In September 1931, the League Against Imperialism and for National Independence (LAI), 1927–1937, a sympathizing organization against colonial oppression connected to the Communist International (Comintern; Third International, 1919–1943), published the theoretical organ The Anti-Imperialist Review. Bekar Ferdi (1890–?; real name: Mechnet Schafik), a leading figure of the Turkish communist movement and secretary of the LAI, was one the contributors. In the article “Why We Appear” Ferdi pointed out the purpose of the review and declared that with it, the LAI aimed at capturing the contemporary scope and nature of global anti-imperialism. Explaining why the review had appeared at this particular moment, Ferdi stated: “The journal will provide a weapon for rallying forces to the League, for extending and developing the front of the anti-imperialist struggle, for spreading and popularizing the slogans of the League and consolidating and unifying the ranks of those fighting for the overthrow of imperialism. It will be a powerful force.” Ferdi declared in conclusion that the review would aid the work of building up “an organisational concentration point for all the forces which are ready to struggle without compromise and with revolutionary determination against the Versailles system and for a new just organisation of Europe on the basis of the complete right to self-determination.”

While Ferdi had outlined the aim of The Anti-Imperialist Review to function as “a weapon for rallying forces” to the LAI, what did the LAI actually expect to convey by publishing a theoretical organ on anti-imperialism? And why was The Anti-Imperialist Review considered to be exceptionally relevant for the LAI in 1931?

The LAI was established on the direct instructions of the Comintern as an international sympathizing organization, and was officially inaugurated at the “First International Congress against Colonialism and Imperialism” in Brussels on February 10–13, 1927. The German communist weekly pictorial Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung described this event as “the congress for the oppressed billions,” and in a long-term perspective, the League framed the nostalgic vision of anti-imperialism as portrayed and introduced in Achmed Sukarno’s opening address at the “Afro-Asian Conference” in Bandung, Indonesia, April 1955. 1

The history of the LAI can be concisely summarized: it begins with the success and euphoria of the Brussels congress of 1927, only to end in 1937 after being engulfed by the success of the Popular Front policy and the growth of the anti-fascist movement in Europe. As the Communist Party of Great Britain launched the “Unity Campaign” as a means to create a stronger alliance with the Popular Front, the LAI – its operative center now in London after several years in Berlin, then Paris – succumbed to the pressures of being a “banned organization,” and in May 1937 it was quietly dissolved. 2 Within the period of ten years, the LAI underwent numerous organizational changes, ideological alterations, and geographical transfers, yielding the reputation of the organization as a concerted source of inspiration for the decolonization movements in the post-war period. A vital part of the LAI’s legacy, then, is the scope and content of its propaganda against colonialism and imperialism.

Today, forums of resistance and counter-narratives are mostly located across the political landscape of social media. And yet, evident difficulties remain in relaying information about ongoing struggles, fortifying activist networks, and providing theoretical bases for internationalism in practice. Several clues and models for strengthening solidarity in resistance against oppression, colonialism, and imperialism are to be found in the study of radical and subversive publications, anti-imperialist campaigns, and demonstrations as they surfaced in the first decades of the 20th century. The LAI’s theoretical organ The Anti-Imperialist Review and its editorial history represent a constituent source of militant reportage on global anti-imperialism between the two World Wars, a rigorous effort to construct a conceptual framework for the international communist movement’s approach to colonialism and imperialism as political topics, and how these phenomena were articulated within the broader international relations of force. The dead-ends and rapid, often contradictory, ideological and political shifts the LAI had to navigate also point to the insurmountable problems of the anti-imperialist practice of Comintern-linked organizations.

1931: The LAI at a Crossroads

The LAI was active in developing several anti-imperialist propaganda campaigns over the course of 1931. It coordinated political work around the anti-imperial “Counter-Exhibition” in Paris, a project undertaken in response to the “Imperial Colonial Exhibition” in Vincennes the same year. Located on the outskirts of the French capital, this six-month long affair was a macabre display of colonial might, and was effectively depicted and denounced by the League as a microcosm of the French empire. Further, the LAI took strides in advancing an international protest campaign against the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in the fall of 1931; collaborating with the communist mass organization International Red Aid in forging transnational contacts in support of the eight African-American young men in the Scottsboro trial in the United States, who were wrongly accused of having raped two young white women. At the same time, serious social, political, and economic crises rapidly shot up across the globe: the collapse of the world economy in the summer of 1931; the rise of fascism across Europe and the strengthening of Nazism in Germany; and the societal consequences of Stalinization of the Soviet Union through aggressive collectivization and industrialization.

The LAI had to confront and mitigate internal and external problems in this explosive conjuncture, and by 1931 it was desperately seeking new ways and means to renew itself as an international sympathizing organization focused on strengthening connections between anti-colonial struggles and being a petitioner against oppression. The revival of The Anti-Imperialist Review – an initiative which the LAI had begun in 1928, only to cease publication after a single issue – stood out as one of few existing endeavors for the LAI to articulate a strong counter-narrative against colonialism and imperialism, and which could attract forces of support and solidarity. But the most crucial factor in this context was the Comintern, the organizational infrastructure that defined the activities and initiatives of the LAI. Without the consent or assistance originating from Comintern headquarters in Moscow to the LAI’s administrative center and international hub – the International Secretariat in Berlin, which oversaw the second edition of The Anti-Imperialist Review – none of the above was achievable or possible to carry out in practice. This was a one-way relationship, determined through the Comintern’s willingness to extend material assistance.

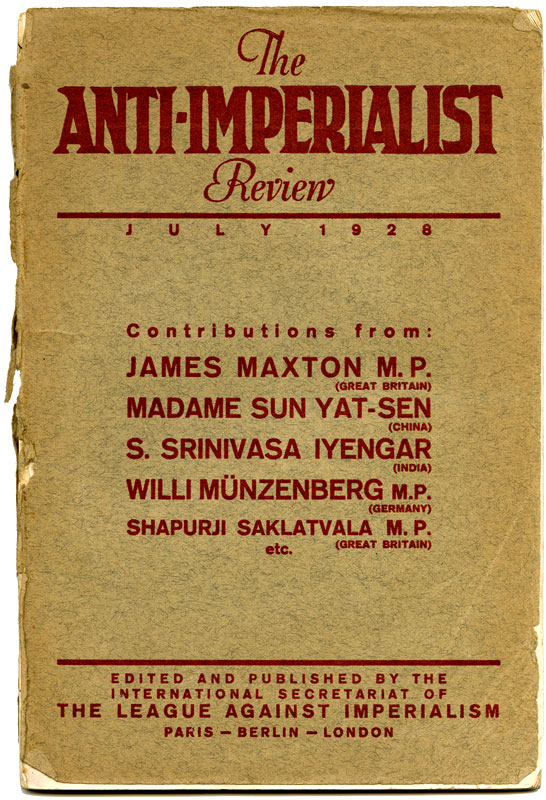

The revival and publication of The Anti-Imperialist Review in 1931 served several strategic purposes. The initial version of the review, which had appeared in July 1928 served a similar purpose as the one introduced in 1931, i.e., to function as a theoretical organ and tribune of global struggles. According to the “Foreword,” authored by the LAI’s chairman, the British socialist and leader of the Independent Labour Party James Maxton, conceded that it was with “great satisfaction” that the review would hopefully be “helping toward the liberation of the world’s workers.” Further on in same the issue, the LAI’s General Secretary and leader of the proletarian mass organization the Workers’ International Relief, the German communist Willi Münzenberg (1889–1940) described how “the echo of the Brussels Congress” had generated “very wide attention” on the LAI, and the review would aid in galvanizing the essential “cooperation of all anti-imperialist forces” on a global scale. 3 However, nothing of the above ever materialized, and the first issue was not followed by a second one in 1928. But it is important to respond to Sean McMeekin’s erroneous conclusion in his 2003 biography of Münzenberg, The Red Millionaire, that the sudden disappearance of The Anti-Imperialist Review in 1929 led to the dissolution of the LAI the same year, a puzzling observation that simply does not hold up. 4 The political and organizational history is much more complex and deserves careful attention.

As the international communist movement embarked upon its drastic “turn to the left” with the ceremonial introduction of the Comintern’s “new line” at the Sixth International Comintern Congress in Moscow in August 1928, which advocated no political collaborations or affiliations outside of the communist movement, and later in 1929 acknowledged by the Comintern as the policy of “class against class,” this essentially put a halt to the LAI’s ambitions of publishing a theoretical organ on colonialism and imperialism. The Comintern’s “new line” had immediate consequences on the organizational preparations and political results of the LAI’s “Second International Congress against Colonialism and Imperialism” in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, on July 21–27, 1929, which saw communist delegates deliberately engaging the non-communist delegates in callous debates. As the former went on the attack and demanded the LAI to purge itself of “national reformists” and “agents of imperialism,” the latter retreated into either humiliation or silence. Above all, this concretized the practical outcome of the Comintern’s class against class policy as it provided the international communist movement with a new lingua franca on how to imagine itself vis-a-vis ideological counterparts. For the LAI in particular, this experience confirmed that it was next to impossible to even consider the idea of publishing a theoretical organ to a circle of readers outside of the communist movement.

The Frankfurt congress ushered in a period of trial and chaos within the LAI, which largely diminished the organization’s political credibility as an advocate of international anti-imperialism and confirmed the suspicions of the international socialist movement that the LAI was nothing more than a front organization of the Comintern. This time of turbulence questioned the very existence of the organization at all levels and cast the post-Frankfurt LAI into an ideological and organizational divide lasting for about a year. The expulsion of Maxton by British LAI section in September 1929, for example, was motivated by a decision that he “displayed no interest whatever in events of tremendous importance in colonial countries.” 5

This simmering tension dissipated after the Political Commission of the Comintern, an institution that consisted of leading members in the Comintern apparatus in Moscow, approved a plan proposed by the Czechoslovakian communist and LAI secretary Bohumíl Smeral. Smeral had conducted a thorough internal investigation of the LAI, which he presented to the Commission in Moscow on September 13, 1930. He suggested dividing the LAI into two halves. One, the “official” half, would advocate uncompromising agitation against imperialism, and promote the “liberation struggle in the colonial and dependent countries,” “the revolutionary class struggle of the proletariat,” and defend the “building of socialism in the USSR.” The second, unofficial side would posit the LAI as “a relief organization,” and establish transnational relations for the Comintern to gain a foothold in resistance movements and oppositional activity in the colonies. Hence, the LAI was to play the role of intermediary between national liberations movements in the colonies and the Comintern, or as Smeral eloquently described it to the Political Commission: “as an auxiliary organ, acting as a cover, [the LAI] would be connected with the Comintern much more than until now.”

The Political Commission approved of “dividing” the LAI in two halves, promising to secure sufficient funds and provide with political support on a regular level from Moscow to the LAI’s International Secretariat in Berlin. One key element of this work was in getting the LAI to revive The Anti-Imperialist Review, the Political Commission stated, and for it to be circulated in “imperialist metropolises,” such as London, Paris, and New York. This invites comparisons to Münzenberg’s transnational organization, Workers’ International Relief, which predominantly broadcasted its message of proletarian solidarity via various propaganda campaigns and publications. Münzenberg’s publishing company Neuer Deutscher Verlag in Berlin regularly issued Der Rote Aufbau, a theoretical journal that functioned alongside the proletarian mass organization. Yet the LAI did not have a mouthpiece of similar caliber, and with the internal consequences of the crisis connected to the class against class strategy – which in a broader perspective was symptomatic of the Bolshevization and Stalinization of the international communist movement in the 1930s – the LAI had to do anything possible to curb any decisive and lasting negative fallout from Frankfurt congress in 1929. The question of reviving The Anti-Imperialist Review was therefore not only caught up in the maelstrom of international communism; it also reflected the difficulties and possibilities of making the LAI’s anti-imperialist agenda credible again.

“The review will strengthen our work”

In January 1931, the LAI’s International Secretariat felt betrayed by “our major colleagues” at Comintern headquarters in Moscow. Considering the increasingly sectarian behavior and conspiratorial techniques set in motion after the LAI’s crisis in 1929–30, every communication from Berlin to Moscow was compiled and dispatched by the “Komfraktion” [communist fraction] of the International Secretariat. Lacking funds and political directives on how to develop ongoing work, the “Komfraktion” described in a letter to the Comintern’s Eastern Secretariat (the LAI liaison at Comintern headquarters in Moscow) how they were sitting around the office, doing nothing, and “just looked at each other.” 6 Left with a fragile organizational structure after the crisis and its temporary solution in September 1930, one of few options available was to launch propaganda campaigns, with publishing as a crucial site in the broader terrain.

The publications of the LAI’s International Secretariat were considered to be minor successes by the “Komfraktion.” According to a confidential “circular letter” to the Comintern’s Eastern Secretariat in Moscow, the monthly circulation of pamphlets and newspapers had gained attention among reading circles outside of the communist movement. The possible reactivation of The Anti-Imperialist Review was expected to add weight and standing to the publications springing from the LAI’s International Secretariat: for example, the Informationsdienst (Information Service), Pressedienst (Press Service), and the regular translations of news from India had successfully located the Indian national liberation struggle in a European political context. The publication of the German LAI section, Der koloniale Freiheitskampf, had also made serious attempts to propagate an anti-imperialist understanding throughout the country. The LAI’s aim to introduce a nuanced picture of how contemporary colonialism and imperialism looked across the world required a massive amount of material to be written for inclusion in the publications. In turn, the International Secretariat needed to acquire a wide array of books, journals, and papers published internationally. But at the level of outreach, the LAI’s publications released were mostly written and published in the German language. The renewed emphasis on The Anti-Imperialist Review as an English-language journal indicated new directions for organization within specific national situations and vernaculars.

After briefly languishing in the beginning of the year, the discussion over the review restarted with an assessment of the relevant content for the first issue. The LAI subsequently conveyed to the Eastern Secretariat what should be included. The International Secretariat wanted to highlight narratives of colonial countries by publishing “letters from the colonies,” something that would avoid “abstract” and theoretical accounts of the concrete conditions in China, Indochina, Indonesia, and Latin America. Further, to counteract the “Imperial Colonial Exhibition,” scheduled to open in Vincennes in the outskirts of Paris in May, the review should advertise and outline the idea of holding an anti-imperialist “Counter Exhibition” in Paris. The latter text would be written by Ferdi, considering his frequent travels to the French capital and his close relations with the Communist Party of France. Additionally, permanent sections of the review had to include reports from the LAI’s national sections, and from “groups, associations of colonial students and other people in different [imperialist] capitals”; book reviews on colonial questions; and short polemical articles and notes on minor anti-imperial topics. According to the LAI “Komfraktion,” the principal aim of the review would be to strengthen and sustain the LAI’s “organizational work” on an international scale. 7

Content and Shape

The work to compile a comprehensive program for the review entered an intense phase in March. Smeral wrote to Ludwig Magyar (1891–1937), a Hungarian communist and deputy head of the Eastern Secretariat in Moscow, to explain that “the project” with the review was beginning to take shape. Accordingly, the review would begin with a statement on “why it was published, or perhaps a better title is preferred,” along with, on Smeral suggestion, a historical trajectory of the LAI since the Brussels congress in 1927. Next, Clemens Palme Dutt, the British communist and expert on the Indian question, would assess the distinction between “oppressor and the oppressed” using geographical, ethnical, and statistical perspectives, a topic he had discussed at public meetings organized by the British LAI section in London 1930. Experiences of the ongoing Chinese revolution and the anti-imperialist struggle in that country was a central concern, and the Indian revolutionary and LAI International Secretary Virendranath Chattopadhyaya (Chatto, 1880–1937) had been told to write a similar piece on the revolutionary struggle in India. Locating the effects British imperialism and “the treachery of the Labour Party” was crucial in this context, and the secretary of the British LAI section, the socialist Reginald Francis Orlando Bridgeman (1884–1968), would contribute an article on this dilemma. Rounding out the primary articles, Ferdi’s frequent travels between Berlin and Paris constituted the sources for his write-up on the anti-imperialist “Counter-Exhibition” and the “International Colonial Exhibition” in Vincennes in May. Besides these articles, the review would have permanent sections, including “letters from the colonies,” correspondence with concurring associations and groups of a colonial origin and consisting of students and workers in Europe and the United States. The review would also contain a report on the situation and activity of the LAI’s International Secretariat and the national sections; short notes and a “talking space” offering polemics on different topics; and, finally, book reviews on colonial questions. 8

Comparing the general outline of the review in 1931 with the 1928 issue discloses important overlaps. First, every article was going to be written by a communist (except for Bridgeman’s contribution, but even he was the acting secretary of the British LAI section, and therefore entrusted with carrying out the task). Second, it was important to retain a global perspective on colonialism and imperialism. The 1928 issue had included articles on the Chinese revolution and Kuomintang; British imperialism in India and “Dutch imperialist policy” in Indonesia; and an interpretation of the colonial rivalry of Anglo-American imperialism in Africa. 9 Aside from the above, the second version of The Anti-Imperialist Review bore much resemblance to the conceptual disposition of the 1928 issue, with sections devoted to book reviews, documents on the colonial question, and general reports on the international development of the LAI. At Comintern headquarters, however, it was recommended that the LAI should use the review as a means of connecting itself with national revolutionary minority movements in Ukraine, Belorussia, the Balkans, the Alsace region, and Germans in Poland. According to Magyar, this line of activity was one of the LAI’s focal points in 1931. 10

On March 14, 1931, the LAI’s International Secretariat provided Magyar with new information on the bi-monthly publication of “a journal,” explaining how the use of English would enhance anti-imperialist work. However, to ensure the regular publication of the review, the Eastern Secretariat in Moscow had to generate the necessary funding to the International Secretariat. 11 It was always a question of money: this put every enterprise at stake regardless of the actual the work needed to prepare and finalize the review. While Magyar sought to guarantee funding and complete his own article, Dmitri Manuilsky, the Ukrainian communist who was reputed to be Stalin’s “eyes and ears” at Comintern headquarters, promised to write the review’s introduction (which he never did). 12 At the end of March, the general outline of the review was completed, and articles had been ordered from several contributors. 13

“Support a new anti-imperialist journal!”

The International Secretariat proceeded to openly declare the pending publication of the review in May. The secretary of the LAI youth section in Berlin, the Japanese-Danish communist Hans Peter Thögersen (1902–?), sent a circular letter to the national sections in April, asking “everyone to support the struggle against imperialism” by circulating the review, a key task in advancing the anti-imperialist movement. The review was envisioned as an educational instrument and source of information for anyone interested in getting involved in either the LAI or the anti-imperialist movement.

First and foremost, Thögersen explained that the review aimed at publishing “theoretical and general political articles” written by the “best fighters against imperialism.” But to a greater extent than its own cadre, the review depended on the active collaboration from the outside: that is, the readers. This referred to the collection of “original letters from the colonies,” and the coordination of contacts with colonial students and workers living in Europe and the United States. The latter suggested gaining access to networks and ties inaccessible to the International Secretariat in Berlin. 14 Moreover, the request from “the centre” in Berlin to the national sections corroborated one of the LAI’s primary functions: to collect intelligence on anti-colonial activists, information which was promptly dispatched for further assessment at the Eastern Secretariat in Moscow.

Even with all of this preparatory labor, the review was still not ready for publication in May. The primary reason was the reconstitution of the LAI’s Executive Committee at a meeting in Berlin from May 31 to June 2, an event that underscored the severity and predicament of the LAI’s situation. This meeting was held to counteract the organization’s crisis and decline – and thus the review had far greater importance than to recharge the LAI’s activities. Indeed, the Executive Committee gathering indicated a revision of former strategies on “propaganda, organizational and tactical issues” and, as I have shown in my research on the LAI, the reconstitution of the LAI’s primary functioning body at the meeting confirmed the Comintern’s governance of the International Secretariat and the LAI. While the central political issue focused on highlighting the need to connect the anti-imperialist movement with national revolutionary minority movements in Europe, most of the discussions placed the troubled internal situation in the national sections on full display. 15

Apropos the project of the review, Münzenberg informed at the concluding session that it was “absolutely necessary” to publish “a magazine” as soon as possible. Considering the recent internal organizational turmoil and deficiencies of the LAI, the level of activity had, therefore, not been comparable to the political obligations of the organization, and as Münzenberg stated, an increase in “energy and sharpness in these areas” with the publication of The Anti-Imperialist Review “possibly in this year” could realize these ambitions. 16 Once the LAI Executive meeting was over, the “Fractional Bureau of the Executive meeting” summarized the impressions of the event, and while debating on the future publication of The Anti-Imperialist Review, it was recommended that “the regular publication of this journal is one of the main tasks of the International Secretariat,” and the first issue should be “devoted mainly to the LAI’s Executive meeting.” 17 Despite the fact that the internal situation in the aftermath of the LAI Executive meeting was “confused,” Ferdi wrote in a letter to Magyar on July 8 that the International Secretariat was committed in preparing the review and for it to “soon be completely edited,” including translations of articles from German to English. And if all went as planned, it would be published in July. 18

Working Out the Details

The International Secretariat had to hear the final opinion of the Eastern Secretariat at Comintern headquarters before it could publish the first issue. According to the July report on the recent activities of the LAI, the International Secretariat expressed concern about not having received a single article from the Comintern for inclusion in the review. At this stage, it was urgent – mostly in order to capitalize on the results of the LAI Executive meeting in Berlin – to publish the review. The lack of proper “documentary material” hampered the overall work, and as the report noted, it was expected that the Eastern Secretariat would send supplementary material and articles to the International Secretariat in Berlin. 19 Expertise on the “Oriental question,” for instance, was minimal in Berlin, and rather than relying on articles published in the Comintern’s weekly newspaper, the International Press Correspondence (Inprecorr), the LAI wanted access to the large quantities of documentary material kept on file at the Eastern Secretariat’s office in Moscow. Despite its explicit dependence on the consent and material support emanating from Comintern headquarters, the International Secretariat managed to complete a final version of the review. Containing twelve articles altogether, the review would begin with an undisclosed statement written by Ferdi on “why we appear” and a survey on the “decisive stage in the development” of the LAI; an article on the “imperialist sharks and its parasites” authored by the Russian writer Maxim Gorky discussed the decisive role of intellectuals and social democracy in protecting the system of “colonial oppression”; and Magyar’s contribution on the revolutionary movement in China, Indochina, and India. Further texts included a letter of greeting from the “fellow traveller” of communism and French author, Henri Barbusse; Smeral had written two articles, one focusing on the social democratic parties in Europe and their policies regarding colonialism, and a second on the “imperialist politics of Italian fascism”; and Chattopadhyaya had written a short piece on “Nehru’s betrayal.” 20

Nehru had been a driving force in linking together the Indian nationalist movement with the LAI prior to and after the Brussels Congress in 1927. Appointed as member of the LAI Executive, he together with Chatto had created a transnational network that channeled information on what was happening in India back to Europe, and, he convinced the Indian National Congress to provide with funding for the establishment of an “Indian Bureau” at the LAI’s International Secretariat in Berlin, having the bureau target Indian students living in Europe. However, after the Frankfurt Congress in 1929, Nehru was no longer considered as a desired person to be in contact with for the LAI, and by the beginning of 1930, he voluntarily resigned from the organization. For Chatto himself, however, working with the review was one of his last undertakings with the LAI. After having acted as the LAI’s International Secretary since 1928, in 1931 he suddenly found himself suspected of “political dishonesty” by the Comintern, only to receive instructions to travel to Moscow to answer to the accusation. In Berlin, and prior to his departure in September, Chatto translated some of the original articles in German or French to English. 21

The review was not published until September. Whether any objections from the Eastern Secretariat delayed the ambitions of the International Secretariat in Berlin to publish in July is not known. However, it is likely that the combination of uncertainty over personnel questions (Chatto’s role), lack of material for inclusion in the review, and the securing of funds from the Comintern for printing and distribution postponed the process. But the fitful starts and prolonged collective labor paid off: the first issue of the revived Anti-Imperialist Review indeed saw the light of day.

“An accurate reflection of what is taking place in the colonies”

The published version of The Anti-Imperialist Review corresponded almost exactly to the proposed July version. However, some of the names of the contributors had been deliberately concealed: Ferdi’s and Magyar’s articles were noted as authors “F” and “M,” while others had anonymous authors. Some articles were added, like Clemens Palme Dutt’s text “The Flood Catastrophe in China,” while Chatto’s article on Nehru was excluded. A promising transnational dimension surfaced in a section on the “Anti-Imperialist Struggle throughout the World,” offering shorter reports on China, Nigeria, Manchuria, Germany, and Gambia. Most importantly, however, the issue offered a complete presentation of the results of the LAI Executive meeting in Berlin on May 30–June 2. 22 The International Secretariat had expressed high hopes for the review to contribute in reviving the LAI’s position as a global petitioner against colonialism and imperialism. It was now published in English, methodically designed and formatted, and aimed at introducing anti-imperialism as a politically motivated and conscious movement, with the LAI at the forefront of mass struggles. But from the perspective of League’s internal state of affairs and the reactions of a few of the national sections to the directives coming from the LAI’s center in Berlin, the prognosis of the review looked poor from the outset. In London, the secretary of the British LAI section Reginald Bridgeman explained in a letter to the International Secretariat that “the suggestions which you have made with regard to the distribution of the Review indicate that you have got an entirely incorrect idea as to our position.” Bridgeman was above all referring to the “extreme pressure of work” in London due to a shortage of personnel at the office and the added fact that the section had “very little money” to distribute the review in England. 23

Yet this did not deter the International Secretariat from starting preliminary work for the second issue in November. Thögersen informed the Eastern Secretariat that he urgently needed “articles dealing” with India and Manchuria, and that “any book reviews [were] very welcome.” 24 Issues of the review actually continued to be published with Thögersen as chief editor until the end of 1932; but the ensuing power struggle and polarized political scene in Germany curbed any means and resources to publish the LAI’s theoretical organ. While 1932 had been a year in German politics that exposed and vindicated the view that the country had drifted towards “a presidential dictatorship” as a consequence of the tumultuous struggle for power between the far left (communists) and the far right (the Nazi movement), and with Hitler’s ascendancy to power as Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933, the short space of time between November 1932 and the Nazi party assuming formal power proved that it was futile and impossible to push ahead with completing a new issue of the review. Any initiative to do so was regarded as futile by the LAI International Secretariat at their last meeting in Berlin on January 30, 1933, and postponed for the future. 25

The League would go on to produce other literature until its ultimate demise in 1937. But the short-lived run of The Anti-Imperialist Review should not obscure its unprecedented and still highly novel aim: to connect, articulate, and theoretically elaborate ongoing struggles and movements against imperialist power. The Comintern experiment generated some of the first – and most successful – publication efforts towards this end, including George Padmore’s The Negro Worker and its Pan-Africanist continuation outside Soviet influence, the International African Opinion, co-edited with C.L.R. James for the International African Service Bureau. 26 The influence of these transnational hubs of militant analysis and revolutionary activity can be seen in the more recent decolonization sequence of the 1950s–1970s, with journals and periodicals linked to solidarity organizations like the Tricontinental. Certainly, recountings of lost currents of thought and action like the LAI can invoke nostalgia for the political movements, networks, and spaces of the past; but such exercises should more importantly attune us to the strategic coordinates of our present, in which necessarily different forms and visions of anti-imperialist theory and practice still have purchase and significance. 27

References

| ↑1 | See Sukarno’s reference to the LAI in his opening lines: “Only a few decades ago it was frequently necessary to travel to other countries and even other continents before the spokesmen of our peoples could confer. I recall in this connection the Conference of the League Against Imperialism and Colonialism’ which was held in Brussels almost thirty years ago. At that Conference many distinguished Delegates who are present here today met each other and found new strength in their fight for independence.” Achmed Sukarno, “Opening address given by Sukarno (Bandung, 18 April 1955).” See the discussion of the LAI’s influence on Bandung and future anti-imperialist formations in Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York: The New Press, 2003), 16–30. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This text is, primarily, based on my doctoral dissertation and book on the League against Imperialism and for National Independence: “We Are Neither Visionaries Nor Utopian Dreamers”: Willi Münzenberg, the League against Imperialism, and the Comintern (Åbo: Åbo Akademi University. Published as Vol.I–II, Lewiston: Queenston Press, 2013). For a précis, see Fredrik Petersson, “Hub of the Anti-Imperialist Movement: The League against Imperialism and Berlin, 1927–1933,” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 16, no. 1 (2014): 49–71. |

| ↑3 | The Anti-Imperialist Review. A Quarterly Journal Edited and Published by the International Secretariat of the League against Imperialism 1, no. 1 (Berlin: Friedrichstrasse, July 24, 1928). |

| ↑4 | Sean McMeekin, The Red Millionaire. A Political Biography of Willi Münzenberg, Moscow’s Secret Propaganda Tsar in the West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 208, 348. |

| ↑5 | This refers to the Wailing Wall riots between the Jewish and Arab populations in Jerusalem as they had evolved during the summer of 1929. |

| ↑6 | Russian State Archive for Social and Political History, Moscow (RGASPI) 542/1/51, 1-2, Letter from Komfraktion, LAI, Berlin, to Eastern Secretariat, Moscow, 9/1-1931. |

| ↑7 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 26-28, (Vertraulich) Zirkularbrief Nr.8, International Secretariat, Berlin, to the Eastern Secretariat, Moscow, 12/2-1931. |

| ↑8 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 49, Letter from Smeral, Berlin, to Magyar, [unknown location], 7/3-1931. |

| ↑9 | Here is the complete table of contents for the 1928 issue of The Anti-Imperialist Review (Vol. 1, No. 1): Foreword by James Maxton, MP (Great Britain); “In the Name of the Chinese People,” Madame Sun Yat Sen (China); “Greetings,” from S. Srinivasa Iyengar (India); “From Demonstration to Organisation,” Willi Münzenberg MP (Germany); “The Colonial Policy of the Labour and Socialist International,” Clemens Dutt; “The Chinese Revolution and the Northern Campaign of the Kuo Min Tang,” Asiaticus; “British Imperialism in India. A World Menace,” Shapurji Saklatvala. MP (Great Britain); “The Latest Development of Dutch Imperialist Policy in Indonesia,” Mohammad Hatta; “Anglo-American Imperialist Rivalry in Africa,” Max Leitner; Documents on the Colonial Question; Book Reviews; Report on the Development of the League Against Imperialism. |

| ↑10 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 50, Letter from Magyar, Moscow, to “Komfraktion,” Berlin, 11/3-1931. |

| ↑11 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 51, Zirkularbrief Nr.10, Fraktion der LAI, Berlin, to Eastern Secretariat, Moscow, 14/3-1931. |

| ↑12 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 52, Zirkularbrief Nr.11, Fraktion der LAI, Berlin, to Eastern Secretariat, Moscow, 15/3-1931. |

| ↑13 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 56, Brief Nr.12, LAI, Berlin, to Magyar, Moscow, 25/3-1931. |

| ↑14 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 77, Unterstützt eine neue anti-imperialistische Zeitschrift, Hans Peter Thögersen, Berlin [stamped date: 7.4.1931]. |

| ↑15 | Petersson, League, 426–39. |

| ↑16 | RGASPI 542/1/49, 208, Protocol: LAI Executive meeting, Berlin, 31/5-2/6-1931. |

| ↑17 | RGASPI 542/1/49, 281-287, Bericht des Bureaus der Fraktion der Exekutivsitzung der Liga gegen Imperialismus, author: Ferdi, [stamped date, on arrival in Moscow: June 27 1931]. |

| ↑18 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 128, Letter from Ferdi, Berlin, to Magyar, Moscow, 8/7-1931. |

| ↑19 | This refers to all kind of materials the International Secretariat depended on to complete the review. For example: proper intelligence from the colonies (letters, reports); printed material (articles, journals, and books); or assessments written in Moscow at Comintern headquarters on the colonial question. |

| ↑20 | RGASPI 542/1/48, 129–135, Monatsbericht über die tätigkeit der LAI, Berlin, to Eastern Secretariat, Moscow, 15/7-1931. |

| ↑21 | Chatto was executed in Moscow during the Great Terror on September 2, 1937, accused of having been a German spy on Soviet soil. On Chatto, see my above-cited dissertation and book, and Nirode K. Barooah, Chatto: The Life and Times of an Indian Anti-Imperialist in Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). |

| ↑22 | The Anti-Imperialist Review, vol.1, no. 1 (Berlin: League against Imperialism, September–October 1931). |

| ↑23 | RGASPI 542/1/52, 26, Letter from Bridgeman, London, to International Secretariat, Berlin, 26/8-1931. |

| ↑24 | RGASPI 542/1/49, 324, (Table of contents, draft) Anti-Imperialist Review, vol.1, no. 2 (Berlin: League against Imperialism, November 1931). |

| ↑25 | Petersson, League, 452, 487-91. |

| ↑26 | See Anthony Bogues, “The Notion and Rhythm of Freedom: The Anti-Colonial Internationalism of the International African Service Bureau,” in Internationalismen: Transformation weltweiter Ungleichheit im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, ed. Karin Fischer and Susan Zimmermann (Vienna: Promedia, 2008), 129–46. |

| ↑27 | See Fredrik Petersson, “Anti-imperialism and Nostalgia: A Re-assessment of the History and Historiography of the League Against Imperialism,” in International Communism and Transnational Solidarity: Radical Networks, Mass Movements and Global Politics, 1919-1939, ed. Holger Weiss (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 191–255. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine