Issue 6: Imperialism

Strategies and Solidarities • Theoretical Encounters • Conceptualizing Imperialism Today • Articulation and Modes of Production • Imperialism and the Comintern • Black Internationalism

Strategies and Solidarities • Theoretical Encounters • Conceptualizing Imperialism Today • Articulation and Modes of Production • Imperialism and the Comintern • Black Internationalism

If imperialism today is irreducible to any single phenomenon, then this is because it appears at once both ubiquitous and dispersed. How then to account today for the history that has amplified imperialism while making it all the more difficult to define?

What I focus on is how queer radicals didn’t just work to win acceptance, but actually changed the meanings of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist struggle to incorporate sexual liberation – precisely because capitalism and colonialism depend on rigid sexual regulation.

The point is not to debate whether or not Libya was a socialist state. Much more interesting is understanding what were its strengths and what were its weaknesses.

At the same time that J. A. Hobson was writing Imperialism: A Study (1902), Liang Qichao, a major turn-of-the-century Chinese intellectual and journalist, wrote a magisterial essay on what he called “the new rules for destroying countries” [mieguo xinfa]. As Liang makes clear, conceptualizing modern Chinese history as dialectically part of modern global history not only helps generate new questions of and in theories of imperialism and modernity, it also helps generate new questions about Chinese history and the history of global revolutions.

The U.S. military in post-WWII Okinawa was not only interested in expropriating public and private lands in order to transform Okinawa into its keystone of the Pacific. It was also interested in allowing base enclosures to perform the constant ideological work of normalizing capitalist social relations in the islands. In other words, there was an articulation that complicates our understanding of how imperialist power operates; an articulation between military force and the restructuring of social life on a broad scale, namely through the redrawing of property relations.

A hypothetical “Algerian history of French philosophy” elicits a variegated but in many ways opaque picture. Arguably, it is only the generation that came of political age in the late 1950s and early 1960s – the generation of Balibar and Rancière – that, with considerable delay, incorporated the questions raised by the decolonization of France and Algeria into their thinking, but when they did so it was not in terms of the problematic of revolutionary anti-colonial violence, but in terms of the antinomies of citizenship.

The LAI’s theoretical organ The Anti-Imperialist Review and its editorial history represent a constituent source of militant reportage on global anti-imperialism between the two World Wars, as well as a rigorous effort to construct a conceptual framework within which the international communist movement could politically analyze how these phenomena were articulated within the broader international relations of force. The dead-ends and contradictory ideological and political shifts that the LAI had to navigate also point to the insurmountable problems of the anti-imperialist practice of Comintern-linked organizations.

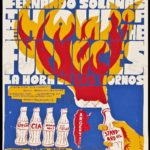

The state of bankruptcy under imperial rule interrogated by Hora de los hornos allows us to consider what Randy Martin diagnosed as the “financialization of daily life” together with what the Situationists called the “colonization of everyday life” within capitalism, while surpassing each of these theses by insisting that quotidian violence is inseparable from imperialism as a historical and cultural process.

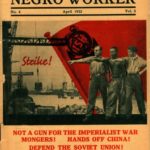

The Negro Worker surveyed the geographies of colonialism and imperialism through the labor regimes which marked the uneven development of global capitalism, and in doing so also plotted the different trajectories and strategies of anti-colonial struggles.