We asked several contributors to write on the theme of the state and revolutionary strategy, for a roundtable discussion revolving around the following prompt:

“In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the socialist movement spilled a great deal of ink debating the question of state power. Lenin’s work was perhaps the most influential, but it also provoked a wide range of critical responses, which were arguably equally significant. But whether or not Lenin’s conception of the correct revolutionary stance towards the state was adequate to his own particular historical conjuncture, it is clear that today the reality of state power itself has changed. What is living and what is dead in this theoretical and political legacy? What would a properly revolutionary stance towards state power look like today, and what would be the concrete consequences of this stance for a political strategy? Does the ‘seizure of state power’ still have any meaning? Does the party still have a place in these broader questions?”

This essay is one contribution to the roundtable. Please be sure to read the others: Geoff Eley, Panagiotis Sotiris, Jodi Dean, Nina Power, Immanuel Ness.

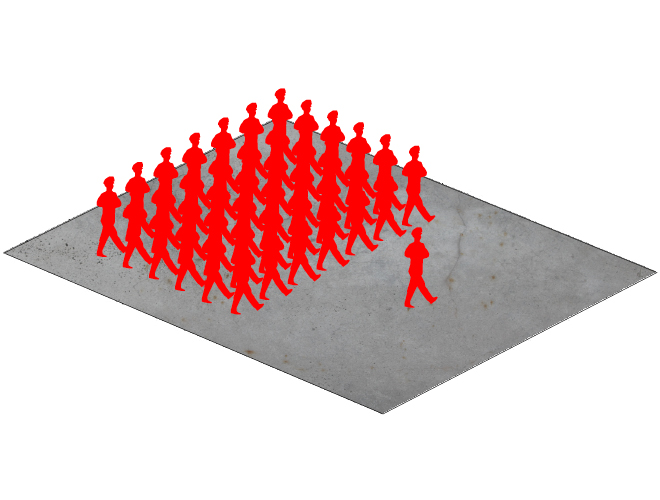

As a prefatory aside, it seems worth averring that, while we often encounter the suggestion that purportedly practical questions like that of state power are shortchanged at the expense of sexy but vague musings on revolution and full communism and so forth, in truth contemporary social movements are altogether far too focused on the state. It would be curious indeed to suggest that the various social movements and uprisings of the last few years, spilling from the squares and plazas of Egypt, Greece, the United States, Turkey and beyond, somehow did not sufficiently orient themselves to the state and its functions, whether legislative, repressive, or bureaucratic. Indeed, these movements were often entirely focused on state power – on the tyranny of leaders, on the repression of the police, on the bad decisions of parliaments and legislature. If they were thoughtless about anything, it was capital; the organization of our lives by work and money remained far more elusive as a target for these movements than the presidential palace or the department of interior. This was true from the level of the most common daily conversations to that of the most militant direct actions: again and again the state provided the focal point for these struggles and the limit of their imaginings. It is therefore in no way self-apparent that thinking more about the state, even if one promises to do it differently, is the sensible remedy for the problem of social movements that hurl themselves repeatedly against the colonnades of the National Assembly. If we are to confront practical problems in the struggle to remake the world, we should like to see the situation right side up. For us, the problem is not how to seize state power but how not to be seized by it – how we might elude being hailed by the question of power rather than that of social reproduction, and in turn, elude being forced to fight on terrain that is unfavorable.

The Unity of the Political-Economic

No doubt one must have some serious account of the state so as to avoid being captured by it. Let us in fact grant that questions of the state are of such significance for communism that they ask us to return to first principles. As it happens, it is precisely the nature of first principles that distinguishes a Marxist approach from others: they are necessarily not based in formalizations, theories, or examples drawn from the past. They are not to be found in politics. Neither, however, are they to be found in economics, in the sense of a bourgeois description of the market’s operations. Marxism being neither a policy nor a program but a mode of analysis, the return to first principles insists on unfolding the possibilities that inhere within a given historical situation. Within such an analysis, the political and the economic cannot be separated into independent strata, for it is precisely their enforced unity – the domination of political economy – which provides the character of history under capitalism and is thus the object of critique. The state ought not be rendered as a mere epiphenomenon of economic interest; neither can it be treated as a political instrumentality.

The state is a precondition for a capitalist economy, producing the legal conditions for the dissemination of property rights (and rendering the violence of property impersonal, by making the direct violence of the state something external to property rights), engaging in infrastructural projects necessary for accumulation, establishing the monetary and diplomatic conditions for exchange both nationally and internationally – most significantly, perhaps, in the production of money economies via taxation and military waging. By the same token, a capitalist economy is a precondition for a modern state (which can only fund its massive bureaucratic and military operations by way of the kinds of revenue generated by capitalist accumulation processes). Here we draw largely on the “state-derivation” debate and its reception by the writers associated with Open Marxism, the considerable nuance and complexity of which we can’t describe in any detail here. 1 In nuce, rather than treating the state as an instrument of class rule, or a semi-autonomous “region,” the writers involved with the debate examine how the functions and structures of the capitalist state are presupposed by the underlying capitalist mode of production, which itself presupposes the existence of a state. The recognition of this mutual presupposition – that is, the “form-determination” of the capitalist state by capital – is what led Karl Marx to conclude, in the wake of the Paris Commune, that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.”

This critical unity of the political and the economic does not exist in the mind, in theory, before it exists materially; neither can it be divided by any act of mind without affirming the political and the economic as the bourgeois reifications they so often appear to be, as the names of academic departments, for instance, or sections of the bookstore. When we say that communism is the real movement which abolishes the present state of things, the very condition of possibility for such a scandalous claim is that “the real movement” (die wirkliche Bewegung) draws together the visible forms of political activity with the deepest dynamics of capital, the ceaseless expression of the law of value, the ongoing restructurings of the wage-commodity nexus, the recompositions of class belonging and of technical and social divisions of labor, and so forth.

Paradoxically, it is this mode of analysis which offers a practical outlook onto strategies and tactics – precisely because questions of the state have salience only in so far as they are posed in relation to present conditions. This is the conjuncture in which people “make their own history” but only “under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” Wary of veiled idealisms, we cannot start from a political theory of the state absent this careful engagement with circumstances existing already for us. If we are to examine the extraordinary developments of France in 1871, of Russia in the early 20th century (or for that matter of China in 1949, Mexico in 1914, or any other false dawn in the long night of capital), it is not to learn from these moments what an ideal state might be. It is rather to understand from the present prospect what was possible within the given conditions, what was not, and how that might inform the question, what is possible in our own given conditions? For that is the only place from which to begin: with a careful assessment of the present situation.

Method in the Present

The debate as to whether long-standing Marxist ideas about the state, for instance, or its conceptual supplement, the party, are presently a plausible model of communist struggle will be by now a familiar conversation to some. To revisit a recent argument in which we have shared regarding the party, that might apply as well to state, “The collective experience of work and life that gave rise to the vanguard party during the era of industrialization has passed away with industrialization itself. We recognize as materialists that the capital-labor relation that made such a party effective – not only as idea but as reality – is no longer operative. A changed capital-labor relation will give rise to new forms of organization. We should not criticize present-day struggles in the name of idealized reconstructions from the past. Rather, we should describe the communist potential that presents itself immanently in the limits confronted by today’s struggles.” 2 Ideas about the state must also be adequate to their time.

None of this is to foreclose a discussion of the state or the party but to make sure we do not fall into kitsch formalisms and instead begin from solid ground. We must end there as well. By this we mean to specify the content of particular struggles, their orientation or disposition. As we know, a riot or a strike may be anti-capitalist or anti-immigrant, just as a neighborhood assembly may be convened for the purposes of instituting communist measures or protecting the property of petit-bourgeois shopkeepers. We can only evaluate forms such as the state or the party in the light of particular contents, and those contents are always given by history. However, because capitalism obtains a certain dynamic historical consistency, based around axiomatic elements – value and wage, abstract labor, and the impersonal domination of the state – communism as the content of proletarian struggles obtains a similar consistency, defined as the negation of all these elements and their replacement by a classless society. In other words, this content should not be thought of as invariant (to use the term given to it by some ultra-leftists) except to the extent that capitalism and the condition of the proletariat is itself invariant, vested in the formal and apparent separation of state and economy which occludes their compelled underlying unity.

The content of communism cannot be associated with a particular form, be it of party, council, state. It is found in the smashing of said unity-in-separation: the breaking of the index between one’s labor and one’s access to the social store, and the concomitant abolition of state and economy both. In this we discover the emancipation of proletarians from capitalist domination, the generation of a classless and therefore communist society, the destruction of all the poisoned inheritances of capitalism: wage, money, value, compelled labor, and yes, the state.

What remains contingent and historically determined is how this happens. Each age gives rise to its own communist horizon, one that unfolds from within the material conditions at hand. The horizon only seems not to move; it is historical contingency all too often mistaken for invariance by Marxists and other communists.

The Two Seizures

None of this means we can neglect the question of forms or their effectivity. If we want to know whether the “seizure of state power” thematic has relevance today, we still must understand the history of the state as particular social form, as well as the kinds of things socialists and communists have tried to do with it. To speak in the broadest terms possible, we might say that, among those who imagine the state as means to a socialist or communist end, who think of the state as an object to be seized, there are two currents of thought. One is progressivist, gradualist, reformist. The other is strictly insurrectionary. The former imagines the capture of the capitalist state through the formation of proletarian electoral majorities (and the struggles for democracy and suffrage that this presupposes) and from there a transition to socialism, perhaps involving armed confrontation but mostly unfolding within the framework of the bourgeois state. In this project, there is no immediate or complete expropriation of capitalist producers, but rather the introduction of gradual set of reforms – abolition of inheritance, nationalization of banking, progressive taxation – that aims to slowly squeeze out capital, perhaps by the expansion of a state-owned sector. We can associate this particularly programmatic conception with the practice of the 2nd International, if not its theory. The other current descends from the 3rd International, based upon a reading of the insurrectionary lines in Marx’s and Engels’s theory, particularly The Civil War in France. It is exemplified and perhaps systematized first and foremost by V.I. Lenin’s State and Revolution. Here, the state is a tool of the insurrectionary class, to be purged of its most loathsome aspects – the army, first and foremost – and used both for the administering of society along communist lines and for defensive combat against the organized enemies of the revolution.

In practice, these two currents often run together. Each can be tracked upstream to the same wellspring via a selective reading of The Communist Manifesto. Marx and Engels themselves did not seem to see any contradiction between urging, on the one hand, the need to smash the repressive machinery of the state in a revolutionary overcoming, and encouraging, on the other, the participation of workers’ parties in parliamentary processes toward winning vital reforms. The currents separate quickly, however, and most followers have emphasized one or the other; it’s not hard to read the ebb and flow between the two currents as a moving index of revolutionary promise.

The confluence of the currents is not only at their source. It returns downstream, as it were, in the courses that the two streams are driven to take in their flowing – until the two streams cross, not simply a confluence but a chiasmus. The state seized within a reformist mode, if it is not to fall back into capitalism, is compelled to move toward revolutionary expropriation; the insurrectionary seizure of the state will be drawn toward reformist arrangements.

Reformist Seizure

Let us consider this crossed destiny in some detail, beginning with the somewhat more easily dispatched reformist conception. Consider what it means to say that the modern state presupposes the existence of a capitalist economy. At the most basic level, this is a simple acknowledgment that a modern capitalist state requires continuous revenue at volumes that only an expanding economy can generate: to pay its workers, to build infrastructures, to provision armies and police, to act as a lender of first and last resort, to maintain a felicitous monetary environment for domestic and international exchange. The presupposition is mutual, since these necessary activities cannot be undertaken by individual capitalists without eroding their competitive prerogatives. The state is therefore both a requirement for, and dependent upon, conditions of profitability. 3

Moreover, if programs of redistribution and provision of a social wage – health care, education, wage controls – are undertaken while maintaining capitalist production, as one would expect from even the most feeble of social democracies, such a state will need further revenues. If it is to generate enough taxable income to pay for all its programs, it will be compelled to steer the economy toward maximal rates of surplus value generation so as to satisfy the conditions of profitability that capitalists demand if they are to keep reinvesting their income. Notably, any attempt to redistribute output away from capital and toward workers – via the mechanisms of the state – will threaten the circuit of valorization and realization, except in very exceptional conditions of high rates of profit. Such a state will be functionally subordinated to world capital, to the world-market, and the prevailing conditions of profitability and competition. None of the obvious expedients here are likely to help all that much – partial nationalization of “vital” industries, for instance, capital controls, progressive taxation.

Here we encounter the historical aspect of such a process. The mutually-presupposing functions at play in capitalism – abstract labor, money, capital, wage-labor, the state – are continually reproduced in a dynamic, historically variable manner. They have a directionality that corresponds with the tendential aspects of the accumulation process: real subsumption of labor, the rising organic composition of capital, the falling rate of profit, the expulsion of living labor from the production process. In this section, as ever, we are not describing “the state,” for such is meaningless. We are describing an exceptional developmental route. The path we have just outlined is a best-case scenario, as it were, available only to states controlling rapidly industrializing and modernizing economies capable of generating the rates of growth that allow states to meet all their socialist obligations without imperiling reproduction. In fact, industrializing economies are able to benefit in some circumstances from the kinds of putative socialist measures that reformist programs would want to enact: either social wages or direct wage controls, both of which can increase profitability. But few states are in such a position today, and those that are will quickly find themselves in the same post-industrial doldrums through which the United States, Europe and East Asia presently drift. This speaks rather clearly to prospects for Syriza-style left parties and so-called Latin American Socialism both. Such projects – and here we come to the rock and hard place of a serious analysis – will either be re-incorporated and tamed by the capitalist world system, or will need to pass over into an explicitly revolutionary, expropriating phase.

Revolutionary Seizure

We are left, then, with the “orthodox” position on seizure of state power. The state is taken up as a weapon wielded by an expropriating proletarian revolution, a weapon necessary, according to the influential treatment by Lenin, in order to smash the armed force of the counterrevolution and fulfill the administrative duties of a nascent non-capitalist economy.

Lenin’s book is an explication of the conclusions that Marx drew from the experience of the Commune, pivoting on the passage cited earlier: “ the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” Lenin educes a fairly crude conception of the state. It is a two-headed monster: bureaucratic and military. The latter he deems unsuitable to the aims of proletarian revolution; any successful overthrow of state power would need to shatter the police and army and replace them with the “armed people” or the “armed workers.” Many of the most significant revolutionary events have occurred against the exhaustion and even defeat of the state’s military powers via interstate conflicts. This confirms the importance of dismantling the repressive powers of the state; if there was ever any doubt, the recent experience of the Egyptian revolution reminds us of the army’s intransigently counterrevolutionary character.

In Lenin’s account, once the repressive fraction of the state is smashed and the legislature abolished, the administrative remainder can be made into an effective tool for those who want to produce communist or socialist relations. The necessary staff positions can be transferred quickly to proletarians and, through routinization, made simple enough that no special skills are required for their performance. But this cleansed state is not simply an “administration of things”; it is not simply the post offices whose powers of efficiency he extols. It is also, for Lenin, a “government of persons,” a means by which proletarians govern themselves forcefully, as can only be the case once we consider that, as Lenin tells us, “human nature… cannot do without subordination, control, and ‘managers.’” What matters, for Lenin, is who rules: “if there is to subordination, it must be to the armed vanguard of all exploited and laboring – to the proletariat.” 4

Government of persons is costly, however, and can’t be self-managed, distributed throughout the entirety of the social body. It requires centralization and centralization requires that no small amount of social surplus be directed toward state functions. Since these large, bureaucratic states will require massive volumes of revenue in order to operate, inasmuch as money relations are maintained they will find themselves require to develop the productive forces of the economy, to force the accumulation process forward, with all the baleful consequences this spells for presumed beneficiaries of such a revolution. Even where some of the main elements associated with capitalism are suspended, as was the case with the USSR, revolutions will find that state functions inherited from capitalist states are not good for much else than superintending a course of economic (and nationally-delimited) development, and that what one gets with these kinds of experiments in “socialist transition” is a mimesis of capitalist accumulation, using various bureaucratic and administrative indices in place of the mediations at work in capitalism. This is the best-case scenario, of course, presuming that there is an economy to develop, an assurance that seems less and less the case in the world at hand. In short, states are good for one thing: administering capitalist economies. Those revolutions which would keep in place money, wages, markets and other aspects of capitalism, in order to deal first with the question of political power, to win the war, to develop the productive forces, or any of the various reasons usually given, will find the state a useful tool, no doubt. But this is a tool that will use these revolutions with far more ruthlessness than they will use it. These revolutionary processes will therefore, sooner or later, slip back onto a historical trajectory not all that different from the reformist and gradualist path.

21st-Century Prospects

We can agree, as seems universally acknowledged, that any authentically expropriating revolution will need to arm itself and defend itself against attack. However, the “armed people” is something other than a state. Indeed, it is definitionally the opposite of the state, as it distributes and concentrates power in the hands of the insurgents themselves rather than some delegation. The more state-like such armed groups become – that is, the more they function through structures of discipline, command, hierarchy – the more they will bear in themselves the germ of counterrevolution. When the defensive power of the “armed people” is vested in a particular, dedicated fraction, directed by military leaders, it is easily co-opted, neutralized, or turned against the people themselves. Whatever benefits traditional command and control military structures might confer to those who want to win this or that battle is overshadowed by the fact that such structures, by definition, lose the war. Here, also, the historical dimension is paramount. We are not dealing with 19th-century militaries. The hyper-technological powers of killing and counter-insurgency at the disposal of contemporary states puts paid to any idea of winning a frontal confrontation, of a purely “military” victory. Even the old theory of guerrilla warfare, which has had scant success beyond peripheral, rural zones, now appears ludicrous in the face of the new algorithmic security and military apparatus that inventories every sparrow falling and every grain of sand.

Only a process of demoralization and destabilization of the armed forces, with mass defections and an undermining of the very social and economic foundations of the military, could have any hope of success. This can take place only under conditions in which the revolution is not merely a question of power, of the seizure of power, but is something that allows people to directly and immediately meet their own needs – for food, housing, and useful things; for care of all sorts; for education; for hope in the future and meaningful participation in the things that concern them. For this reason, endeavoring to lead the majority of people forcibly toward a future they don’t know is good for them – one definition of “dictatorship of the proletariat” – will always fail. If there is a role for a dedicated, interventionist proletarian fraction within the revolution, it is in creating the initial conditions under which communist relations and further communist measures might be undertaken. This might involve an inaugurating communist measure – for example, expropriating and distributing necessary and useful things on the basis of free access, or collectively and voluntarily organizing and generating other useful things. But this is something quite different than telling people what to do or commanding and organizing the activity of the larger mass of dispossessed people; such a class fraction is a catalyzing factor, producing communist relations in which it plays no part aside from its initial contribution. 5 As we and many of our contemporaries have argued, the immediate establishment of these new social conditions, to the greatest extent possible, is in the present not only the likely course a revolutionary unfolding might pursue, directly or indirectly, but, given the objective material conditions, its only hope for eventual success. 6

The question then becomes, if our task involves the immediate transformation of social relations, the abolition of money, wages, and compulsory labor, how useful would the offices, resources, and technologies of the administrative rather than repressive portion of the state be? Not very. As elaborated above, the state bureaucracy provides functions which are necessary or at the very least helpful for the reproduction of capitalism in many and various ways. States are concerned with maintaining the legal conditions of property and exchange, maintaining a proper monetary environment, providing the infrastructure necessary for the development of capital (and not the development of human beings). They help insure that labor-power arrives at the site of production in the right packaging, requiring certain conditions of hygiene and education.

Moreover, while these functional components of the state might have once enjoyed a certain autonomy from capitalist logic and market imperatives, they have been increasingly disciplined over the last century to capital’s needs, cleansed of all aspects that elude the calculative logic of the bottom line. It’s fairly fantastical to imagine that the Departments of Housing and Urban Development, of Education, or of Health and Human Welfare – along with their municipal and state-level counterparts – can be reconfigured to meet the kinds of needs for housing, learning, and medical care that people are likely to have in a revolutionary situation, without relying on the mediations of money, wages, et cetera.

From the outset, these departments are constituted by their separation from all sorts of functions pertaining to education, housing, and health undertaken directly by capitalist firms; by design, they are constitutively incapable of administering the totality of functions people would need, even in the event that such functions and capacities already exist and do not simply need to be generated from the ground up, which is the more likely scenario. The resources of the Post Office that Lenin treated as prime example of the virtuous aspect of the state may, in fact, be useful to a revolution, but no more useful than the technologies for moving objects and distributing messages that exist in the private sector. In any case, revolutions will doubtless need to invent entirely new methods of coordination and administration more suited to the tasks at hand. These functions will be most effective when directly controlled by those involved in them, whether as providers or receivers or both; in this sense, there will be no division between the state, as a sphere of separate powers that stands apart from and controls society, and no division between “economy” and “state.” There will not even be an economy, since that also presumes such separation.

Readers will recognize in this final turn the reappearance of our opening theme, having gone through its dialectical unfolding. Under prevailing conditions, which yoke the political to the economic at the root while presenting each superficially as autonomous objects, one simply errs in imagining there is such a thing as “the state” which can be supposed independent of capital’s presuppositions. The task before us is to break the domination of political-economy as such – this is the minimum definition of emancipation from capital, which engenders that unity even as it enforces its spectral separation. And this cannot be done other than by smashing the underlying unity in reality. The breaking of this bond is recto to the verso of breaking the index between labor and access to social goods, since it is precisely this indexing which makes labor the measure of value and wage the instrument of control, and thus allows the law of value and its compulsions to stand over social existence.

We can say again therefore that this breaking of the index is the goal provided to us by capital, which universalizes the index in the first place; it is in this historical sense that it becomes the project of the struggle for a classless and free society. And with this cleavage, “the state” and “economy” will be neither perfected in their independent existence nor bound together more effectively, but will cease to be; provided the autonomy in reality that they appear to have in bourgeois ideality, they will lack the mutual presuppositions that have to this point preserved them. There will simply be people meeting their own needs and developing the facilities and resources to do this.

References

| ↑1 | See Chris O’Kane’s article in this same issue for an excellent overview, as well as the introductory essay in John Holloway and Sol Picciotto, eds., State and Capital: A Marxist Debate (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979), and Werner Bonefeld’s overview “Social Constitution and the Form of the Capitalist State,” in Open Marxism, Volume 1: Dialectics and History (London: Pluto Press, 1992), 93-132. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Joshua Clover and Aaron Benanav, “Can Dialectics Break BRICS?” South Atlantic Quarterly 113 no. 4 (2014), 743-759. |

| ↑3 | The capacity of states to take on debt in conjunction with their control over the money supply can mitigate the limits imposed by the profitability of the underlying economy – for a period, per the beleaguered descendants of Lord Keynes, or indefinitely, in the perfervid promises of modern monetary theory. And yet, as we’ve seen from the monetary crises of numerous states, the underlying economic conditions assert themselves sooner or later, and states that adopt these measures recklessly risk destabilizing their currency or jeopardizing their access to credit markets. |

| ↑4 | V.I. Lenin, State and Revolution, (International Publishers, 1943), 42-43. Notice the grammatical slippage here, the appositional substitution of the vanguard for the class. It is still not ultimately clear that this is what Marx meant by dictatorship of the proletariat or how he conceived of the worker’s state. Studies by Hal Draper and others have thrown into doubt the idea that Marx saw revolution proceeding through the rule of the proletariat over itself; rather, it may be that Marx thought the state offices to be seized were simply a tool through which people could feed, house, arm, provide useful things, and defend themselves against armed attacks by the remaining anticommunist forces. His interest in the delegative, democratic structure of the Commune, which he calls the “political form at last discovered under which to work out the emancipation of labor” indicates that he and Lenin differ on this point. In a passage that hearkens back to his 1840s writing on the state, and his insistence that division between civil society and state must be overcome, Marx describes the revolution as functioning through “the reabsorption of the state power by society as its own living forces instead of as forces controlling and subduing it, by the popular masses themselves, forming their own force instead of the organized force of their oppression…” Karl Marx, “First Draft of The Civil War in France,” in The First International and After: Political Writings, ed. David Fernbach, Reprint edition (London: Verso, 2010), 250. The Commune’s “greatest measure” was “itself,” he writes, the fact that “people have taken the actual management of the revolution into their own hands and found, at the same time, in the case of success, the means to hold it in the hands of the people themselves” (263). We are less interested, though, in making an argument about what Marx really thought than in evaluating these ideas, on their own terms, which is why we confine this digression to a note. We are well aware that one can marshal all sorts of textual support for Lenin’s view on this matter. And even the best possible reconstruction of Marx’s thought on this matter strikes us as inadequate, from the present vantage. See Hal Draper, Dictatorship of Proletariat (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1987); a more recent and helpful survey can be found in David Adam, “Karl Marx and the State.” |

| ↑5 | Some may choose to describe this fraction as a “party.” We have no problem with this usage, except inasmuch as it might be confused with other uses of the term party. The dedicated fraction we describe is a more-or-less spontaneous product of unfolding revolution; it doesn’t precede the historical moment of an unfolding revolutionary sequence. It is simply the organized unfolding of the revolution, and the form that this organization takes, as people attempt to do what needs doing. This has no resemblance to the sort of party that is organized in advance of a revolutionary event and attempts to slowly accrue members so as to be able to act decisively in some future moment. Structurally, such parties are almost always bound to become opportunistic, counter-revolutionary forces. They are only useful inasmuch as they form the object for a split at the decisive moment – as happened with splits from and within the 2nd international during the revolutionary wave after WWI. For an example of this sense of party and partisanization, see “Spontaneity, Mediation, Rupture,” Endnotes 3 (2013), 240. |

| ↑6 | We cannot retrace this argument here, but see Theorie Communiste, “The Present Moment,” Sic 1 (2011), Jasper Bernes, “Logistics, Counterlogistics, and the Communist Prospect,” Endnotes 3 (2013), and “Spontaneity, Mediation, Rupture,” op. cit. We note, in passing, that Marxism broke with all previous forms of communism and socialism by abandoning a moral and idealist account of how communism would come into the world. Marx’s innovation was that communism would be the unfolding of self-interest. In other words, we can’t rely upon any conception of what people should do, nor even upon the superior, putatively scientific power of doctrine in the hands of dedicated militants. Communism will stand or fall based upon whether it is in the self-interest of the millions upon millions of people to fight for it and to institute and strengthen communist relations. Communism wins by being the most obvious, practical and appealing alternative on offer, within a particular revolutionary conjuncture. This superiority must be clear, sooner rather than later, to the greatest number of people, and not just a dedicated minority who act as guardians of a better future to come. This is why we believe communist measures will not only be the most obvious choice (perhaps the only choice) available to people, once other alternatives are exhausted, but the most appealing. If there is a task for dedicated insurgents it is in generalizing such measures and helping their success. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine