many of the rules presented to riders are through implication, and that we often have to rely on experience, intuition, and guesswork to navigate each shift – and to also keep the job over a period of time. For example, in the time it has taken to write this piece, Deliveroo has already changed its rules so that uniform is no longer necessary, removing the equipment deposit scheme, that the piece rate is now opt-in for most London zones, and have relaxed restrictions on signing up for shifts. A lot of these changes seem to be performative gestures to appease the ongoing court case, yet they still have real consequences in reducing the possibility or effectiveness of collective action. Despite this, we can look to recent history for reason to be optimistic. A strike by UberEats workers in August 2016 had many Deliveroo riders striking in solidarity – a phenomena consistent with the strike action taken in Bordeaux in March 2017. This optimism is based on the critical understanding of insurrectionary behavior as:

…something that is constituted here [that] resonates with the shock wave emitted by something constituted over there … not like a plague or forest fire which spreads from place to place after an initial spark. It rather takes the shape of music, whose focal points, though dispersed in time and space, succeed in imposing the rhythm of their own vibrations, always taking on more density. 40

As the intensity of capitals’ occupation of everyday life 41 through the “gig-economy” and its contestations of space progress, so too do the rhythms of defiance fall into new synchronicities. What we could be seeing here is the opportunity to converge industrial action with social strikes. Facility was involved in one of the University rent strikes in London of 2016, which spread from UCL to three other universities in the city. 42 The demands put forward there for safe and affordable housing are synonymous with the demands for living wages and job security at Deliveroo.

Guy Debord wrote that “self proclaimed democratic society seems to be generally accepted as the realisation of a fragile perfection … it must no longer be open to attacks, being fragile; and indeed it is no longer open to attack, being perfect as no other society before it. It is a fragile society because it has great difficulty managing its dangerous technical expansion.” 43 If we apply this criticism specifically to Deliveroo, and platform capitalism more generally, then we can see how they legitimize themselves by appearing to collapse space into seamless perfection, therefore obscuring labor processes out of sight. Marx’s famous claim that capitalism requires the “annihilation of space by time” 44 is abundantly clear in Deliveroo’s technical rationality. A distance becomes absolute and binary, complete or incomplete, delivered or not delivered – the delivery as a commodity in itself, as something to be produced by one and consumed by another. However, the strikes reveal the fragility of this “perfection”; the movement from dots on screens to bodies in the streets simultaneously alters the visibility of the worker, removing them from the “God’s eye-view” of the commodity, whilst rupturing the seamless, hyperreal space of the city.

References

| ↑1 | Deliveroo divides the city into various zones, each with a meeting point at the zone center. See Figure 2. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Independent workers Union of Great Britain, https://iwgb.org.uk/ |

| ↑3 | Rebel Roo #5 (March 4th, 2017) available here: http://www.weareplanc.org/blog/rebel-roo-5/ |

| ↑4 | Sarah O’Connor, “When your boss is an algorithm,” Financial Times, (September 8th, 2016) available at: https://www.ft.com/content/88fdc58e-754f-11e6-b60a-de4532d5ea35 |

| ↑5 | Crunchbase, “Deliveroo,” (2017), Accessed, July 20th, 2017, available at: https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/deliveroo#/entity |

| ↑6 | Deliveroo, “FAQ” (2017) Available at: https://deliveroo.co.uk/faq |

| ↑7 | Trebor Scholz, “Digital black box labor,” P2PF Wiki, (2015), available at: http://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Digital_Black_Box_Labor |

| ↑8 | Frank Pasquale, The Black Box Society: The secret algorithms that control money and information, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015). |

| ↑9 | Asad Haider and Salar Mohandesi, “Workers’ Inquiry: A Genealogy,” Viewpoint Magazine, issue 3 (2013). |

| ↑10 | Acas, “Zero Hours Contacts,” (2017), available here: http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=4468 |

| ↑11 | A Levels are a non-compulsory qualification offered either in schools at sixth form or a further education college. They are a prerequisite qualification for most university degree courses in the UK. |

| ↑12 | This map was intended to represent the center point (cyclist icon), login zone (circle surrounding) and the total delivery area (purple). However, this map was already outdated when I received it in July 2016. |

| ↑13 | Around 27 to 37 degrees Fahrenheit. |

| ↑14 | Sadie Plant, Zeros + Ones: Digital Women + The New Technoculture, (London: Fourth Estate, 1998), 129. |

| ↑15 | Hito Steyerl, “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,” e-flux, 24 (2011). |

| ↑16 | Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, (London: Verso, 2014), 76. |

| ↑17 | Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, (1848) available online: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm |

| ↑18 | The Invisible Committee, To our friends, (London: MIT Press, 2014), 122. |

| ↑19 | Ibid, 122 emphasis added. |

| ↑20 | Ibid, 122. |

| ↑21 | Jamie Woodcock, Working the Phones: Control and Resistance in Call Centres, (London: Pluto, 2017), 53. |

| ↑22 | Gregoire Chamayou, Drone Theory, (London: Penguin, 2015), 54. |

| ↑23 | Ibid, 48. |

| ↑24 | Sue Fernie and David Metcalf, (Not) Hanging on the Telephone: Payment Systems in the New Sweatshops, (Centre for Economic Performance: London School of Economics, 1997), 3. |

| ↑25 | Jamie Woodcock, “Automate this! delivering resistance in the gig economy,” Mute, (March 10th, 2017), available here: http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/automate-delivering-resistance-gig-economy |

| ↑26 | See, for example: Patricia Leighton, “Professional self-employment, new power and the sharing economy: Some cautionary tales from Uber,” Journal of Management & Organization, vol. 22, no. 6, (2016), 859-874; Trebor Scholz, Uberworked and underpaid, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017). |

| ↑27 | Suzanne Hall, City, Street and Citizen: The Measure of the Ordinary, (London: Routledge, 2012), 129. |

| ↑28 | Steve Hanson, Small Towns, Austere Times: The Dialectics of Deracinated Localism, (Alresford, Hants: Zero Books, 2014), 68, 69. |

| ↑29 | Ibid, 73. |

| ↑30 | Ibid, 69. |

| ↑31 | Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle, Cartographies of the Absolute, (Alresford, Hants: Zero Books, 2015), 196. |

| ↑32 | Hanson, Small Towns, Austere Times (2014), 153. |

| ↑33 | Crary, 24/7 (2014), 40. |

| ↑34 | Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017). |

| ↑35 | Callum Cant, “ I’m a Deliveroo rider. Collective action is the only way we’ll get a fair deal,” The Guardian (March 31st, 2017), available here: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/mar/31/deliveroo-organising-wages-conditions-gig-economy |

| ↑36 | Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 86. |

| ↑37 | Woodcock, Working the Phones (2017). |

| ↑38 | Jason Moyer-Lee, “What everyone assumes about rights in the gig economy is wrong”, The Guardian, (March 22nd, 2017), available here: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/mar/22/rights-gig-economy-self-employed-worker |

| ↑39 | See: https://iwgbclb.wordpress.com/ |

| ↑40 | The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection, (London: MIT Press, 2009), 12-12. |

| ↑41 | Understanding ‘everyday life’ as a political territory, where Lefebvre (1991, 228) sees “the only genuine, profound human changes [as being] those which cut into this substance and make their mark on it.” |

| ↑42 | Diane Taylor, “University students across London take part in rent strike”, The Guardian, (May 6th, 2016), available here: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/may/09/rent-strike-students-ucl-london-threat-to-education-access |

| ↑43 | Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, (London: Verso, 1998), 21. |

| ↑44 | Karl Marx, Grundrisse, (1857) available online: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/ch10.htm |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine