“You don’t know much about history. You don’t know much about anything, right? You are terribly ignorant, Mr. Danger, an ignoramus. You are a donkey, Mr. Danger…. You are a donkey, Mr. Bush.” – Hugo Chávez

The year 1492 marks a turn. 1 For the indigenous population of the Americas, it signifies the closure of self-determined history and the beginning of near demographUSic annihilation. From the vantage point of Spanish and Portuguese rulers, the same moment signals the ascent of far-reaching feudal empires and the concomitant rewards of extraordinary geographic preponderance. Asymmetrical encounters of Europeans, Amerindians, and Africans over the next centuries trace their origins to this calendric notch. For Latin Americans and the Latino diaspora today, the resonances of 1492 nestle in every crevice. 2

Seizing on the quincentenary of Columbus’s arrival to the Caribbean, in 1992 indigenous movements across the Americas launched the latest renewal of anticolonial tradition; such revivals represent the leading edge of emancipatory endeavor in Latin America in recent times, from the explosive dynamics of indigenous power in Ecuador in the 1990s, the Zapatista insurrection in Chiapas in 1994, to the left-indigenous quasi-insurrectionary cycle in Bolivia between 2000 and 2005.

Age of Revolution

Just eleven years before the beginning of the slave insurrection that would culminate in the Haitian Revolution, 3 a crisis of Spanish colonial rule at the end of the 18th century was pregnant with the promise of redemption elsewhere in the Americas. The Great Andean Civil War of 1780–82 featured uprisings led by indigenous authorities in what is present-day Bolivia and Peru. Insurgencies helmed by Tupac Amaru and Tupac Katari threw into question both European and creole sovereignty in the Americas, proposing in their place projects of indigenous territory and political authority. 4 The forces of Amaru, inspired by the promise of return to Incaic rule, arraigned themselves in a sustained rebellion around Cuzco. Katari, with tens of thousands of indigenous troops behind him, laid siege to La Paz for over six months. Repression was fierce and ultimately put a cruel end to these rebellions. Colonial clampdown from above would for some time after the formal independence of Bolivia and Peru continue to cast its long shadow on socio-political and cultural relations in these countries. 5

Prior to being drawn and quartered for his protagonist role in 1780–81, Katari warned the colonialists that he would “return as millions,” and the indigenous rebels of 21st-century Bolivia continue to see themselves as the embodiment of this return. 6 Similar echoes of resurrection can be heard today, from Mexico to Chile, in the recovery of Abya Yala, the pre-colonial name given to the American continent by the Kuna people of present-day Panama and Colombia, one subaltern alternative to “Latin America.”

Politically, the movements for independence from Spain and Portugal in the early nineteenth century exhibited none of the cataclysmic challenges to the reigning social orders embodied earlier in the Haitian eruption, or in the thwarted Andean insurgencies. Instead, internecine disputes between European settlers living in the colonies and their political overseers in Spain and Portugal were the central drivers of the independence wars. Formal political independence did not, therefore, usher in a parallel upturning of social hierarchies, and for many of the indigenous, African, and mestizo laboring classes, everyday life persisted in a manner not dissimilar from that of the colonial era. In one expression of this palpable underlying continuity across distinct political forms of domination, radicals in post-independence Ecuador lined the walls of the capital, Quito, with a graffiti of bitter poetics: “the last day of despotism, and the first day of the same.” 7

Race Prisms

The idea of a “Latin race” first surfaced in early 19th-century Europe, as an amalgam of romantic nationalism and scientific racism spurred European identification of nations with races and languages. First connoting the use of Romance languages and adherence to Catholicism within “Latin Europe,” by the 1830s French intellectuals had extended the notional embrace of the Latin race to include the former Iberian colonies in the Americas. In so doing, French imperial ambitions in the New World sought justification through reference to ostensible cultural affinities, as against the alien protestant expansionism of Anglo-Saxon Britain and the United States. Such a heady brew of affirmed propinquities undergirded French intellectual support for their nation’s occupation of Mexico later in the century (1862–1867). 8

The Latin idea did not hold water with Spanish American elites in the early republican period, however. Americanos and América were the preferred nomenclature following the wars of independence against Spain, with Americano assuming an anticolonial gravitas, and a scope that extended beyond descendants of Europeans to include, albeit unequally, people of indigenous, African, and mixed-race heritage. 9 Spanish American elites, like their North American equivalents, celebrated the notion that “America” writ large “represented a renovating world force distinct from archaic Europe.” 10 Beginning in the 1830s, political elites in Central America and South America then tended to alter their usage to Hispano-América, in an effort to distinguish Spanish American peoples south of the Río Grande from an increasingly expansionist U.S. state, one employing the supposed biological superiority of the Anglo-Saxon white race as ideological cover for its headways into Mexican territory. The meaning of “Hispanic American race” was, in the minds of Spanish American elites at the time, still more culturally than biologically inflected, and thus could include non-white Spanish speakers. 11

In the mid-19th century, the meaning of “Latin America” was adapted and transformed by Spanish American liberals, shifting from a French imperial concept to a richly contradictory anti-imperialist framework of elitist liberal democracy. 12 The new framework emerged in opposition to French imperial designs in the region, Spanish efforts to recover territory lost in the independence wars, and, above all, a novel escalation of U.S. imperial dynamics as Washington’s aims for dominance over its southern backyard quickened and clarified in the protracted wake of the Monroe Doctrine, first introduced in the early 1820s. “Latin” served as a more adept adjective than “Hispanic” in this period, as inclusion of the most powerful state in South America, Portuguese-speaking Brazil, into the novel geopolitical conception was seen as essential to any successful opposition to intensifying U.S. incursions.

However, for Spanish American nationalists there were two Americas, one “Latin,” which was wedded to the principles of New World sovereignty and democracy, and the other one linked to the United States, which was steadily more imbued with militarism and expansionary belligerence. “What is often taken for anti-Americanism in Latin America,” the historian Greg Grandin writes,

is, in fact, a competing variation of Americanism. During the first century of independence from Spain, Latin American intellectuals and politicians developed a nationalism that was at once particular – acutely attached to a specific national and regional place – and universal – a belief that the Americas represented an exceptional opportunity to fulfil the promise of the modern world. That modern world was inescapably defined in relation to the rise of U.S. power in all of its expressions, leading nationalists to adopt a defensive posture. 13

In April 1855, William Walker led a band of U.S. filibusters – the term used in the 1850s to describe U.S. citizens who invaded Latin American states with which the United States was formally at peace – from San Francisco to Nicaragua, at the invitation of Nicaragua’s opposition Liberal Party, which was ensconced in civil war with the ruling Conservative regime. The Walker group eventually seized power, forging plans thereafter to wage war on other Central American states. Walker was driven by a vision of a new, independent settler-colonial empire. U.S. president Franklin Pierce officially recognized Walker’s regime as legitimate in 1856, and Walker’s exploits were celebrated in the mainstream U.S. press. 14

Such was the principal catalyst for Central and South American liberal diplomats, intellectuals, and politicians to forge an anti-imperial alliance under the banner of “Latin America” for the first time. The new anti-imperialism was aligned against European and U.S. intervention in equal measure.

The resonance of “Latin America” as a geopolitical entity, and as a basis for anti-imperialism, also gained force in the midst of the brief and tenuous, but nonetheless essential, political opening in the 1840s and 1850s across much of Latin America, driven from below by urban popular classes and restless peasantries. In 1853, the most advanced expression of this tentative democratization was New Granada’s – now Colombia and Panama – constitution, which granted universal suffrage to all males without exceptions rooted in ownership of property, literacy, or color. The other dramatic levelling of the period was, of course, the abolition of slavery in the bulk of Spanish America, drawing a color line between this new state of affairs in the region and the continuity of slavery in the United States. 15

In a certain sense, then, “Latin America” so conceived was a source of oxygen to the blood of republican sovereignty, democracy, and anti-slavery coursing through the veins of Spanish America in the mid-19th century. At the same time, however, liberal republican opinion among the dominant classes had not assuaged its intrinsic panic in the face of the always unruly, and now more assertive, lower orders; indeed, their anxieties were newly aroused by democratic pressures stemming from below. The inclusiveness of the regional label was thus highly contested.

Among some liberal advocates of “Latin America,” such as the Chilean Francisco Bilbao, the “Latin” race was conceived in cultural opposition to the “Anglo-Saxon” race of the protestant United States, but could include the non-white popular layers south of the Río Grande, so long as they spoke Spanish or Portuguese and adhered to the tenets of Catholicism. 16 For others, like Argentine intellectual Juan Bautista Alberdi, though, Latin denoted a blood tie to Europe, with those in the Americas designated as neither Latin nor Saxon – those of indigenous, African, or mixed-raced ancestry – relegated to the ranks of barbarians. Such would be the ideological foundation for the Argentinian state’s genocidal “Conquest of the Desert” only a short time later, in the 1870s. 17

As the scientific racism of “polygenism” – the notion that racial differences were biologically fixed and immutable – gained force in France and the United States with the advance of the 19th century, similar ideas would disseminate through much of Latin America, with elites increasingly identifying “Latin” with whiteness. But in the 1850s, such biological conceits were still nascent, underdeveloped, and unevenly dispersed, and thus the anti-imperial, sovereigntist, and democratic accent of incipient “Latin America” persisted parallel to reactionary invocations of the “Latin” race. 18 At times, these were articulated together: liberal exponents of republican racism could insist upon the superiority of democracy, anti-slavery, and sovereign rule, while simultaneously identifying themselves as “white,” and thus ultimately better fit for republican rule than the lower, mixed-race social classes.

“So although ‘Latin America’ was linked with anti-imperialism and democracy,” writes historian Michel Gobat, “the concept gained widespread popularity only after it had shed its identification with whiteness. This did not occur until the early twentieth century, when the resurgence of U.S. interventionism led proponents of ‘Latin America’ to increasingly associate the concept with the defense of the continent’s mixed races.” 19

U.S. Expansion

The sheer relentlessness of U.S. aggression – “the Texas secession, the Mexican-American War, Walker’s invasion of Nicaragua, the Spanish American War, the annexation of Puerto Rico and the Philippines, the Platt amendment, Roosevelt’s corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, brief occupations of Mexico and Cuba followed by longer stays in Haiti, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic” 20 – acted like an insistent drumbeat in the formation of Latin American geopolitical consciousness.

Anti-imperialism underwent a metamorphosis, however, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as liberal elitism lost its grip on the subject matter, and Marxist theory and praxis entered its incubatory phase. That this passage of the baton from liberalism to Marxism transpired more or less parallel to the transition to capitalism in much of Latin America in the late 19th century is notable – the force of Marx’s ideas only really acquires life in such a context. 21 An initial gestation of Latin American Marxism (1870–1910) involved the dissemination of the writings of Marx and Engels in the region, alongside the organization of the first Latin American sections of the Communist International, and initial elaboration of socialist programs in places like Cuba, Mexico, Uruguay, and Argentina. 22

The second, revolutionary phase (1910–1930) kicked off with the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and brought to the surface the problems of land, indigenous liberation, the unity of Latin American peoples from the new vantage point of the popular classes and oppressed groups, the role of national and anti-imperialist struggle, and the socialist character of envisaged revolutions on the horizon. In the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917, the first Communist Parties were formed – Argentina (1918), Uruguay (1920), Chile (1922), Mexico (1919), and Brazil (1922). This was the era of giants, like Cuban revolutionary Julio Antonio Mella, and, most decisively, Peru’s José Carlos Mariátegui, to this day Latin America’s most original theoretician. 23 Of course, all the phases of Latin American Marxism mentioned here are schematic, heuristic attempts to capture fluid and contradictory historical processes, and therefore should not be interpreted as hard-and-fast historical breaks.

“In the twentieth century,” Grandin reminds us, “anti-imperialist activists such as Nicaragua’s Augusto Sandino and Peru’s Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre democratized and racialized the antinomy” of the long-established two Americas, “arguing that Latin America constituted a unique ‘Indo-American race’ distinct from Anglo-Saxon America: they offered a popular patriotism that Latin America’s majority poor could sympathize with, one that superseded elite nationalism by valorizing dark-skinned, impoverished peasant culture that prevailed throughout Mesoamerica and much of South America.” 24 There is a sharp distinction here from earlier, racist iterations of “Latin America.”

Populist Anti-Imperialism

Yet there were strict limits to certain variants of populist anti-imperialism. Haya de la Torre’s Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA) in Peru, for example, drew on a nationalist mythology of mestizaje, or mixed race national identity, that was rooted in a particular form of indigenous romanticism. 25 This perspective froze a folkloric, ancient indigenous identity in the heart of the national imaginary, while erasing the living reality of indigeneity and exalting mestizo hegemony in the present. 26 That this went hand in hand with an anti-imperialist strategy of multiclass populism, and fantasies of a progressive national bourgeoisie, was no coincidence.

In the work of Mariátegui, by contrast, a utopian-revolutionary dialectic borrows selectively from the indigenous precapitalist past to fortify a forward-looking vision of socialist emancipation. Strategically, the revolutionary subjects are workers and peasants, oriented in opposition not just against foreign capital but vis-à-vis class enemies at home. Mariátegui’s vision struck simultaneously at the core of Comintern orthodoxy – he was denounced as a populist for his particular appeals to the indigenous peasantry, as well as his stubborn resistance to anti-imperialist alliances led by the bourgeoisie or petty bourgeoisie – and the reigning nationalism of his country, as captured in Aprista ideology.

“His is a double combat,” write Omar Acha and Débora D’Antonio. “In the first place, with Aprista populism that postulated the necessity of capitalist and anti-feudal development. In the second place, with the ‘stagism’ of the Comintern….” 27 According to Acha and D’Antonio,

Mariátegui conceives of the revolutionary capacity of the indigenous masses and the liberation from the yoke of the landowner in the manner of Sorel; that is, in connection with the formation of myths and hopes of redemption that propel the oppressed classes toward socialist revolution. The myths are not arbitrary representations, or imaginary constructions, because they respond to historical experiences and material situations. In the case of the urban proletariat, Mariátegui conceives their revolutionary potentiality in classical Marxist terms; that is to say, considering their position in the productive system and their objective confrontation with the capitalist class. With respect to the peasantry, the revolutionary mythology is rooted in real communities, and its traditions are embodied in the ayllus, where Mariátegui discerns social relations similar to socialist relations. That inheritance makes possible a transition to socialism on such bases, but in a sense of surpassing [them]. 28

For Mariátegui, the indigenous community is “still a living organism.” It survives, “despite the hostile environment that suffocates and deforms it.” Beyond mere persistence, the indigenous community “spontaneously manifests obvious possibilities for evolution and development.” 29 Invoking their communal vitality, their stalwart cooperative bonds of cooperation and solidarity in the face external pressures of market and state, Mariátegui explains how, “in indigenous villages where families are grouped and bonds of heritage and communal work have been extinguished, strong and tenacious habits of cooperation and solidarity that are the empirical expression of a communist spirit still exist. The community draws on this spirit. It is their body. When expropriation and redivision seem about to liquidate the community, Indigenous socialism always finds a way to reject, resist, or evade it.” 30 Again, in the dialectical utopian-socialist framework of Mariátegui, the perceptive embrace of the indigenous community as living organism does not require some kind of impossible, nostalgic return to the Inca past; for Mariátegui, this was an outlandish idea. Indigenous socialism’s vitality persists alongside a call for the popularization of Einstein’s physics, and an accelerated incorporation of all of modern civilization’s achievements into Peruvian national life. 31

Mariátegui’s meticulous study of the history of colonialism, Peru’s integration into the world market, and the ongoing imperialist character of the global capitalist system in the early 20th century, led him to develop a thoroughgoing and original anti-imperialist perspective. With the unity and simultaneity of anti-imperialism and revolutionary socialist politics at its core, this optic finds its clearest expression in the document, “Anti-Imperialist Point of View,” submitted to the First Latin American Communist Conference in Buenos Aires in June 1929. Here Mariátegui savages the complicit role played by Latin American national bourgeoisies in the perpetuation of imperialism, which they saw as “the best source” of their own profits and the continuity of their own political power. 32 Any coherent anti-imperialist alliance could not therefore be led by bourgeois or petty bourgeois forces under the banner of nationalism – under such leaders there would be no rupture with imperialism. Instead, the only possible winning alliance would have to be forged and led by workers and peasants, in a combined movement of anti-imperialism and commitment to revolutionary socialism at home. “We are anti-imperialists,” Mariátegui stressed, “because we are revolutionaries, because we oppose capitalism with socialism as an adversarial system called to succeed it. In the struggle against foreign imperialism we are fulfilling our duties of solidarity with the revolutionary masses of Europe.” 33

Stalinist Interregnum

The revolutionary phase of Latin American Marxism, set in motion by the Mexican and Russian revolutions, was brought to its tragic conclusion in 1932 in El Salvador. In January of that year, thousands of indigenous and ladino (non-indigenous) rural laborers made waves in protest against electoral fraud and the repression of strikes. Rebels seized control of a number of municipalities in central and western El Salvador. The uprising was organized by Communists, many of whom were themselves indigenous rural laborers and union militants of the coffee plantations. The Salvadoran military and allied paramilitary militias quickly won back the towns and massacred thousands of mainly indigenous rural activists. 34 The leaders of the Communist Party in El Salvador – Farabundo Martí, Alfonso Luna, Mario Zapata, and Miguel Mármol – had been imprisoned prior to the insurrection, in a preventive crackdown orchestrated by the state. Party documents of the period demonstrate that the aim of the upheaval was nothing short of socialist transformation of Salvadoran society, and that the initiative was born independently from any directives emanating from the Kremlin. 35

In the decades following the Salvadoran massacre, the main currents of Latin American Marxism lost such independence and audacity. Communist Parties throughout the region were systematically brought under the thumb of Stalinism, in what was to be a painfully sclerotic phase of Marxism, lasting until the 1959 Cuban Revolution. For the bulk of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, the dogma of Stalinist development-by-stages prevailed, with any revolutions in Latin America to be contained within the boundaries of the national-democratic type, in accordance with the region’s presumed feudal phase of development. On this view, a long period of industrial capitalist development was the next step in progress, necessitating political alliances in the short and medium term between the popular classes and “progressive” national bourgeoisies. Socialist revolution would only be possible sometime in the distant future, once productive forces had been sufficiently advanced. 36

Cold War Configurations

Global transformations accumulated in rapid succession. The world wars, together with post-war national liberation movements in Asia and Africa, undermined European and Japanese imperial power, and the United States replaced Britain as global hegemon. The United States sought to restructure the world system in such a way as to ensure the reproduction of a liberal capitalist order on a world-scale, and its own position at the top of the hierarchical order of states within that system. Experiments in independent nationalist development over the next few decades, as part of various national-populist projects in the Global South, threatened the system not with revolutionary rupture, but with the more temperate example of basic self-determination they might set for others.

In the Latin American context, the perpetual bogeyman of Soviet expansionism – more imagined than real in most cases – was a convenient and flexible pretext for undermining even modest initiatives of tentative insubordination by weak Latin American states in the face of the reigning world order. The U.S. state sought to protect the interests of capital – its own capital first, but often global capital by association – on the international plane through the maintenance of a global economic order amenable to market penetration. Social forces and governmental forms that got in the way of global accumulation – even indirectly – were to be undermined through one pathway or another.

The CIA-backed coup in Guatemala in 1954, which ousted the democratically elected administration of Jacobo Arbenz, ushered in the era of the Soviet pretext. Eisenhower condemned the Arbenz government as a “Communist dictatorship” despite the Guatemalan government’s overt commitment to a nationalist modernization project of capitalist development, involving agrarian reform, recognition of trade unions, literacy campaigns, some nationalization – crucially the lands of the United Fruit company – and protections for domestic industries. Of the 51 seats in the National Assembly held by the Arbenz coalition, only four were in the hands of the Guatemalan Labor Party, the name assumed by domestic Communist forces in the country at the time. The coup ended democracy in Guatemala for the next four decades, and fueled rounds of counter-insurgency that left hundreds of thousands dead. 37

Washington attempted variations of the same in response to the Cuban Revolution (1959–), the “peaceful road to socialism” in Chile (1970–1973), and the Sandinista Revolution (1979–1990) in Nicaragua. In place of overt military intervention, the central means of U.S. interference were mammoth infusions of counter-insurgent aid to allied anti-Communist forces, whether in the form of allied dictatorships that had captured state power, or right-wing terrorist death squads and paramilitary formations where the Left was in power. Washington facilitated an extraordinarily sustained level of violence throughout Latin America’s Cold War. In Central America, the U.S. Central Command coordinated and financed a Central American Military System for Telecommunications and other forms of synchronization across state intelligence agencies, while in the Southern Cone of South America, the U.S. established the transnational state-terror network Operation Condor, providing logistical, technical, financial, and military support to the dictatorships of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil. 38

Dependency Theory

A third phase of revolutionary experimentation in the history of Latin American Marxism (1959–1980) begins with the Cuban Revolution, passes through Allende’s Chile, takes a last breath in Sandinista Nicaragua, and is quickly eclipsed by the neoliberal counter-reformation of the 1980s and 1990s. The many internal threads and currents of dependency theory were a central part of this intellectual and political tumult.

In her important recent study of Latin American social theory of the 20th and early 21st centuries, Maristella Svampa treats the span from 1965 to 1979 – the apogee of dependency theory – as one of Latin America’s most intellectually fertile periods. 39 The political context was one of expanding authoritarian rule, with successive coups from the mid-1960s to mid-1970s in Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay, Chile, and Argentina. Brazil, Chile, and Mexico take pride of place in this telling of dependency’s history, the first as the country of origin of many of the classical theorists – Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Theotonio Dos Santos, Ruy Mauro Marini, and Vânia Bambirra – and the latter two as uniquely fecund habitats of exile.

Santiago was a favoured destination for radical Brazilians following the coup d’état in their home country in 1964, and Mexico for Chileans escaping Pinochet in 1973, as well as those Brazilians residing in Chile at the time and thus forced to flee a second time. André Gunder Frank, a German economist with a Chilean wife, destined to become an iconic – if commonly ridiculed – figure of dependency, passed considerable time teaching in Brazilian and Chilean universities. Paramount interlocutors under the broad dependency umbrella outside of these three countries included Edelberto Torres Rivas of Guatemala, Aníbal Quijano of Peru, and Pablo González Casanova and Rodolfo Stavenhagen of Mexico, to name just a few.

The engrossing story of dependency’s origins includes seminars on Marx organized at the Universidad de Sâo Paulo by Cardoso and Arthur Giannoti, beginning in 1958. These had a decisive impact on a generation of students and contributed to the revival of Marxism in the universities of Brazil. Svampa relates how Dos Santos recalls both the original Brazilian seminars on Marx, and reading groups on dialectics and Capital, as well as how they were reimagined and reconstituted in exile in Chile after 1964, at the Centro de Estudios Socio-Económicos (Centre of Socio-Economic Studies, CESO) of the Universidad de Chile in Santiago. While young Brazilian Marxists were aware of similar study groups in Paris, under the wing of Louis Althusser – producing, among other notable works, the collectively authored, Reading Capital, in roughly the same moment as the early texts of dependency 40 – the Brazilians preferred the young Marx, Jean-Paul Sartre, and György Lúkacs, over Althusser, Étienne Balibar, and Jacques Rancière, at least according to Dos Santos’s retrospection.

On the one hand, dependency marked an epistemological break with the economic structuralism of mainstream institutions such as CEPAL 41 ; at the same time, it represented a visceral riposte to the stodgy theoretical dogmas, political pragmatism, and stagist determinism of Stalinized Communist Parties throughout the region in that era. Eclectic points of political reference for dependentistas were instead the Cuban Revolution, widening guerrilla movements, and Chile’s road to socialism under Allende.

Svampa’s survey is equally attentive to recurring commonalities running through dependency, and internal incongruence and idiosyncrasy. Three points of commonality emerge. First, the obstacles to development in peripheral societies spring from the mode of their articulation with the international system, the effects of which have to be understood as much in their structuring of internal, national dynamics to these societies – becoming interior to them – as in the external structures of the system as a whole. Second, most theorists of dependency thought of it as a more concrete mediation of the general theory of imperialism, premised more than anything else on the unity of capitalism as a world system. Third, most dependency theory saw the 1960s and 1970s as a new period of capitalism, linked to the growing presence of monopoly capital in dependent societies. Dependency theory was a master framework of the era that encouraged the articulation of a space for Latin American debate, and the circulation of original ideas “which opened up the possibility of speaking of Latin America as a historical-political unity, beyond the evident internal differences.” 42

Probably the most influential single text of dependency was Dependencia y desarrollo en América Latina, by Cardoso and Enzo Faletto. 43 It was first published in 1969, but preliminary drafts circulated widely in the preceding two years. Frank’s oeuvre was also important, particularly in disseminating some of the concepts of dependency throughout the Anglophone world, but also within Latin America, especially through his book El desarrollo del subdesarrollo. 44 That said, Frank’s version of dependency was perhaps the crudest and most mechanical on offer. Socialismo o fascismo and Imperialismo y dependencia are two of Dos Santos’s critical contributions. 45 Bambirra, one of the only women theorists of dependency to achieve renown at the regional level, is still routinely written out of its history, but texts such as El capitalismo dependiente latinoamericano situate her indisputably as an essential figure of the revolutionary wing of dependency, alongside Marini. 46

In many ways, Marini’s seditious life maps onto the history of dependency’s contested theoretical production. A member of Politica Operaia in Brazil when the 1964 coup took place, he fled to Chile, where he became a leading figure in the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (Revolutionary Left Movement, MIR). While in Chile, he also pursued intellectual work within the institutional parameters of CESO. The Chilean coup of 1973 forced him into exile once again. He split his time between Germany and Mexico, before eventually settling in the latter with a place in the Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Marini’s Subdesarrollo y revolución was published in 1969, but Dialéctica de la dependencia, published in 1973, was to become his most lasting contribution. 47 Marini’s innovative conceptualizations of “super-exploitation” and “sub-imperialism” continue to inform current Latin American debates in the critical social sciences.

A Long Neoliberal Night

If the rough periodization of Latin Marxism offered so far suggests an initial set of four stages, a fifth (1980–2000) maps onto the regional reign of neoliberal orthodoxy, and is unsurprisingly characterized by retraction, defeat, and self-criticism, although also by renovation at the margins. This was the era of abandoned revolutionary strategy, the fall of the Soviet Union and its client states, the transition to capitalism in China, the isolation of the Cuban Revolution, and the defeat of the Nicaraguan Revolution. Most Latin American Marxist intellectuals decamped, opting for post-Marxism or straightforward liberalism. 48

Neoliberal restructuring radically transformed class structures in the region, decomposing old-Left social bases in trade unions and peasant associations. Left-wing parties went the way of most Marxist intellectuals – adapting to the parameters of debate proscribed by the new liberal epoch. The right-wing dictatorships of the 1960s and 1970s had been transformed into electoral regimes, but the legacy of their dirty work lingered like a nightmare.

Dictatorships of the Southern Cone, and the counter-insurgencies of Central America, had murdered hundreds of thousands. Along with lasting effects of collective psychological terror, the socio-political roots of the Left in these societies had been annihilated. Few of the usual conveyor belts of collective memory in the history of the twentieth century Left – experienced cadre, formal associations, and informal cultural infrastructures – remained to pass on lessons to a new generation; and besides, Latin American social structures had been so deeply transformed by state terror, imperial intervention, and capitalist counter-reform that any new Left to emerge at this stage would necessarily look much different than what had come before, even if it would have to draw – as all new Lefts must – on critical investigation of the past. 49 Latin American radicals in the 1980s and 1990s survived mainly through the art of waiting impatiently in non-revolutionary times. 50

Crisis and Renewal

The light of a new dawn arrived in the late 1990s. Between 1998 and 2002, South America experienced the worst recession since the height of the debt crisis in the 1980s. The economic crisis of neoliberalism – with earlier utterances in Mexico in 1994, Southeast Asia in 1997, and Russia in 1998 – had made its bold entrance into South American markets. Poverty, inequality, unemployment, and peasant dispossession – all of which had steadily worsened through the two preceding decades in which Latin America was transformed into a Hayekian laboratory – experienced a sharp spike. The answer of ruling conservative and liberal governments was to up the dosage of the same medicine. While this had had some appeal to popular classes in Latin America suffering under the weight of hyperinflation and stagnation in the early 1980s, after twenty years of firsthand participation in the failed drug trial of neoclassical economics, the promise of more of the same rang hollow.

A new extra-parliamentary Left erupted in different colors across the sub-continent. In Argentina, unemployed workers led the way; in Bolivia, novel left-indigenous, rural and urban coalitions of social struggle, and in Ecuador the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities (CONAIE), were followed by the militant public sectors of the labor movement. Neoliberal governments were toppled as the economic crisis of neoliberalism matured into an organic crisis of rule. By the mid-2000s, as recession turned to dynamism with the onset of a Chinese-driven world commodities boom, the extra-parliamentary Left found muted expression on the electoral terrain as Centre-Left and Left governments took power nearly everywhere in South America.

The limits of the Left in office – even in the more radical experiments of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela – proved sharp, once the easy rent of commodities subsided, beginning in 2011, and the costs of conciliation with capital came more visibly to the surface. The class decision by most of these governments to transfer the costs imposed by newly austere state coffers onto the popular classes, rather than onto capital, meant that they began to lose legitimacy among their erstwhile loyal social base. Meanwhile, capital that had only reluctantly learned to live with these governments – once it had become clear that their net profits would not be endangered – abandoned ship to return to their natural home of reviving configurations of the old and new Right. Left governments fell through military or parliamentary coups in Honduras, Paraguay, and Brazil, and through presidential (Argentina) and congressional (Venezuela) elections elsewhere. The tide is turning, but it is a new impasse that the region has reached, rather than an easy renewal of right-wing hegemony. Even as the Centre-Left is in a state of prolonged political crisis, the Right has no solution to the economic travails it has inherited.

A New Left, A New Marxism?

The richness of the extra-parliamentary cycle of revolt, and the contradictions of subsequent left-government rule, unsurprisingly spurred a new period of Latin American Marxism (2000–). It is perhaps imprudent to make summative judgements on key features of the theory and praxis generated thus far, and assuredly over hasty to determine whether the phase of Marxism begun in 2000 is drawing to a close in tandem with the end of the political cycle of the latest Left turn. But one tentative conclusion might be hazarded – the latest season of Latin American Marxism has been characterized by the kind of bursts of originality and profundity last witnessed after the Cuban Revolution, and, at the same time, signs of sclerotic rigidity and formulaic dogma that preceded it. Winds of transformation and restoration wrestled each other indeterminately through this latest storm of the region’s Left.

Some of the intellectual highs and lows are visible in the outpouring of recent works on imperialism and anti-imperialism. We can document such polarities, at least in a preliminary fashion, through a comparative juxtaposition of recent work by two of the region’s weightiest theoreticians: Atilio Borón and Claudio Katz, both highly acclaimed Argentine Marxists. What is most striking in examining their distinct treatments of contemporary imperialism and anti-imperialism are their different theorizations of the relationship between capitalism and imperialism. Borón, on the one hand, implicitly absorbs a number of Realist axioms from orthodox academic debates in North American International Relations, the most important being the near-total separation of the sphere of “geopolitics” from the laws of motion of capital accumulation as they unfold unevenly in and through the world market. This is not merely a heuristic separation for analytical purposes in Borón’s analysis, but purports to document a real separation. Thus a window is opened to hyper-contingent and, at times, conspiracist readings of U.S. domination and its ostensible decline over the last few decades. For Katz, by contrast, the economic and the political are often out of sync in their specific temporalities, but there is nonetheless always a dialectical relation between the two. A better balance between objective determination and historical contingency is thus possible in this framework. Capitalist dynamics running through the world market over different phases of capitalist development internationally are understood to set limits on political maneuver for the asymmetrically positioned, constitutive parts of the totality. The same capitalist dynamics contain internal contradiction, and tend toward recurrent systemic crises, potentially opening up political opportunities.

América Latina en la geopolítica del imperialismo, by Borón, is perhaps the most eminent contribution to the latest wave of work in this area. 51 The book received a conspicuous boost in stature when it won the 2012 Premio Libertador al Pensamiento Crítico prize, established in 2005 by Hugo Chávez, and administered by the Red de Intelectuales, Artistas y Movimientos Sociales en Defensa de la Humanidad (Network of Intellectuals, Artists, and Social Movements in Defence of Humanity).

Audacious in ambition, Borón’s panoramic vision in this text moves in and out of broad theoretical controversies – classical and contemporary – and the concrete historical and political terrains of Latin America. He surveys classical questions of Marxist imperialist theory since the late 19th century and offers a novel synthetic framework for understanding the present machinations of global geopolitics. On that backdrop, Borón makes a first foray into more concrete analytical claims surrounding the general crisis of capitalism that erupted in 2007–08 and the questions it posed and poses for the apogee or decline of American empire. Regarding Latin America, he tracks the strategic centrality of the region in U.S. foreign affairs, from the Monroe Doctrine of the early 19th century to the Free Trade Area of the Americas initiative in the early 21st. This explains, for Borón, why the intensified militarization of American power around the globe includes an impressive tentacular reach – through military bases, covert operations, joint military exercises, and the “war on drugs” – into Mexico, across Central America, and throughout parts of South America.

A series of interwoven thematics are at the center of Borón’s account: the question of natural resources, both as a strategic motivation for U.S. intervention and domination, but also as a source of debate and contestation between social movements and left-wing governments over the character of “extractivism” during the accelerated commodities boom of 2003–2011; the specificities of U.S. military extension into Latin America; the difficulties of periodizing recent cycles of popular movements in the region and their relationship to anti-imperialist resistance; and tentative interpretive outlines of a “new epoch” of geopolitical politics on a world-scale.

Much of the book is anecdotal and patchily organized. Intellectuals of lesser renown could ill afford its breezily assertive style. Fundamental theoretical elements – relative U.S. decline, rise of the BRICS, progressive orientation and transformative potential of extant leftist regimes – are more opening gestures than elaborated theses, with internal inconsistencies and soft-spots for conspiracy. But the political conclusions resonate with the most “statist” inflections of Latin American Marxism in recent years – i.e. those closely aligned with governments in office. Leftist opponents of the intensification of extractive capitalism under progressive governments – Raúl Zibechi, Eduardo Gudynas, and Alberto Acosta especially – are caricatured and ridiculed, while indigenous critics of capitalist mining expansion are portrayed as naïve romantics – pachamamistas – in a section relying heavily on a sycophantic reading of recent writings of Bolivian Vice President, Álvaro García Linera. 52

In his strongest thread of argumentation, Borón offers a cartography of military expansion – the agreement between Barack Obama and Álvaro Uribe to establish seven new military bases in Colombia, the vigilant patrolling of the Caribbean basin by U.S. forces, the broad encircling of Venezuela with U.S. military outposts – in the north, in Colombia, and the Dutch Antilles; in the south, bases in Paraguay; in the west, bases in Peru; in the east, those in Guyana, Surinam, and French Guyana. 53 He demonstrates how Plan Colombia, Plan Puebla-Panama, and Plan Mérida, among others, have enabled joint military exercises with local armed forces. 54 Borón also points out the expansion and decentralization of U.S. military bases in recent decades with the U.S. Southern Command’s “forward operating locations,” which are little more than specialized landing strips and crude accompanying infrastructures. With local communications facilities around these strips quickly enabled by the monumental network of U.S. satellites around the world, and the use of enormous C-17 Globemaster transport planes, what appear to be more or less empty sites could be retrofitted, Borón contends, with operational U.S. troops and tanks within hours in most parts of Latin America and the Caribbean. 55 Such insights into the military dimensions of imperialism, however, are underspecified in relation to the dynamics of global capitalism. In an unacknowledged echo of mainstream “realist” theories of North American International Relations theory, geopolitics for Borón appear frequently as a wholly distinct sphere. Each time economics seems poised to enter the analysis, the narrative short circuits back to diplomatic intrigue.

In a degrading turn, which dishonours his landmark early books, Borón lends credence in América Latina en la geopolítica del imperialismo to 9/11 truther theses in several discrete moments of his argument. 56 What accounts for sustained celebration of this book, nonetheless, is perhaps the easy ideological veil it offers the governments of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. All three processes are said to be advancing toward “a socialism of a new type,” a description which for Borón is flexible enough to cover Vietnam and China, despite decades of capitalist restoration 57 The state, so this thesis goes, remains in control and dominance over private capital in these countries, and thus they cannot be described accurately as capitalist. Such a perspective also allows Borón to accept as necessary the totality of market reforms introduced recently in Cuba. 58

The strategic political conclusions Borón draws from history are of a kind with his economic conceptualization of market socialism. From the Allende period in Chile, for example, we are to conclude that the activities of the “most intransigent and radicalized” sections of the Chilean Left, unwittingly and in spite of themselves, “converged” with the interests of imperialism and the domestic Right in the early 1970s, precipitating the 1973 Pinochet coup. This must not be allowed to happen again, he stresses, particularly in contemporary Bolivia, Ecuador, or Venezuela. 59 Allende’s moderation was apparently a plausible exit for that conflictual period, had it not been for radicals to his Left. By contrast, the great historian of the Allende years, Peter Winn, contends that,

in Chile, it was the counterrevolutionaries – not the revolutionaries – who utilized political violence and state terror as a conscious strategy. In the face of this violent counterrevolution, the determination of Allende, the bulk of the Popular Unity to keep to the nonviolent road to socialism may have doomed that strategy to ultimate failure – and condemned Chile to suffer the darkest night of political violence in its history. 60

In the first version, Allende went too fast, reached out insufficiently to his Right, and did so because of the intransigence of the Chilean radical Left. In the second, Allende’s excessive moderation, faith in leadership from above, trust in the established institutions of the capitalist state and the bourgeois opposition’s commitment to democratic continuity, and especially his suspicion of unleashed capacities of those from below and to his Left, are what led to the preventable Pinochet disaster.

Doubling down on key analytical features of his book – the statist conception of socialism, the demonization and caricature of left-oppositional forces in Latin American countries with progressive governments, and the tendency to radically reduce each Latin American conjuncture to the geopolitical expression of imperial power – Borón has more recently compared the 2017 elections in Ecuador to the Battle of Stalingrad, eschewed the possibility of independent left forces in Venezuela critical of Maduro, and interpreted Trump’s arrival to the White House as the “end of the cycle” of neoliberalism, and thus an opportunity for progressive forces in Latin America. 61

In Borón’s theorization and historicization of imperialism, burdened by a geopoliticist idealism, diplomatic positioning by state managers in the core of the world system is granted excessive explanatory power, as is, in terms of resistance, action by progressive state managers of certain Latin American states with centre-left or left administrations. These state managers become the privileged potential agents of emancipation. Class struggle from below is largely eclipsed, despite occasional gestures to the contrary. This eclipse is as true of Borón’s treatment of the United States as it is of Latin America, and it is in part what allows him, finally, to wade into conspiracist waters.

Beneath the Empire of Capital

The two latest books by Claudio Katz are of incomparable sophistication, whatever their internal tensions and misfires. Bajo el imperio del capital, published in 2011, contributes to the latest period of international theorization of contemporary imperialism (drawing on debates in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English), while Neoliberalismo, neodesarrollismo, socialismo, published at the end of 2016, links the wider imperial context to narrower political and economic debates surrounding the last 15 years of leftist experimentation in Latin America. 62

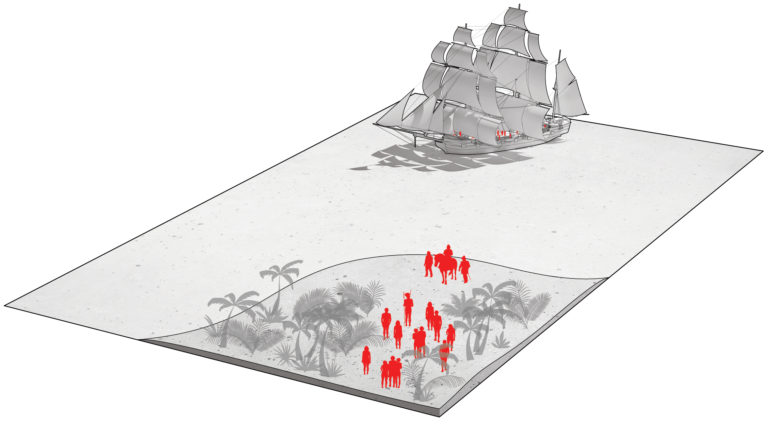

Perhaps the most consequential element in Bajo el imperio del capital is Katz’s careful periodization and characterization of the distinct phases of imperialism since the late nineteenth century – classical (1880–1914); post-war (1945–1975); and neoliberal (1980s–present). 63 Drawing on the theorizations of Lenin, Kautsky, Luxemburg, and Hilferding 64 – at times overlapping, and at others competing – Katz characterizes the classical era as one of ferocious capitalist expansion, with private enterprises playing a protagonist role, in which peripheral territories still external to capitalist laws of accumulation were brought into the system’s orbit through colonial conquest. 65

Here Katz scrutinizes the specificity of distinct modes of production and distinguishes his account from those historians who pay exclusive attention to the rise and decline of empires across centuries – from Rome to Great Britain – without cognizance of the dramatic dissimilarities of the domestic social relations underlying each expansionary state. Following Ellen Meiksins Wood’s Empire of Capital, Katz stresses the analogous relationship between specific forms of domestic social relations and various forms of imperial rule. 66 History suggests that there has been a close association between both capitalist and non-capitalist societies, on the one hand, and their imperialisms, on the other. Non-capitalist colonial empires of the past – such as the feudal Portuguese and Spanish Empires in Latin America between the late 15th and early 19th centuries – like feudal lords in their relations with peasants, dominated territory and subjects through military conquest, often direct political rule, and therefore extensive extra-economic coercion; in contrast, capitalist imperialism “can exercise its rule by economic means, by manipulating the forces of the market, including the weapon of debt.” 67 It is obvious, all the same, that capitalist imperialism continues to require coercive force. As Colin Mooers suggests, “force remains indispensable both to the achievement of market ‘openness’ where it does not yet exist and to securing ongoing compliance with the rights of capital.” 68

Neoliberal capitalism, Katz stresses, witnessed the transformation of the old international division of labor through the internationalization of production and the modularization of global value chains. The systematic transfer of manufacturing activities toward Asia intensified competition and reduced production costs. 69 Massive multinational corporations emerged as key agents in this process. However, contra theses of monopoly capital, 70 the augmentation in size of companies is not synonymous with monopoly control or suppression of competition. Instead, capitalism systematically recreates competition and oligopoly in complementary forms through reciprocal recycling. At certain moments of intense inter-firm rivalry, specific companies introduce transitory forms of supremacy, but these cannot be maintained in the face of new competitive battles just around the corner. This dynamic, Katz insists, is constitutive of capitalism and will persist so long as this particular mode of production survives. 71

Technologically, an information revolution has facilitated the various neoliberal mutations of capitalism, with the generalization of the use of computers in manufacturing and the financial and commercial management of mega-corporations. Radical innovation has increased productivity, cheapened transportation, and enlarged communications networks. 72 However, the internationalization of capital has also enabled more rapid and total transmission of disequilibria in the global system – witness Japan in 1993; Mexico in 1994; Southeast Asia in 1997; Russia in 1998; the so-called dot-com bubble in 2000 in the United States; and Argentina in 2001. This list of regional precursors to the 2008 Great Recession is hardly exhaustive. 73

As in all earlier phases of capitalism, neoliberalism is based on competition and fierce economic rivalry between firms for control of markets. Yet, in the classical phase of imperialism a certain proportionality existed between economic and military rivalry, whereas in the post-war and neoliberal epochs this proximate relationship has been partially displaced and fractured through the military supremacy of the United States. 74 The present system of imperialism is sustained in part through American military intervention and a historically unprecedented global military presence and attendant capabilities. 75

At the same time, U.S. hegemony in the 21st century is much reduced relative to its near-absolute dominance in the first-half of the 20th century. The effectiveness of its military superiority is increasingly in doubt, as the fallout from wars in Afghanistan and Iraq partially demonstrate. 76 Part of the explanation for U.S. military belligerence in the neoliberal period, generally, and the temporally and geographically indefinite character of the “war on terror,” specifically, can be understood as a compensation for declining industrial competitiveness and productivity. In the present moment U.S. military power is employed in part to redress economic deterioration. 77 The United States must constantly reaffirm its global leadership through new wars, Katz insists, but the results of each war are impossible to anticipate, and the instrumentalization of each bloody conflict has become more difficult with the absence of compulsory conscription. 78

The great advantage of Katz’s framework relative to Borón’s is the attentiveness it affords to the underlying character of shifting epochs of capitalist development globally, alongside careful defence against crude economic determinism. Capitalist dynamics in the world system in different historical periods are never reduced to empty abstractions, as though they mechanically determined political outcomes. Katz, following Marx, rises from the abstract to the concrete as he introduces new, specific determinations and mediations across capitalist phases, as these determinations and mediations arise in different regions of the world, in different ways. Class struggle – from above, and from below, and within both dominant and dominated countries – features at the heart of Katz’s historical narrative and theoretical premises. Thus history is open, if not wide-open.

Neoliberalism, Neo-Developmentalism, Socialism

Three analytical findings feature heavily in Katz’s most recent book on the present Latin American conjuncture, Neoliberalismo, neodessarrollismo, socialismo. First, the schema of productive specialization in exports introduced in the 1980s persists to the present, with its accompanying effects – increasing agro-industry, open-pit mining, reliance on remittances and tourism, and a relative decline in industry. The mode of insertion into the international division of labor has not been altered. Second, alongside these underlying tendencies of neoliberal restructuring and its aftermath, national bourgeoisies have been transformed into local bourgeoisies, with ramped up internationalization and association with foreign capital. The biggest local capitalist groups – multilatinas – operate on a regional scale. Third, and finally, the same changes to the economic structure have produced a peasant exodus to the cities, precarity and informalization in the urban labor markets, and discernable frailty in the position of the middle classes. 79

In Neoliberalismo, neodessarrollismo, socialismo Katz devotes his attention to a more detailed account of Latin America within the contemporary world order. It begins with a bird’s-eye survey of the Latin American situation, focusing on the region’s insertion into the international division of labor, and changes in the class structure over the last several decades and their significance for reconfiguring dominant and dominated classes alike. It then shifts to theoretical and empirical discussions of neoliberalism, neo-developmentalism, and socialism internationally and in the specific Latin American setting. The book ends with an extended treatment of the global crisis of 2008, with specific attention to the way it unfolded in Latin America, as well as diagnostics of the political and economic fate of the Latin American Left in the current world context.

A powerful point of departure in the opening survey of the region is the fallout of neoliberal restructuring on the region’s position within the world market, and on its internal class structures. One basic set of observations has to do with the velocious turn to primary commodity exports in the 1980s, during the heyday of orthodox neoliberalism. In agriculture, the renewed focus on exporting basic commodities transformed not only the crops being cultivated, but the social relations underlying rural life in the region. Agribusiness corporations became the chieftains of agrarian counter-reform, leading a conversion to capital-intensive mono-cropping. Older landed oligarchies were transformed into allies through close economic association with the new entrants – transnational agribusiness corporations. Soy fields – ultimately for cooking oil and animal feed – now dominate the landscapes of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Monsanto and other multinational giants predominate in these huge operations, which generate on average just one job for every 100-150 hectares under production. 80

If debates on the specific articulation of distinct modes of production within singular Latin American social formations predominated left intellectual life in the region for much of the 20th century, these have largely been eclipsed with the penetration of capitalist relations into virtually every sphere of social life, including agricultural economies. 81 If agro-industrial capital was the game-changer in the elaboration of the new dynamic, small producers were its disposable by-product. Dispossession of peasants manifested itself through increased input costs, competitive pressures, and risks associated with bumps and dips in the international market. Attempting to adapt to the novel imperatives of agro-chemical inputs, refrigeration, and rapid transportation, small producers frequently became indebted, lost their lands, and migrated to the cities, joining a growing reserve of un- and under-employed informal proletarians.

Accompanying this metamorphosis of the countryside, a new modality of open-pit mining, under the thumb of foreign (often Canadian) capital, has contributed to the sharpening of primary commodity production for external markets. 82 While the search for foreign investors in this area began in earnest in the 1990s, the pace quickened with the Chinese-driven commodities boom (2003–2011). 83 Mining expansion has been notoriously accompanied by fierce repression, indigenous and peasant dispossession, the eruption of defensive popular struggles, and environmental calamities. 84

Growth of the agro-mining complex has chaperoned the relative decline of industry. The weight of the manufacturing sector in Latin American aggregate GDP in 1970–74 was 12.7 percent, compared to just 6.4 percent in 2002–06, and the trend has not changed under progressive governments; indeed, it has often worsened. The gap between Latin American and East Asian industrial production, productivity, technology, registry of patents, and spending on research and development is cavernous and still widening. 85 But rather than industry disappearing altogether, it has been restructured in a subordinate way to the latest cycle of dependent reproduction. In Brazil, productivity has decelerated, costs have jumped, and there is scarce industrial investment in a context of rapidly deteriorating energy and transportation infrastructure. Similarly, in Argentina, in spite of small reversals in the last decade, regression of industry continues, with a move from 23 to 17 percent of GDP since the 1980s, concentration of foreign ownership, and weak links to national production of component parts. 86 The progressive political cycle of the early 21st century across much of the region has not modified Latin America’s vulnerability in the face of twists in the world market. This fragility persists, in part, because of the relative decline of industry and expansion of primary exports, and the lack of productive diversification. 87

In smaller countries in the region, remittances and tourism have become ever more important in terms of generating foreign exchange. Latin America has been transformed into the biggest regional recipient of remittances, with several countries counting this as their first source of foreign exchange – the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guayana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, and Nicaragua – and a number of others, their second – Belize, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Surinam. 88 Much of this flows from the United States, of course, where roughly 30 million documented and undocumented Latin American migrants reside. 89

Transformations in agriculture, mining, industry, remittances, and tourism have, of course, had an impact on class formation, from above and below. The profile of the dominant classes has altered, Katz contends, from one of national to local bourgeoisies. 90 The former type corresponded with industries that were involved in production for the internal market during the height of import substitution industrialization (ISI) (1930–1980), with tariff protections and subsidies privileging the expansion of domestic demand. The latter type, by contrast, is characteristic of a sector that no longer restricts itself to manufacturing activity, nor to internal markets. Instead, it is export-oriented and prefers the reduction of costs to the amplification of consumer power at home. 91 The local bourgeoisie has tightened its linkages with foreign capital, but has not disappeared as a differentiated segment. It maintains its own pretensions and strategies of accumulation, and looks beyond the national context, onto the regional scene. 92

The more successful capitalist groups of this kind have become more concentrated and internationalized, establishing regional clusters called multilatinas. These multilatinas emerged from wealthy families with familiar surnames – Slim (Mexico), Cisneros (Venezuela), Noboa (Ecuador), Santo Domingo (Colombia), Andrónico Lucski (Chile), Bulgheroni and Rocca (Argentina), Lemann, Safra, and Moraer (Brazil) – and have tied themselves to global management, and extended their priorities to a regional scale. Brazil and Mexican multilatinas are leading the pack, followed by Argentine and Chilean enterprises. 93 Although these entities are more powerful than Latin American corporations of the past, the regional capitalist class remains secondary on a global scale, and has lost significant ground to competitors in Asia. 94

As noted, from below, agrarian liberalization has led to the dispossession of the peasantry and their exodus to the shantytowns of cities, be it in their own countries or elsewhere. 95 The urban labor markets, meanwhile, have deteriorated with the privatization of state-owned enterprises, the decline of public sector employment, and the relative decline of industry. Precarity, a normal feature of capitalism historically, is extending its purview in the present phase. In a number of countries, marginalized youth have sought refuge in the burgeoning narco-economy, where they often end up contributing – in one sense, or the other – to soaring homicide statistics. 96 The extractive model of accumulation – agro-industry, mining, natural gas, and oil – creates few jobs, and what industrial jobs remain are increasingly “informalized,” through the spreading use of flexible, non-union, female workers. 97 While middle classes have enjoyed a certain expansion of their consumptive power through the extension of credit in the midst of high commodity prices, the boom over, and the fragile basis of that power is becoming increasingly visible. 98

Under most Left administrations, there has been an extension of social assistance to temper the worst of impoverishment. But the priming of cash transfers to the extreme poor was only ever a stopgap, offering no solution to the root causes of the problem. Crucially, these programs persist alongside precarity in, and informalization of, the world of work along neoliberal lines. While there has been a diminution in income inequality in the 21st century, the aggregate gini coefficient of the region (51.6) remains well above the global average (39.5), and is double that of the average in advanced economies. 99

Geopolitics and Accumulation

Geopolitical trends are intimately intertwined with these structural patterns of accumulation and class composition. What, for example, is the new role of China? As Katz suggests, there is little evidence that China represents now, or will represent in the near future, a political-military rival to the United States in Latin America. However, over the course of the early 21st century, the dominant Asian power has become a principal market for Latin America’s primary material exports, absorbing 40 percent of such sales, and an investor of growing importance, with aggregate investment rising from merely $15 billion in 2000 to an estimated $400 billion in 2017. Parallel to these roles, China has transformed itself into a critical line of credit to Latin American countries. Between 2005 and 2011, it lent more than $75 billion to Latin America, surpassing the sum advanced by the United States and the World Bank.

For Katz, however, one limit of the left turn in the region has been the failure of different countries to work together to forge more propitious relations with China. The region missed the opportunity to establish intelligent linkages with the Asian power and counterbalance the influence of the United States. Instead, bilateral agreements for credit and investment have been needlessly asymmetrical. 100 While the conditions of Chinese loans are better than those of other international creditors, they are linked to projects of mining, energy, and other raw material provision, which threaten to lock Latin America into its dependent reproduction within the world system and saddle it with increasing debt obligations. 101

The geopolitical orientation and economic affairs of the United States in Latin America are likewise difficult to pry apart. At the beginning of this century, the principal economic initiative of the United States in the region was the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which envisioned a trading and investment bloc linking every country from Canada in the north to Chile in the south, with the exception of Cuba. When the FTAA was defeated in 2005 by popular opposition from social movements and some left-wing Latin American governments (most notably, Venezuela), the United States shifted to a strategy of bilateral trade agreements with allied countries – Peru, Chile, and Colombia, for example, with NAFTA already having incorporated Mexico in 1994. These agreements forged the basis for the so-called Pacific Alliance, part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership plan. The bilateral trade signatories were all a part of the Latin American component of this plan, which would then link with 11 Asian countries in a commercial and geopolitical encirclement of China and run alongside the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) binding the United States and European Union. On the geopolitical terrain, the Pacific Alliance was intended to concretize political ties between the United States and right-wing governments in the region so as to better thwart leftist initiatives to develop counter-hegemonic regional alliances, based on sovereignty and autonomy. 102

Amid these turbulent strategic forays on the part of the United States, Brazil has assumed a vital role as sub-imperial arbiter in South America. Since it need not submit to every whimsy of Washington – the place of Brazil in the international division of labor is closer to Spain than Nicaragua or Ecuador – it has sometimes charted an independent political course. Yet the moderate leadership of the Workers Party (PT) government since 2003 sought to play broadly within the accepted parameters vis-à-vis the United States. In its relative autonomy, for example, Brazil sought to defend the expansion of its 15 largest multilatinas, often through the channels of its strategic integration project (Initiative for the Integration of the Regional Infrastructure of South America, IIRSA) and its massive development bank, BNDES.

Brazilian state managers modernized the country’s armed forces, attempted to mediate major conflicts in the Middle East, Iran, and Africa, and pursued a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. There is no other Latin American state operating with this level of regional and international power. At the same time, Brazilian governments in the 21st century have harmonized with U.S. foreign policy insofar as they have allowed American military bases to operate in strategic Amazonian junctures, and played a leading role in the collective occupation of Haiti. Meanwhile, even in areas where Brazil’s foreign policy has been relatively independent of, and in potential conflict with, the United States on one level – IIRSA, BNDES – it has often had the unintended effect of strengthening the U.S. position on another level. The clearest example in this regard is the way in which the Brazilian sub-imperial pursuit of the interests of its own biggest capitals has frequently meant the undermining of more radical integration projects, such as the Venezuelan-led Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our Americas (ALBA). 103

Antinomies of Regional Integration

Coextensive with the consolidation of Center-Left and Left governments in South America and parts of Central America in the mid-2000s were the first initiatives to construct regional counter-blocs to North American power in the region. The two most agglomerating cooperative institutions to result were the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), both finalized in 2011. While profoundly heterogeneous in its political composition – Cuba and Venezuela alongside Mexico and Colombia – CELAC, and to some extent UNASUR, represent, at a minimum, a symbolic and diplomatic blow to the United States and Canada insofar as they now rival the Organization of American States (OAS), long understood on the Latin American Left to be an extension of the American state’s institutional apparatus. CELAC specifically excludes the United States, Canada, and overseas European territories, while it ostentatiously includes Cuba 104 .

With greater political coherence than CELAC or UNASUR, but burdened with acuminate structural limitations, ALBA represented a more assertive bid for anti-imperialist unity. The incipient institutions of ALBA, first launched in 2004, were conceived as a sharper rupture with, and critique of, U.S. power, and were oriented toward the promotion of a multipolar world order. ALBA led experimentations, however limited, with trade agreements and economic associations between member states based on principles of reciprocity rather than free market norms of comparative advantage and ruthless competition. During the height of the oil boom, ALBA’s key economic projects, Petrocaribe and Petrosur, as well as its communications enterprise, Telesur, expanded rapidly, with registered impact in their relevant domains. More ambitious initiatives, such as the Bank of the South and the common currency, Sucre, never really got off the ground, and are today more or less moribund. Behind ALBA’s near total implosion in recent years looms the proximate collapse of the international price of crude in 2014; but the deeper cause was the fact that of all the member states – Venezuela, Cuba, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Honduras (withdrew 2009), Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Saint Vincent and the Grandines, and Saint Lucia – only Venezuela had any serious material resources to guarantee its reproduction. Even the Venezuelan economy, though, was not comparable to relatively industrialized economies in the region – Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico – and was thus extremely vulnerable to the delayed arrival of the global crisis of capitalism that erupted in 2008. The central mechanism delivering the global slump to Venezuela was, clearly, the fall of the oil price, the pillar of both its domestic social programs and its principal geopolitical endeavour, ALBA. 105

The Economic and the Political

Politics and economics, for Katz, have been out of sync in 21st century Latin American politics. While the two dimensions are closely related, with mutations in one always impinging on the other, they do not always proceed at the same rhythm, or even move in the same direction. 106 Politically, the Left turn disrupted elitist citizenship regimes through the democratic conquests of constituent assemblies and new constitutions in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. 107 Left governments have also allowed for maneuver room – albeit sometimes reluctantly – to social movements from below. Even a cursory comparison with the repressive regimes of Colombia, Peru, and Mexico on this score is instantly revealing. In many countries, there has been an ideological recovery of anti-imperialist traditions, and the revival of more thoroughgoing conceptions of popular sovereignty. In some countries the question of what socialism might look like in the contemporary world was at least raised, if not actualized. 108

And yet these political and ideological advances failed to translate into a transformation of class structures and Latin America’s subordinate insertion into the international division of labor. Right wing governments, such as those in Colombia and Peru, utilized the commodities boom to further consolidate neoliberal pillars of their economies. Center-Left governments, like Lula’s in Brazil and Kirchner’s in Argentina, entered into modest confrontation with neoliberal precepts, while leaving others intact. In more radical processes, such as those in Bolivia and Venezuela, greater breaches with the inherited order were put on the agenda, but rarely – and then, only partially – realized. The desynchronization of politics and economics is an expression, in this instance, of popular rebellions mitigating the frenzy of neoliberal torment, without uprooting its groundwork. They were uprisings strong enough to prevent their own routing, but too weak to mature into triumphant anticapitalist revolution. 109

For Katz, as for Marx, there are no static formulations of any empty, abstract, universal capitalism, nor of its imperialist forms. At the same time, unlike in the recent work of Borón, one will not find in Katz an autonomous, hyper-contingent sphere of “geopolitics,” with a logic exterior to the logic of capitalist accumulation. Instead, there is a historical, processual, and dialectical movement, where each analytical move introduces new determinations and mediations, as they are articulated in the totality of the intensely-complex, world-capitalist market. All of this allows for an accounting of the out-of-sync temporalities of politics and economics, even as these areas are understood to be internally related, retaining a dialectical unity.

Horizons

This has been a sketch of broad historical contours, partial notes stretching across centuries; it is not exhaustive, nor does it constitute the last word on any of the routes of inquiry into which it has wandered. This exercise has been as much about exposing potentially fruitful avenues of departure as about drawing decisive conclusions. Indigenous rebellions of 1992 were the return of Columbus’s 1492 repression. The trammelling of Andean insurgency in 1780–82, the precursor of a hollow independence in the early decades of the next century – the last day of despotism, and the first day of the same. Rich transmogrifications of “Latin America” spanned a couple of centuries – from French imperial apologia, through liberal anti-imperialism, to revolutionary nationalist “Nuestra América” and the indigenous recovery of Abya Yala. Marxism, in the meantime, marched through its distinct Latin American phases once capitalism made its entry in the late nineteenth century. Extra-parliamentary revolts of the late 1990s and early 2000s found only muted and pacified expression in the state capture of passive revolutions during the subsequent commodity boom. 110 Latin America’s “Second Independence” was closer to the first than the originators of that moniker had hoped.