In July 2016, a number of Saudi women’s rights activists launched a campaign advocating for the end of the male guardianship system. This system describes a set of laws in Saudi Arabia that position women as life-long minors, with all their life choices determined by a male relative, who could be their father, husband, brother, uncle, or even son. This was not the first time such a call, or indeed a campaign, was made, but this time it was different.

It was launched in coordination with the launch of Human Rights Watch’s report, Boxed In: Women and Saudi Arabia’s Male Guardianship System, under the slogan Together We Stand to End Male Guardianship of Women (#معًا_لإنهاء_ولاية_الرجل_على_المرأة). What that call would quickly unleash was something no one anticipated: Saudi Arabia’s first feminist mass movement.

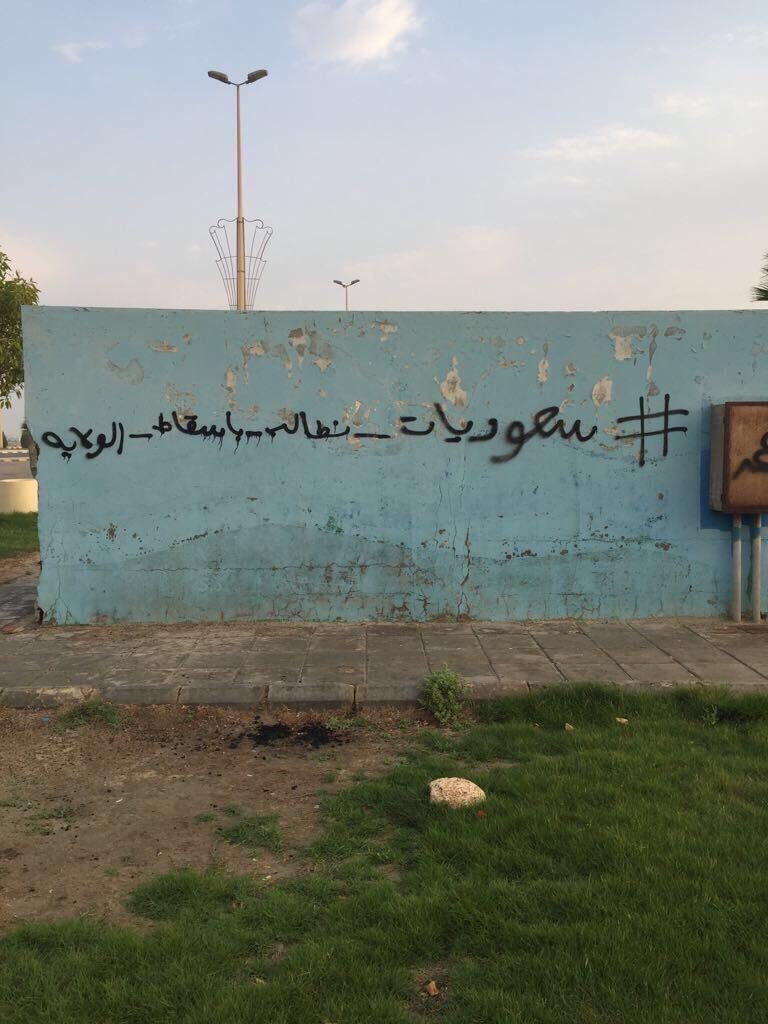

The movement, which quickly swept the country, pushed aside the slogan the activists had chosen for their campaign for a much more radical slogan, Saudi Women Demand the Overthrow of Guardianship (#سعوديات_نطالب_بإسقاط_الولاية). To maintain its momentum and keep it trending on Twitter, the hashtag would be followed by the number of days since the new movement started. As of writing this article, it has been 1,085 days.

For two years, the movement seemed like it could only gain momentum. In a mass collective process of consciousness-raising to develop a fully articulated understanding of women’s varying social positions, the movement seemed like it could only grow more radical. Thousands of women would speak out – sometimes publicly, but more often anonymously – about their personal struggles within their families, communities, and with the legal system.

Attempts at detaining prominent women activists, including one of the authors of this piece, for publicly challenging legal and social dress codes, among other issues, were met with massive social media-based solidarity campaigns that led to their release.

However, the movement’s first major victory was preceded by its first major setback. On May 15, 2018, nearly one month before the infamous driving ban on women was to be lifted, the movement’s most prominent activists were rounded up and detained by the newly-founded Presidency of State Security. In the following months, several more activists were arrested, and even more were put under travel bans.

After this brief introduction to the ongoing feminist struggle in Saudi Arabia, we would like to take a step back. We do so in order to place this struggle in its appropriate historical and social framework. This is necessary because of how easy it is to fall into the casual racist and Orientalist depictions of women and their movements, in the Global South in general, and in Saudi Arabia in particular.

First, we will attempt to place the question of women’s oppression in Saudi Arabia in its proper historical framework. Second, we will offer a brief account of how the conditions of women came to be what they were before the new movement started. Lastly, we will provide a history of how the ongoing movement started.

1. Historicizing the Question

Historicizing the question of women’s oppression in Saudi Arabia requires critiquing and doing away with two approaches: dismissive universality and cultural reductionism, the former being an insufficient, inappropriate, and – to many women in Saudi Arabia – insulting response to the latter.

While cultural reductionism is a decisively anti-feminist position, dismissive universality can be – or is – an impediment to international solidarity.

Dismissive Universality

Arguments we consider as falling into dismissive universality go as follows: While it is true that women in Saudi Arabia do face oppression, women are oppressed everywhere! Actually, in some aspects, Saudi women have it better! Think of paid maternity leave!

These “better” laws do not hang in the air, but rather exist within a whole set of sexist and anti-labor rights laws and social structures. Hence while women do have maternity leave, a woman could be easily fired if she actually gets pregnant. This particular legislation was not put in place as a result of feminist struggles, but at the request of conservative Islamists who feared women’s work would prevent them from doing their motherly duties: it was enacted so that women’s work would not disrupt established patriarchal relations.

The fact that women’s oppression is universal is a well-intentioned shorthand response to the Right pointing out the severity of women’s oppression in Saudi Arabia. A proper response to the reactionary exploitation of these realities for misogynistic and racist purposes, however, cannot have, as its basis, the dismissal of those realities and their significance.

The problem with these arguments, indeed, is not in their misunderstanding of this or that particular law or social relation, but in their dismissal of national particularities, i.e. of the fact that women could be said to have it worse in one country more than another. Generally, women in Saudi Arabia do in fact live under much more severely oppressive conditions than women in the United States. Feminists in Saudi Arabia are quite aware of that.

These arguments also end up dismissing the voices of women in Saudi Arabia, some of whom have lived abroad, when they say, “yes, our living conditions are overall much worse than the living conditions of women in the West where these arguments are made. We know that for certain, because we have lived both under your conditions and ours.” There is definitely a great sea of difference between conditions in countries that have experienced several women’s liberation movements and one that has not.

Cultural Reductionism

The Western Right speaks a lot – to the point of obsession – about the conditions of Muslim women. (Italicized Muslim will be used to signify a racial, rather than a strictly religious, category.) Because of Saudi Arabia’s centrality to Islamophobic racial ideology, Saudi women occupy the centerpiece in this ostensibly pro-women discourse.

But something here must be clarified. The Right has never made the argument for Muslim women’s liberation in the “East” – nor ever will. The Right is, simply put, making the argument for Western imperialism in the “East,” and, importantly, for the rolling back of the achievements of the women’s liberation movement in the West. Imperialism, especially in its overt military form, is inseparable from a domestic assault on working-class and emancipatory movements.

To clarify what we mean by stating that cultural reductionism is a universal assault on women’s agency, self-determination, and autonomy, we will elaborate and analyze the Right’s narrative on the position of women in Muslim societies, and its implications for women in the “West.”

Two notes before we begin. First, while our analysis is about narratives, it must be clear that we understand that this is simply the discursive expression of a political project, and it is that project that needs to be confronted, not just this one expression. Second, for simplicity’s sake, we will casually use the term “West” without problematization, since that is beyond the scope of this article.

The logic of cultural reductionism goes as follows: Muslim women are uniquely oppressed women.1 Their oppression is caused by their society’s uniquely anti-women culture, i.e. Muslim culture. This culture is the polar opposite of Western civilization, which, obviously, allowed Western women to progress and advance to the point of parity with men. Western women’s oppression (if it exists), is either negligible or is caused by a few, degenerated uncivilized submen individuals. In other words, it is not systemic, but interpersonal and racial; resulting from the animalistic predatory Black men and genetically degenerated poor whites. In order to prevent these interpersonal transgressions from these degenerated/uncivilized submen individuals, there should be a more robust patriarchal involvement in the national community to protect Western/white women.

It is not just Muslim women who are passive subjects in this narrative, but all women and all racialized people. Their social position is determined by the civilization, i.e. men, they belong to. That these men have allowed their women to reach the position they have means that these men, too, should determine when and where these women have gone too far.

This reveals the consistency between the Right’s staunch misogyny towards “their” women and the alleged advocacy for the liberation of racialized women. The line that connects them is the intended denial of women’s historical agency. In attributing the achievements of the women’s liberation movement – and, similarly, the Black and Queer liberation movement(s) – to Western/white civilization, they erase the long history of struggles carried out by these peoples themselves for their own self-emancipation. The intended effect is the reinforcement of racist, patriarchal, and, therefore, capitalist social relations.

It can accomplish all that because it does not simply deny women their historic agency. This patriarchal domination is established through a war on an essentialized subman subject, who is not just non-white, but also working class.

Fighting against this cultural reductionism means recognizing the historicity of women’s position not just in the Global South, but also in the Global North. That is to say, the current position of women in every society and community is the contingent result of emancipatory political struggles. We say contingent because it is neither predestined, unchangeable, nor emancipatory in a linear way. 2

2. How We Got Here

In this section, we provide a historical account of how things came to be, starting with the early processes of state formation, through the influence of Islamism, and ending at the way things were before the so-called New Era of King Salman.

Date Palms, Oil Rigs, Gender and Color Lines

Elderly Saudi women’s narratives of “pre-oil” Saudi Arabia are inseparable from their narratives of “pre-Islamist” Saudi Arabia. To some, this is a story of disempowerment and repression; to others, it is one of religious enlightenment and social mobility. Between these two poles a multitude of narratives exists, depending on which specific transformations affected each woman in her respective community, and their specific attitudes towards them.

Gender relations in pre-oil Saudi communities varied significantly. There were urban, rural agricultural, feudal, (iḳṭaʿai) sedentary, tribal, and non-tribal communities under different forms of rule. This variety in social formations meant a variety in gender relations as well. What they all had in common, however, was laboring class women’s involvement in non-domestic labor.

Besides teaching, medicine, small trades, and crafts, women also took part in farming. They did not do so, however, on a basis of parity. Women were limited to specific tasks in date palm farming, for example: “The man was on top of the date palm, the woman below,” picking from the ground whatever falls from atop, as one woman described it.3 In other words, not only were women restricted from specific fields of labor, they were even limited to specific tasks in those they partook in.

Major transformations started in the 1930s and 40s with the advent of oil production under direct American corporate management, which was central to the Saudi state-building project. After decades of intensifying date commodity production for export to Western markets, the deteriorating conditions of the peasantry in nearby oases in eastern Saudi Arabia provided an abundant supply of cheap labor for American oil corporations. In this American-managed oil labor market and the expanding Saudi state bureaucracy, women were completely excluded.

But the Americans’ imposition of Jim Crow practices, the color line, and hyper-exploitation of what they referred to as “native” labor, sparked decades-long labor struggles, led by Arab nationalists and communists.

These labor struggles advocated, among other things, for the nationalization of the oil industry; the abolition of slavery, ending segregationist practices; women’s education; and instituting labor and political rights, including calls for drafting a constitution and introducing an elected parliament with full legislative powers. While some of those efforts were successful, others not so much. The color line was eventually (at least nominally) abolished, but the newly-introduced gender lines remained in place despite some challenges from the labor movement.

Throughout the following decades, as wages increased as a result of antiracist struggles and increasing oil prices, imported commodities sidelined local crafts and trades, and agricultural work became less fruitful, women were practically ejected from virtually all spheres of non-domestic labor. A single-breadwinner household was largely instituted.

With the institution of girls’ education, the black ‘abaya was instituted as the nation-wide, state-enforced dress code for women. For the longest time and in most of what became Saudi communities, the black ‘abaya used to be largely the dress of upper-class women, who, unlike toiling women, lived mostly in seclusion.

Then Came Juhayman

In Mahmoud Sabbagh’s 2016 drama-comedy film Barakah Meets Barakah, the male protagonist, Barakah is prevented from entering a “families-only” area where he was supposed to meet the female protagonist, also named Barakah. He returns home, where he sees his silent, unresponsive sickly old man, and asks a question meant for the audience, “What happened to us, old man?”

The question turns to a monologue; a series of photographs and video clips are shown, comparing “how things were” (liberal/normal) and “how they became” (Oriental/grotesque). Barakah concludes, “Your generation lived life to the fullest, then got scared once you aged.”

Portrayals of Muslim countries’ “pre-Islamist” past through photographs of (a few) women’s dress – where women’s bodies are made to advance reductive narratives about “how things were,” or more precisely, how they ought to be – are not unique to Saudi Arabia. They are most commonly used in reference to Afghanistan and Iran. The narrative usually goes as follows: women’s rights experienced a steady progress throughout the 20th century until the 1970s, and were then rolled back. Changes in legal codes are assumed to reflect immediate change in gender relations, while women and their everyday experiences take the backseat.

In Saudi liberal narrative, the story of Juhayman serves as the critical moment after which gender relations went through radical transformation. On the first day of the 15th Hijri century, which corresponds to November 20, 1979, Juhayman al-Otaybi stormed and seized the Great Mosque of Mecca with a few hundred armed followers, with the intent of consecrating a man named Muhammad al-Qahtani as the Awaited Mahdi.

The Juhayman incident is seen as that boogeyman the previous generation – and the Saudi state – feared. It is a shorthand for the period of Islamic Awakening (Saḥwa), which began in the 1970s and witnessed the rise of several Islamist tendencies across the country and the region. Juhayman was arrested and executed after the Grand Mosque was raided by security forces. In Saudi liberal narrative, Juhayman may have died, but he lives through all of our social relations.

The Saḥwa was, in fact, a state-sponsored project specifically meant as a counter-weight to the influence of Arab nationalism and Nasserism (and their anti-monarchist tendencies), through supporting Islamist tendencies. These Islamist tendencies had “modernizing” Islam as a central mission – the idea was to update Islam in response to a concept defined in opposition to it. This meant a never-ending quest to respond to every innovative social concept, idea, and project. Throughout the 20th century, it meant a response to “secular” conceptions of national liberation.4

Arab nationalism’s specific view of women’s social position in the post-independence nation-states in the image of the Modern Arab Woman provoked a response in the image of a Modern Muslim Woman. The former is removed from her backwards traditional past through unveiling, but maintains her modest dress and, therefore, the chastity of the nation. The latter maintains that tradition through veiling, while proving its compatibility with modernity through excelling in the sciences and the noble arts.

Needless to say, despite Saudi liberal assertions to the contrary, the Saḥwa did not run in complete contradiction with existing gender relations, nor does it have full-explanatory power over their transformation.

There should also not be a denial of the fact that current restrictions on women’s right to self-determination and autonomy are partly based in – but not reducible to – specific interpretations of Islamic jurisprudence and scripture, in their capacity as one of the bases for the Saudi state legal ideological apparatuses.

This is not to say that religious scripture written in the 7th century can without mediation (in the form of reinterpretation) form a basis for ideological state apparatuses. Rather, religious interpretations were reshaped by transformations in social relations, and would in turn reshape these social relations, most significantly through conflicts within the emerging postcolonial nation-states.5

It is, therefore, not just a mistake to describe these conditions as “medieval” as is often done; the severity of these oppressive relations, which will be described below, is a strictly modern capitalist condition. The nation-wide elaborate policing and regulation of millions of women’s lives and the severe restriction of their autonomy would have been unimaginable under any previous mode of production.

Before the New Era

Legally, the policing and regulation of women’s lives begin very early on: girls and women in all stages of education (elementary, intermediate, secondary, and universities) are not allowed to leave their school campus before the arrival of their pre-approved male guardian to pick them up. Girls have to wait inside the campus, as the school custodian, a man, calls the names of their fathers through a megaphone in order of arrival.

The practical reality of this order is not just everyday inconvenience; it can be literally murderous. The most infamous case being the 2002 fire in a girl’s school in Mecca, where twelve girls died when the religious police did not allow them to leave the school uncovered. The latest known case happened on July 2 of this year, when a college girl passed out in Ha’il, and first responders were not allowed to enter the scene because they were men; she died without receiving treatment.

Moreover, women are legally not allowed to go to university, get a job, live outside of their home, open a bank account, get an identification card, get a passport, travel abroad, or even leave prison without a written approval from their male guardian. “Undesirable” or “disobedient” women, and women who escape abuse and refuse to go back to live under their abuser or another guardian, have to live in indefinite detention under state custody in the so-called “Care House.”6

It gets worse: all medical operations relating to women’s reproductive organs, including cervical cancer treatment, have to be approved by a male guardian. Doctors speak of incidents where unexpected complications happen during labor, and the delivering mother needs a life-saving surgery, but the doctors cannot do it because they cannot get a hold of the husband.

This restriction, in its everyday effect, translates into the male guardians’ discretion over their women’s lives. This plays out differently for Saudi women across the Kingdom, as varying social norms, dominant political tendencies, different tribal affiliations (or lack thereof), along with urban and rural physical geography, set different limits on things like dress codes, labor market access, and mobility.

Whether strong community and extended family or tribal ties exist; the degree to which the nuclear family has been instituted; whether the family lives in a small highly accessible town or not; whether the father himself is one or another kind of Islamist or liberal – all play a role in setting the limits on just how repressive or how lenient a male guardian is or can be.

These limits, of course, are always in a process of individualized and collective struggles, from both the “guardian” and the “guarded,” with new arenas of struggle opening with broader social changes.

For example, with increasing costs of living since the 90s, the sole breadwinner household was gradually becoming an unviable position. This led to an increasing number of single and married women joining the labor market to support their household, first in education and medicine, then in management jobs, and later on as low-waged retail workers.

The simple fact of having an independent source of income was no direct source of liberation. For some, it was the basis for further restrictions and limitations. A father, for example, would let his daughter work, but seize her income and prevent her from ever getting married, so as not to lose this source of income. What this change in women’s relation to the labor market resulted in was no direct improvement, but opening the door for new struggles.

In both girls’ and boys’ schools, women’s domestic and subordinate social position is explicitly taught. Girls are given “house-keeping” classes throughout their twelve years of education, formerly called “womanhood” classes, and until very recently they had no physical education classes. Both boys and girls are taught in Islamic education classes that wife-beating, “within the boundaries of Islamic jurisprudence,” is a proper punishment for disobedience (including refusal to have sex) – this remained in place even after a law criminalizing domestic abuse was put in place in 2013, after years of feminist campaigning.

While the Male Guardianship system gives male guardians discretion in how they regulate their women’s lives, for migrant women who live in the country without a male relative, the kafala (sponsorship) system serves that role. The kafala system is a work-permit sponsorship system used in all Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, where all migrant workers “must have their entry and employment sponsored by a citizen.”7

In Saudi Arabia, the Kafala system, in its current form, came to prominence after state reform of the labor market following consecutive oil booms and a series of labor and political struggles.

Following the second oil boom of 1973-85, ruling families in the Gulf, as Omar AlShihabi puts it, wanted to “cement their ruling credentials” through modernization projects. However, “the sheer quantity of capital resulting from the enormous oil revenues, and the number of associated investment activities, exceeded the capacity and quality of the available domestic workforce.”8

The use of the local labor force was not a viable option, since it “went against the logic of the modernist welfare state that was supposed to pull local people out of the dire economic situation they found themselves in prior to the windfall from the oil revenues.”9 Nor was it importing Arab workers, who had historically played a vital role in labor and political struggles in the Gulf and were increasingly seen as potentially subversive elements. Importing non-Arab labor deprived of political and labor rights was the route the Gulf states took.

This route gradually led to a labor market where migrant workers occupy the large majority of low-waged private sector jobs, while Saudis work in the higher-waged expanding public sector jobs.

Under this system, the state grants citizens the ability to issue work permits, which gives the kafeel (sponsor) a great degree of control over their sponsored workers’ lives, due to the latter’s restricted residency and mobility rights. First put in place by British colonial authorities in the Gulf, the Kafala system enables egregious practices, such as confiscation of passports and work without pay for months, among others, which are so widespread as to be systemic.10 These practices are further exacerbated for migrant women, especially domestic workers, who came to be increasingly employed by the expanding Saudi middle class.

While most non-domestic migrant men and women have access to networks of solidarity (other migrant workers) and the sending-countries’ embassies to both alleviate and fight against these practices, domestic workers tend to be isolated within their sponsor’s household, where they live.

Migrant workers, in general, can be made to work extra hours without pay, but domestic workers’ workday has no limits; it begins and ends at the discretion of the employing family. Domestic workers’ tasks, regardless of what the contract says, are limitless. Again, in contrast to most migrant workers who can – and do – strike against months of unpaid work, migrant domestic workers cannot engage in resistance without risking further abuse.

Unlike Saudi women, who could in certain situations rely on extended family and community relations to alleviate their grievances, migrant women barely have any negotiating power to protect them from abuse. These severe conditions often have only the most drastic solutions. One is to flee the household – at times risking their lives to do so – and live without documents in a country that already has limited opportunities in the labor market for women. However, in too many cases, the only way out is to commit suicide.

To be clear, while all migrant working women are notionally subject to the same system, there is a very clear stratification in its concrete application. Upper-class migrant (mostly) American and European women – who work in higher education, medicine or the oil industry – tend to live in expat camps (i.e. gated communities) where even the laws that Saudi women have to live under do not apply.

In this new division of labor and reorganization of the labor market, new processes of racialization came into being. Their most severe impact is seen in the application of the death penalty. According to a Reprieve briefing, from start 2014 until mid-2017, 36% of all 438 death sentences passed were against foreign nationals, which rises to 40% if we set aside the 2016 mass execution of 47 men under Anti-Terrorism Law charges. In 2017 alone, 23% of those put to death for drug offenses were Pakistani nationals, who make up no more than 6% of the population.

Moreover, every few years, a woman or two are executed for witchcraft. While executions for witchcraft are rare, this charge is more often than not a racist trope: something to be watchful for in Asian and African domestic workers. Unlike Saudi women, the chastity of non-Saudi migrant women is not assumed nor is their sexuality regulated. Moreover, low-waged Asian and African migrant women are racially portrayed as both sexually undesirable and promiscuous, which is commonly used to justify sexual violence against them. A Saudi man, after all, would not be made to have sex with an Asian or African migrant, unless she engaged in witchcraft or “manipulation.”

Racist portrayals of the dangers of Asian and African migrant men as sexual predators to the chaste Saudi woman, on the other hand, were used both as a pretext to police their presence in the nation, justify their denial of economic or political rights, and push back against calls for gender equality.

If Saudi women were to drive or leave the house as they please, without a male guardian, who would protect them against sexual predators who could rape them or “manipulate” them into having sex? In the same breath, racism and misogyny are mutually reinforced, by proclaiming the subhuman status of all women and all racialized peoples – all to be policed by the Saudi man.

3. A New Movement Arises

In 2011, Saudi Arabia was one of the few countries that did not experience the nation-wide revolutionary movements that overtook the region. With the exception of Qatif, an eastern city with a long history of mass political activism, there were only a few small protests scattered around the Kingdom. The new regional political climate, however, not only raised the ceiling of demands higher but also forced the Saudi government to loosen its grip on freedom of expression.

The result was a flourishing of political debate around each and every issue. One could open an official newspaper and read op-eds making the case for a constitutional monarchy, for the necessity of political freedoms, for legalizing unions, and for gender equality. But what was on the pages of newspapers was only a small reflection of a bigger trend on non-state-controlled media.

There were YouTube comedy channels dedicated to criticizing public policies, corruption, and dealing with issues such as poverty and even state repression. People on social media, especially on Twitter, which most Saudis use, were even more daring; because of the number of political campaigns launched first on Twitter, it started to be called our “parliament.”

The October 26 Campaign

Women’s rights activists found in this an opportune moment to renew calls for ending the driving ban on women and the male guardianship.

The first challenge women activists launched took place on November 6, 1990, when 47 academic and professional-class women took their cars, usually driven by their chauffeurs, and drove around Riyadh until they were stopped and arrested. The women were publicly denounced on state television for their act of transgression, some lost their jobs and had their passports confiscated.

This did not stop women activists from continuing their work afterward, though mainly on the field of advocacy and consciousness-raising.

Throughout the ‘90s and the 2000s, a series of reforms were passed, including a further opening of the job market to women. The most radical demand at that time, however, was women’s right to drive in a country that had little to no public transportation and barely any usable sidewalks in cities designed solely with cars in mind.

In 2007, a couple of years after the crowning of King Abdullah who had previously expressed his support for women driving, the un-official Association for the Protection and Defense of Women’s Rights in Saudi Arabia, founded by Wajeha al-Huwaider, presented a petition.

The year after, al-Huwaider – a prolific writer and an activist who was arrested and intimidated in previous years for her activities – filmed herself while driving her car on International Women’s Day, as a protest against the ban. In 2011, another Saudi woman, Manal al-Sharif, would do the same.

Following her arrest and eventual release, Manal would later apply for a driver’s license and file a lawsuit against the General Department of Traffic upon her rejection. Another activist, Samar Badawi, would pursue a similar lawsuit, having pursued another lawsuit in the past against banning women from partaking in municipal council elections.

In 2013, a new campaign was launched to challenge this ban, to “stage a protest drive” on October 26. This followed a few publicized challenges to the ban. After the call was made for this protest drive, the October 26 campaign’s website was censored, and the women leading the campaign were contacted by the Ministry of Interior discouraging them from participating.

This intimidation did not stop them. Dozens of women filmed themselves driving in the streets of their cities, with a coordinated but individualized challenge to the ban.

Government statements contradicted one another. The Ministry of Interior stated that it would respond “firmly and with force” if the breaking the ban was repeated, which it was. At the same time, it stated that the ban, which they also state does not exist, would be lifted “once society is ready.”

In December 2014, Loujain al-Hathloul, a social media influencer, along with Maysaa al-Amoudi, challenged the claim that there is no ban, by live-tweeting while driving across the Emarati-Saudi border, using an Emarati driver’s license. If there was truly no ban, they would be allowed into the country; if not, they would be turned back. Neither happened. They were arrested at the border and put in prison.

In past cases, the activists would be taken into police custody and made to sign “pledges” to never do this again. This time, there was an unexpected escalation. Loujain and Maysaa were to be tried before the anti-terrorism Specialized Criminal Court. But again, following national and international outcry over the absurdity of this escalation, they were both released.

Women’s right to drive was only the most visible part of a much broader campaign, a central part of which was consciousness-raising about the systemic nature of women’s oppression.

Saudi Women Demand the Overthrow of Male Guardianship

When the campaign first launched, no one would have thought that it would turn into a mass movement.

What distinguished this campaign, or rather, what made it into a movement, is that previous campaigns were made up of relatively privileged women. Almost all of them either had enough money to have a car of their own, or had a male guardian who allowed them to use their car to challenge the law. This time, it was a movement mainly composed of women with little to no privileges, for some of whom, as a now-imprisoned feminist activist described, “their only room for autonomy from their families was an anonymous Twitter account.”

It was a movement where thousands of women talked online to each other about their personal struggles, and established local feminist circles and much broader networks of solidarity across the country. The movement was decentralized, yet not leaderless. Veteran women activists such as Azizah al-Yousef and Loujain al-Hathloul were, only partly due to their privileged position, able to direct at least the discourse of the movement.

However, this was a leadership based on the recognition that they were only doing so on behalf of non-privileged women. As Loujain herself put it, “I am a woman who has familial and class privileges, but I will not forget the suffering of girls who do not have the personal space that I do. It is my duty to use my privileges so that all women in my country would get their rights.” The movement also produced a new set of leadership, some with known identities, many more anonymous.

These circles and networks worked to establish consciousness-raising platforms, debating and educating on issues such as sexual health, a topic barely discussed in open terms; ongoing work against all forms of body shaming; child marriage (which is still legal in the country); toxic marital and extramarital relationships; domestic abuse; medical abuse, such as the excessively high rate of c-sections and the routinization of episiotomy without informed consent; racism, stateless Saudis, the abolishing of the kafala system as a central feminist demand; Palestine and why it matters to us as feminists; sexuality and varying gender expressions; an ongoing movement for translating feminist literature into Arabic – the list goes on and on.

Sooner than later, these circles and networks became a basis for mutual support. Saudis living abroad would send in contraceptives and abortion pills to the country, which are particularly inaccessible to unmarried women. The #MeToo moment immediately caught on, with exposures of sexual harassers in the workplace, on the streets, among public figures, and even men within the movement itself.

Several public space campaigns were launched that kept in mind the risk associated with visible public organization and therefore relied on discrete forms of protest. The #ResistanceByWalking campaign was a notable one, where women would take videos of themselves running everyday errands, to show the difficulty of doing so in high-temperature cities designed with cars as the only mode of transportation in mind.

Another one was the “inside-out” ʿAbaya campaign, which served (along with niqab and Abaya burning) as symbolic protests over the country’s dress code. Significantly, the “inside-out” Abaya campaign was also meant to break the movement out of social media and private meet-ups and into the “real-world”: women, for the first time, could easily identify fellow movement women in public spaces.

But activists were not the only ones to be taken by surprise. The state, which relied on the family as the apparatus to keep women in check, had no clue about how to deal with this movement.

The situation especially went out of hand when several girls – such as, Dina Ali, , Ashwaq and Areej al-Harbi, Shahad al-Mohaimeed, and Rahaf al-Qanun, among many others – attempted to escape the country, which was and still is perhaps the only viable, though quite dangerous, path to run away from an abusive family. The state, on behalf of the abusive families, attempted to return them home by voiding their passports and trying to extradite them, sometimes successfully.

Regardless, each case caused an international scandal, especially since the new young Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MBS) came to power with promises of social liberalization and economic neoliberalization – the latter of which set high hopes for international capital.

MBS did enact some reforms, but, as per tradition, they were not nearly close to what the movement was calling for: women would be allowed to drive, and guardian’s approval for work, school, and gynecological operations would no longer be needed, among other things. This long-awaited, limited victory was, however, a bitter one.

While we were all celebrating, the most prominent activists in the movement were all silent. It became clear that they had all received calls from State Security threatening them against any form of public celebration or commentary. Only the Crown Prince was to be credited for what they had long fought for.

We were fully aware of the limitations of these reforms. What they established was mainly furthering the limits of a guardian’s discretion. A woman could theoretically get a job, go to college, drive a car, apply for (but not receive) a passport, without his approval, but since in actuality she still has to live under his roof, that is not really the case.

To be clear, the reforms made a great deal of change, which cannot be understated, but only for somewhat financially-privileged women with already lenient guardians.11 Still, we were hopeful, since this opened up new arenas of struggle.

Surely, the political atmosphere was tense, or to be precise: the country was going through a historically unprecedented level of political repression in both scale and severity, especially after the new Crown Prince came to power. Several waves of mass political arrests and even mass executions occurred since 2015. The state was no longer content with silencing critics – a new process of istinṭāq (to force to speak) came into being: those who are not constantly and properly flattering the Crown Prince and his Vision 2030 risk persecution.

The Ministry of Interior launched an app called Kollona Amn (We’re all Police), a platform for user-generated mass-scale political repression and every day policing that is still available in app stores. To give a glimpse of their mission, their latest tweet at the time we wrote this article, reads: “Be the first policeman, and contribute in the defense of your homeland…by reporting holders and diffusers of deviant ideas on social media.”

Cracking down on the feminist movement was, however, no small task. At least since 2011, the state has been developing its capacity to surveil social media. Twitter was no small problem to regulate, especially in a situation where most users do not have any publicly identifying information.

In 2016, the Saudi government founded the Ideological Warfare Center under the Ministry of Defense. Its function, however, was fundamentally to capture social media through an electronic army of thousands of Twitter accounts ran by real people. The state not only came to have virtually absolute control over what goes trending, but launched a massive campaign of looking through people’s tweeting history, and arresting them on that basis.

In mid-2018, the worst-case scenario happened. Several of the most prominent activists in the movement were arrested: Loujain al-Hathloul, Azizah al-Yousef, Eman al-Nafjan, Ibrahim al-Modaymeegh, Mohammad al-Rabeah, and later on, Nouf Abdulaziz, Mayya al-Zahrani, Hatoon al-Fassi, Nassima al-Sadah, and Samar Badawi. Many more were summoned, interrogated, and put under travel bans.

What provoked the arrests seemed to have been a formal application submitted by several of them to establish a shelter for domestic abuse survivors, but that this was an attack on the movement as a whole is unquestionable.

Within days, state-controlled media outlets and its electronic army labeled them “traitors” and “agents of embassies.” For months they were held incommunicado, but after that Loujain’s sibling spoke up about what her sister went through and some news eventually leaked out about the others, we learned of the horrors they experienced. Most of them were subjected to all kinds of physical and psychological torture. Some, because of that, attempted suicide. The situation was dire.

State-media outlets were constantly attacking and attempting to discredit the movement, ludicrously equating feminists and women who escape domestic abuse to ISIS because “both harm the homeland,” the latter by mass murder, the former by damaging its reputation.

Having been dealt such a serious blow, with most of its prominent names either silenced or disappeared, it seemed as if the movement was on its way to die. Every once in a while, however, a new burst of activity would occur around a specific issue.

In March 2019, after months in which Saudi human rights activists in exile campaigned for their release, Azizah al-Yousef, Eman al-Nafjan, and Hatoon al-Fassi were temporarily released, still awaiting trial. Azizah’s son, Salah, shared a selfie of the two of them together, smiling, after her release.

The picture was widely circulated, and became a source of encouragement and new hope, but not for too long. Salah would be among around a dozen activists who would be arrested the following month. This time, they were mostly men, along with a couple of women who were involved in Saudi Arabia’s progressive intellectual production. Bader al-Ibrahim, Mohammad al-Sadiq, Thamar al-Marzouqi, Ali al-Saffar, Abdullah al-Duhailan, Redha al-Boori, Khadija al-Harbi, Fahad Abalkhail, Ayman Aldrees, Abdullah al-Shehri, Sheikah al-‘Irf, Mogbel al-Saggar, and Nayef al-Hindas.12

With regard to the reasons behind their arrests, we assumed that it was either their association with the feminist movement since men’s arrest tends to draw no international scrutiny, even with two of them being American citizens; or their longstanding pro-Palestinian cause advocacy, which offered national liberation as a definitively progressive alternative explanation to the Saudi state’s old and bankrupt religious Muslim-Jewish conflict narrative. Their advocacy is troublesome as the state pursues Trump’s Deal of the Century. Or, it could be both, as the two causes, in Saudi Arabia, more often than not intersected.13

Some recently “empowered” women, including members of the Shura Council, the Kingdom’s powerless legislative body, led the electronic army in a vicious campaign against feminism and feminists. The basis for their attacks changed periodically: they were throwing everything at us to see if something sticks. At first, using old misogynistic tropes, they called feminism a movement for mentally ill women, adding that there is a difference between women’s rights and feminism, the latter being about hating men. Some stated that women who think they are discriminated against simply have “weak personalities” and should only blame themselves.

Eventually, they opted to reposition themselves as the real feminists, unlike what they started calling the traitors and the “Intersectionalists.”

What seemed at first like a desperate effort to hijack the movement, more recently turned out to be part of a greater attempt to force all those who are left into acquiescence. They are doing so by finding and “exposing” private information and photos of leading women who ran prominent feminist anonymous accounts. Many of these women run these accounts without their guardians’ knowledge and such exposure puts them at personal risks. As a result, several Twitter accounts with tens of thousands of followers were deactivated out of fear of reprisal.

A Victory and a New Beginning

At the time of writing this article, we did not expect that the movement’s main demand would be won so soon – on August 2, 2019, 1,114 days after the start of the movement, the core of male guardianship laws have been abolished.

This victory came in the form of changes to Civil Status, Travel Document, and Labor laws: The “head of household” has been redefined as both the father and mother, and “non-married women” have been removed from the definition of minors; adult women can obtain passports and travel without their guardian’s permission; married women no longer have to live with their husbands; the labor antidiscrimination article was re-written to outlaw all forms of sex-based discrimination in the labor market (which could open up new sectors of the economy to women’s participation.)

We wrote this piece with the expectation that it might take us years to get to that point, and did not expect to conclude on a much more hopeful note than was initially possible.

We still have a long way to go. The core of male guardianship laws was abolished but it is not fully dismantled. Fathers still have guardianship over marriage; child marriage is still legal; what is to happen to “Care Houses” is unclear; the kafala system remains in place; marital rape and domestic violence are both legal. Moreover, there seems to be no intent to establish institutional mechanisms to enforce even the legal changes made. Notably, our imprisoned friends and fellow activists either remain in jail or awaiting trial. The movement simply cannot stop here.

The feminist movement was the result of a combination of struggles by privileged women, who were fighting against the overarching legal systems that held them back, and mass personalized or localized struggles by women without any privileges, each having lived a life that had to be a political struggle against the manifold manifestations of oppressive and exploitative social relations. Since this movement was founded on the necessity of changing the everyday, we know that legal reforms, no matter how significant, to be insufficient.

In being the country’s first social movement that consciously broke through existing tribal, sectarian, and regionalist divisions that characterize most political currents in the country, it can be described as Saudi Arabia’s first nation-wide, mass social movement.

This character gives it both a largely (still) unexplored potential and forces it to deal with obstacles that no other movement had to deal with: establishing a nation-wide societal infrastructure for coordination, organization, and mobilization. The movement, we hope, is still in its early years.

References

| ↑1 | The other side of this same white supremacist coin is an implicitly racist cultural relativism: Muslim women’s oppression is still viewed as uniquely Muslim – an essentially cultural phenomenon that we cannot understand but should still “tolerate.” This is a precarious, unsustainable position, that sooner or later gives way to its more overtly racist expression. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Emancipation is never a linear process: reactionary forces cannot return to a past point in time, they can only move forward in a process of a reactionary negation of negation. |

| ↑3 | A. H., personal interview, Apr 7, 2018. |

| ↑4 | For example, in place of a conflict between the proletariat/oppressed and imperialists, Islamists presented a narrative of conflict between the downtrodden (mustaz‘afin) and global arrogance (al-istikbar al-‘alami). |

| ↑5 | These should not be understood as specific moment when a purely Islamic land/people encountered the “Western” capitalist other, but rather as a longstanding, ongoing process, in response to indigenous and exogenous social transformations. Different questions took hold at different historical conjunctures. For example, the Iraqi Islamic scholar Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr’s The Usury-Free Banking in Islam (al-bank al-la rabawi fi al-islam), and his Our Economy (Iqtisaduna), the foundational texts of Islamic economics, were written in the formative years of the postcolonial nation-states in the Global South, as a response to Marxist and capitalist economics. It is not the case that “usury,” for example, was largely not in practice in Iraq or the Arab world. Rather, this was a conflict over the legal ideological apparatus of the nascent postcolonial nation-state. |

| ↑6 | Care Houses (short for Houses of Social Care) primarily serve as prisons for “unruly,” “undesirable,” or “morally loose” women under 30, which includes forced “rehabilitation” services. Women over 30 are transferred to what is called “Houses of Hospitality.” According to accounts from women who left, systemic abuse includes weekly “routine” flogging, solitary confinement, and standing for long hours. Imprisoned women are denied access to electronic devices or any form of entertainment. There were several cases of imprisoned women escaping that gained national and later international attention, mainly due to the work of women active in the movement. Some of the movement’s early victories were in preventing their return to imprisonment. |

| ↑7 | Mohammed Dito, “Kafala: Foundations of Migrant Exclusion in GCC Labour Markets,” in Transit States: Labour, Migration and Citizenship in the Gulf, ed. Abdulhadi Khalaf et al. (London: Pluto Press, 2015), Kindle Edition, location 1719. |

| ↑8 | Omar AlShihabi, “Histories of Migration.” in Transit States: Labour, Migration and Citizenship in the Gulf, Kindle Edition, location 369. |

| ↑9 | AlShihabi, “Histories of Migration,” location 375. |

| ↑10 | Many migrant workers are stuck in jobs they do not want, since moving to a different job requires a transfer of sponsorship that must be approved by the Kafeel. Going back home is not a choice either, since, “more than three quarters of expatriate workers accumulated debt prior to traveling and hiring,” and this condition of debt bondage “limits workers’ bargaining power over the terms of the official work contract.” See Dito, “Kafala: Foundations of Migrant Exclusion in GCC Labour Markets.” |

| ↑11 | Before the ban was lifted, several new requirements were put in place for getting a driver’s license, which now costs nearly as much as the median monthly household income. |

| ↑12 | Since this wave of arrest garnered no media attention nor are there any public profiles for the arrestees to link to, we think it would be appropriate to briefly introduce them: Bader al-Ibrahim and Mohammad al-Sadiq are both prolific writers, who co-authored The Shi’i Movement in Saudi Arabia: The Politicization of the Sect and Stalinization of Politics (Arabic). Abdullah al-Duhailan is a journalist and a short story writer, who also wrote a book, Saudis and the Arab Spring (Arabic). Mogbel al-Saggar is a novelist, his novel Meem ‘Ayn (Arabic) deals specifically with women’s conditions in Saudi Arabia. Nayef al-Hindas is a writer, a translator, and an art critic. Khadija al-Harbi is a well-known feminist writer. Ali al-Saffar writes mostly on economics and Arab national sovereignty. Redha is a writer and photographer. Thamar al-Marzouqi and Abdullah al-Shehri, along with al-Duhailan, al-Saffar, al-Ibrahim, and al-Sadiq, among others, co-authored On the Meaning of Arabhood: Concepts and Challenges (Arabic); Fahad is known for his support for the women’s driving campaign. Sheikhah al-‘Irf and Ayman Aldrees are both translators. |

| ↑13 | Nearly all the activists mentioned in this article, for example, are known for their involvement in both feminist and pro-Palestinian advocacy. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine