However much upheaval the global COVID-19 pandemic has generated, a great deal more is coming. The economic disaster is already the object of frantic analysis, much of which tells us we can expect a bottom that matches or exceeds the Great Depression of the 1930s, at least as measured by conventional economic indicators like GDP, unemployment, and bankruptcies. This narrative provides the backbeat to the competing attempts to organize our attention during the passage through present and future trials.

While we are endlessly reminded that “we are all in this together”—a blatant act of false solidarity—many have also pointed out that we were never “all in this together” before the pandemic, we are not now, and it is quite possible we will emerge from this even less together than we were. At least in terms of wealth and income inequality, the prospects do not look good. The relatively well-off will weather the lockdown more comfortably and without the threat of eviction, debt default, and hunger, and they will return to better-paid and stable work more quickly.

The only way to avoid that is to think hard about the modes of economic organization we might take this terrible chance to transform. Green New Deals, permanent universal basic income (and health care where it does not already exist), and more radically decentralized means of provisioning and dignifying our collective lives—all of these things and more are possible. A background condition of these possibilities, however, is an economics that can underwrite and make sense of them. No economics could have “predicted” the pandemic; what matters is what directions it offers us in its wake. Even more than the financial crisis that began in 2007-2008, the pandemic has exposed the glaring inadequacies of existing economic policy, the absurdly fragile economics on which it relies, and the stunted conception of the economy that underwrites it.

In particular, it has turned a spotlight on the extraordinary uncertainty of this moment, of our state institutions’ and elites’ criminal underappreciation of the precariousness of the social regime over which they rule, and their utter and complete lack of a political economic analysis or vocabulary to understand the scale and substance of the current crisis. The economics that has dominated mainstream knowledge for decades cannot provide a fix for any of this. The insuppressible fact of real uncertainty, its kryptonite, has again proven all its expectations irrational. In an effort to explain how we can avoid reviving it, and what we can do to fight the efforts to reimpose it that are sure to come, it is worth thinking about how we got here, and why we can’t go back.

Macroeconomic “Revolution”

Twice in the last century, the world has forced macroeconomics to reinvent itself. First, the Great Depression dissolved economists’ widely-held faith in markets’ capacity to self-correct: if left to their “freedom,” not only were capitalist societies subject to “sub-optimal” conditions, but the freer the markets, the worse the conditions got. In the space created by John Maynard Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money of 1936 and the subsequent development of what would come to be called “Keynesian” economics, economists developed a new way of analyzing aggregate dynamics that understood crisis and instability as endogenous to market-based economies. The managed capitalism of the quarter century following the war put this “new” economics in the disciplinary and political driver’s seat.

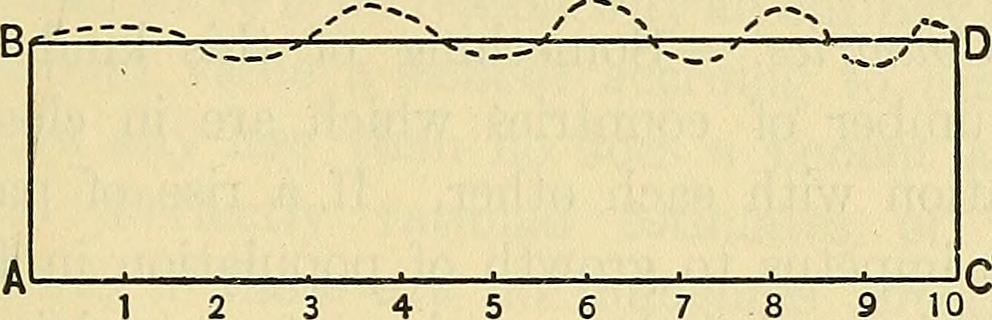

Second, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, this Keynesian consensus collapsed as the global economy stalled in ways it not only suggested was unlikely, but that it could not understand. The most glaring, and most famous, example of this failure is the standard Keynesian model of the relationship between inflation and unemployment—the so-called Phillips curve— which suggested the two were inversely related: rising prices reduce unemployment by stimulating production and vice versa. But by the early 1970s, both inflation and unemployment were rising in tandem, and attempts to slow one only seemed to exacerbate the other. By the Volcker coup of 1979–80, the “Keynesian revolution” had been put down, with most of the credit claimed by the so-called monetarist counter-revolution.

At least at a broad scale, these revolutions look a lot like the scientific revolutions Thomas Kuhn described in the early 1960s. Kuhn argued that science advances in a kind of punctuated equilibrium: most of the time, a field knowledge is characterized by a “paradigm” through which the main principles and theories are widely accepted. Scientific labour in these periods consists in the “normal” science of filling in the details or working out the specifics of this or that dimension of the system. Occasionally, however, the paradigm is undermined, and a “revolution” shakes the overall framework, during which a whole new way of knowing or explaining emerges, and the old is either left behind or shrinks from a general theory to a more provincial understanding of the world. The revolution is followed by a period in which the new paradigm’s “normal” dominates, and the pattern continues. In physics, for example, these revolutions are relatively well-known—those associated with Copernicus, Newton, Einstein, etc.—and each time, according to Kuhn, physics had to work itself out anew.

Economics is not quite a science—although in consolation it deems itself “the queen of the social sciences,” as MIT economist Paul Samuelson famously put it—but it is nonetheless earnestly and self-consciously revolutionary, even if its “revolutions” are less familiar to most of us than those of physics. While the plebeian social sciences generally experience substantial epistemological or methodological developments as mere “turns,” in economics they are true revolutions: the marginalist revolution of the second half of the nineteenth century and the Keynesian revolution are central events in the story mainstream economic thought tells itself of the last century and a half.

Revolution, of course, is a relative term. An intellectual “revolution” can take very conservative, even reactionary form: important threads in the Reformation, for example, were part of an effort to roll back the corrupt libertinism of the Catholic church and revive a more austere piety. The most recent of the self-described revolutions in economics, the “rational expectations revolution,” is that kind of revolution. It was the work of an influential free-market militia of macroeconomists supporting the monetarists’ counter-revolutionary assault on post-war Keynesianism. Perhaps the least familiar to non-economists, in the eyes of its protagonists it was the real revolution of the early 1970s, one most non-economists missed because their attention was trained on the (ultimately failed) project of monetarism. Many of the members of the militia were students of Milton Friedman, and like him, some went on to win a Nobel prize—Robert Lucas, Thomas Sargent, and Eugene Fama, among others—and much of their inspiration came from Friedman’s own 1960s work on inflation.

The fundamental claim of these rational expectation revolutionaries was not merely that we need to understand the role of agents’ expectations in shaping economic activity. That had been obvious to economists for decades. Much of Keynes’s General Theory is concerned with expectations, and many of his best-recognized contributions are essentially insights into the role perceptions of the future play in current economic decision-making. Effective demand, for instance, among Keynes’ most well-known conceptual innovations, is purely expectational: it is the volume of current production determined in light of businesses’ expected sales. Keynes’ point was that no business will purposefully produce more than its best guess at what it will sell: the aggregate estimate of future demand is the “effective” level for which firms produce. By the late 1960s, this was taken for granted even by non-Keynesians (it is part of what Friedman meant when he said “in some ways, we are all Keynesians now”).

The revolutionaries’ point was not only that actors develop expectations which determine their behaviour based on past experience, but that those expectations are rational in the economic sense: self-interested, anticipatory, and adaptive. In other words, in the interests of profit-maximization, businesses will not only try to estimate future market conditions, they will also anticipate policy changes that might affect their own and consumer decisions, and will get better and better at this as they learn over time. These were the “microfoundations” appropriate to a macroeconomics of capitalist individualism. This might not sound like much of a discovery, but its proponents insisted it meant (in the words of Sargent) “that no less than the field of macroeconomics must be reconstructed in order to take account of this principle of human behavior.” 1 In particular, it had to be reconstructed in non-Keynesian form because, like their teacher Friedman, they hated Keynesianism for justifying social constraints on the Darwinian dynamics of “economic freedom.”

It would be difficult to overstate the influence this way of thinking has had on macroeconomics, macroeconomic policy, and through it on the world over the last forty years. It sounds like the most minor of tweaks, but Sargent was right. It was definitely more than a “turn.” In fact, a lot of the basic principles of market-friendly economic policy since 1980 find their fundamental theoretical justification in the economics of rational expectations.

Their first and in some ways still most famous achievement was the construction of a more-than-merely-monetarist account of the failures of 1970s Keynesianism. Building on Friedmanite foundations, the militia diagnosed it as largely a result of an inadequate theory of expectations. The so-called “Lucas critique” demonstrated that the driving force behind the inflation-unemployment spiral of the early 1970s was that as the rules of the game changed—as the government tried to stimulate the economy by spending—market participants recognized it and changed their behaviour accordingly. They stopped being “fooled” by the stimulus and started expecting inflation, pricing anticipated increases into their plans. In the process, expansionary policy and expectations made inflation a self-fulfilling prophecy: people expected a certain level of inflation, priced it in to the market, and consequently realized their own expectations. The government, in turn, could only stimulate by exceeding expectations, which required further and further expansionary policy, which changed expectations, only driving inflation higher. As economists would say, the long-run Phillips curve is vertical: you can push prices up all you want but, in the end, unemployment will be the same. Policy cannot actually do more than pull off short-term “tricks”—beyond that, rational expectations neutralize it.

Rational expectations is also the foundation of the “efficient markets hypothesis,” which claimed that asset prices reflect all available information: rational market participants’ taking this information into account means that, adjusting for risk, prices reflect true asset values (they are “efficient”). The policy lessons of these two insights are enormous: (a) that in anything but the short term, expansionary fiscal and monetary policy is useless at best, and likely bad; and (b) financial markets efficiently allocate risk across market participants, and there is no such thing as a “bubble” (or at least no bubble that requires regulatory attention).

Since the “revolution,” the competition for macroeconomic theoretical hegemony has involved a series of pretenders to the throne—new classical economics, real business cycle theory, and most recently, “New Keynesian” macro—but all eagerly adopt rational expectations assumptions. These are now so central to the epistemological arsenal of, say, central banks, that to formulate a modern macro model without them would be unthinkable. For each of these variations on contemporary macroeconomics, regardless of its flavour, the market is the priority, precisely because it is the realm in which economic rationality is optimally expressed. It doesn’t matter if that market is characterized by perfect competition and information, as in real business cycle theory, or if it is subject to sticky prices and missing markets, as it is with New Keynesianism. In all cases, the market, and the market alone, is the medium through which stability is produced by adaptive, self-interested expectations in combination with clear and predictable rules of the game. So-called “credible commitment” to these rules is the government’s one inviolable responsibility. This is an economics for the production and maintenance of a market-based “normal,” in which prices are true, expectations are “anchored,” policy is “time-consistent” and institutions operate according to strict and universally recognized decision rules.

Clinging Irrationally to Rational Expectations

If this sounds to you like pre-financial crisis economics, you are correct. The key question now, though, as we confront another massive economic policy challenge in the pandemic, is how much it has remained post-financial crisis common sense. When much of the business press (and some economists) denounced the hegemony of rational-expectations thinking in the wake of 2008, the call for a “new” economics echoed in the halls of formerly puritan institutions from Davos to the IMF to the Bank of International Settlements. The “old” models did not take finance seriously enough (because we didn’t need to worry about it), they dismissed virtually all expansionary policy as an inflationary menace, and they implied that outside of enforcing property rights and addressing “market failures,” everything the state did crowded out the efficiency of free and rational market activity. They never saw the crisis coming, and it exposed their hubris in technicolor. Clearly, financial markets were tightly linked to the real economy, they were not efficient, and there was not a chance in hell “free” markets would endogenously generate an acceptable response to the chaos. Instead, the only thing that could assuage the crisis in expectations—the frozen-solid oligopolistic credit markets upon which everything else depended—were pretty-damn-close to Keynesian states’ panicked, scattershot, and ultimately condition-less intervention. The European Central Bank’s 2012 promise, in the words of its president Mario Draghi, to “do whatever it takes” is the polar opposite of market discipline and efficiency—two pillars of orthodox economics that capital had no interest in at the time.

A dozen years on, however, the “new” economics has still not arrived. In most of the economies of the global capitalist core there are new, mostly quite mild, regulations intended to soften future blows; central banks have developed a few new tricks of varying effectiveness, and the state’s backstop function is better institutionally embedded, if only in weak form. Policymakers’ models now try to account for financial “frictions”. But the main tenets of macroeconomics have not changed since the crisis, and most of them are constrained by the rational expectations straightjacket because it is still a key ingredient in the cookbook used to make sense of the world, despite its brief but stern dressing down.

This extraordinary influence operates especially through a particular way of dealing with uncertainty, an issue that Keynes did more than anyone to put at the centre of macroeconomics. In fact, one of rational expectations economics’ greatest achievements was to tackle uncertainty—something earlier classical and neoclassical economics had for the most part ignored. Part of the power of Keynesian political economy in the post-war world was due to the fact that in the wake of the Depression and war, it was the economic thinking that took the glaring vagaries of history seriously. More orthodox efforts to reclaim the throne of macroeconomic common sense were continually compromised by the fact that post-war anti-Keynesians had basically no compelling way to deal with uncertainty on the terrain of policy. On this front, the rational expectations militia came to the rescue, and have held the territory ever since.

This conception of uncertainty is bound, inseparably, to the ultimate meta-theology of modern economics: general equilibrium. General equilibrium makes a qualitatively different claim about the world than the basic notion of equilibrium we rely on in everyday speech. That notion is derived from physics, and usually event-specific or “static.” We drop a rock in the pond, and it produces a visible splash that ripples out and quickly disappears. We knock our heads against a hanging lamp, and it swings back and forth until it settles again. Even rudimentary economic thinking works like this: the supply-demand scissors all introductory students learn describes the way that supply and demand in a market reach an equilibrium this way. General equilibrium, however, refers not just to a general concept of equilibrium, nor even to a condition in which all the lamps have settled again. General equilibrium refers to the condition of the entire price system, when all markets for all goods are in equilibrium not merely in and of themselves, but relative to each other as well. In general equilibrium, if the price of one input changes, the others don’t necessarily remain as is, but change in response: all prices are relative prices.

What is crucial, though, is that this idea of an interdependent, economy-wide condition of equilibrium shares with our everyday notion the faith—the certainty—that things have a natural tendency to return to normal. Macroeconomics does not assume all market-oriented modes of economic organization are in equilibrium, but it does assume they tend inevitably toward it. Equilibrium is like gravity: it doesn’t mean you can’t jump up in the air, but it does mean there is always something pulling you back down. Viewed from the perspective of the long-run, then, disturbances are always absorbed by the system, perturbations hardly visible; ultimately, normal is the overall state of things.

It is one thing to say this about a rock dropped on the surface of a pond. It is quite another to suggest that the whole economy has a “natural” tendency toward general equilibrium. If this were indeed the case, then one might be tempted to describe the various possible “states of the world” with a probability distribution, any of which is understood as less likely, and less stable, the greater its distance from the central mass of the distribution. Consequently, it is possible to take uncertainty regarding future states of the world as accurately represented by probabilistic measures like “risk,” since states of the world can be assigned a measure of likelihood over time. Such measures assure us that, while the outcome of existing developments is uncertain, we can paradoxically be quite certain just how likely any particular outcome is. This allows us to operate with some confidence in our expectations about future states of the world, based on their relative probable impact on “normal” economic activity.

This is the intuition behind modern macroeconomic modeling, which matters enormously because modeling is the basis of economic forecasts and policy recommendations. The dominant macro-modeling method at present—so-called dynamic-stochastic general equilibrium models, or DSGE—was developed precisely to operationalize rational expectations theory, and to handle its probabilistic conception of uncertainty. DSGE models are designed to take account of the fact that reality is not static but dynamic: once markets reach equilibria, they don’t necessarily stay there. The models are also supposed to reflect the apparently “random” nature of much of real life: this is what economists mean by “stochastic.” Finally, these are, nevertheless, general equilibrium models, in which—despite its dynamism and stochasticity—the economy as a whole has a general tendency to pull toward order and stability.

From a rational expectations perspective, these models are useful tools for several reasons. First, they appear to embrace uncertainty. Not only is the future not assumed to be perfectly known, as in some earlier non-Keynesian models, but the whole apparatus is assembled to take account of the effect of “shocks” to the overall system. 2 Second, because economic agents are assumed to have rational expectations, they are in effect assumed to know how the model works. In other words, they know how things work, they know the rules of the game, and they know, or at least can learn, how to make decisions if and when those rules change due to stochastic events like weather-induced “supply shocks” or trade-war related “demand shocks.”

All the while, though, both the overall economic system and market participants’ own rationality are pulling things toward “normal”: if people expect things correctly, then they will learn that in general they are correct, and in acting rationally they will produce the outcome they expected. Rational expectations solve the problem of history by erasing it, because in the end, they are built on the premise that over time, what is expected will turn out to be true. Which is to say that on Kuhn’s terms, the rational expectations revolution’s “normal science” is the science of a free-market normal, and its models are only tractable if we assume that come what may, the train remains on the tracks and the engine is always pulling us forward.

This is the conceptual possibility frontier of contemporary macroeconomics, and in an era in which “normal” is an increasingly spurious category, it is an economics that is no help at all. It suggests that given current dynamics, possible futures can be assigned a probability in a system that tends toward stability, at least in the long-run. Consequently, it cannot anticipate or even conceive of what we might call catastrophic outcomes, which involve the disintegration or suspension of the system itself. There is no point inside the probability distribution indicating the likelihood that the probability distribution itself will become unmoored from the world it signifies, no point within the distribution that can represent an outcome beyond it. The best it can offer is to categorize calamity as a “fat-tail” exogenous shock—this is cutting edge climate economics—but even that is absurd, since what it tells is basically something like where x is the present and y is the future, y = ax ± who knows? 3 Anyone paying attention already knew that.

When, in the wreckage of the financial crisis of 2008 onward, even the Queen of England wondered out loud why the top economists in the world never saw it coming, the rational expectations economists were outraged. If their models were side-swiped and blown to pieces, that had nothing to do with the models themselves. The whole point of an unpredictable event, they fumed, was that it was unpredictable. No model of the economy could have told us what was coming. What they could not shout down, however, was the fact that rational expectations macroeconomics and its DSGE models could not only not predict the crisis, it actually insisted it was virtually impossible, or so unlikely that we needn’t worry about it. As Robert Lucas put it in his 2003 address to the American Economic Association: “the central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.” 4 If this is uncertainty, it is of a remarkably certain kind.

There is nothing in any of this, however sensitive to a limited range of external shocks, that can handle crisis, let alone a crisis endogenous to the system. All it could ever do, and all it ever did, was optimize capitalist “normal” for capital. This is why even so non-radical a policymaker as Jean Claude Trichet, President of the European Central Bank from 2003-2011, remarked that “in the face of the crisis, we felt abandoned by conventional tools.” Rational expectations theory and DSGE were foremost among these tools.

What Comes After Normal?

With the onset of the latest civilizational crisis with the pandemic, the limits to this conception of uncertainty, and to the state of modern economic thinking, have been exposed again, even more nakedly than in 2008. Just like then, mainstream macroeconomics of the rational expectations variety was the economics to which panicked policymakers first turned—lowering interest rates, providing “forward guidance” (the central bankers’ term for expectations-management)—only to discover immediately that it was of basically no use at all, and perhaps worse than that. Just like then, but even quicker, they hit the panic button provided by some crude variety of “Keynesianism,” in which the state is just one big, hastily-assembled pump spraying money at its closest allies (and a few workers). All other concerns—inequality, climate, Indigenous expropriation—are set aside in the interests of appearing to frantically do something.

The difference between 2008 and today, however, is that it is possible that when the virus has run its deadly course, economics and economic policy will not be able to go back to the last four decades’ devastating “normal.” The virus might—I want to say should—mean the death of modern macroeconomic orthodoxy, and of the policy regime it has underwritten. Perhaps it might even mean the end of equilibrium, at least in an epistemological sense. When climate change jumps back out of the political shadows when this emergency has receded, how can equilibrium, let alone general equilibrium, survive?

Economics’ defense when confronted with something like the pandemic is of course partly understandable. It is true that it would have been basically impossible to “predict,” if that means tell us it’s coming and when. It is equally true, consequently, that much if not most of modern economics, as a way of understanding and anticipating the unfolding of history, has little to offer right now. The best it can do is provide some basic statistical descriptions of patterns that are currently unfolding: the flight of capital from so-called emerging markets, soaring unemployment rates, or vague estimates of GDP losses over the next six months or a year.

But if the two most recent supposedly once-in-lifetime global crises have taught us one thing, it is that modern economics is built for an increasingly illusory and brutally unequal normal, in which uncertainty and expectations are bounded by “reasonable” limits, for a world in which a well-managed (market-based) normal chugs along, occasionally buffeted by “shocks” that are always framed as exogenous. How useful is this in a world in which the line between normal and crisis has broken down, and natural, social and geological processes are so clearly interdependent? Beyond the simple inside/outside rigidities of modeling, it makes no sense to say the coronavirus pandemic is “exogenous,” when it is clearly a product of the elaborate and unequal network that constitutes global political economy. As people like Mike Davis have recently remarked, the pandemic is better understood as a product of the political economy and ecology of global capitalism: marginalized workers and consumers in the global South were necessarily the ones likely to initiate transmission, because they are the ones who still do the risky low-wage work close to nature. The instantaneous and unregulated networks that constitute global exchange penetrate the entire hierarchy, and make transmission virtually unstoppable. And forty years of liberalization, privatization, and the abandonment of public institutions of collective welfare meant that when it arrived, there was very little left to mobilize.

The result is bad for everyone except Amazon profiteers, obviously, but as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and many others have pointed out, it is particularly vicious for those the system has long done its best to crush. As David Harvey puts it, “the progress of COVID-19 exhibits all the characteristics of a class, gendered, and racialized pandemic”—and as Indigenous peoples the world over struggle to manage the coronavirus contagion on top of everything else, we must of course add “colonial” to this list.

But the hegemonic rational expectations-based macroeconomics that has organized so much economic policy in the neoliberal era is an economics designed explicitly for a world in which the pandemic never arrives. What’s more, decades of intellectual and distributional dominance eventually gave it the impression that if the way of the world fit the model, and if “shocks” to the model were rationally anticipated by the users, we should act as if it will never arrive—anything else would be inefficient, and send the wrong signals. Now that it is here, we are told economics is not to blame, and if we need some emergency measures like a few doses of “Keynesianism” to get through it, there should be no misunderstanding that once we are “back to normal,” the economics of normal will return.

For a variety of reasons both logical and mythological, this is pretty much how it worked out after the financial crisis. As Adam Tooze and many others have said, however, this time there can be no going back to normal: “If radical uncertainty was a concern before, it will now be an ever present reality.” But it is not just true uncertainty that will hinder a return to an economic normal. The pandemic has destabilized not just those dimensions of the world we conventionally think of as subject to economic policy. As the days pass, the breach is increasingly experienced as a vacuum, and that vacuum will be filled. On the exciting side, movements are organizing to reinvigorate the collective project, and prevent the reimposition of market discipline and unequal access. But we are already hearing rumblings of the belt-tightening that will be required when the worst has passed, the bleating of inflationary hawks who some people still seem to listen to. Other forces are eagerly seizing the opportunity to extend the surveillance apparatus, build even more inaccessible islands of privilege, lock-in disastrous fossil fuel infrastructure, and villainize immigrants and others to inscribe a mythical “purity” on the national body. Normal won’t return because it is already passed, another victim of the pandemic.

What comes next, however, is by no means clear, and by no means necessarily welcome. Just because the last “revolution” in economics has turned out to be so catastrophic and ill-suited to the unequal, ecologically-degraded and undemocratic world it gleefully helped produce and angrily defends, that in no way means that what’s coming must be better. History suggests that a scientific “revolution” can leave some of the most pernicious aspects of its common sense untouched.

Much of the challenge on the economic front right now lies in how to transform that common sense. For instance, one of the things COVID-19 has made irrefutable is that at least in the realm of life’s necessities, the market is a totally inadequate instrument of distribution. But without considerable work at both the institutional and political-ideological levels, that lesson will not stick, but will instead fit easily into the narrative of a normal temporarily undone by an exogenous “shock.” Contemporary macroeconomists would say that this is a “market failure”—the failure of markets to play their efficient distributional role—but it is actually a failure of markets, and a direct result of the work of more than forty years of economic policy. When you believe no one else will support you, and when markets are not just the central, but the only resource allocation mechanism in societies, panic-buying and hoarding make perfect sense.

If this experience gets logged into the historical record book as mere “shock,” then next time, one of the first things many people will have learned from the pandemic is that because the market is so cruel, the smart response is to hoard earlier and faster. They are a product of, not an aberration from, market-dependent life in terrible times. What’s worse, the point of contemporary markets in those times is not to prevent panic, but to fan the flames. In our just-in-time world there is only ever enough medicine, masks, life support, or toilet paper because there is never supposed to be enough. The point is only to plan for a profit-maximizing normal. Firms don’t respond to panics to bravely or altruistically restock the shelves for the old lady who went with nothing, but to feed the panicked mouth. If the goal was to get necessities to those who need them, no one would be burying tons of “surplus” foodstuffs because restaurants are no longer buying leeks and onions.

Some of the work to move common sense, to show how “endogenous” the lived reality of the pandemic is, is already underway. Most of it, of course, is happening outside the realms of economics proper. Neither the Defence Production Act, nor international swap lines between central banks for dollar funding, nor bottomless quantitative easing undermine that common sense; on the contrary, these measures buttress it by framing the entire rescue operation as an exception that will eventually fade away against a background of normal. Where the dying economic common sense is losing grip is outside the categories that economics uses to think about the economy, the result of work being done closer to the ground. Mutual aid groups have sprung up all over the world, helping those in need of support. While it might have been obvious to the people who do the work, many of us are recognizing for the first time in our lives how crucial supposedly “low-skill” labour is not only to the functioning of the economy, but to our everyday well-being, and how surprisingly expendable much so-called “skilled” and professional work turns out to be. The taken-for-granted hierarchies are unsettled, and ripe for a toppling.

Among the more complex dimensions of the challenge to more radical transformation at the moment, however, is that it seems to me to require using the institutional, political and conceptual apparatus at hand, because too many folks are in desperate and immediate need, and for many of them it is access to this apparatus that appears to provide their best chance of managing the turmoil. Normal might have been exploitative, even punishing, but it was also somewhat familiar, and was for lots of people the only means, however inadequate, through which to confront necessity. A qualitatively meaningful and just transformation is entirely possible, but in the near-term it must manage demands on which the capitalist everyday of jobs, housing, education and health is supposed to deliver, even if it never did for so many.

This will not be easy to organize and achieve, at least partly because of the hold that vague thing policy called Keynesianism currently has on the way capitalist societies think about emergency. The last decade has shown that something like what most people think of a Keynesianism—government stimulus, rescue funds, low interest rates and occasionally income or unemployment relief—is the de facto shared panic button of capitalism’s greatest admirers and some of its staunchest critics. The specifics matter enormously, of course, but crowded together at the edge of the precipice, it is the one thing on which a general agreement has emerged. Yet however “revolutionary” its economics, Keynesianism has rarely been about radical or even significant social change. It has virtually always been a rescue operation to salvage a civilization of a particularly bourgeois flavor, an elaborate legitimization program. In Keynes’s own mind, it held open the door to a far-away post-scarcity economy, but even if we take his rosy projections of the “economic possibilities for our grandchildren” at face value, that vision is miles from today’s Keynesianism, and especially from its current New Keynesian macroeconomic version.

All of which is to say that if we hear about the return of Keynesianism, we should not relax one bit. It does not mean everything will be fine, and it definitely does not mean that any of its supportive measures, however discriminatory and inadequate, will last. Instead, the “new” economy cannot be merely Keynesian, because it has to be a rescue operation for those who had been thrown off the boat long before the pandemic. The new economics cannot dream of some Pareto-optimal normal, which has never been anything more than an arrogant just-so story. Even when we have escaped the clutches of the virus, we will remain beholden to a concatenation of permanent emergencies for which most of contemporary economics has already proven itself almost totally useless. The new economics will have to be more wary, more place and time specific, more deliberate, and probably a lot slower and more “costly.”

The question, of course, is who bears those costs. I can guarantee you that if the economics of the last forty years retains its dominance in policy and beyond, it will be the same people who have been bearing them for so long: the poor, the marginalized, and the unwelcome. The economics that must replace it won’t be a fully-formed “school,” and it won’t be “rational” in the narrow disciplinary sense, but an experimental, adaptable and bold patchwork. If we look around, we can already see people planting its seeds. The task ahead is to water them, and make sure they get lots of light.

References

| ↑1 | Thomas Sargent (1980) Rational Expectations and the Reconstruction of Macroeconomics, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, Summer. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | These shocks are very different from those Naomi Klein describes in The Shock Doctrine, which are intended to radically reset an economy to put it on the path to a capitalist “normal”. Macroeconomics’ shocks are the bumps in the road that “normal” faces once it is up and running. |

| ↑3 | It will surprise no one that the integrated assessment models that are the mainstay of contemporary climate economics are general equilibrium models, sometimes of the DSGE variety. |

| ↑4 | Robert Lucas (2003) Macroeconomic Priorities, American Economic Review, vol. 93, issue 1. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine