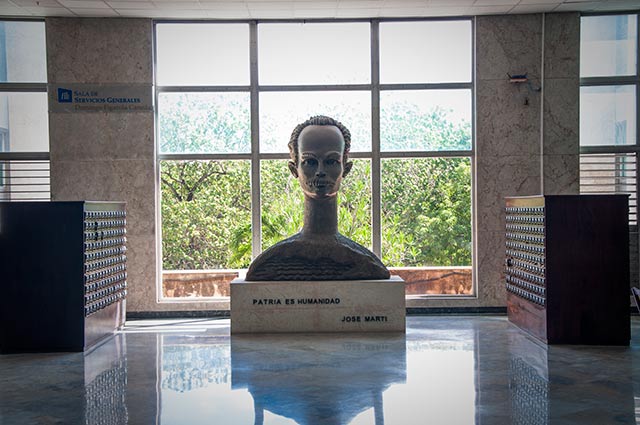

Cuba has been home to iconic anti-imperialists like the 19th-century patriot and poet José Martí, rebel leader Ernesto “Che” Guevara, to whom Cuba gave special citizenship, and Fidel Castro, whose image will always be that of the bearded rebel shaking his fist impetuously at Yankee imperialism. 1 It is no coincidence that Cuba has also been in the crosshairs of more than one imperial power almost since the Spanish first colonized the island in 1492. Most significantly, its multiple wars of independence from Spain took place in the second half of the 19th century long after most former Spanish colonies in the Americas had gained their independence and when the United States began to assert its own imperial ambitions. The Spanish-American War and the U.S. occupation and intervention during the first years of the 20th century compromised Cuba’s newly acquired independence. The 1959 revolution promised to finally break from this legacy, but it took place in the context of a rise of the Soviet Union, which, while socialist, was not without its own imperial tendencies.

This history illustrates the complex workings of imperialism, which exercises direct control over a country’s economic, social and political spheres, but also over its ideologies, laws and domestic struggles, and often in the context of multiple imperialisms. Making an analysis of imperialism even more complicated, these same imperial powers have made use of the rhetoric of anti-imperialism for imperial ends. At the same time, while anti-imperialist movements have used anti-imperialist rhetoric, in practice, anti-imperialist struggles in Cuba have looked less to disassociate themselves entirely from all imperial power and instead have focused on producing results that weaken empire, as a logic of European dominance and capitalist expansion, more generally. 2

While much of the work on imperialism has focused on distinguishing between different types of imperialism over time or between empire and imperialism, putting aside these considerations and focusing on various cases in Cuban history allows us to see certain slippages between the categories of imperialism, empire, and anti-imperialism. Two conditions account for the specific form these slippages have taken and for the specific political ends to which anti-imperialist discourse has been deployed. First, any particular imperialism operates in conjunction with other imperialisms, such that even when ostensibly at odds, they can they can in fact enable one another, both unintentionally and intentionally, since their interests are served not just by the maintenance of their empire, but by empire more generally. In 19th-century Cuba, even if one or another imperial state was actually controlling the island through direct colonial rule, other forms of imperial control often operated simultaneously and often rival imperial states privileged empire in general over their own specific imperial interests.

Second, imperialism, and, particularly, as Michael Rogin notes, its U.S. form, operates not just through control of a nation state’s land, labor, raw materials, capital and markets, but also through the colonization of domestic struggles, which, in the case of Cuba, have had to rely in one way or another on some imperial power (as a place of exile, economic support, or markets). 3 Recognizing and identifying this dynamic, however, has not necessarily provided anti-imperialist movements with an easy way to escape from this dependence. Cuban nationalists both in Cuba and abroad have long negotiated these various imperialisms and struggled, with varying degrees of success, to maintain a purely anti-imperialist position. After 1959, while the Cuban and Soviet government rejected the claim that Cuban/Soviet relations were simply a new type of imperialism, Cuban revolutionaries were still concerned with Cuba’s compromised autonomy within that relationship. While some exile groups in the United States focused their attention on Cuba’s relations with the Soviet Union, a few attempted to maintain a consistent position of anti-imperialism by criticizing both the Soviet presence in Cuba and what they believed to be the nefarious policies of the U.S. government as well as the overdependence of many exile groups on it.

In what follows, I offer a number of vignettes or moments in Cuban history that illustrate the related operations of imperialism and anti-imperialism, of the ways that anti-imperialist struggles rely upon and resist an imperialism that can never be fully opposed or pinned down, and of the various uses to which anti-imperialist rhetoric has been put. As we shall see, it has been used to preserve a racist economic and social order, to advance political independence or thwart it, to challenge U.S. domination, and to question the anti-imperialist credentials of the Cuban revolution. In all these cases, anti-imperialism could not always be so easily disentangled from imperialism as a specific practice of nation states, or the larger logic of empire, as these limited the options available to the anti-imperial struggle.

Colonial Cuba and Competing Empires

Cuba emerged as a flashpoint for competing empires soon after the Spanish conquest of the island in 1492. During the earliest years, anti-colonial sentiments and policies, especially of white Creole elites, did not reflect a rejection of foreign influence, but rather an attempt to curtail that influence without upsetting political, social, racial and economic hierarchies within the colony proper. This often meant considering the advantages and disadvantages of alliance with a particular imperial power, rather than a complete rejection of that alliance. It also meant that conflict between imperial powers often produced new anti-imperial actors.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Cuba was the most important military port for the Spanish Empire in the New World. 4 Many mark the brief British occupation in 1762–63 as the moment when Cuba’s importance shifted from primarily military/geographic to economic. 5 Though a peace treaty returned the entire island to Spanish rule in 1763, the occupation had a number of lasting effects. Cuba established mercantile relations with the British Empire, including with the North American colonies, whose own rebellion led to even greater trade with Cuba. The occupation also left behind the industrial equipment and slaves that formed the foundations of a sugar economy. Following the collapse of the Haitian sugar industry after the Haitian Revolution in 1791, decreased world sugar supplies and increased consumer demand led to skyrocketing prices that moved Cuba to center stage in the world sugar market. 6 More planters and slaves also arrived to Cuba from Santo Domingo. 7 Cuban planters worked to capture and control more of the benefits of the sugar boom, but many small producers were forced from the island as the cost of living increased and local food supplies declined. 8

The Cuban sugar industry reliance on slave labor brought in another set of actors. Between 1764 and 1868, 752,000 slaves arrived to Cuba. 9 The same Haitian Revolution that led to Cuba’s sugar boom and increased slave importation also reminded elites in Cuba of the potential for slave rebellion. There were slave uprisings in Cuba in 1826, 1837, and 1843, and whites were the minority on the island by 1841. 10 There were also increasing attacks and bans on the slave trade by some European countries. 11 All of this meant that while plantation owners were frustrated with Spain’s continued political and military presence on the island and its control of access to world markets, their rebellious impulses were tamed by the fear of slave rebellion. What they wanted, like Creole elites throughout Latin America, was “for Spain to guarantee internal security and defend the existing social order while relinquishing control over political power and economic policies.” 12

Nonetheless, changing conditions pushed some Cuban elites to consider alternatives to Spanish rule. The sugar boom sparked the rapid modernization of Cuba, which acquired powered machines, a railroad and a telegraph system by 1850 – all before Spain itself. 13 Cuba’s advances over the metropole contributed to an understanding of Spanish colonialism as offensive to standards of progress and modernity. While sugar monoculture brought modernization and prosperity, even its beneficiaries were frustrated with unwanted taxes by Spain and continued attempts to monopolize trade and public office. Moreover, many white planters blamed discussions about slavery in the Spanish Cortes in the early 19th century for slave rebellions on the island. This rejection of Spain led some Cubans, and especially the middle class, to look the United States as a better model, rather than rejecting imperial relations altogether. 14

By the early 19th century, the newly independent United States had moved quickly from colony to imperial power with particular designs on Cuba. Inspired by France’s purchase of Louisiana from Spain, Thomas Jefferson offered to buy Cuba in 1808, when fluctuating world sugar prices made Cuba a particularly desirable acquisition. 15 Spain turned down the offer but U.S. attempts to acquire the island continued. In 1823, John Quincy Adams, in a letter to the American Minister of Spain, articulated what would come to be known as the “ripe fruit” policy, citing “laws of political as well as of physical gravitation” that made Cuba’s separation from Spain and its union with the United States inevitable. 16 Proponents of a union argued that while Spanish tyranny had done nothing to enlighten the Cuban people in the ways of civilization and religion, Cuba would benefit from a union based both on the common interests of the two countries and the superiority of the United States. 17

For advocates of this union, nowhere were common interests clearer than in the area of slavery. As one U.S. Representative argued in 1852, the annexation of Cuba meant slavery would be “extended and strengthened in the United States.” 18 Advocate of annexation and Governor of Mississippi John Anthony Quitman argued that the destinies so intertwined that if the government did not act to annex Cuba, individual Americans should, and he advocated and prepared, but never carried out, an invasion of the island in 1854. 19

U.S. offers to buy the island often worked alongside the logic of the ripe fruit theory. In 1854, the United States’s Ostend Manifesto offered Spain $120 million for Cuba. Though the Manifesto lost backing when the Democrats lost control of Congress that same year, its position represented the continuing annexationist sentiment in the United States. Aware that a popular revolution in Spain was gaining momentum, the United States hinted that Spanish refusal to acknowledge the inevitable meant losing not just Cuba but remuneration for it. Given the legacy of the Haitian Revolution and abolitionist movements throughout the Caribbean, the Manifesto also put forth the possibility that it might become necessary in the future to wrest the island away from Spain if it did not agree to sell:

We should, however, be recreant in our duty, be unworthy of our gallant forefathers, and commit basic treason against our posterity should we permit Cuba to be Africanised and become a second San Domingo, with all its attendant horrors to the white race, and suffer the flames to extend to our neighboring shores, the fair fabric of our nation. 20

Acquisition was thus presented as both inevitable and necessary to save the region and Cuba from being “Africanised,” which referred not to the presence of Afro-descendent people (annexation was meant to preserve slavery, after all), but instead to their emancipation and equality, which, as the Haitian Revolution suggested, would come at the expense of white lives, white authority, and white privilege.

At the same time that support for annexation was growing in the United States, so too was support for annexation in Cuba proper. By the mid 19th century, Spanish officials’ calls to implement treaties banning the slave trade pushed more Cubans to the annexationist cause. In 1854 a decree freed all emancipados (slaves freed from captured ships but still kept under government control). All slave importers were to be fined and deported, intermarriage between blacks and whites permitted, and lieutenant-governors who failed to cooperate with authorities in locating slave traders dismissed. 21 In this context, annexation appealed to white Cuban plantation owners, who, while frustrated with the Spanish monopoly on trade and political power and attacks on the slave trade, were also concerned that independence threatened the racial-economic order on which their privileges rested.

The power of this argument was so great that Cuban pro-independence critics of annexation like philosopher and priest Félix Varela (1787–1853) and his student, José Antonio Saco (1797–1897), focused their attention on showing Cuban elites how only independence and the abolition of slavery, and not annexation, would protect their interests. Annexation, they both warned, would provoke a war between Spain and the United States or Britain and Cuban property and the racial order would be the casualty.

Neither were the first to introduce the idea of independence, in spite of Varela’s reputation as the father of it. As early as 1809, Cubans were discussing the idea of independence and organizing Creole separatist conspiracies, often involving free people of color. 22 Yet, argued Varela in 1824 in the pages of the pro-independence magazine El Habanero – which he founded while in exile in the United States – none of this had come to fruition because it was ultimately not the political principle of independence that would guide action, but instead, economic interest.

We must keep in mind the fact that on the island of Cuba, there is no political opinion, there is no other opinion but the mercantilist one. On the docks and in the warehouses, all the questions of the state are resolved. What is the price of fruit? What fees do customs collect? Will they be enough to pay the troops and employees?… The secret societies, which are so feared, have been insignificant on this point. Most of their members, after having spoken with great fervor during the meetings, arrive home and the talk stops; all that remains is the desire to continue enjoying their possessions. Only an attack on the purse can change the political order on the island, and as this is not distant (indeed it is already being felt), it is clear that the current government has much to fear. I call an attack on the purse the effects of a war where everything is a loss and there are no profits; I call an attack on the purse that which will oblige many trading houses to close, and ruin many planters, without the need of a popular movement or without the enemy landing on the territory. 23

Thus, elites would only be safe if Cuba became independent and avoided becoming embroiled in a conflict between Spain and the United States or England. It was upon the wealthy planters that an independent Cuba could depend and it would be an independent Cuba, which achieved that independence on its own, that would guarantee the security of that wealth. 24 “In a word,” explained Varela, “all the economic and political advantages are in favor a revolution made exclusively by those at home, and they make it preferable to what can be done with foreign help.” 25

Slavery – “the beginnings of so many evils” – presented another problem for Cuban planters, argued Varela. 26 The enslaved population of Cuba could not help but consider themselves deserving of the freedom that whites in Cuba so frequently invoked. Thus, the white planter classes would be safest with voluntary abolition. Varela advised:

give freedom to the slaves in such a way that their owners will not lose the capital that they invested in their purpose nor the people of Havana suffer new burdens, and the freedmen, in the heightened emotions that their unexpected good fortune will surely cause them, will not try to take more than what they should be given, and finally, assisting agriculture as much as possible so that it will not suffer, or at least suffer the least damage possible, because of the lack of slaves. 27

In this way, self-determination, anti-imperialism, revolution, and abolition would be steered by the interests of Cuba’s economic classes and would benefit them as well. The approach to these issues would be shaped by the desire to reign in and quell the desires and needs of Cuba’s Black population, who might mistakenly believe they were to take equal part in their benefits.

Saco too appealed to elite interests and to general stability in making his arguments against annexation and slavery and for independence. For instance, he argued that wage-labor was more economical than slavery and, unlike slavery, facilitated the immigration and growth of Cuba’s white population, which he valued over its Black one. 28 Saco supported Cuban independence, but rejected outright insurrection, which he thought would lead to the destruction of Cuban property and precipitate slave rebellion. Furthermore, while he opposed U.S. annexation because it risked placing Cuba in the midst of a war, and while Saco wished Cuba to be Cuban, Latin rather than Anglo-Saxon, his primary concern was with stability. Thus, he argued, if annexation to the United States led to stability, he would support it. 29

In this brief history, then, we see the ways that different imperial powers and policies worked together to enable both one another and a limited anti-imperialism as well. British imperialism in the 18th century, for instance, challenged Spanish imperialism both directly, in the form of the brief military occupation, and indirectly, by leaving in its wake new institutions, economic relations and political actors. The establishment of new mercantile relations with Britain and the United States broke the Spanish monopoly on trade. The introduction of laissez-faire ideas helped provide ideological fodder for those Cubans frustrated by Spanish domination of production, pricing, and trade. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the establishment of a sugar economy, based on slave labor, that almost immediately began to show profits, set the ground for both greater Cuban support for and fear of Cuban independence, as well as increased interest in the island on the part of the United States. While many Cuban planters were drawn to annexation to the United States, other Cubans like Varela and Saco attempted to negotiate between imperial powers. In doing so, however, they ended up defending a limited and exclusive nationalism, which, though opposed to slavery, continued to privilege the concerns of Cuba’s white elites. A stance of anti-imperialism was accompanied by the continued support for imperial and racial structures left by both Spain and England.

Meanwhile, slave rebellions and popular uprisings challenged these very orders from below. According to Afro-Cuban intellectual and historian Walterio Carbonell, it was not the political thought of 19th-century bourgeois intellectuals like Varela and Saco that provided the source of Cuban national culture, but rather these revolts that emerged out of the contradictions produced by the plantation economy, out of the conflict between Spanish and African peoples (between slave owners and slaves) and their respective cultures on the island. 30 Cuba’s most important historical protagonists were people like the free Creole artist of Yoruba descent by the name of José Antonio Aponte Y Ubarra, who drew on his experience as a retired militia head and his involvement in secret African sects to organize an island-wide rebellion in which some whites were involved. Aponte was betrayed and hanged in 1812, but the event inspired other smaller, but deadly, riots and sent scared Cuban representatives to the Spanish Cortes to argue against abolishing slavery in Cuba. 31 According to historian Leví Marrero: “Well informed about events in Haiti, Aponte took the insurrection of Guarico [in Haiti] as his model, and as persons to emulate, Toussaint L’Ouverture and Henri Christophe, self proclaimed king of Haiti, whose portrait he kept with his own and George Washington’s.” 32 People like Aponte, according to Carbonell, fought for “nationalism without slavery or colonialism.” 33

Independence and Anti-Imperialism

While Varela and Saco believed that appealing to the interests of the planter classes would best strengthen the movement for independence, divisions of class, race, and region were also the source of its lack of cohesion, and many attributed the failure of Cuba’s first war of independence between 1868 and 1878 to these same divisions. Also increasingly clear by the middle of the century was that Spain and the United States were not necessarily enemies when it came to Cuban independence, and that they were willing, to some degree, to work together to avoid that end. As a consequence, Cuban unity would become central theme in Cuban political discourse. One sees it throughout the political thought of famed Cuban patriot and poet José Martí who entered the political scene at the start of the first war for Independence, known as the Ten Years War.

By the second half of the 19th century, the Cuban political terrain had changed significantly. Opponents of the slave trade in Spain lost positions of authority and the South was defeated in the U.S. Civil War. Both events dramatically reduced the appeal of annexation for its supporters in Cuba. Some Cuban planters sought to secure their interests on the island through constitutional reforms in Spain and by seeking alternative sources of labor in anticipation of a ban on the slave trade or the abolition of slavery entirely. 34 As the appeal of annexation waned and frustration with Spain continued, independence increased in popularity in Cuba and in 1868, Cuba’s first war of independence began with Eastern planter Carlos Manuel de Cespedes’s “Grito de Yara.” Black Cubans, both enslaved and free, constituted a large portion of the Rebel Army in the Eastern part of the island. Men of color were also promoted to leadership positions, causing anxiety among some of the white Creole planters. 35

Cuban rebels benefited from their knowledge of the Eastern terrain and methods of guerrilla warfare. The cause of annexation to the United States was further weakened by the refusal of the United States to come to the aid of the rebels. 36 The rebel army also benefited from the knowledge and expertise of military generals, Antonio Maceo and Máximo Gómez, who arrived on the scene in 1875. These advantages, however, were counteracted by divisions within the rebel ranks and the leadership – differences based in region, class, military strategy and visions of an independent Cuba – and the withdrawal of support from rich Cuban exiles in New York. Spain capitalized on divisions and promised reform and amnesty to rebels who abandoned the cause. 37 On February 11, 1878, the majority of insurgent generals (Maceo declined) signed a peace treaty – the Pact of Zanjon – giving Cuba the same political and administrative laws enjoyed by Puerto Rico, amnesty for the insurgent ranks and freedom for those slaves and Asians in the insurgent ranks. 38 Both Cuban independence and slave emancipation were tabled. 39 Such an end vindicated the concerns of anti-imperialist critics of the Cuban independence movement, who worried that the privileging of formal political independence maintained the sanctity of a variety of oppressive institutions including slavery, the state, and the market. 40 So long as this was the case, Cuba would be divided and independence would be formal, rather than substantive.

These lessons were not lost on José Martí, who spent much of the Ten Years War in exile, following his arrest in 1869 for disloyalty to Spain and his departure to Spain in 1871 after being granted clemency. He returned briefly to Cuba following the signing of the Pact of Zanjon, but was soon arrested for conspiracy and deported again back to Spain. Between 1875 and 1880, he lived in Mexico, Guatemala, and Cuba. He arrived in New York in 1880, where he would spend much of the rest of his life working for Cuban independence and warning his fellow Cubans away from the various temptations offered by identification and alliance with the United States. Annexation had been one such temptation and its history provided a lesson about the link between the means of achieving independence and the end of independence itself. Like so much the United States had to offer, annexation at first glance appeared to offer Cubans the chance to share in the prosperity and excitement of the United States without the costs of radical upheaval. In 1881, he wrote:

In Cuba, the idea of annexation, which was born to accelerate the enjoyment of liberty, has changed in intention and motive, and today is no more than the desire to avoid a Revolution. Why do they want to be annexed? Because of the greatness of this land. And why is this land great, if not for its Revolution? But in these times, and with the relations that exist between the two parties, we will be able to enjoy the benefits of Revolution, without exposing ourselves to its dangers. But that is not rational: what you buy you own. No one buys anything for another’s benefit. If they give it, it will be because they stand to profit by it. 41

U.S. motives were never altruistic. A struggle for independence, insisted Martí, had also to be anti-imperialist. Any aid from other countries would necessarily compromise true independence based not just on formal national sovereignty, but on a national identity formed around common struggle, self rule, hard work, and creativity. 42 In 1888, just after slave emancipation in Cuba, newly elected U.S. president Benjamin Harrison put the issue of annexation on the table again as way of dealing with treasury surpluses and bringing in untaxed Cuban sugar. 43 That year, the Philadelphia Manufacturer, a paper supporting high tariffs, published an article opposing annexation primarily on this basis of its negative assessment of Cuba’s population. It argued that all three types of Cubans – Spanish, Creole (i.e., white and Cuban-born), and Black – had suffered the consequences of Spanish rule. The Spanish were tyrannical and corrupt. The Creole had the flaws of the Spanish, but were also deemed lazy, effeminate, and submissive. The “near million blacks” in Cuba were also deemed inferior to Blacks in the United States and annexation would put them “on the same level politically with their former masters.” 44 If past supporters of annexation had cited Spain’s failure to properly civilize its colonial subjects, including its larger Black population, as evidence for the need for U.S. guidance, the Manufacturer used this same evidence to argue that Cuba was not a desirable vassal. Anti-annexationist arguments too relied on imperialist tropes that were constantly reconfigured.

Thus, while Martí (and Cubans more generally) did not support annexation, he felt the need to challenge the Manufacturer’s negative characterization of Cubans, which, while now marshaled to oppose annexation, had served in the past to justify it. Cuban admiration for the United States, argued Martí, could not be confused with support for annexation or for a lack of critical reflection on the excessive individualism and reverence for wealth that also characterized the United States. Cubans, wrote Martí, admired the United States of Abraham Lincoln rather than that of the founder of the U.S. annexationist League, Colonel Francis Cutting. Alliance was possible but on equal terms. Moreover, argued Martí, Cuba was not the country described in the Manufacturer. Cubans had managed to survive and thrive in Cuba and in exile in spite of the damage of the Ten Years War. Just as the United States was multifaceted, with virtues and vices, and a history marked by conflict and disunity, so too was Cuba’s history marked by the failure to unify, as during the unsuccessful Ten Years War, and by disappointments, challenges and distractions. 45 Of those distractions, annexation had long served to derail and muddy the Cuban struggle for independence, providing false hope to those wishing to free themselves from Spanish control while avoiding the work and sacrifice of independence. According to Martí:

And it is the melancholy truth that our efforts would have been, in all probability, successfully renewed, were it not, in some of us, for the unmanly hope of the annexationists of securing liberty without paying its price, and the just fears of others that our dead, our sacred memories, our ruins drenched in blood would be but the fertilizers of the soil for the benefit of a foreign plant, or the occasion for a sneer from the Manufacturer of Philadelphia. 46

Even in 1895, after another war for independence from Spain had begun in Cuba, Marti feared an annexationist fate. On the eve of his death, he wrote to his friend Manuel Mercado, the Mexican undersecretary of the interior:

The nations such as your own and mine, which have the most vital interest in keeping Cuba from becoming, through an annexation accomplished by those imperialists and [my emphasis] the Spaniards, the doorway – which must be blocked and which, with our blood, we are blocking – to the annexation of the people of our America, by the turbulent and brutal North that holds them in contempt, are kept by the secondary, public obligations from any open allegiance and manifest aid to the sacrifice being made for their immediate benefit. I lived in the monster, and I know its entrails – and my sling is the sling of David. 47

The last sentence of the paragraph is frequently cited for its powerful portrayal of a monstrous U.S. Empire and as evidence of Cuba’s long history as the thorn in its side. Less often noted, however, is Martí’s observation that Spain and the United States were not necessarily at odds with one another in this endeavor to foil Cuban independence. Moreover, these empires might work together to block Cuban independence even if only one, the U.S., was to actually gain possession of the island. This was because their greater concern, suggested Martí, was to block the spread of anti-imperialist politics across the region.

Martí learned much of these designs from a New York Herald correspondent, who told him of:

Men of the legal ilk who, having no discipline or creative power of their own, and as a convenient disguise for the complacency and subjugation to Spain, request Cuba’s autonomy without conviction, content that there be a master, Yankee or Spaniard, to maintain them and grant them, in reward for their service as intermediaries, positions as leaders, scorn of the vigorous masses, the skilled and inspiring mestizo masses of this – the intelligent, creative masses of whites and blacks. 48

So too he told Martí of a conversation with the Spanish governor of Cuba, Arsenio Martínez Campos, who led him to believe that when faced with insufficient resources to continue to fight independence, “Spain would prefer to reach an agreement with the United States than to hand the island over to the Cuban people.” 49 Imperial powers preferred defeat by another imperial power than defeat by a national liberation movement that threatened empire more generally.

Of course, under these conditions, Marti’s own position was not entirely “pure,” for he too took advantage of the imperial relationship with the United States in the sense that he used the United States as a home base from which to organize and draw financial resources for the cause of independence in Cuba. Moreover, as head of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, which never was actually in power in Cuba, one might argue that his anti-imperialism could take an outwardly pure stance because it was about mobilizing popular support for independence rather than forming specific state policies. Martí died in battle the day after he penned his famous “sling of David” letter. Perhaps his early death saved him from having to compromise his pure anti-imperialist stance in the ways that those at the helm of an “independent” Cuba would eventually do.

In many ways, Marti’s fears came true, since the United States ultimately entered the Cuban war for Independence against Spain, transforming it from a war of liberation into a “North American war of conquest,” thenceforth called the Spanish-American War. 50 U.S. troops arrived at Guantánamo Bay in June of 1898 and raised the first U.S. flag. According to historian Jana K. Lipman, there were early hints in the U.S. press of the U.S. navy’s desire to maintain control of Guantánamo Bay and establish a naval base there. 51 In a decisive victory, U.S. troops occupied Santiago de Cuba on July 3, 1898 and planted their flag above the Cuban one, while Cuban troops who had participated in the fighting – and indeed 30 years of struggle against the Spanish – were forced to wait outside while the United States accepted Spain’s surrender. 52 On December 10, 1898, Spain signed a peace treaty with the United States without any Cuban representatives present, and on January 1, 1899, the United States assumed formal control of the island.

Reports to Congress on the situation in post-war Cuba echoed earlier civilizational arguments about the superiority of U.S. occupation over Spanish, but also indicated that the Spanish remaining in Cuba were amenable to annexation to the United States. According to Major General M.C. Butler, Military Commissioner to Cuba, former Spanish loyalists were far less of a threat to U.S. interests than the Cuban insurgents and their sympathizers who felt “that they made a gallant struggle for liberty and were entitled to consideration on this account.” 53 These insurgents and their sympathizers, however, needed to understand the true meaning of liberty and independence. A year later, General James Wilson, military governor of Matanzas and Santa Clara, explained to the Senate that he had “said to the Cubans”:

“You claim to have a great desire for liberty and independence.” “Liberty and independence” is their phrase. “But my friends, looking to the future, you will never have the greatest liberty and independence that you are capable of until you are free and independent to come into the American Union. That does not depend on you; it depends on us.” 54

Officials were clear. If Cuba wished to rid itself of occupying forces, it might need to abandon independence and embrace some type of annexation to do so. Indeed, American troops evacuated the island in 1902, but only after securing U.S. interests on the island through the 1901 Platt Amendment, article 3 of which famously granted the United States the right to intervene for “the maintenance of government adequate for the protection of life, property and individual liberties.” The Amendment was, in many ways, “a substitute for annexation” that “served to transform the substance of Cuban sovereignty into an extension of the U.S. national system.” 55 Cubans were faced with the choice of “a protected Republic [with the Platt Amendment incorporated into their constitution] or no Republic at all.” 56 The Amendment also required the Cuban government to “sell or lease to the United States land necessary for coaling or naval stations at certain specified points.” 57 Guantánamo Bay, then, provided the United States with a base from which to intervene in Cuba’s domestic affairs. For instance, in 1912, the United States threatened intervention into Cuba from the base in order to insist that the Cuban government suppress a movement of Cuban veterans of color, The Independent Party of Color (PIC), in Oriente. In response to the threat, the Cuban government killed thousands of the PIC’s members. 58 It thus helped maintain the legacy of respecting Cuban sovereignty only insofar as Cuba maintained the existing racial and economic order.

The Platt Amendment was a bitter symbol of the refusal of the United States to accept Cuban independence and the justification for several U.S. military interventions. Even after the Cuban government abrogated the Amendment in 1933 and the United States formally annulled it in 1934, a new Lease Agreement meant the United States continued to occupy the Guantánamo Naval Base indefinitely. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Cuba’s sovereignty was repeatedly compromised by U.S. military intervention and then other more indirect means of control.

The Cuban Revolution as True Independence?

The 26th of July Movement led by Fidel Castro that was largely responsible for the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista in January, 1959, was an organization with a broad base of support, whose members included middle-class reformers, students, workers, and those, like Che Guevara, with more openly communist and anti-imperialist views. Its main proposals included land redistribution, nationalization of public services, and political and economic reform. The new provisional revolutionary government, made up largely of members of the July 26th Movement, did not immediately begin at odds with the U.S. government. A month after it took power, a U.S. government memorandum by the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs’ Special Assistant expressed concern with “Castro and especially some of his rebel lieutenants [who] bitterly resent what they consider to have been the hostile attitude of the U.S. Government, and [who] have publicly attacked this Government and fomented Anti-American feeling,” but the memorandum also held out hope for civil relations between the two countries. 59

However, relations soon worsened as the Cuban government began to radically restructure Cuba’s economic, political, and social system through a variety of revolutionary decrees that attempted to address disparities in wealth and access to social services. Two of the most significant decrees had immediate redistributive consequences. In March, the government passed the popular Urban Reform Law, which reduced rents by 30 to 50 percent. The newly established National Savings and Housing Institute (INAV) pledged to build public housing in empty lots. In May, the government passed the Agrarian Reform Law, which put limits on the size of land holdings, nationalized with compensation land exceeding these limits,and redistributed these lands into state cooperatives and some individual holdings. 60 This was just the beginning. By December of 1959, another U.S. memorandum stated that the “continued harassment of American property owners in Cuba” could no longer be tolerated. 61 Throughout 1959, U.S. officials grew increasingly indignant and alarmed by Fidel Castro’s disregard for U.S. power and policy agendas. The Cuban revolution and Castro’s audacity in the face of U.S. Empire shocked and offended them, upsetting “the equanimity by which the United States had fixed its geo-political place in the world.” 62

This was all the more so, because while diplomatic and trade relations were deteriorating, Cuba was developing ties with the Soviet Union. The worsening relations with the United States and the increasing ties to the Soviet Union had an almost tag-team quality. Thus, even as Cuban domestic policy moved quickly to consolidate power and implement a variety of revolutionary decrees, it remained also in thrall of two larger superpowers. Cuba signed its first trade agreement with the Soviet Union in February 1960. In March, President Eisenhower, worried about the anti-Americanism of the Cuban government, commissioned the design of CIA covert operations known as Operation Mongoose. In April, Soviet oil began arriving to Cuba and a month later, Cuba and the Soviet Union established formal diplomatic relations. When U.S. refineries refused to refine the oil, the Cuban government nationalized them. This in turn was met, in October, with a U.S. trade embargo on everything except food and medicine (it was extended to almost all imports in 1962). In January 1961, the United States and Cuba broke diplomatic relations. In April 1961, CIA trained exiles were defeated at the Bay of Pigs and shortly thereafter Castro declared the revolution socialist, though Che Guevara had hinted at the Marxist nature of the Cuban Revolution before then. 63 Toward the end of 1961, the Kennedy Administration officially authorized Operation Mongoose. Finally, in 1962, in response to U.S. Jupiter missiles in Italy and Turkey, the Soviet Union installed ballistic missiles in Cuba and the United States imposed a naval blockade. Kennedy and Khrushchev reached an agreement in which missiles were removed from Turkey and Cuba. The Cuban government was largely absent from these discussions, an early reminder that revolution had not necessarily liberated the island from a legacy of being caught in the cross hairs of larger powers.

While the United States signed a non-aggression pact following the Missile Crisis, small-scale invasions through Miami based anti-Castro paramilitary groups like Alpha 66 continued after the non-aggression pacts accords were reached. U.S. policy shifted in early 1963 from supporting direct attack to fomenting revolt from inside and the United States moved the bases of operations to other countries to avoid accountability. 64 However, raids to the island continued which the CIA explicitly backed or did little to deter. Paramilitary activities continued throughout the 1960s even after the U.S. authorities grew frustrated with their unruly behavior and began cracking down on them. 65

Critics in the United States questioned Soviet claims to third world solidarity and instead suggested that Cuba was the latest casualty incorporated into its ever-growing empire. 66 The Soviet relationship, especially in the early years, was of course far more complicated.

On the one hand, it was not without aspects of paternalism, romanticism and racialization. 67 Links to Cuba also served a variety of political purposes within the Soviet Union and internationally. Support for Cuba served as proof of the sincerity of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization campaign, as a reminder of revolutionary fervor and enthusiasm in the Soviet Union, and as a symbol of the failure of U.S. imperialism. 68

On the other hand, Cuban officials from Fidel Castro to Ernesto Che Guevara characterized economic relations with the Soviet Union as advantageous and qualitatively distinct than those between Cuba and the United States. In a March 1960 speech, for instance, Guevara argued that although Cuba made its “first step” toward national political sovereignty on January 1, 1959,another key step in the process involved breaking “the monopolies stranglehold on foreign trade” by signing new trade agreements with countries seeking “the Cuban market on absolutely equal footing.” 69 Of those new agreements, he argued, the one with the Soviet Union was the most important since it provided Cuba with a guaranteed market for its sugar quota. In return for this sugar, Cuba would receive mostly manufactured products or raw materials, rather than cash, and bypass the world market entirely. While critics warned that the distance made Soviet imports expensive, the Soviet Union’s commitment to sell oil to Cuba at 33 percent cheaper than U.S. monopoly companies showed that this agreement actually offered a degree of “economic liberation.”

Guevara acknowledged that, as some critics claimed, the Soviet Union may have been using the agreement partially to “annoy the United States.” Yet, this did not then point to Cuba’s return to just another imperial relation. Guevara wrote:

The Soviet Union, making use of its sovereignty, can, if it feels like annoying the United States, sell us oil and buy sugar from us to annoy the United States. But what do we care? That’s a separate question. What their intentions may or may not be is a separate question. In our trade we are simply selling merchandise, not our national sovereignty as we used to do. We simply intend to talk on equal terms. 70

Here then, Guevara suggests that Soviet intentions were secondary. Indeed, for Cuba to concern itself too much with this question would be to privilege intentions over results, the Soviet vantage point over the Cuban one, and an ideologically pure anti-imperialism over a pragmatic one that might better preserve Cuban independence. Anti-imperialist ends mattered more than anti-imperialist intentions. Cuba could not, of course, transform the global balance of power, argued Guevara, and so to “talk on equal terms” might be the best course.

While Guevara would criticize Soviet-inspired models of economic development for Cuba during the famous great debate between 1962 and 1965, he continued to insist that relations with the Soviet Union were important. Thus, in a 1964 speech to the UN, he described the installation of Soviet missiles as “an act of legitimate and essential defense” and saw “the socialist camp, headed by the Soviet Union” as a key supporter of the Second Declaration of Havana. 71 These were public statements, of course, and do not capture the private frustrations of Cuban officials, including Fidel Castro, when dealing with the Soviets. Yet, as has been well documented, even these frustrations did not suggest Cuba’s unquestioned subservience to the Soviet Union. Cuban foreign policy in Latin America and Africa throughout the 1960s and 1970s did not simply follow the directives of the Soviet Union and indeed, especially in Latin America, ran covertly counter to them. 72 Cuban leaders saw Cuba as distinct from the Soviet Union and China and, as a consequence of this, far better positioned to understand and aid in third world struggles. As Piero Gleijeses writes:

The Soviets and their East European allies were white and, by Third World standards, they were rich; the Chinese suffered from great-power hubris and were unable to adapt to African and Latin American culture. By contrast Cuba was nonwhite, poor, threatened by a powerful enemy, and culturally Latin American and African. It was, therefore, a special hybrid: a socialist country with a Third World sensitivity in a world that, according to Castro [in 1968], was dominated by “conflict between privileged and underprivileged, humanity against imperialism,” and where the major fault line was not between socialist and capitalist states but between developed and underdeveloped countries. 73

Although the Soviet Union was not another imperial state, its position of global power and relative development created conflicts with post-colonial states, even as they tried to build socialism.

Castro’s public statements, like Guevara’s, reflected ambivalence towards Soviet authority. Even his 1968 defense of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, for instance, contained qualifications and reminders. 74 He recognized the general trauma produced by a large nation invading a smaller one and hinted at the parallels one might draw between, on the one hand, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia, and on the other hand, the United States and Cuba. While he ultimately defended the invasion in the name of protecting socialism and revolution, he did remind the Soviet Union that it needed “a consistent position with regard to all the other questions that affect the revolutionary movement.” 75 Many among the international left were disappointed by Castro’s support of the invasion, and with good reason. The point here, however, is that his support reflected the contradictory and impure politics of anti-imperialism in the context of the Cold War.

Exile and Dissident Anti-Imperialism

The dilemmas of attempting to maintain a pure anti-imperialist position have not been exclusive to the Cuban government. In light of Cuba’s history in the cross hairs of empire, Cuban critics of the government since 1959, and especially on the left, have long struggled to legitimate their nationalist credentials by asserting their autonomy from other foreign governments. Many Cubans disillusioned with the Cuban revolution found a home in Miami and, as rabid anti-communists, supported U.S. efforts to topple the Cuban government by taking out Fidel Castro. U.S. involvement, however, also compromised indigenous Cuban resistance to Fidel Castro, since it meant that counter-revolutionaries and later, dissidents, could be dismissed as lackeys of U.S. imperialism eager to return Cuba to its neo-colonial status. A consistent anti-imperialist position, then, became one way to respond to this criticism, since it could be argued that it was imperialism of all national stripes, rather than capitalism, that constituted the primary threat to Cuban sovereignty.

By the start of the 1970s, as the revolution in Cuba was institutionalized, exile plans for immediate return faded, and the United States abandoned more aggressive actions toward the island, new groups emerged of younger Cubans such as Agrupación Abdala and the collective surrounding the journal Arieto, who were critical of the older generations of exile leaders for their intransigence, corruption, and subservience to the United States. 76 As Michael Bustamonte documents, however, Agrupación Abdala was distinct in its attempt to forge “a suis generis, albeit at times contradictory, anti-communist anti-imperialism – born of détente era frustration yet drawing on Cuba’s historic nationalist canon.” 77 This anti-communist anti-imperialism attempted to hold together a number of anti-imperialist and progressive nationalist strains. Like other exile groups, they were critical of the United States for its failure to topple Castro, but unlike most other groups they traced this betrayal back to the first half of the 20th century when the United States had failed to properly respect and support Cuban sovereignty. Also distinct was their insistence that their opposition to Fidel Castro grew not out of the Cuban government’s decision to nationalize U.S. properties, but because he had established a new subservient relationship with the Soviet Union. Communism’s primary flaw in Cuba, then, was that it was imported from abroad. As a consequence, Agrupación Abdala called for the withdrawal of both the Soviets and the United States still lodged at the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay. 78 The first edition of their monthly newspaper criticized both Marxism-Leninism and Cuban exiles who had allied with the U.S. government. 79 Their anti-communism was also distinct from right-wing exiles in that it did not preclude forming alliances with civil rights groups, social democrats, pro-labor and other center left organizations whose philosophies also informed their vision of Cuba’s future economy. According to Bustamente, “Programmatic documents envisioned a future republic with agricultural cooperatives, nationalized public utility and natural resources companies, and a banking sector free of foreign control.” 80 In a sense, then, this group held something like socialist goals – even as they identified Soviet-inspired communism as their enemy. Rather than abandon hopes for political change and independence, they sought to return to the non-militant means that were also part of the history of the July 26th movement. 81

As Bustamente shows, however, combining these various threads proved difficult in practice, as the “group struggled over tactics and expediency of certain alliances.” 82 For instance, in the early 1970s, as exile violence increased in Miami, some members became involved in the activities of the Frente de Liberación Nacional Cubano (FLNC). 83 The FLNC was known for sending letter bombs, placing explosives at Cuban diplomatic missions, and other acts of terrorism in Miami and Puerto Rico. In 1976, Abdala members also attended the founding meeting of another counterrevolutionary terrorist group—the Comando de Organizaciones Unidas (CORU)—modeled on the Chilean Fascist Junta and encouraged by the CIA as a way of consolidating what they saw as an out of control collection of organizations who activities could be condoned so long as they took place out of the United States. 84 In 1985, an Abdala delegation also attended an International Youth Conference in Jamaica aimed at counteracting the youth festivals held in the Soviet bloc. 85 Though the group attempted to change the approach to exile politics, it was an articulation of imperialism – perhaps competing imperialisms – that in part pushed them farther into their irreconcilable opposition to the Cuban revolution, and into the arms of the right.

All political organizations must of course balance short-term goals with larger principles, compromise principles in the name of strategy, face internal fractures and deal with errant or breakaway members. The point, however, for the purposes of this essay, is that their attempt to maintain a pure anti-imperialism was largely impossible even as, at the level of ideology or rhetoric, it was key to their political platform. Like José Martí, Agrupación Abdala chose a rhetoric of pure anti-imperialism, but once they moved to the realm of political practice, this position became harder to sustain. Indeed, just like Marti, these exiles actually operated in part through the beneficence of the U.S. Empire.

Rather than dismissing them as merely another instance of compromised exile politics, however, we might actually understand the dilemmas of Agrupación Abdula as part of a longer legacy of Cuban nationalist and anti-imperialist ideology, which has always found itself in the difficult position of operating in a geopolitical space dominated by imperial powers. Just as for the Cuban Revolutionaries themselves, the political vision of this small group, relegated to a peripheral status, was articulated by both imperialism and the global struggle between empires. Their attempts to stake out a purely anti-imperialist position, devoid of ties with any imperial power, were impossible, and they entered into questionable alliances and enmities as a result.

As demonstrated by each of the historical moments discussed here, political hopes in a place like Cuba have never been free from the realities of imperial designs on domination or competition. One could wonder, for instance, what Revolutionary Cuba would have looked like in a world without the threat of U.S. domination, or what socialist solidarity might bring without the constraints of a geopolitical struggle between camps. Pure anti-imperialism, in this sense, only ever seems to exist at the level of ideas. The contradictions of the various independence movements and revolutions, among both supporters and opponents, show above all that if anti-imperialism is a necessary principle for radical political practice, it is neither sufficient, nor simple for those with few options. It may be a key guiding political principle, but its power as a compass must also rely on other visions, other commitments, and ultimately, a future toward which to navigate.

References

| ↑1 | The author would like to thank Alejandra Bronfman for her very helpful comments on an early draft of this article. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Hardt and Negri draw a distinction between imperialism, as the extension of nation-state sovereignty beyond its borders, and a newer “empire,” as a supranational set of organizations and institutions united “under a single logic of self rule.” See Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2000), 9. In Cuba, however, a version of this second view of empire also existed during the time of conflict among imperial powers, who believed any imperial dominance was better than none. |

| ↑3 | Michael Paul Rogin, Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2009). |

| ↑4 | Hugh Thomas, The Cuban Revolution, 2nd ed. (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 27. Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 36. |

| ↑5 | Leví Marrero, Cuba, economía y sociedad: azúcar, ilustración y conciencia (1762-1868), vol. 9 (Madrid: Editorial Playor, 1986); Pérez, Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, 37; Hugh Thomas, Cuba or The Pursuit of Freedom, updated ed. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998); Eduardo Torres-Cuevas and Oscar Loyola Vega, Historia de Cuba 1492–1898: Formación y liberación de la nación (Havana: Editorial Pueblo y Educación, 2001), 98; Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle against Atlantic Slavery (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). |

| ↑6 | Louis Pérez Jr., ed., Slaves, Sugar, and Colonial Society: Travel Accounts of Cuba, 1801–1899 (Wilmington: SR books, 1992), xiv. |

| ↑7 | Ada Ferrer, Freedom’s Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). |

| ↑8 | Pérez Jr., Slaves, Sugar, and Colonial Society, xiii. |

| ↑9 | Marrero, Cuba: Economía y sociedad, azúcar, ilustración y conciencia (1762-1868), 2. |

| ↑10 | Pérez Jr., Slaves, Sugar and Colonial Society, xv. |

| ↑11 | Denmark outlawed the trade in 1792, England in 1808, Sweden in 1813, and Holland in 1814. The United States outlawed the trade in 1808 although they continued using slaves (Ibid., xviii). |

| ↑12 | Ibid., xxi. |

| ↑13 | Louis A. Pérez, Jr., On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality and Culture (New York: The Ecco Press, 1999), 2. |

| ↑14 | Ibid., 89. |

| ↑15 | Hugh Thomas, “Cuba, c. 1750–c. 1860,” in Cuba: A Short History, ed. Bethell. Leslie (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 9. |

| ↑16 | Quoted in Leland H. Jenks, Our Cuban Colony: A Study in Sugar, Studies in American Imperialism (New York: Vanguard Press, 1928), 7. |

| ↑17 | See, for instance, Richard Burleigh Kimball, Cuba and the Cubans; Comprising a History of the Island of Cuba, Its Present Social, Political, and Domestic Condition; also, Its relation to England and the United States (New York: Samuel Hueston, 1850), 158. |

| ↑18 | J.R. Giddings, Speech of Hon. J.R. Giddings of Ohio on Cuban Annexation: Delivered in the House of Representatives, December 14, 1852. Washington: Buell & Blanchard, 1852. Slavery Pamphlets. Web. |

| ↑19 | Edmund J. Carpenter, The American Advance: A Study in Territorial Expansion (New York: John Lane, 1903), 322; Thomas, The Cuban Revolution, 221. |

| ↑20 | Carpenter, The American Advance, 323. |

| ↑21 | Thomas, The Cuban Revolution, 221. |

| ↑22 | Separatist conspiracies were organized in 1809, 1812, and 1821. Louis A. Pérez, Jr., “History, Historiography, and Cuban Studies: Thirty Years Later,” in Cuban Studies since the Revolution, ed. Damián J. Fernández (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), xxiv. |

| ↑23 | Author’s translation. Félix Varela, “Consideraciones sobre el estado actual de la isla de Cuba,” in Pensamiento Cubano, Siglo XIX, eds. Isabel Monal and Olivia Miranda (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2002), 282. |

| ↑24 | José M. Hernández, “¿Fue Varela el primer revolucionario de Cuba?” Cuban Studies 28 (1999): 70–82, 78. |

| ↑25 | Author’s translation. Varela, “Consideraciones sobre el estado actual de la isla de Cuba,” 286. |

| ↑26 | Félix Varela, “Abolition,” in The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics, eds. Aviva Chomsky et al. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 95. |

| ↑27 | Ibid., 96. |

| ↑28 | José Antonio Saco, “Párrafos de la ‘Replica a V. Vásquez Queipo en la polémica con J.A. Saco sobre el incremento de la población blanca en Cuba’ (1847),” in Contra la anexión: recopilación de sus papales, con prólogo y ultílogo de Fernando Ortíz, ed. Fernando Ortíz (La Habana: Instituto Cubano del Libro, Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1974), 100. |

| ↑29 | José Antonio Saco, “Ideas Sobre la Incorporación de Cuba en los Estados Unidos (1848),” in Contra la anexión, 96–97. |

| ↑30 | Walterio Carbonell, Como surgió la cultural nacional (Havana: Biblioteca Nacional José Martí, 2005). |

| ↑31 | Thomas, The Cuban Revolution, 91. For a detailed account of Aponte’s endeavors, see José Luciano Franco, La conspiración de Aponte (La Habana: Consejo Nacional de Cultura, 1963) and Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle against Atlantic Slavery (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). |

| ↑32 | Marrero, Cuba: Economía y Sociedad, Azucar, Ilustración y conciencia (1762–1868), 34. |

| ↑33 | Carbonell, Como surgió la cultural nacional, 35. Even in this case, however, these movements could find common cause with the British who at this point opposed the slave trade that their own earlier presence in Cuba had so strongly fueled. |

| ↑34 | These laborers included Gallegos, Canary Islanders, Irishmen, Indians from the Yucatán, and Chinese, who made up the greatest numbers. Thomas, “Cuba, c. 1750–c. 1860,” 18. In 1862, Chinese slaves made up 10 percent of all slaves and 17.5 percent in 1877. Juan Pérez de la Riva, Demografía de los Culíes Chinos: 1853–1874 (Havana: Pablo de la Torriente Editorial, 1996), 43. |

| ↑35 | Jana K. Lipman, Guantánamo: A Working Class History Between Empire and Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 21. |

| ↑36 | President Grant publicly expressed his sympathy for the rebel cause, but his Secretary of State Hamilton Fish’s desire to maintain the ripe fruit policy kept Grant’s sympathies from taking a more concrete form. Henry Houghton Beck, Cuba’s Fight for Freedom and the War with Spain (Philadelphia: Globe Bible Publishing Company, 1898), 23. |

| ↑37 | Luis Aguilar, “Cuba, c. 1860–c. 1930,” in Cuba: A Short History, ed. Leslie Bethell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 25–26. |

| ↑38 | Philip S. Foner, Antonio Maceo: The “Bronze Titan” of Cuba’s Struggle for Independence (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977), 74. |

| ↑39 | Ibid., 75. |

| ↑40 | Kirwin Shaffer, Anarchism and Countercultural Politics in Early Twentieth Century Cuba (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005). |

| ↑41 | José Martí, “Notebook 5,” in José Martí: Selected Writings, ed. and trans. Esther Allen (New York: Penguin Books, 2002), 74. |

| ↑42 | See, for instance, José Marti, “Notebook 5” and “Our America” in José Martí: Selected Writings, 73–74, 288–295. |

| ↑43 | Editorial note for “A Vindication of Cuba,” in José Martí: Selected Writings, 261. |

| ↑44 | José Martí, “A Vindication of Cuba,” in José Martí: Selected Writings, 262. |

| ↑45 | Ibid., 263-65. |

| ↑46 | Ibid., 267. |

| ↑47 | José Martí, “Letter to Manuel Mercado,” in José Martí: Selected Writings, 347. |

| ↑48 | Ibid., 347. |

| ↑49 | Ibid., 348. |

| ↑50 | Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Cuba Under the Platt Amendment: 1902–1934 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986), 30. |

| ↑51 | Lipman, Guantánamo, 21. |

| ↑52 | Ibid., 21. |

| ↑53 | Senate Committee on Military Affairs, Hearing Regarding Civil and Military Affairs in Cuba, 55th Cong., 3rd sess., January 30, 1899, 27. |

| ↑54 | Senate Committee on Relations with Cuba, Conditions in Cuba, 56th Cong., 1st sess., January 12, 1900, 24. |

| ↑55 | Pérez, Jr., Cuba Under the Platt Amendment, 34. |

| ↑56 | Aguilar, “Cuba, c. 1960–c. 1930,” 39. |

| ↑57 | Quoted in Lipman, Guantánamo, 23–24. |

| ↑58 | Ibid., 25–26. |

| ↑59 | “The U.S. Government Responds to Revolution: Foreign Relations of the United States,” in The Cuba Reader, 530. |

| ↑60 | Pérez, Jr., Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, 319–21. |

| ↑61 | “The U.S. Government Responds to Revolution,” in The Cuba Reader, 533. |

| ↑62 | Louis A. Pérez, Jr., “Fear and Loathing of Fidel Castro: Sources of U.S. Policy towards Cuba,” Journal of Latin American Studies 34, no. 2 (May 2002): 227–54, 232. |

| ↑63 | Che Guevara, “Algo nuevo en América: A la sesión de aperture del Primer Congreso Latinamericano de Juventudes 28 de Julio de 1960” in Che Guevara habla a la juventud (Ciudad de la Habana: Casa Editora, 2001), 29. |

| ↑64 | María Cristina García, Havana USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959–1994 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 127. |

| ↑65 | Ibid., 129–30. |

| ↑66 | See, for instance, “The New Imperialism,” The New York Times (August 8, 1960). |

| ↑67 | Anne E. Gorsuch, “’Cuba, My Love’: The Romance of Revolutionary Cuba in the Soviet Sixties,” American Historical Review 26, no. 2 (April 2015): 497–526, 497–98. |

| ↑68 | Ibid., 500–10. |

| ↑69 | Ernesto “Che” Guevara, “Political Sovereignty and Economic Independence,” in Che Guevara Reader: Writings on Politics & Revolution, ed. David Deutschmann (New York: Ocean Press, 2003), 101. |

| ↑70 | Ibid., 106. |

| ↑71 | Ernesto Che Guevara, “At the United Nations,” in Che Guevara Reader, 333, 336. |

| ↑72 | See Piero Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002) and Jorge I. Dominguez, To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cuba’s Foreign Policy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989). |

| ↑73 | Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions, 377. |

| ↑74 | Fidel Ruz Castro, “On the Events in Czechoslovakia,” in Selected Speeches of Fidel Castro (New York: Pathfinder, 1979), 110–25. |

| ↑75 | Quoted in Katherine A. Gordy, Living Ideology in Cuba: Socialism in Principle and Practice (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015), 94. |

| ↑76 | Michael J. Bustamante, “Anti-Communist Anti-Imperialism?: Agrupación Abdala and the Shifting Contours of Cuban Exile Politics, 1968–1986,” Journal of American Ethnic History 35, no. 1 (Fall 2015): 71–99, 78. |

| ↑77 | Ibid., 73. |

| ↑78 | Ibid., 82. |

| ↑79 | Ibid., 71. |

| ↑80 | Ibid., 77. |

| ↑81 | Ibid., 79. |

| ↑82 | Ibid., 73. |

| ↑83 | Ibid., 86. |

| ↑84 | Jesús Arboleya, The Cuban Counterrevolution, trans. Rafael Betancourt (Athens: Center for International Studies Ohio University, 2000), 153–54. |

| ↑85 | Bustamante, “Anti-Communist Anti-Imperialism?” 92. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine