Before taking up the subject, it is necessary to point out that Socialisme ou Barbarie, primarily at the impetus of Castoriadis (alias Chaulieu), went through different periods, largely corresponding to political analyses of the prospects of struggle which conditioned the development of the group.

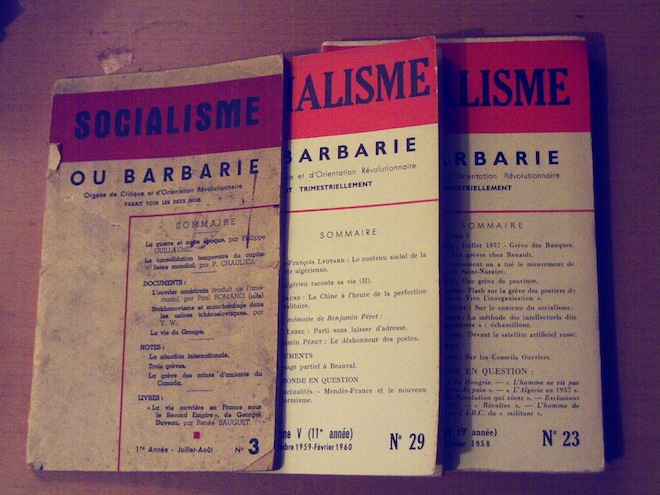

If one can schematically distinguish a Marxist period from a non-Marxist period, with the new positions of Castoriadis and the split of Pouvoir Ouvrier (Marxist tendency) in 1963, the preceding period, beginning in 1949, went through different approaches in the analysis of the economic, social, and political situation not only in France, but also in the entire world. In these different orientations, which are easy to detect in the 40 issues of the review, the question of workers’ inquiry was only posed in periods during which the group affirmed the primacy of the class struggle. It might be worth recalling that the Chaulieu-Montal tendency’s break with the Parti Communiste Internationaliste and the Fourth International happened over the question of the nature of the USSR; and at the same time, and for several years, the group essentially fixed its attention on the coming of the Third World War. But it could show an interest in the working class in the form of testimonies, as is demonstrated by the publication, from the first issue of the review, of a translation of Paul Romano’s text – The American Worker – and some reports on strikes in both France and abroad. But, then, it was never a question of workers’ inquiry and one cannot say that the class struggle and an attempt to understand the world of the worker were at that time primary concerns of the group.

Personally, I participated in Socialisme ou Barbarie from 1952 to 1958. I left Socialisme ou Barbarie with Claude Lefort (Montal) after an attempt by the majority of the group to create a political party during the events bound up with the war in Algeria and the Gaullist semi-coup. This rupture happened over purely organization considerations that did not directly put into question the interest in the action of the working class. On the contrary, the majority saw in Gaullism a kind of fascism (which was an incorrect analysis), and drew the conclusion that we were going to participate in a workers’ revolt, hence the necessity of a structured organization. This orientation was, however, in opposition to the concept of workers’ inquiry because the group saw itself, at that time, as a guide, a coordinator, a recruiter aiming to impose a line rather than drawing this line from an analysis of workers’ behavior. I would not know what to say about what really happened after 1958 – because I was no longer a part of it – except to comment on the texts published by the review, or to trust what my contacts in the group could tell me.

If the first issues of the review did not have an essential interest in having a deep understanding of the working class, of the proletariat in general and in particular, the 11th issue of the review, from November-December 1952, did address the question of workers’ inquiry in a leading article (not signed, which leads one to suppose that there was a consensus on this point, or a compromise) entitled “Proletarian Experience.” But, if this article spoke about inquiry, it was not to privilege this method of understanding what the proletariat really is, but, on the contrary, to rule in favor of these “narrative accounts.” It is interesting to copy this passage, which is the conclusion of a long text on theoretical developments:

Socialisme ou Barbarie would like to solicit testimonies from workers and publish them at the same time as it accords an important place to all forms of analysis concerning proletarian experience. In this issue the reader will find the beginning of such a testimony, one that leaves aside several of the points we have outlined. 1 Other such texts could broach these points in ways that go beyond those envisioned in this issue. In fact, it is impossible to impose an exact framework. If we have seemed to do so in the course of our explanations, and if we have produced nothing but a questionnaire, then this work would not be valuable: a question imposed from the outside might be an irritant for the subject being questioned, shaping an artificial response or, in any case, imprinting upon it a character that it would not otherwise have had. Our research directions would be brought to bear even on narratives that we provoke: we must be attentive to all forms of expression that might advance concrete analysis. As for the rest, the problem is not the form taken by a document, but its interpretation. Who will work out the relationships understood as significant between such and such responses? Who will reveal from beneath the explicit content of a document the intentions and attitudes that inspired it, and juxtapose the testimonies? The comrades of Socialisme ou Barbarie? But would this not run counter to their intentions, given that they propose a kind of research that would enable workers to reflect upon their experience? This problem cannot be resolved artificially, particularly not at this first step in the work. In any case, the interpretation, from wherever it comes, will remain contemporary with the text being interpreted. It can only impress if it is judged to be accurate by the reader, someone who is able to find another meaning in the materials we submit to him. We hope it will be possible to connect the authors with texts in a collective critique of the documents. For the moment, our goal is to gather these materials: in this, we count on the active support of those sympathetic with this journal.

All of this talk ends in this decision to put aside workers’ inquiry in favor of the first-hand narrative of a single person, when one knows what Socialisme ou Barbarie really was at that time: a core of some dozen militants with a few contacts in the provinces and review that circulated barely more than 200 copies. It was out of the question, for purely practical reasons to start any kind of “workers’ inquiry,” even less because only three or four of these participants were proletarians. Did this critical rejection not express the concrete impossibility of realizing this work, given the size of the group? Or rather, was it not the consequence of a political approach to the question – that the group had nothing to learn from the working class but, on the contrary, had several things to teach it? (This connects to the positions on the role of the organization that exploded in 1958 in the political turmoil of the war in Algeria.) In fact, the review would only include, following The American Worker by Paul Romano mentioned above, narratives from the proletarian members of the group. There is clear evidence that these narratives were influenced by the political vision of the group; this was particularly true, for example, with the Mothé’s narratives on the Renault Billancourt factory, which were strongly influenced by the Castoriadis’ positions.

The publication of this text on “Proletarian Experience” coincided with the development of struggle in France, notably the large strikes in 1953 and 1955, up until 1958, when the political problems tied to the war in Algeria gained the upper hand over the life of the group, the discussions in the group, and the articles in the review, privileged the workers’ struggles and the narratives in question, but at no moment did the question of “workers’ inquiry” posed in 1952 reappear. On the contrary, innumerable debates unfolded in the weekly meetings on the question of a workers paper. Such a paper existed, clandestinely, Tribune Ouvrière, operated by group of workers at the Renault factory in Billancourt (a suburb of Paris), a few of whom were close to Socialisme ou Barbarie (one was a member).

To recount the history of Tribune Ouvrière, workers bulletin of the Renault factory at Billancourt necessitates retracing the situation in the factory and the relations of labor in the fifteen years that followed the Second World War. To broadly summarize, this factory of about 30,000 workers, the “workers’ fortress,” as we used it call it at the time, was then dominated by the CGT, tied closely to the Communist Party, and which until 1947, imposed the management’s production imperatives. It was in line with the national political union for the economic reconstruction of capitalism in France.

The class struggle continued nonetheless, and Trotskyist militants succeeded in polarizing opposition against this politics of class collaboration in certain workshops in the factory, and in unleashing in April-May 1947 a wildcat strike and the creation of a strike committee outside the union. The violent repression of the strike ended with a compromise (signed by the CGT without the presence of the strike committee), but had political consequences: the ejection of the Communist ministers from the government (other factors also contributed to this ejection: on the one hand, the beginning of the cold war and alignment on the politics of the USSR, and on the other hand, the first war in Vietnam). The end of the strike saw the exclusion of the CGT from those sections that had launched the strike, which had to create a new union, the Renault Democratic Union (SDR), led by a Trotskyist militant, Bois. The existence of this union was very ephemeral because it clashed with both the CGT and the management (the legal arrangement practically prohibited it from participating in any discussion in the factory).

A few years later, in 1954, some participated in the creation of a new opposition in the factory, which regrouped, under the impetus of a militant close to Socialisme ou Barbarie, Raymond (who still refused to participate in the group), and other militants in the factory, an anarchist, Pierrot, the Trotskyist Bois, and a member of Socialisme ou Barbarie, Mothé. It was in this way that the workers bulletin, Tribune Ouvrière, was launched. It was totally clandestine and disseminated secretly in the factory - the CGT’s presence was still so strong that it could oppose any attempt to organize outside its union control. The true facilitator of this nucleus was Gaspard, who did not content himself with ensuring the appearance and distribution of the bulletin, but was a true organizer of a real nucleus of nearly 50 workers in a collective approach that expanded beyond the union into a kind of collective life outside the factory (vacations, cultural trips, etc.). I can testify to this since, organizer of an opposition core at my company. I occasionally took part in these “activities.”

There were attempts to turn Tribune Ouvrière into the worker bulletin of Socialisme ou Barbarie; these discussions aimed to define the method of such a bulletin, which was intended to propagate the ideas of the group, rather than to promote a deeper understanding of the proletariat. After 1958, and the group’s split, such a paper appeared under the title Pouvoir Ouvrier. No longer a member of Socialisme ou Barbarie after this date, I can only refer to publications in order to maintain that the question of Workers’ Inquiry was never addressed in the group, and even more so that even the worker narratives disappeared [from the review] completely, the group being in large part composed of intellectuals and students, and no proletarians.

The debates that, in 1958, led to Socialisme ou Barbarie’s split, were polarized around two texts on the role of the organization, one coming from Castoriadis, the other from Lefort. In this latter text one finds a brief reference to workers inquiry in the conclusion on “militant activity” in these terms: “On the other hand, one can begin several serious analyses concerning the functioning of our own society (on the relations of production, the French bureaucracy, or the union bureaucracy). One would in this way establish a collaboration with factory militants in a way that poses in concrete terms (through inquiries into their life and work experiences) the problem of workers’ management.” 2 But even there this remained a purely theoretical position without the possibility of practical realization given the reduced size of the group and, in fact, everything would unfold differently.

In a certain way, one can say that this approach to understanding the proletarian milieu was adopted by those who emerged, after the various turmoils that lasted up until 1962, as the minority that was more or less excluded from Socialisme ou Barbarie in 1958. It would take too long to explain how, from the autumn of 1958, we constituted an “inter-firm group” composed solely of proletarians, and which began to publish a monthly bulletin essentially reproducing what the participants could say about whatever happened in their factory. This bulletin ended up calling itself Informations Correspondance Ouvrières (ICO) 3 and continued under this form until 1968 where, once again, an influx of students fundamentally modified the original character of the group and the content of the bulletin. In a certain way this resembles workers’ inquiry, but it was in no way a response to precise questionnaire, but a narrative, eventually clarified by questions to other proletarians participating in the meeting. I must add that until 1967-1968, when economic and social development sparked a revival of interest in this experience, the membership of ICO never surpassed more than 30, the bulletin’s circulation having finally attained 1000 copies, and that the influence of the group remained negligible all the same.

Tribune Ouvrière disappeared around 1962-63 because Raymond left – and he took with him a certain number of Renault workers – to create a collective vacation center. In the years before 1958 discussions went on in Socialisme ou Barbarie about a “workers’ paper” that would express the group’s position on workers’ struggles to the workers. For some time some in Socialisme ou Barbarie had thought that Tribune Ouvrière would be this workers’ paper expressing the group. But the opposition of Raymond and the other members (except Mothé, who pushed for such an integration), nullified all these efforts. It was then that the majority, taking advantage of the 1958 split, launched the workers’ paper of the group: Pouvoir Ouvrier. It was neither the continuation of Tribune Ouvrière, which continued for some time in its original form, nor some formula that corresponded to it, but the paper of a political group carrying, in more accessible language, the good word to the workers: it did not base itself on any concrete workers experience. This was so true that at the time of Socialisme ou Barbarie’s new split in 1963, “Pouvoir Ouvrier” became the name and the political organ of the new group. After 1958 Mothé founded the paper according to the formula he defended in the review, but he quickly abandoned it to pursue a union career in the CFDT.

With Mothé having become a syndicalist, Raymond leaving for a commercial career, and Bois, who was the animating spirit behind Voix Ouvrières, launching factory bulletins that were closely controlled by the Trotskyist apparatus, Tribune Ouvrière could disappear because the majority of those who had directed it were working elsewhere. Only one of them was left, Pierrot, still a worker at Renault Billancourt, who joined ICO and became one of its animateurs. But one cannot say there was any filiation with Tribune Ouvrière, which disappeared practically the moment when ICO emerged on completely different bases than any of the groups of bulletins cited. Practically, all the participants in ICO were workers who, opposed to unions, shared their experience as workers, and their experience of the difficult struggle between the boss’s exploitation and the union bureaucracy; this made for an original conception, very different from both Tribune Ouvrière, limited to a single factory, and Pouvoir Ouvrier, the expression of a political group. ICO continued in this form practically until 1968, then everything was overturned in May 68 with an influx of non-workers, and with this influx a mutation towards a political group, which, for its part, led to shattering of the group around ideological orientations. Neither one nor the other of these so-called “workers’” bulletins can serve as models for today because they corresponded to certain structures of capital, to ensuing relations of production, and a certain union presence. A half century later, many things have changed in this area and few today discuss the “workers’ paper.”

ICO disappeared after 1968 in large part because of profound divergences over the role of the proletariat, some foreseeing a rise in struggles, which would justify a revolutionary perspective (which led to the reemergence of the old debates on the role of organizations and an irreducible cleavage between the Marxist and anarchist currents); others thinking the role of the proletariat was no longer central to the prospects of a communist transformation of society. These are the currents that still confront each other 40 years later, but the least that can be said is that neither one concerned itself with really knowing how proletarians live and struggle, and their vision of a non-capitalist world. For these currents – even though a whole arsenal of sociologists and ethnologists around the world try to tap into this in order to further the domination of the worker however they can, with the sole interest of ensuring the permanence of the system that exploits labor-power – the theme of workers’ inquiry is no longer relevant: for some it is totally useless, because the workers are no longer a determining factor; for others, as in the past, it is a secondary thing, because they still think they have to teach something to workers, and not the other way around.

—Translated by Asad Haider and Salar Mohandesi

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine