Aaron Lecklider: The title of your book is Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left. Could you tell us a bit about what the book is about and in particular what the relationship is between liberation, solidarity, and sexuality?

Aaron Lecklider: The title of your book is Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left. Could you tell us a bit about what the book is about and in particular what the relationship is between liberation, solidarity, and sexuality?

Emily Hobson: The book is a history of the gay and lesbian left in the United States, centering on the San Francisco Bay Area from the end of the 1960s through the depths of the AIDS epidemic and the end of the Cold War, from 1968 to 1991. The book traces not simply gay and lesbian people who happen to be involved in broader radical struggles, but also the creation of a leftist gay and lesbian politics – efforts by activists to explain the precise relationship between sexual liberation and anti-racist, anti-imperialist, internationalist left solidarity. So, in regard to the relationship between liberation, solidarity, and sexuality: gay and lesbian leftists saw sexual liberation and radical solidarity as interdependent. First, they held that radical solidarity was incomplete without a commitment to sexual liberation. Second, and perhaps more surprisingly, they argued that sexual liberation would only be achieved by acting in solidarity with other movements to win a society that was anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and feminist.

AL: The histories of homosexuality and the left are deeply intertwined, yet these histories are often not put into conversation. What might historians of the left learn from your centering of gay and lesbian politics within that history?

EH: One lesson is that it has not only been a history of hostility or response to that hostility. It’s not only, here’s an individual person who suffered because they could not voice their sexuality in a movement that might otherwise accept difference. That’s tended to be a dominant way that people have talked about the relationship between homosexuality and the left. There are important histories to be told through that frame – the experiences of Harry Hay and others in the CPUSA, as Bettina Aptheker has written about, or of gay and lesbian radicals in the early Venceremos Brigades to Cuba, as Ian Lekus has discussed, or of gay and lesbian members of the KDP, as Trinity Ordona has analyzed. But one of the limits of that frame is that it tends to repeat the notion that the left and homosexuality are fundamentally separate and naturally in conflict. What I focus on instead is how queer radicals didn’t just work to win acceptance, but actually changed the meanings of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist struggle to incorporate sexual liberation – precisely because capitalism and colonialism depend on rigid sexual regulation. Central examples of this include gay and lesbian involvement in socialist feminism and in the Chilean and Nicaraguan solidarity movements. Probably the best known single organization or document that represents this is the Combahee River Collective, but since I am focusing on the San Francisco Bay Area, I look at other groups including Bay Area Gay Liberation, Gay People for the Nicaraguan Revolution, Somos Hermanas, and the Victoria Mercado Brigade. I also put somewhat less emphasis on theoretical statements than on practical application in organizations, campaigns, and building a political culture of the gay and lesbian left. As your work also shows, Aaron, there isn’t a fundamental opposition between the left and homosexuality. In fact there has been a queerness to the left, and queer radicals have understood that and have tried to explain that, both to other leftists who were straight and to other queer people who maybe only view the left as a site of hostility.

AL: In the book you distinguish between the gay left and “gay nation.” Can you talk about how that distinction mattered to the activists that you study?

EH: Absolutely. This is something that came up as a distinction pretty early on in gay liberation. I introduce it through the history of a fanciful gay liberationist scheme to establish what some activists called a colony in Alpine County, California, which is this rural, Eastern Sierra county, the least populated county in the state. The Alpine project was not really a project of the gay left, but rather a project within the larger gay liberation movement that gay leftists felt that they needed to distinguish themselves from. The Gay Liberation Front in Berkeley, for example, came out against the Alpine project, critiquing the language of colonialism and gay nationalism that was used by Alpine project backers. One of the reasons they were critical of that language was because that language tended to assume the gay community was a monolithic whole that was principally white, middle class, gay men. They also shared a critique of gay nationalism as being separatist and aligned with capitalism. It’s important to know that this critique was developing at the same moment that the Black Panthers were becoming much more clearly invested in socialism, internationalism, and multiracial coalition building. There were a broad range of leftists moving away from more simplistic nationalism. So gay leftists rejected the idea of a gay nation crystallized around white, middle class, gay men who were understanding gayness through their own experience but not as intersecting with the struggles of people of color, of women, of trans folks, of working class people. Another critique that was raised was that gay nationalism aligned with U.S. nationalism and liberal rights. Gay nationalists would say things like, “we are just like everyone else in the United States and what we want is equality in rainbow hue,” rather than, “we want a fundamental, wholesale transformation of society that might not even look like a nation, or the U.S. nation as we have already understood it.”

AL: One of the most interesting features of your book is the way you bring together transnationalism, which is primarily a scholarly intervention, and internationalism and anti-imperialism, which are political movements. Can you talk about that relationship?

EH: As you described, internationalism is something that gay and lesbian leftists were pursuing, and specifically in the context of the Cold War. Transnationalism is a scholarly approach that I use to try to think about the political and social exchanges that were happening across borders, particularly in the chapters where I deal with lesbian and gay involvement in the Central American solidarity movement. I try to use a transnational approach to look at multiple sides of one conversation. Gay and lesbian leftists understood themselves as residents, and usually citizens, of particular nations, working in cooperation with each other to support the self-determination of particular national liberation movements. This became especially important in the Central American solidarity movement, for example, where people in the United States were working with Nicaraguans who were part of the Sandinista revolution. The Sandinista revolution was a national movement that was meant to represent the Nicaraguan people. So you saw citizens of two clearly defined, bordered nations working in cooperation with each other. But, through solidarity activism, they created a kind of exchange that kind of superseded those borders and was more transnational. Transnational and not international, because it included people in the Central American diaspora, such as Nicaraguan exiles, who were living and working outside Nicaragua; as well as U.S.-born solidarity activists who traveled to and lived in Nicaragua; and Cubans, Mexicans, Canadians, Europeans, many others. And also transnational and not just international, because they were opposing a contra war that linked the U.S. government with the right wing in Nicaragua, in the Nicaraguan diaspora, in Honduras, and so on. Both the left and the right in this conflict operated beyond national borders, even while the Sandinista Revolution was defined as a program of national liberation.

AL: And does that link up with an anti-imperialist project?

EH: Absolutely. Activists expressed a left internationalism that was critical of various kinds of imperialist projects, but in particular for activists in the United States, critical of U.S. imperialism and of U.S. support for other legacies of imperialism. Imperialism was defined fairly broadly, to include things that in our more contemporary language we might define more as globalization.

AL: One of the locations that recurs in your book is solidarity work around Nicaragua. Can you talk about why that becomes such an important locus for the gay and lesbian left?

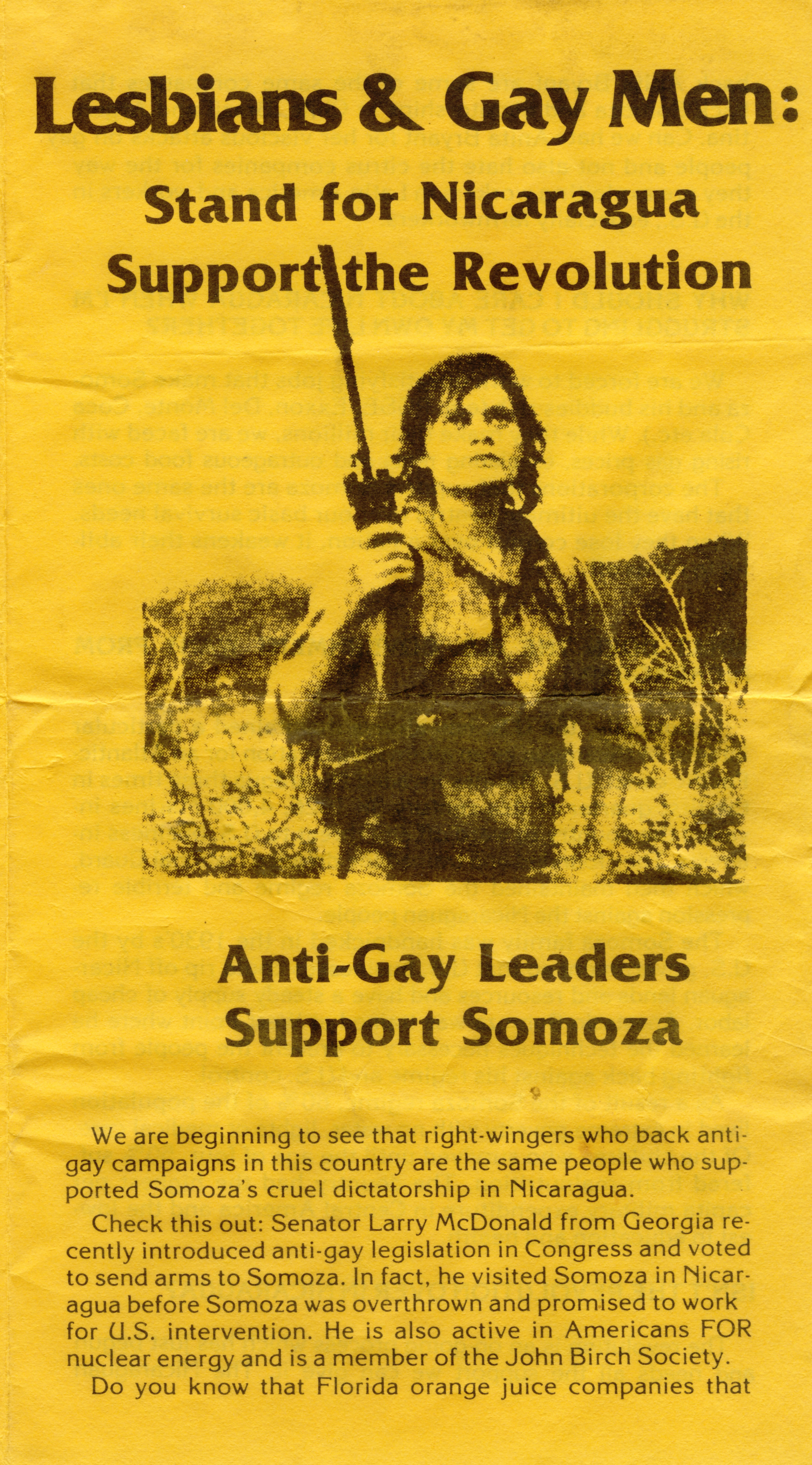

EH: One reason is simply the longevity of U.S. intervention in Nicaragua and Central America more broadly, in particular across the late 1970s into the 1980s. Another reason is the overlap between U.S. politicians supporting intervention in Central America and those U.S. politicians opposing gay and lesbian rights – in general, the Reagan administration, but even before that, figures such as California State Senator John Briggs. As the 1980s continued, these politicians continued to oppose extensive government research and funding to combat the AIDS epidemic. The United States was funding Nicaragua’s contra war: sometimes openly, sometimes secretly. And the same politicians who were supporting the contra war and opposing the Nicaraguan revolution were going after gay and lesbian rights, and pushing economic cutbacks, pushing all kinds of anti-feminist goals. A third reason that Nicaragua is important is because of the book’s overall focus on the San Francisco Bay Area, where Central American solidarity became particularly important to gay and lesbian movement. The Bay Area was home to large numbers of Central American immigrants and refugees, and the first Nicaraguan solidarity organizations in the United States started in San Francisco, specifically in the Mission District. The Mission District is right next to the Castro, which was becoming an increasingly important site of gay men’s life. Further, the Mission District itself was becoming an important site of lesbian feminist community, which included many white, lesbian feminists, and of gay and lesbian Latino and Latina community as well. So there was a direct overlap happening in the neighborhoods. For gay and lesbian people, to become involved in Central American solidarity was to take action on an international issue; on a national issue, because of the role of the Reagan administration; and on something that was very local, to build the kind of multiracial community that they imagined gay and lesbian community could be. Central American solidarity became, in part, an effort to bridge some of the gaps, differences, and tensions that were emerging between what was represented to be – and often was – a primarily white gay and lesbian community, and what was represented to be an inherently straight Central American or Latinx community.

AL: What would you want readers with an interest in anti-imperialist movements to take away from Lavender and Red?

EH: Queer radicals, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, were thinking about imperialism and anti-imperialism at multiple scales. One of the connections that gay and lesbian leftists sought to build between sexual liberation and internationalist solidarity was to think about empire not only as a tangible, measurable, boundaried, political and economic relationship, but also as a metaphor for thinking about many kinds of oppression, including oppression at the level of the body. They were often describing layers or scales of imperialist relations that would be between nations, by way of economic systems, and also something that you could see at the level of urban neighborhoods, something you could see at the level of people’s individual bodies, or our own relationships with our bodies, and even within our sex lives. Although the metaphorical approach can have its limits, such that it can be stretched too far or used too loosely, it has tremendous mobilizing power.

I think in broad terms one of the lessons that I began to realize about the book as I was finishing it, was that one of the things the gay and lesbian left tells us is that identity can be a powerful medium for change. Both left critiques of identity politics, and feminist and queer critiques of rigid conceptions of gender and sexual identities, have made many of us reluctant to claim identity as powerful. Of course identity has to be understood as changing, and rigid definitions of racial, sexual, gender, or class identities have to be taken apart. But at the same time we can’t deny that the gay and lesbian left, and many other social movements, have gained power precisely from their continual reworking of identity. The gay and lesbian left did the exact opposite of claiming one single identity as most important, or as isolated from structures of race or gender or class. They redefined gay and lesbian identities, over and over again, through solidarity with other causes. They pushed people to think about why a wide range of causes, including possibly distant causes, really mattered to them at an individual level. For those of us who are interested in building social movements, we have to begin by drawing people in. My book is a history of many different organizations and campaigns, some of them really small. But it’s also a history of how those organizations and campaigns were part of a far-reaching political culture, a whole network of music and bookstores and political posters and poetry readings – bad poetry and good poetry. That, to me, reflects the utility of thinking about imperialism from so many multiple scales. No matter how smart an analysis of an economic policy or political relationship, it’s never going to hold emotional resonance, or draw in people who aren’t politically experienced, as a political culture that helps us understand how radical change can transform our own lives.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine