Before it was even built, Barclays Center in Brooklyn was a matter of contention: it was opposed by grassroots groups, which correctly feared that it would end up further driving the racist gentrification of an area already undergoing rapid change. These groups further denounced the $1.6 billion in public funds swallowed up by the project, and Barclays was generally hated by drivers who saw the enormous construction site transform Atlantic Avenue into a years-long nightmare. These days, Barclays has become a hot site of conflict again. For the past week, an ever-growing crowd of protesters, young and multiracial, has been gathering in the square in front of Barclays like clockwork, every day at 6pm. While initially there were official announcements, most days people simply went to Barclays at 6pm, trusting that a crowd would be protesting there even in the absence of an announcement. They have not yet been disappointed.

On June 4th, the Barclays meeting point appeared to undergo the legendary transformation of quantity into quality, possibly as a consequence of the repeated contact and exchange, over the course of days that felt like months, among protesters on the ground. In fact, at Barclays on June 4th, one could glimpse the first signs of a political subjectivity emerging through still-embryonic and spontaneous processes of self-activation. Around 6pm, as groups of people continued to join the 500-strong crowd, the gathering rapidly morphed into a sort of improvised general assembly or open mic: speeches followed one after another, but these were not the routine and often predictable speeches of members of political groups at organized rallies. They were mostly spontaneous expressions of rage, love, solidarity, hope, gratitude, and radical political analysis, from random protesters, people at their very first experience of struggle, and a few leftist veterans. Among the cheers of the crowd, which was carefully listening despite the absence of an amplifier, a homeless Black man in his fifties gave a perfect materialist analysis of the dynamics of the social unrest: “For the first time in years we are seeing a mass revolt of white people in support of our struggle, and this is happening because of the economic crisis, because white people are now getting declassed.” A brown transwoman passionately addressed brown cismen: “If you can’t stand for your trans brown sisters, get the fuck back home. Our enemy is the same, we need to stand in unity.” Her speech was welcomed with an enthusiastic ovation. Had someone organized this open mic? Most likely not, or at least no leadership was recognizable except for the leadership of young Black and brown women and men organically emerging over the course of the evening from the protest itself.

At 8pm, a crowd of 3000 people joined with a splinter march from as far south as Sunset Park, and started chanting in unison: “Fuck your curfew.” The intention was clear to everybody there: they would hold their ground and stay in the streets as long as possible, until mass arrest if necessary. With this intent, the march started to move, changing direction at every turn, playing a game of cat and mouse with the police. The more the NYPD tried to get ahead of the march in order to kettle, disperse, or arrest protestors, the more unpredictable its route became, from Barclays to Cobble Hill, back to Barclays and then Fort Greene, and finally Clinton Hill. Who was leading it? Probably a group of protesters who had been going to Barclays over the past several days, who had then decided to take charge of the tactical coordination of the protest. Perhaps a provisional affinity group. Maybe simply a collection of individuals who decided to take charge for the evening.

At Barclays a group of protesters had a little table with fruit, snacks, legal information, Gatorade, and hand sanitizer; others had bags filled with care packages (with a face mask and hand sanitizer in addition to food and energy drinks) which they distributed liberally to the crowd. At some point during the march, a car arrived out of nowhere and stopped in the middle of Atlantic Avenue, and a Black man descended and opened a trunk filled with cartons of water. More people could be seen distributing water and energy drinks in the streets of Cobble Hill, Fort Greene, and Boerum Place. Who had organized this impressive mutual aid infrastructure, which made sure that protesters would have the energy to carry on for as long as possible in New York City’s terrible humidity, and the vitamins to fight off Covid-19? Nobody and everybody: it was likely a combination of the work of some grassroots groups, a spontaneous expression of solidarity with the protest, and the coming together of groups of friends, acquaintances, and comrades to raise funds, prepare care packages, and position themselves along the ever-changing route of the march.

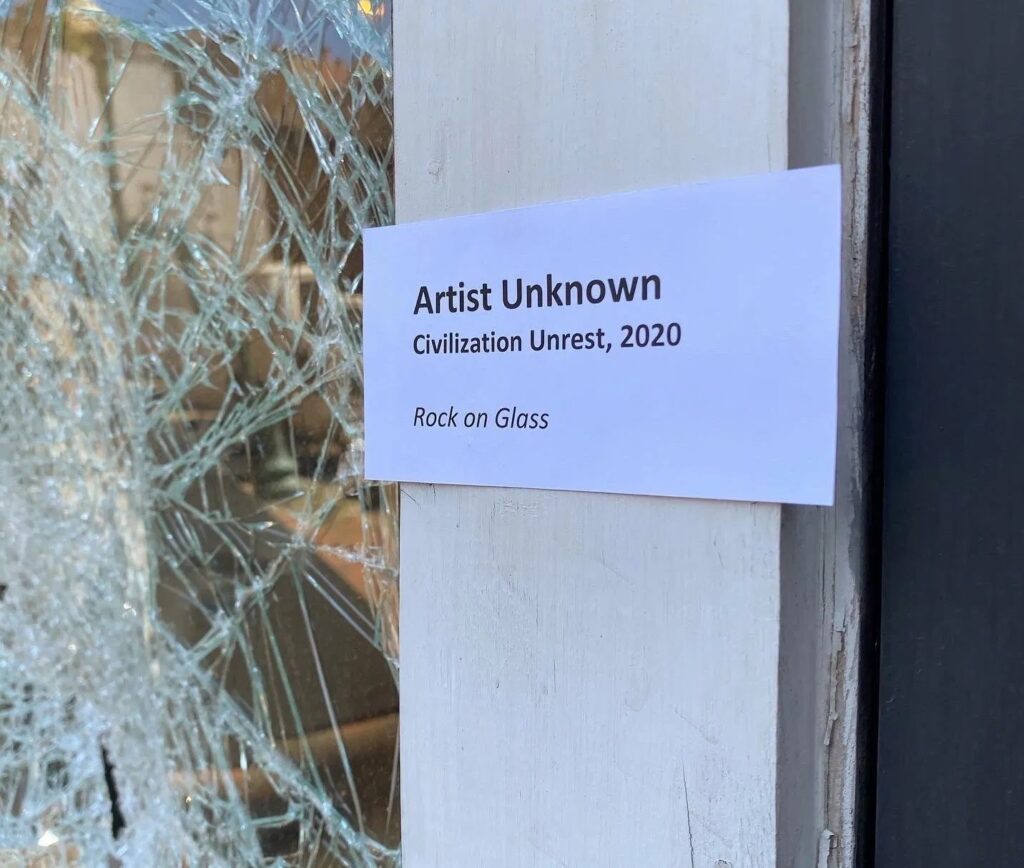

This collective act of care — or of radical (and mobile) social reproduction from below — was matched by the overwhelming solidarity expressed by the city itself. Cheers welcomed protesters from every building of every street through which they marched, and people stood outside of their homes, in defiance of the curfew, to watch, raise their fists, and be as noisy as possible. An ambulance stopped in the middle of the street and the Black first responder in it grabbed the intercom to salute the march and chant. An artist arrived with her car to distribute beautiful black-and-white signs, and then left. And, then, in a bizarre and ambiguous moment, a traffic police in a tiny little car honked her horn and threw her first up, encouraging protesters to ‘keep going. As the march kept snaking through the streets, hour after hour, the whole city seemed to want to embrace it, salute it, give it strength, tell the protesters that they too would be in the streets if it were not for the pandemic, if they had not already been at another of the multiple daily NYC marches, or if they did not have kids at home. And then there was the comic absurdity, the situationism, and the creativity (from absurdist outfits to hilarious signs) that only gets unleashed in moments of collective liberation, where capitalist normality gets suspended and people get a taste of a different kind of freedom. Beauty was back in the streets.

These ten days, which are shaking the country in a way that has not happened for fifty years, have condensed and accelerated time: it is only ten days, but it feels like ten months. The state of suspended tension of the long months of the lockdown has given way to collective exhilaration, rage combined with beauty and love: for fellow protesters, for the more than 100,000 dead of the pandemic, for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Jamal Floyd and the countless Black lives taken away by a militarized and racist state, and for our future, which we thought had been stolen from us and which we are now re-appropriating for ourselves through the struggle.

And yet, the challenges ahead are many, and difficult to tackle. Barclays saw the spontaneous emergence of the conditions of possibility for a collective process of self-organization and subjectivation. But these are only conditions of possibility, potentialities to be realized. Self-organization, however, is key to the durability of this social revolt, to its expansion to additional social sectors (beginning with organized labor and workplaces in general), to its capacity for self-defense against brutal repression, and to its ability to maintain political autonomy from the forces of cooptation and absorption that will inevitably try to tame the revolt and perhaps transform social rage into votes. While another Trump presidency would be a disaster, not least because of its galvanizing effect on the far-right worldwide, from India to Brazil, it is also the case that ten days of social revolt have done more to dismantle institutionalized racism than eight years of Obama’s presidency. It is this collective power that is being rediscovered by this social revolt. And it is the political autonomy of this collective power that we must zealously preserve.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine