Painted in bold against the outer walls of the Margaret McMillan building at Goldsmiths, University of London, an inscription in memoriam of Mark Fisher reads, “Emancipatory politics must always destroy the appearance of a ‘natural order’, must reveal what is presented as necessary and inevitable to be a mere contingency, just as it must make what was previously deemed to be impossible seem attainable.”1 If these words cut hard against the currents of education as Fisher saw them before his death in early 2017, in which metrics of productivity and excellence coincided with foreclosed conceptions of public goods and abundance to the detriment of personal and collective wellbeing, they do even more so today. Though tagged on its brick and mortar, the mural does not stand representative of Goldsmiths as an entity but in contradistinction to it, much despite attempts by College management to recuperate and commodify the intellectual and political projects of its workers and students. Framing their ongoing drive to push through a restructure based on increased high-salaried managerial positions, reductions of administrative and teaching staff, and growths of student numbers to finance the institution on their debt, the current Warden and Senior Management Team (SMT) pitch Goldsmiths as “a beacon of progressive, liberal values” that throws “a searchlight on some of society’s biggest problems.” With their restructure exemplary of the entrenchment of austerity that Fisher recognized as all pervasive, the values management invoke read as no more than hollowed, marketable abstractions seeking normalization among incoming student cohorts who may have never experienced the conditions of education differently. Management’s so-far relentless mission since early 2020 to execute a restructure no matter the strength of trade unionist opposition seems revealing of an objective of institutional depoliticization waged in the name of progressivism.

Responding to an ongoing dispute with the Goldsmiths University College Union (GUCU) which already saw three weeks of strike action during the 2021 winter term, SMT issued a statement on January 10th 2022 in which they doubled down on plans to make up to fifty-two “permanent” staff redundant across the departments of English and Creative Writing (ECW) and History by the end of the spring term. These redundancies were proposed as just part of the initial phase of an SMT-driven “Goldsmiths Recovery Programme”—a euphemism for a College-wide restructure. Spearheaded by Frances Corner, Warden (or Vice-Chancellor) of Goldsmiths since 2019, the Recovery Programme was officially unveiled in September 2021 to allegedly redress former economic mishandling of the College while repairing financial damages endured in the COVID-19 pandemic, and was announced with SMT’s motivation to “improve student experience” at the College while reversing a £12.7 million deficit into a surplus.

Since its first appearance, GUCU members have continually labeled the Recovery Programme as an ideological restructure driven not by genuine economic necessity but as an assault on worker security, as well as teaching and research autonomy, in an effort to increase annual profits and consolidate managerial power within the institution. With an overall goal to save £9 million over two years, an initial target for 2022 was set by SMT for £6 million. Two thirds of this were to be achieved by savings from academic departments and the centralization of “professional services” (administration in the US context). The remaining £2 million was to be gleaned from non-pay decreases elsewhere in the College budget. In September 2021, ECW and History were announced as the first targets for job cuts for already falling short of compulsory departmental savings contributions, with the equivalent of twenty full-time academic workers to be made redundant and up to thirty-two dedicated departmental administrative posts to be “deleted” (as described by SMT in an email to constituent staff). GUCU considers the latter effort a “fire and rehire” scheme set to deskill workers reinstated in a limited number of more atomised roles and to disproportionately affect those who identify as BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) and as women. Academic dismissals would be determined based on “rank and yank” tactics, requiring workers to complete a metrics-based “Skills Match Questionnaire.” The lowest “scoring” academic staff would be marked for redundancy.

An additional and pivotal aspect of the Goldsmiths Recovery Programme is the establishment of an institution-wide “connected curriculum” of compulsory undergraduate modules, planned by SMT to be in place by September 2022, to affect teaching practices, content, and learning objectives across the College. With titles such as “Goldsmiths 101,” the curriculum is allegedly designed to reflect the institution’s supposed values and “mission to promote equality, diversity and inclusion,” all while BAME workers across departments affected in the restructure face unemployment, including academic staff who designed and teach on the UK’s only Black British Literature, Black British History, and Queer History MA programs. The restructure’s landing page on the Goldsmiths website mentions an “expectation of the continuation of areas including Creative Writing, Black British History, Black British and Caribbean Literature and Queer Studies as vital areas of academic endeavour” alongside “traditional areas of strength like the environment, civic responsibility and social justice”—pledges management see as achievable without commitments to the livelihoods of workers.

The connected curriculum has received resoundingly negative responses from internal feedback solicited by SMT, and has been conveyed by workers as an embarrassingly simplified amalgamation of research topics extracted from faculties across the College. A lecturer from the department of Sociology, for instance, describes “Goldsmiths 101” as “proposed in sheer ignorance… Firstly, ignorance about the social sciences and humanities taught by us… Secondly, there is a blatant and appalling ignorance about students and their life experience and plurality of interests and concerns.” Sketched as three compulsory centralized modules for most undergraduate students, forty-five credits—the equivalent of three modules—would consequently be subtracted from departments for each student enrolled on one of their degree programs. Hypothetically, the effect of a reduced demand for departmental modules would provide more scope for SMT to identify “underperforming” programs. This would pave the way to further redundancies in conjunction with the connected curriculum’s “digital first” delivery (i.e., partially automatable online teaching), and therefore present a means for SMT to in part reach their remaining £3 million savings target. As Goldsmiths undergraduate degrees are currently largely based on option modules, the compulsory curriculum would also detract from students’ abilities to develop their own research practices, effectively assaulting their autonomy over their own education. In another review, a lecturer from the department of Media, Communications and Cultural Studies claimed that student feedback on the connected curriculum has been “uniformly negative,” and quotes an undergraduate as saying, “[i]f this goes forward, I will be utterly ashamed for having this institution’s name on my degree.”

The SMT statement of January 10th insisted that no viable savings alternatives to redundancies had so far been proposed by workers of ECW or History. Management announced that it would therefore “commence its original proposal to reduce staff numbers as the way to close the financial gap” posed by the departments. This statement was taken to blithely disregard measures proposed by GUCU to save staff positions—such as rescinding plans to create new high-salary management roles, another key feature of the restructure2—without an explanation as to why such proposals were not considered “viable” in the short to medium term. Repeated declarations by SMT that redundancies are “always a last resort” were ultimately contradicted by March of this year, when it was revealed that by the voluntary severance of dozens of staff —and subsequent unfilled vacancies noted as close to double the number of positions marked for forced redundancy—enough savings had been generated at Goldsmiths to significantly reduce if not completely halt compulsory job cuts. Instead of doing this, GUCU reports, savings have been continually redirected to fund an interim “change management” team, consultants from the corporate sector with no long-term interests in higher education, hired to oversee the restructure and redundancies process.

* * *

GUCU has declared SMT’s continuous refusals to cancel unnecessary job cuts as exemplary of institutional violence at Goldsmiths, and indicative of autocracy that follows managerialism, by which decisions are carried through on principle no matter the cost inflicted on those below. SMT’s expressions of regret for those affected by redundancies, meanwhile, stand in contradiction to the material effects of the policies they themselves design and implement—from the evisceration of individual access to waged work to increased workloads for remaining staff. If, as a recent article in Tribune magazine claims, current events at Goldsmiths present a microcosm of working conditions across the higher education sector, it is this that has become most recognizable amidst SMT’s restructure: the degrees of violence to which workers and students alike are subject in the corporatized austerity university.

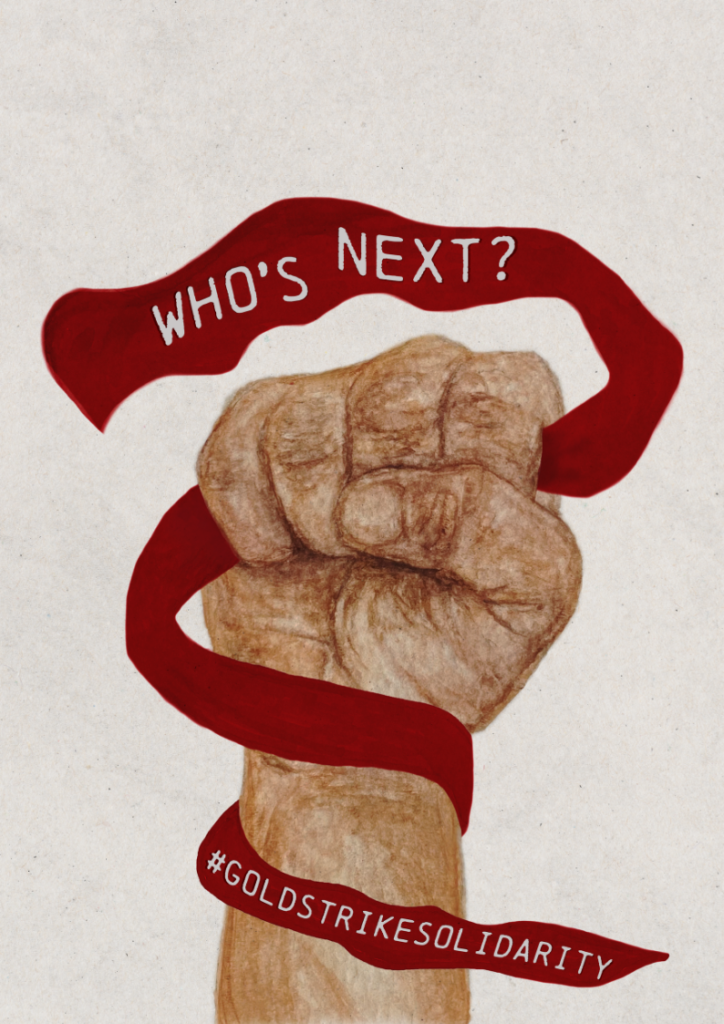

Worker struggles against the Goldsmiths Recovery Programme were escalated in early 2022 and have reached unprecedented extents even against the backdrop of some of the largest ever coordinated actions of the national University College Union (UCU). In March 2022 alone, up to fifty-thousand workers across sixty-seven universities went on strike as part of the national “Four Fights” campaign. By that same month, almost eight out of twenty teaching weeks of the 2021–22 academic year at Goldsmiths had been absorbed by strike action in a local campaign for no job cuts, no connected curriculum, and no institutional restructure without meaningful consultation and involvement of all workers. Just days after SMT’s January 10th statement, the UCU issued an international academic boycott and gray-listing of Goldsmiths, appealing to researchers of other institutions to cancel or relocate events scheduled at the College, to refrain from submitting to its publications, and to refuse new contracts as its external examiners. Such a move is described by the UCU as their “ultimate sanction” against an institution and, considering the lasting reputational damage that may follow, one only issued as a last measure against egregious displays of institutional violence.3

Despite the breadth of industrial action at Goldsmiths, SMT’s strategy has evidently been to hold steadfast in the assumption that once the initial force of worker outrage against the restructure has been exhausted, so too will the organized response subside. Just after 7pm on Friday, April 8th, the eve of an Easter-period recess, redundancy notices were issued by email from SMT to sixteen staff members of ECW and History. The majority of academics who received dismissals are active trade unionists, including departmental reps and a serving co-president. The fact that, at least so far, the number of redundancies issued by SMT have not come near the initial projection is not a point of celebration for GUCU members. Grief and exhaustion are palpable among staff and students at Goldsmiths, yet determination to continue the fight against the restructure has been bolstered by the example set by the University of Liverpool UCU, which in a 2021 dispute overturned the compulsory redundancies of forty-seven academic staff members after termination notices were issued by management.

As an ongoing struggle, the situation at Goldsmiths is difficult to analyze comprehensively, as is its end result difficult to predict. Having never entered one before, GUCU is currently in its third local dispute under Frances Corner’s governance, with worker organizing across those motions now stretching beyond three academic years. As of April 2022, GUCU members have reballotted at 87.5% to extend the current dispute period and take action short of strike (ASOS) over the summer term, with publicized tactics including a marking boycott and non-compliance with the connected curriculum. Additionally, there has been a reballot of 78% to resume strike action in the 2022-23 academic year. A single industrial motion covering two academic years is, once more, unprecedented in the history of the UCU. Outwardly, the sequence of events at Goldsmiths may be read as a demoralizing series of defeats, by which SMT continues to erode worker security irrespective of organized opposition, made all the more disheartening by mass resignations—with many citing toxic working conditions under current management as the reason for their voluntary departure. The stakes of the struggle are also revealed just here with two potential outcomes: 1) For SMT to realize their restructure, erecting a more violent institution while flagrantly working to impair future oppositions by reducing the workforce and targeting trade unionists for redundancy; or 2) For the dispute and boycott of Goldsmiths to mark not simply the unmatched extent of one local pushback but the mere beginnings of a protracted labor campaign to be sustained against the university in its current form—and perhaps against worker-governability by the managerialism that now characterizes higher education. It may only be possible to see the struggle defined by the defeat of one side in the presumption that its ends are within sight.

* * *

Mere yards from Fisher’s words on the central campus of Goldsmiths on Lewisham Way in South East London, one can now find on the New Cross Road high street the prospective site of an “Enterprise Hub,” a renovation project set in motion following the appointment of Corner as Warden. Set to cost the institution upwards of £4 million, the same figure planned to be saved by staff redundancies and administrative changes in the more recently conceived restructure, management’s proclaimed goal for the Hub has been to build “a local community of entrepreneurs and support business-start up and growth.” Although indefinitely paused as an outcome of industrial dispute, the conception of the Hub is emblematic of a broader vision for the transformation of Goldsmiths into an institution that reflects the political economy of fully marketized higher education, in which a university qualification is foremost a transaction and a marker of personal investment and self-entrepreneurialism.

Goldsmiths is no outlier in the fact that the so-called financial health of UK universities has become dependent on student fees and recruitment growth since the 2010 Browne Review.4 By the review, block grants that formerly subsidised undergraduate education were slashed and student fees—only reintroduced for the first time since the 60s under Blair’s 1998 government—were almost tripled and capped at £9000 per year.5 This event prompted the renowned UK student revolts of November 2010. In that year, around 44% of Goldsmiths’ reported income was comprised of student fees, while around 39% was composed of grants. By 2020, tuition fees stood at approximately £9250 per year per home-rated undergraduate student and accounted for 77% of income. Funding council grants made up just 9%.6

Peter Fleming points out that as universities came to be financed on student debt—in accordance with policy designed by people who received degrees during a time in which public university attendance was free—so increases the impulse to see a return on investment in education. From this tendency follows an attack on education for its sake, particularly within the arts and humanities.7 This arises at individual level, as students become “consumers” in an educational transaction, and from policy makers keen to see graduates pay off state-issued student loans.8 As a result, remaining government grants are prioritized for university departments that specialize in STEM fields while the arts, humanities, and social sciences receive less year on year. UK universities are now also subject to government fines if less than 60% of recent graduates do not secure “skilled employment” within the first year of completing their college course. As such, higher education is ever less provided as a social good than for the tending of human capital, or the production of homo oeconomicus, for future returns in economic circulation, while arts and humanities curricula must increasingly prove their applicability on the market and the “transferability” of the skills they cultivate.

Considering all of this and the managerialist turn that has also defined higher education post-Browne Review,9 SMT’s promotions of business growth and enterprise are hardly surprising. They also fly in the face of governance models previously proposed by a staff-and-student collective seeking to position Goldsmiths “at the forefront of re-casting the university” as a public good and to set a strategy to lobby the state for alternative funding mechanisms.10 Instead, the emphasis under the current Warden is to teach in the areas of social justice, ethics, and diversity, so that they may, presumably, be applied elsewhere on the job market. The paradox that the employment stability of those who teach and support learning at Goldsmiths is negated so that more students may earn degrees from the College to, also presumably, buy themselves a level of future security is overlooked by management.

Similarly premised on job cuts and SMT expansion, an earlier iteration of the Warden’s restructure was circumvented by worker organizing in 2020. Formerly the head of the London College of Fashion and Pro-Vice Chancellor of University of the Arts London—which saw a restructure similarly based on job cuts imposed in 2017—Corner sought to establish her position at Goldsmiths on campaigns of ethical business practices and an institutional “Green New Deal.” (The latter was seen by many on the ground as tied to a green-washing PR scheme following a 137-day student-led “Goldsmiths Anti-Racist Action” occupation of Deptford Town Hall, a campus building just doors up from the future site of the Enterprise Hub. Within a month of the occupation’s end, which happened after management threatened to pursue the legal eviction of students demanding that the College address institutional racism, SMT began rebuilding the Goldsmiths brand as a forerunner of decarbonization and fossil-fuel divestment.) The Warden’s vision of a business of care was undermined early in her tenure, when in January 2020 an “Evolving Goldsmiths” agenda was circulated by SMT to unexpecting staff to announce a plan to reverse an institutional deficit of £10 million to a surplus of £2 million within three years and achieve financial sustainability by 2030.11 As the precursor to the pandemic Recovery Programme, Evolving Goldsmiths was also purportedly motivated to produce an improvement in student experience while correcting the institution’s financial standing. The agenda stipulated for the first time the construction of the Enterprise Hub, the creation of new senior management positions, and a 15% cost reduction from academic and professional services. Also introduced in late January was a “Voluntary Severance Scheme” open to all to lower staff numbers without yet forcing redundancies.

Identifying serious flaws with the financial rationale of the scheme, GUCU immediately and vehemently disputed SMT’s claims the Evolving Goldsmiths was designed with “radical transparency.” For example, workers questioned why ten years were required to achieve economic stability when budgetary deficits at the College had been reported for just three. In a financial analysis of the plan, GUCU noted that the reported deficit was not based on massive income losses but a failure to meet projected growth, including a targeted 5.3% increase in student fees income despite mitigating external and internal conditions—from Brexit to individual departments hitting recruitment capacity without the provision of further teaching resources.

Following the establishment of an official union dispute and a local ballot to escalate demands for no job cuts and no SMT-dictated restructure, the Warden announced the “closure” of Evolving Goldsmiths via email in April 2020. In the wake of COVID-19, however, she simultaneously gestured to the development of a “recovery plan” for the College to withstand financial losses caused by the pandemic. The voluntary severance scheme was also retained and ultimately extended to March 2021. Although welcoming an end to Evolving Goldsmiths, staff quickly expressed skepticism of the recovery plan, claiming that it would be meaningless for a restructure to be canceled if its significant features were to reemerge beneath another name.

Suspicions that elements of Evolving Goldsmiths would reappear simply rebranded materialized in 2021—after Corner and SMT had received an 87% vote of no confidence from academic workers. In the vote, it was asserted that management had lost all credibility in the aftermath of the first restructure scheme and for proceeding with unpopular plans to centralize administration and establish an Enterprise Hub despite running the College on a deficit. The Goldsmiths Recovery Programme was only unveiled after SMT secured a £7 million revolving cash credit in loans from Lloyds Bank and Nat West, which, in refinancing the College’s standing debt, made budget cuts a contractual requirement. Worth £60 million, the entire Goldsmiths campus save its main “Richard Hoggart” building were taken as collateral should the College breach its covenants.

To secure its deals with the banks, Goldsmiths was required to undergo an “Independent Business Review,” or an external audit, to identify savings opportunities. KPMG subsequently won a tender for the audit even though the chair of the Goldsmiths Finance & Resources Committee had worked for the firm for thirty-four years, presenting what the worker-led “Goldsmiths Collective Change Working Group” claim to be a clear conflict of interests.12 Releasing its findings to the College in September 2020, KPMG recommended measures previously proposed by GUCU as savings alternatives to Evolving Goldsmiths, such as selling excess campus real estate and halting capital expenditure projects like the Enterprise Hub. According to GUCU’s reports of the (embargoed) audit, staff redundancies were not initially proposed by KMPG. However, SMT contracted the firm again for an additional audit, this time to carry out a “Professional Services Blueprint” and an “Academic Portfolio Review” in which the savings recommendations shifted entirely to staff cost reductions and the financial profiling of modules and programs within departments. Plans for the Enterprise Hub were paused.

With contradictions abound in the recovery plan, GUCU members have illustrated how questionable financial framing by SMT alone casts the necessity of such a drastic restructure in dubious light. For one, the deficit reported by SMT as catastrophic is far lower than projections of as much as £25–40 million at the onset of the pandemic due to student enrolment holding despite state-issued travel restrictions. Meanwhile the underlying deficit of £6.5 million was reduced from £12 million in the previous year13 due to departmental savings through measures such as frozen pay rates and unfilled job vacancies. This means that savings have already come at the increase of staff workloads for stagnated compensation. In interviews conducted for this text, academic workers repeatedly stressed concern over the absence of an impact assessment of a further-reduced workforce. It’s argued that consequently further-swollen workloads and worsened staff-to-student ratios would adversely affect ability in the College to retain student numbers regardless of management’s insistence on growth, thus enabling SMT to repeatedly declare financial crisis. Nonetheless, the rejection of savings alternatives and the rehiring of KPMG to explicitly focus on reviewing staff-related expenditure— which accounts for the highest proportion of outgoing costs at 65%14— indicates that redundancies were always an intentional and essential feature of the restructure. In GUCU analyses, KPMG were consulted until SMT got the right answer, proving that the Recovery Programme is not one motivated by financial necessity but is of an ideological imperative and one by which the College has been intentionally nestled into the grip of the banks to shield the restructure from trade-union opposition.

* * *

Totaling thirty-eight strike days between November 2021 and March 2022, GUCU action against the Recovery Programme continues to demonstrate strengths in solidarity despite SMT’s pitting of workers against one another via metrics evaluation and students against workers more directly. For instance, in one of numerous emails to students throughout the year, Corner announced that she had taken the “unprecedented step of urging UCU members to not vote in favour of taking industrial action, given the significant effect any such action could have on our students’ learning and experience.” In the same message, the Warden linked an anti-strike motion from the University College London Students’ Union in spite of declarations of support of industrial action by the Goldsmiths SU. Student solidarity has, however, been clear in their presence on picket lines, in their disseminations of agitprop and zines, and in direct action—showing continuity from previous student support for workers’ rights at the institution, such as 2019 campaigns to end the outsourcing of cleaning and security staff. During a strike week in February 2022, students disrupted and momentarily shut down a Goldsmiths Council and Academic Board meeting, at which SMT was present, at the University of London campus in Central London. In a speech calling out misrepresentations of the College’s economic state, it was pronounced that “staff and students have been gaslighted by all this deception and dishonesty.”

Repeated email appeals from management to staff to cancel strike action in consideration of student welfare begs for particular attention, for the post-Browne Review university is itself premised on accumulations of wealth at the expense of students and therefore on the very contraction of welfare. GUCU reports that SMT have refused requests from academic staff that wages withheld during strike periods be redistributed to students as a refund for the significant teaching time lost in the past academic year,15 while students engaged in a fees strike in solidarity with staff have risked potential and actual expulsion from the College. (The first expulsion was issued to an international MA student on February 24th, mere days after the disrupted board meeting.) Concern for welfare, it seems, is extended only so long as students remain compliant in their positions along the capital flows of the institution. As such, claims that a restructure of Goldsmiths is motivated by desires to meet demands for improved “experience” at the university depends on a purely figurative student, simply referred to in mass emails, and one that stands in disregard of the fleshed demands of those on picket lines against staff cuts and curriculum changes.

Worker solidarity is not, however, organic to the institution but has grown from organizing pursued at various levels. The development of the anti-casualization movement in the College in particular goes some way to explain how such sustained strike action has been achieved against the Recovery Programme as well as how and why it’s been adopted as strategy at all. In the summer term of 2020, 472 associate lecturers, many of whom were also doctoral students of the College, faced contract termination ahead of uncertain enrolment projections in the new academic year as a result of travel and in-person teaching restrictions. Although accounting for 39% of departmental teaching labor for 7% of the pay, cuts to associate posts posed an easy savings opportunity for the College and one that could be accomplished by simply allowing fixed-term contracts to expire. To resist this, in June 2020 a number of associate lecturers embarked on a wildcat grading strike modeled off the UCSC strike of the same term. Their demand to management was relatively simple: for their contracts to be furloughed through October to allow actual, rather than projected, enrolment figures confirm the teaching demand before allowing contract expirations.16 While the strike ended after one month amid tensions with academic department heads, it revealed how those of the most precarious working positions have lead the way in regards to increased militancy among worker organizers. It also set a precedent for a January 2021 GUCU grading boycott as ASOS to demand no compulsory redundancies for two years—an action that also won a commitment from management that departmental budgets for associate lecturer pay would not fall below 95% of their 2021 level before spring 2022.

The wildcat strike furthermore provided an incentive for casualized workers, including doctoral researchers teaching on a fixed-term basis, to take up GUCU leadership positions to strengthen the branch’s anti-casualization stance.17 Subsequent strategizing against the Recovery Programme has thus been informed by increased consciousness within the union branch that precarious academic work can no longer be seen as a mere rite of passage to be endured as an early career researcher—if it should have ever been accepted as such—before the eventual attainment of long-term, so-called permanent work. Rather, the experience of wage insecurity, even perpetually so, is a de facto expectation for most entering graduate study to pursue academic work, and perhaps especially for those within the arts and humanities. Steered by workers employed on fixed-term contracts and others, it bears repeating, who’ve been directly targeted by SMT for redundancies, the GUCU response has been formed in recognition that the Recovery Programme represents, at bottom, an ongoing disintegration of tenure and entrenchment of casualization for all except those of managerial posts.

* * *

In a recent panel discussion, Claire Fontaine expanded on their notion of a “human strike” as “the disarticulation of the mechanisms that make everything functional and make everyone complicit in the processes that continue to destroy what is alive and healthy. It is a defunctionalization of struggle itself as a tool for reform, it’s the immanence of self-transformation through the refusal of oppressive dynamics.”18 While Claire Fontaine’s human strike is not restricted to workplace or university struggles, it is such a space for disarticulation, defunctionalization, and refusal that seems possible through the strike and boycott of Goldsmiths: by staging an utter rejection of the ideological agenda imposed not just by current management but general management patterns of academia, the institutional violence already manifest through the histories of the university, and the precarity into which workers across the institution are interpellated. Disrupting the ways in which the College functions, the withdrawal of labor strikes at the institution as capitalist enterprise and transforms the positions from which subjects interact—be they (co)workers or students—to more than variables on a metrics scale representing incoming capital or outgoing costs.

Despite this positive reading of the strike—genuinely expressed from the position that organizing at Goldsmiths has set an important bar in the sector—limitations remain inherent to its form. With restructures like the Goldsmiths Recovery Programme but a symptom of a wider political and economic context, the local strike can only serve as a temporary tactic in an ongoing struggle, while organizing across the terrains of higher education must engage beyond institutional parameters. This, too, reveals potential limitations of the academic boycott in UCU’s current iteration. If applied with consideration of the risks of reputational damage, the boycott might be seen to operate according to and therefore uphold prestige based on the calculable merit of those attached to the institution. While the boycott of Goldsmiths articulates a rejection of the ideological drives of marketization, it seems necessary that its conceptualization, at local or general level, be extended to somehow encapsulate worker orientations towards the academy, specifically default identifications as an academic before an institutional worker,19 that enable elevations of concern for reputation, academic clout, or prestige above working conditions and the liveability of life bound to the university. How will the institution operate when the lines of reverence are completely redrawn?

As drops in recruitment and retention numbers and measurements of student satisfaction (as recorded by the National Student Survey) are instrumentalized to discipline and dismiss workers at universities, it seems likely that a concerted student movement will be required to sustain labor disputes at Goldsmiths (and indeed elsewhere) beyond the current academic year. This too will require maintained awareness of the parallels between students and staff in the political economy of the university—or put frankly, the ways in which the exploitation of each is related to the other. While the indebtedness of students as “cash cows” has been a point of focus in the Goldsmiths fees strike as well as rent strikes organized at several UK universities during COVID-19 lockdowns, we are far off a student-led movement against the financialization of education to match that of 2010 which saw fifty-thousand take to the streets of London. Twelve years ago, students were galvanized by that which was being diminished: the guarantee of affordable public higher education. Students today must now reckon with that which has never been offered. Their determination to transcend assigned positions as financial nodes through the university may, in the end, determine the outcomes of the labor movement to come and the university to follow. It’s perhaps from such collective desire that a new political subjectivity will emerge, which Fisher saw as a necessary occurrence to subvert resignations toward managerialist education.20

With sincere thanks to the workers and students at Goldsmiths who shared insights for this text.

References

| ↑1 | Originally from Capitalist Realism: Is there No Alternative? (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009), 17. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Perhaps it’s worth saying that the savings measures of the restructure have not been extended to the reduction of senior management salaries to prevent redundancies elsewhere. The salary for the Goldsmiths Warden in 2021 was reported as £245,000 including taxable benefits —a sum noted in the College’s official financial statement for 2020-21 as more than six times the median total remuneration of staff. See “Annual Reports and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 July 2021,” 53, <“https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/docs/public-information/annual-reports/financial-statements-2020-21.pdf> [Accessed March 30, 2022]. |

| ↑3 | See “Censure and Academic Boycott Policy,” <https://www.leedsucu.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/UCUHE56_Censure_and_Academic_Boycott_Policy.pdf> [Accessed March 30, 2022]. Academic boycotts are becoming more frequently deployed in the UK, as the UCU branch of Queen Mary, University of London, similarly called for one in February 2022 over punitive salary deductions from staff for actions short of strike. There was also a boycott of the University of Leicester in another redundancies dispute in spring 2021. UCU does not encourage current or prospective students to boycott sanctioned institutions. |

| ↑4 | Robert Anderson, “University fees in historical perspective,” History and Policy, February 8, 2016,<https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/university-fees-in-historical-perspective> [Accessed March 27, 2020]. |

| ↑5 | See Andrew McGettigan, The Great University Gamble: Money, Markets and the Future of Higher Education (London: Pluto Press, 2013), 1. |

| ↑6 | International students pose a particularly lucrative market for UK universities—paying up to three times the amount as home-rated students—and accounted for 34% of total fees income at Goldsmiths in 2020. |

| ↑7 | Fleming, Dark Academia: How Universities Die (London: Pluto Press, 2021), 39. Wendy Brown has a similar discussion regarding US higher education; see Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (New York: Zone Books, 2015), 176-90. |

| ↑8 | The withdrawal of subsidies were intended to reduce government spending on public education and make way for private college competitors in the sector, while, to compensate for rising individual costs, government loans were introduced to at least partially cover fees and living maintenance for students at public and private institutions. This created a repayment-scheme state asset, with tranches of privatized debt loans subsequently sold to the private sector to reduce public deficits. <https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01079/> [Accessed 27 March, 2022]. However, while block grants were £5 billion annually in 2010, the government now issues around £20 billion in loans to 1.5 million students each year, with an outstanding state-held debt at £141 billion in March 2021. The average debt among individual borrowers in 2020 was £45,000 <https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01079/> [Accessed 27 March, 2022]. Those with student debt in the UK do not begin making loan repayments until their income exceeds various thresholds, and undergraduate loan repayments are set at 9% of pre-tax income. Therefore, paradoxically, while the state curtails direct funding of universities, it carries increasingly vast amounts of student debt. Until 2022, the outstanding balance on student loans was to be written off after a thirty-year period. <https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicsectorfinance/methodologies/studentloansinthepublicsectorfinancesamethodologicalguide> [Accessed 27 March, 2022]. Government policy changed in 2022, extending the repayment period from thirty years to forty. By this alteration, Grace Blakely reports in Tribune, a projected 70% of graduates would repay their student loan in full, up from 20% in the thirty-year period projection; see https://tribunemag.co.uk/2022/04/student-loans-finance-graduates-cost-of-living-crisis-inflation-conservatives [Accessed April 21, 2022]. |

| ↑9 | Fleming, 13. |

| ↑10 | See also “An Alternative Approach to Evolving Goldsmiths: Doing Higher Education Our Way,” March 17, 2020. <https://goldsmithsucu.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Alternative-Goldsmiths.pdf> [Accessed 27 March, 2022]. |

| ↑11 | Unlike the Goldsmiths Recovery Programme, references to “Evolving Goldsmiths” are not visible on the College website. Webpages hyperlinked in this text may be edited or deleted by management. |

| ↑12 | KPMG has since been the subject of several scandals relating to negligence in auditing procedures and gross misrepresentations of the financial outlooks of contracting corporations; see https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/feb/03/kpmg-being-sued-for-13bn-over-carillion-audit-uk-official-receiver [Accessed April 1, 2022]. |

| ↑13 | See “Annual Reports and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 July 2021,” 18. |

| ↑14 | In 2021, the College reported total outgoing staff costs as £91.8 million, just £3.4 million less than reported total fees and education contracts income for that year <https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/docs/public-information/annual-reports/financial-statements-2020-21.pdf> [Accessed March 27, 2022]. In 2020, staff costs before a sizable private pensions credit issued to the College was reported at £95.5 million, while total fees and education contracts income was reported at £100.2 million <https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/docs/public-information/annual-reports/financial-statements-2019-20.pdf> [Accessed March 27, 2022]. To the management of an institution prioritizing economic growth above all else, outgoing expenditure that comes close to the amount of the primary source of income, student fees, seems not the last nor regrettable but the logically first and obvious choice among budgetary “savings opportunities.” |

| ↑15 | See “GUCU Response to the Warden’s Most Recent Communications,” https://goldsmithsucu.org/2022/03/17/gucu-response-to-the-wardens-recent-communications/ [Accessed 29 March, 2022]. |

| ↑16 | In a recording for Montez Press Radio, associate lecturers who organized and partook in the Goldsmiths wildcat strike provide an excellent breakdown of the complexities of organizing across the institution < https://soundcloud.com/scourti-studio/goldsmiths-wildcats-in-conversation> [Accessed 29 March, 2022]. |

| ↑17 | Meanwhile, lecturers hired by the College as independent contractors for public-facing short courses won a legal case against the College in October 2021, gaining worker status and previously denied union representation and paid leave. This presented a concrete success for the labor struggles at Goldsmiths as well as for the anti-casualization movement across the sector. Short-course lecturers at Goldsmiths were represented in their case by the same firm that in earlier 2021 represented a UK Uber drivers’ campaign for workers’ rights< https://www.leighday.co.uk/latest-updates/news/2021-news/university-lecturers-win-their-claim-for-worker-status-against-goldsmiths-university-of-london/> [Accessed 29 March, 2022]. |

| ↑18 | Claire Fontaine, Iman Ganji, and Jose Rosales, “Foreigners Everywhere”, Diversity of Aesthetics, Volume II, edited by Andreas Petrossiants and Jose Rosales (New York: Emily Harvey Foundation, 2022), 13. Emphasis in original. |

| ↑19 | As Roberto Mozzachiodi outlines, quoted in “Our Consciousness and Theirs,” https://viewpointmag.com/2022/01/18/our-consciousness-and-theirs-further-thoughts-on-the-class-character-of-university-worker-activism/. |

| ↑20 | Fisher, 53. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine