How should we evaluate the strength and composition of the left-wing opposition in Bolsonaro’s Brazil? Not even a year into the Bolsonaro experience, it is still early to try to map the country’s varied fronts of resistance. But what follows provides at least some initial elements, touching on education, political scandal, the labor movement, feminist and black liberation fronts, state repression, tactical and strategic debates on the Left, the overweening legacy of the PT, and the meaning of fires in the Amazon.

Out of the Classroom and Into the Streets

Shortly after I arrived in São Paulo in early April, I met a friend at a subway station in the middle-class neighborhood of Pinheiros. It was 9:00 a.m. on a Sunday and we were en route to the city center for a leadership meeting of the São Paulo state chapter of Rede Emancipa (Emancipation Network), a popular education movement that offers free classes to working-class and poor students, as well as prison inmates. Young women and Afro-Brazilians led the discussion when we arrived – a good indicator of movement health, my friend stressed.

The classes are oriented around preparation for the practical necessity of passing standardized tests which mediate entry into the university system, or access to education credits for inmates who hope to reduce their time in prison. But from those immediate bases, the volunteer teachers also encourage students to analyze the racialized class nature of the education and prison systems themselves, and more broadly to interrogate the underlying injustices of Brazilian society. In a certain sense, these activists hope to make the fantasm of “cultural Marxism” that extreme-right president Jair Bolsonaro claims pervades the educational structure as close to a reality as possible.

Education wasn’t a random point of entry into the contemporary Brazilian predicament. It has become one of the pivotal terrains of conflict in the first eight months of Bolsonaro’s rule, heating up especially since Bolsonaro’s threats to defund sociology and philosophy university departments, followed by plans to radically cut funding to public universities and research bodies, as well as to basic education. The Ministry of Education has approved 70 percent more private universities in the opening months of 2019 than it did in the entirety of last year, conceding ground to the private education lobby, headed by Elizabeth Guedes, sister of Paulo Guedes, the finance minister and neoliberal sage of the Bolsonaro government. But, as the Brazilian philosopher Rodrigo Nunes suggests, this assault on education is difficult to reconcile with public sentiment. The social roots of education in the country run deep, with many poor families seeing higher education through public universities as the only possible path to social mobility.

On May 15, crowds of people descended onto the streets of the country’s state capitals and 200 secondary cities in the largest display of public hostility to the regime since Bolsonaro’s inauguration on January 1 this year, and by some accounts the biggest demonstrations in the country since June 2013. Momentum continued two weeks later with repeat demonstrations shaking the country on May 30. “In the capital, Brasília,” a Guardian correspondent reports, “student protesters were filmed burning an effigy of the Brazilian president while chanting the increasingly common refrain of his opponents: ‘Hey, Bolsonaro go and get fucked.’” These were the first signs of life for coordinated popular resistance to the government. On June 14, on the back of the May successes, the resistance to Bolsonaro pulled off the first general strike against the regime.

On the same Sunday as the Emancipation Network gathering, on Paulista Avenue, the main thoroughfare in São Paulo and point of convergence for most large demonstrations in the city, there were mobilizations of the right and left, commemorating or commiserating one year since former president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party (PT), was incarcerated on trumped-up corruption charges. The meekness of the left and the bravado of the Bolsonaristas in the early days of the new management in the Planalto, as the presidential palace is known, was captured in the front cover image of the next day’s edition of Brazil’s leading liberal newspaper, Folha de São Paulo. Three well-dressed men, Bolsonaro supporters, probably in their late 50s, are strangling, manhandling, and yelling at a young female, probably in her twenties, an advocate for Lula’s freedom.

The Law

An anonymous source recently provided investigative journalists at The Intercept with a treasure trove of “private chats, audio recordings, videos, photos, court proceedings, and other documentation” which reveal “highly controversial, politicized, and legally dubious internal discussions and secret actions by the Operation Car Wash anti-corruption task force of prosecutors, led by the chief prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, along with then-judge Sergio Moro.”1 The Intercept unleashed its first flurry of reports in early June, with many more apparently in the pipeline based on an archive of materials now in their possession (and also safely secured outside Brazil, should the government intervene). The investigative reports published thus far indicate unambiguously that the Car Wash prosecutors were fundamentally motivated by the desire to prevent the PT’s return to power, and that Moro secretly collaborated with them on various fronts to ensure this outcome, even while presenting himself as a neutral arbiter of justice. This was long suspected by PT supporters and critics of the Bolsonaro government, but hard proof had been lacking until now.

The significance of The Intercept findings is already clear as day, even if there are still many more stories to be published. Moro convicted Lula after clandestinely and illegally collaborating with the prosecutorial team at a time when Lula was leading in the polls of the 2018 presidential race by a wide margin. Only after Lula’s conviction and the PT’s switch to Fernando Haddad as candidate did Bolsonaro’s numbers begin to rise. Without Moro’s actions it is far from obvious that Bolsonaro would ever have been elected.

Lula’s Old Stomping Ground

In mid-April I drove with 36-year-old Eduardo Portelo from São Paulo to the suburb of São Bernardo. Our destination was the headquarters of the metal workers’ union, perhaps the single most emblematic site of modern class struggle in Brazil, and the place where Lula got his start in the labor movement. When facing arrest a little over a year ago, it was in the metal workers’ headquarters that Lula sought refuge, with tens of thousands of PT supporters and activists further to the left gathering to contest his imprisonment.

Eduardo started his political activism at the University of São Paulo, where he was enrolled in a Social Sciences degree. He became heavily involved in the student movement. At the time, he was close to a faction of the PT called Socialist Force, which in 2005 split off to help form the far-left, multi-tendency Party of Socialism and Freedom (PSOL). Eduardo decided to stay in the PT “to fight for the character of the party, and to try to make it a political instrument for changing the living conditions of the working class.” After his undergraduate degree, he became an advisor to the PT-led metalworkers’ union, working closely with their secretary for international relations as well as their secretary for youth. The metal workers’ union forms part of the Central Labor Federation (CUT), the most docile of the national labor federations, and seen by many on the Brazilian left as having abandoned any serious commitment to organization and mobilization during the bulk of the PT era.2

A loyalist, Eduardo nonetheless was keenly aware of the limits of independent union struggles during the years of Lula, and his successor Dilma Rousseff. “There was a mantra within the leadership of the PT,” he explained to me, “that when it got into government it needed to maintain three footholds in different spheres. The first is the government, the second is the social movements, and the third is the party itself. So the party must have qualified activists and qualified political leadership in each of these three domains. With the election of Lula in 2002, all of the qualified personnel that we had immediately went into the federal government. The foothold that the PT had in the social movements and in the party itself was weakened, because everyone began working for the government – people who had been longtime activists in social movements, union organizers. We weren’t able to produce new leaderships to occupy these spaces, so we lost some of our proximity with the rank and file in the unions, on the shop floor, and so on. This was one of the biggest problems.” There was, then, a simultaneous process of professionalization and bureaucratization of movement leaders and a decomposition of rank-and-file density.

Still, the Brazilian labor movement, in comparative terms, retains considerable power. Despite the limits of the CUT and the informalization of the world of work in recent years in Brazil, there has been considerable labor unrest. In 2013, for example, there were a record-breaking 2,050 strikes, and the third-highest number of hours lost to industrial action in the country’s history. In 2016, there were 2,093 strikes, with 1,100 in the public sector and 986 in the private sphere. This number fell to 1,566 strikes in 2017, which is still a decent number, even if qualitatively these actions were characterized by an overwhelmingly defensive character in the context of economic crisis and government austerity.

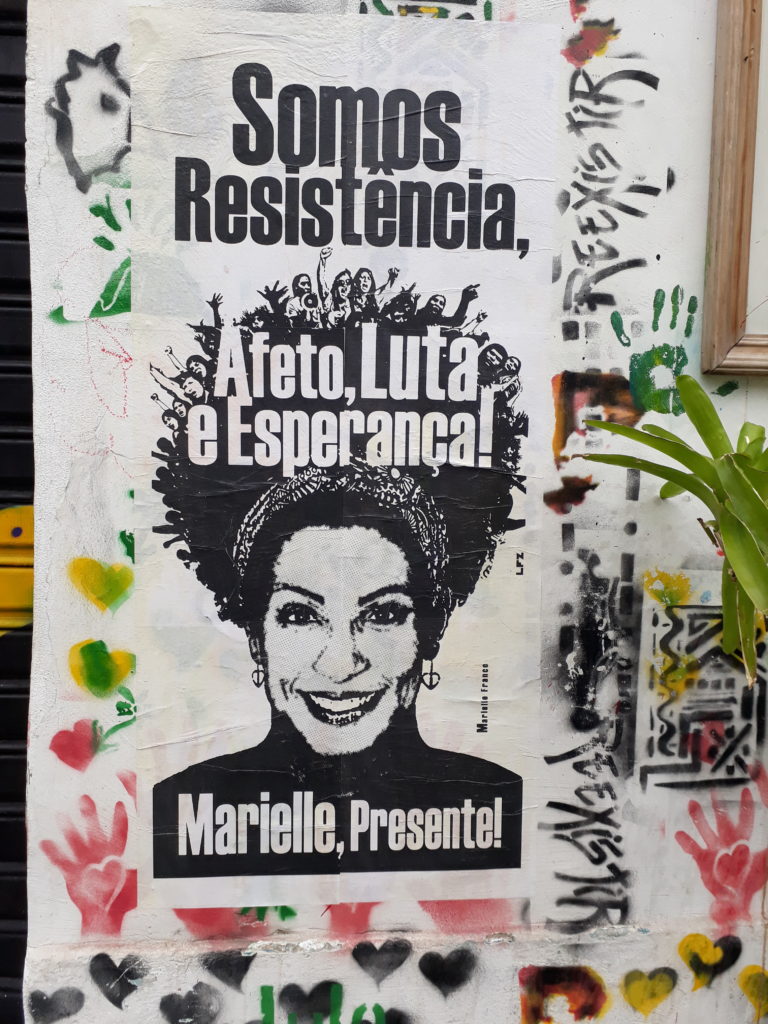

On the day of my visit, the interior of the metal workers’ headquarters was festooned with banners calling for Lula’s freedom and commemorating the martyrdom of Marielle Franco, a 38-year-old PSOL councilperson in Rio de Janeiro, and prominent local activist in black, feminist, and LGBTQ+ struggles, who was shot and killed in a premeditated, professional assassination in the center of Rio a little over a year earlier. It was the day of a national meeting of metal workers in which plans were being concretized for May Day events as a precursor to an expected general strike sometime in June.

I sat in on the proceedings and was introduced to the delegates as an international researcher. I interviewed Paulo Cayres, president of the National Confederation of Metal Workers, but it was difficult to extract more than formulaic slogans, consisting of a combination of militant expectations for the general strike in June, denunciations of Bolsonaro as fascist, and nostalgic reminiscences of the PT era. In the metal workers’ canteen over lunch, virtually everyone at the large table I ate at was more circumspect about whether the strike would be general in anything but name, more detailed in their analyses of the reigning balance of forces, and more worried that the logistically critical truck drivers would be bought off by the Bolsonaro administration as they had been in the recent past.

Eduardo shared the skepticism of the canteen: “The left is not in a position to organize an effective shutdown of the whole country. What we can do is create huge demonstrations. Huge demonstrations that last for one day, and that’s it. They don’t cause any substantial damage to capitalists.” Still, he saw a possibility, as did many others, in the cohesive potential of a war over pensions. “The most important struggle at the moment is the one around pension reform. This has a possibility of generalizing in an effective way, because so many people are going to be affected. The main axis in which the opposition is organizing right now is around the pension reform.” Even here, though, Eduardo noted that it wasn’t the left that had so far delayed the government’s progress on this front: “Still the best chance of the pension reform falling apart is not because of the strength of the movements, but because of the incompetence thus far of the Bolsonaro administration.” Unfortunately, it now looks as though the pension bill will pass successfully through Congress.

Untested Terrain

A conversation on April 11 with Jane Barros provided a broader panorama of struggles beyond the labor movement. Jane, a 39-year-old Afro-Brazilian woman, was raised in the suburbs of São Paulo by parents who were activists within the PT. Her father was also a militant in the metal workers’ union. She became politically active around 15 or 16 years of age in election campaigns, the labor movement, and neighborhood issues. Jane eventually departed the PT and was one of the founding members of PSOL. A sociologist by training, she taught at universities in Rio for 8 years, where she organized within the Front for the Legalization of Abortion and taught popular education classes in the Florestan Fernandes educational program of the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST), before returning to São Paulo.

Jane spoke of the weakness and fragmentation of popular movements in the first three months of the Bolsonaro administration, beginning with the conflict over pensions. While popular sentiment is pitted against the reform, this hasn’t translated into a solid campaign of any kind: “one of the central questions is to organize resistance to the project of pension reform being advanced by this government. There is a sense of unity against this across the different labor confederations and fronts of social movements. But there is no capacity for organizing material actions. There was a national assembly around this recently in the center of São Paulo, and it was very small. Around the pension reforms, we should also be clear that the polls show that people don’t want the reform. And the government understands that it is unpopular. But there is little struggle in the streets or in the labor movement around this, not least because of the bureaucratization of the latter. It is not inclined toward mobilization and confrontation.”

At the same time, Jane pointed to areas of potential conflict and social explosion, particularly around gender and racial oppression. “The demonstrations on March 8, Women’s Day, were very big. The movements and actions against state repression and the impunity of the killers of Marielle Franco have also been important. These are actions that have mobilized many people, which have involved more organized movements and more spontaneous explosions. These are spaces to which we have to devote more attention, because struggles could explode around these themes.” Anticipating the mass protests that would emerge a month after our conversation, Jane observed that “the government is also attacking education very fiercely, in its campaign against the supposed presence of ‘cultural Marxism.’ So struggles could also erupt in this area.”

Feminist Fronts

Even the most casual observer of Latin American politics over the last few years would be hard-pressed to miss the emergence of a new wave of feminist militancy. In Brazil, one particularly potent expression of the new movement was the extraordinary #EleNão (#NotHim) protests that erupted between the first and second rounds of the October 2018 presidential elections. Hundreds of thousands of women mobilized behind this slogan in an effort to prevent Bolsonaro from taking up the presidency. While obviously falling short of that specific goal, Jane pointed to the residual afterlife of those experiences in the streets. “There is a discussion right now of whether we are living through a new feminist wave. For me, it’s a feminist wave characterized by responses from the most vulnerable sectors of society, which are feeling the bite of austerity, of the crisis, most strongly, and are responding to this. During #EleNão I was part of a women’s collective, and during those demonstrations my comrades and I thought that we had the capacity to prevent Bolsonaro coming to power. They were massive mobilizations, involving organized and spontaneous sectors of society. There was a widespread sensation that we could stop Bolsonaro. There were around 500,000 of us, mostly women, in São Paulo. But we hadn’t counted on the power of the churches, of the evangelicals. With their support, Bolsonaro’s power actually increased.”

And yet, as is so often the case, even out of failure the movement experience has left a trace. “I don’t think this movement has disappeared,” Jane said. “The fact that March 8 was big is one indication of this. There is a part of the movement that is arguing for more unity and more organization of the movement. For example, I recently participated in a meeting in São Paulo which is part of a wider global initiative to build a feminist international – following on the heels of the manifesto written by Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser.3 In 18 years of being involved in the women’s movement, I had never seen a meeting of women in which there were women from the PT, independent women, women from the autonomist movement, women from PSOL, and so on, all of them thinking together how to advance this initiative. So there is the basis here for something interesting. There are many, many small collectives that exist and now there is an initiative by the most organized sectors of the women’s movement to cohere behind this initiative in Brazil. It’s an interesting moment. We are arming ourselves for coming battles.”

Bolsonaro’s unfettered attacks on “gender ideology” recall Wilhelm Reich’s insight that patriarchal relations and the authoritarian family are the root of the state’s authoritarian power in capitalist society. The president’s theatrical displays of misogyny – he once told PT congressperson Maria do Rosário that she wasn’t worth raping – have granted wholesale permission to unleash the worst strains of gendered violence already present in the interstices of Brazilian society. “Rape is as common as murder in Brazil,” Perry Anderson reported recently in the London Review of Books, “more than sixty thousand a year, around 175 a day – the number reported has doubled in the last five years.” Queer Brazilians have likewise been subject to unmitigated savagery. Already facing the highest level of lethal violence against queer people in the world, with 455 reported murders in 2017, the presidential election race of 2018 witnessed roughly 50 attacks by Bolsonaro supporters, including two trans women who were killed by men who expressly carried out the murders in Bolsonaro’s name.

State Murder

If popular movements are figuratively arming themselves for forthcoming battles with Bolsonaro, the state and its para-state allies have been going about things more literally. Repression remains one of the most serious impediments to movement organizing in the country.

According to the Brazilian Annual Public Security Report, in 2017, Brazilian police forces killed 14 people per day, 5,144 over the course of the year – a 20 percent increase relative to 2016. In 2017, 367 police officers were killed, an average of one per day. The uptick in police repression had no demonstrable effect on its purported aim, the reduction of homicides, of which there were 63,880 that year, 3 percent more than in 2016. The military, military police, and militia composed of ex-officers, firefighters, and security guards, often correspond in their aims and actions. In 2018, with Rio de Janeiro’s favelas under military intervention at the behest of then-president Michel Temer, there were 1,532 officially registered killings by police. In 2019, the numbers have been equally impressive: 170 dead in January alone. After the apparent execution of 15 young men by police after they had been detained, Wilson Witzel, governor of the state of Rio, immediately declared the police actions to have been legitimate.

I asked Jane about how things have changed with the ascension to power of Bolsonaro on this front: “The situation is much worse. This is a government, as I’ve suggested, with all the characteristics of the extreme right and which includes within it military forces. The amplification of the coercive wing of the state apparatus is a central feature of this government’s strategy – a politics of extermination against certain sectors of society. You can feel it on an everyday level, as a black woman. I sense everywhere I go a much more aggressive environment. Just the other day, an elderly white man started yelling racial abuse at me. Nothing like that had ever happened to me before. It was a little thing, but it’s more the question of a sensation in the streets, a feeling at the everyday level that there is a higher intensity of oppression, in the discourse, and so on.”

The PT Axis

In a dialogue with Juan Grigera and myself in December last year, Rodrigo Nunes suggested that “the PT is a waning hegemon” on the Brazilian left, but “a hegemon nonetheless; its organizational social base and electoral clout, while dwindling, remain substantial. Haddad’s electoral performance perfectly illustrates the impasse: being Lula’s candidate is enough to get you to the run-offs, but carries so much rejection that you’re almost guaranteed to lose.” The polarization around the PT, however, should be understood dialectically: “another force keeping the PT in place is the hatred against it: the sheer rabidity of antipetismo helps keep petismo alive. Dilma Rousseff’s second term would probably have discredited the party definitively; her impeachment and Lula’s imprisonment regalvanized the PT’s base and made many people more willing to disregard its myriad faults.”

An overarching anti-petismo/petismo polarity has sharpened in Brazilian society, which is at once a trap and a gravitational force impossible to ignore for the independent left. For Rodrigo, this dynamic has “tied the hands of the left, as now it has been forced to square the circle of being critical of the PT and critical of antipetismo, anti-systemic but against the attacks on the system coming from the right, and so forth. This is a position all but impossible within the given coordinates, especially when you have nowhere near the same resources that other actors can mobilize, and when the war on the PT is a step in a war on the left as a whole. Yet it’s clear that the left can only cut this Gordian knot by escaping the petismo/antipetismo polarity; for as long as we stay within it, we’ll be exactly where our adversaries want us to be. Tellingly, the most successful mobilizations since 2016 (high school occupations, feminist demonstrations, the lorry drivers’ strike) were diagonal to that opposition. In contrast, when the PT tried to put their stamp on the movement against Temer’s reforms, they killed it.”

The tenacity of the PT’s gravitational pull on other movements and the fragmented independent left can be seen in the singularity of the focus of the “Free Lula” campaign over the course of the first several months of Bolsonaro’s rule. The experience of that pull as a Gordian Knot, in Rodrigo’s terms, was also sharply noted in a conversation I had in mid-April with Paula Silva, a 32-year-old Afro-Brazilian activist who played a leading role in the autonomist circles of Movimento Passe Livre (Free Pass Movement, MPL) within the June 2013 uprisings against spikes in public transport tariffs.4 She lamented the way in which critical sectional struggles today are consistently drawn into the sphere of the PT via the all-encompassing Free Lula framing.

“Today,” according to Paula, “if we have a march it will inevitably be under the banner of Free Lula. If we have a march around justice for Marielle Franco, it ends under the banner of Free Lula. If we have a march around public transport, it’s done under the banner of Free Lula. This has engulfed all social movements, and has diminished their demands, rather than advancing them.” All of this is taking place in a context of Bolsonaro’s heightening assault on movement spaces: “There is an institutional politics, a macro-political framework, under Bolsonaro which is trying to fragment the most organized and rooted popular movements. There is a persecution of movements. There is a persecution of traditional movements, such as the Afro-Brazilian and indigenous struggles, there is a criminalization of struggles in the city, struggles in the streets. There is a strengthening of the repressive forces.” Paula emphasizes the degree to which social movements are still learning to navigate the new terrain: “I don’t think we have had enough time yet to reorganize our forms of struggle, or develop our understanding of the new political scenario. But it’s also true that repression didn’t just begin now. It began in 2014, under the PT, under Dilma.”

Strategies for Exit

The new scenario introduces novel complexities to the question of strategy. Jane points to three elements of the problem of unity facing left oppositions in the present moment. The first issue is one of left unity and class struggle around immediate defensive battles, “a united front of all movements and parties that are progressive and on the left that want to confront the most regressive initiatives being undertaken by this government – the pensions, the attacks on women, the attacks on education, things like that, which bring together a sense of social class. If we can do this in a united way it will enable the strengthening of the movements and their efforts to confront the government.”

The second sense of unity is broader, “we can think of democratic fronts, with everyone who wants to defend democracy. For example, in the struggle to defend the right to association, the right to a free press, there are going to be liberals who are alongside us. We will unite on this level to confront the right.”

Finally, Jane sees a third strategic emphasis, stretching out over the longer term, of rebuilding an anti-capitalist project of counter-power. At this level, “there is the necessity of reorganizing the left. We need to build the possibility of constructing an alternative pole of power, another kind of power, a project of anti-capitalist power. There is really no exit to the current situation thinking only in terms of the first two levels I’ve mentioned, without thinking through this last question – which is very difficult, which has to involve many different movements and parties. But we have to think through the organization of an alternative of power.”

War of Position

In a controversial recent piece in Esquerda Online, Valerio Arcary – once a leading figure in the Unified Workers’ Socialist Party (PSTU), a Trotskyist grouping, and now a member of PSOL – warns that the Brazilian left needs to avoid two prevalent tendencies in the current conjuncture.

On the one hand, there are those on the left who consider the present an offensive moment, and thus call for the immediate fall of the Bolsonaro regime through mass mobilization, general strikes, and impeachment proceedings in parliament. For Arcary, this voluntarist view misapprehends the actual balance of socio-political forces in the country, and when mobilizations are insufficiently powerful to bring down the president, the temptation is to turn to substitutionist shortcuts, like congressional calculus, in the vain hope that Bolsonaro will be impeached in that venue. Arcary suggests that the success of building the education mobilizations, the biggest resistance endeavors thus far under Bolsonaro, was rooted in their immediate orientation around defending public education. These kinds of defensive actions, he argues, will with time build the accumulation of forces necessary to move to offensive struggles. But that patient accumulation of forces, that war of position, cannot be artificially willed into existence by pretending it has already arrived on the scene.

On the other hand, there are those who insist on the centrality of electoralism, and in building a broad centrist coalition in this domain, most immediately for the forthcoming municipal elections. From this point of view, the left needs to subordinate its distinctive politics in a broad electoral front capable of collecting all elements of society which are aligned in opposition to Bolsonaro.

Not wishing to be misunderstood, Arcarcy insists that multi-party and multi-movement unity in action is, to be sure, exactly what is necessary in struggles such as the one around Lula’s freedom. The danger, however, is moving to an electoralist romanticization of such unity in action. The left will not be strengthened by defending the ideas of the center in municipal electoral contests, or by moving its attention from extra-parliamentary terrains of conflict.

Both strategic tendencies, then, are incorrect. The left has not yet accumulated sufficient socio-political power to move to bring down Bolsonaro through a permanent offensive assault. This is premature. That moment will arrive, but in order for it to be successful a realistic assessment of the necessary groundwork still to be carried out is in order. At the same time, tailing any electoralist reconfiguration of the center would be deadly for the left.

For Arcarcy, because any frontal assault on Bolsonaro would still end in his victory given the reigning balance of forces, a longer-view war of position is called for, in which the maximal defensive struggles are pursued, taking advantage of each and every division, split, and error in the ruling bloc, to build the prospects for a counter-attack capable, eventually, of full, open confrontation. This is the road to building the kind of mass movement necessary to overthrow Bolsonaro.

Amazon in Flames

With the Brazilian Amazon now on fire for over a month, and Bolsonaro ailing in his response, momentum is building – indigenous defense for survival, mobilizations in the cities, and international solidarity campaigns – for another front in the defensive accumulation of forces. Time will tell if it ultimately tips the balance and opens up windows onto the offensive.

According to INPE, Brazil’s space agency, there have been more than 74,000 fire outbreaks in 2019, an increase of 84 percent relative to the same period last year. Relatedly, the same institution’s deforestation data under Bolsonaro’s rule points to cataclysmic catastrophe – between January and July satellite imaging has revealed 4,696 square kilometres of raised Amazon rainforest, nearly twice the rate of the same period last year. Annual deforestation of the Amazon in Brazil had slowed under Lula from 10,000 square miles per year in 2004 to under 2,000 in 2014, only to climb again under Dilma. Despite the relative slowdown of deforestation within the borders of Brazil under Lula, the PT’s alliance with agrarian capital was never contained within the parameters of the nation-state. Brazilian capital’s extended foray into neighboring countries – correctly identified as sub-imperialist by many on the Brazilian far left – was encouraged by Lula and Dilma through loans issued by the country’s massive development bank (BNDES), as well as the Brazilian-backed Initiative for the Integration of the Regional Infrastructure of South America (IIRSA), a key instrument in the intensification of extractive capitalism in the region – agro-industry, natural gas and oil extraction, and large-scale mining – during the commodities boom between 2003 and 2011. Any reasonable assessment of the PT’s impact on the Amazon would have be measured in these terms, as well as in its general role of endorsing and accelerating the soy and beef complexes internationally, within which Brazilian capital plays such a central role.

From the beginning, according to a recent piece by Daniel Aldana Cohen in Dissent, Bolsonaro’s plans have involved “pronouncing the Amazon open for business, pledging to reboot the construction of devastating megadams; neuter environmental police, who combat land grabbers and illegal miners; hack away at indigenous land reserves; and invite cattle barons to slash the forest’s rich canopy and graze their steers in the ashes.” For Cohen, if Bolsonaro is left unfettered, “blood will soak the Amazon. Already, the rising murders of indigenous activists – the Amazon’s great defenders – are an index of deforestation, and a testament to the frontier spirit of large segments of agro-industrial capital.”

Bolsonaro’s response to public outrage over the fires has been true to form. Ricardo Galvão, until recently a physicist at INPE, was fired and driven into exile in the wake of Bolsonaro’s condemnation of the agency’s data on deforestation. Before belatedly sending some troops to help fight the fires and placing a meager 60-day ban on fires in the Amazon, Bolsonaro had raged against “environmental psychoses” running wild on the left, and alleged that the uptick in fires was due to a vast pyromaniacal conspiracy organized by environmental NGOs to undermine his government.

Protected indigenous reserves have been favoured locales for intentional blazes set by loggers and land grabbers, stoked by Bolsonaro’s genocidal rhetoric on civilizing the indigenous population of the Brazilian Amazon. According to Dom Phillips in a recent report for the Guardian, “Antenor Vaz, a former employee at Brazil’s indigenous agency FUNAI and consultant on isolated indigenous peoples, said research based on NASA images showed that fires broke out in 131 indigenous reserves from 15-20 August. Of these, 15 were home to indigenous groups who are isolated or in stages of initial contact.”

The invasion of indigenous lands and the criminalization and repression of indigenous movements are long-standing in Brazilian history, but they have gathered particular momentum and ferocity under Bolsonaro. “The Waiãpi tribe recently reported invasion by prospectors and the assassination of Chief Emira Waiãpi” notes a recent editorial on the influential left-wing website Esquerda Online. “Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa said that because of illegal mining and gold miners themselves, the Yanomami have been drinking mercury-contaminated water, becoming ill and dying from malaria and a shortage of doctors and medicines… The genocide of the indigenous people is not new,” but the novel intensity of Bolsonaro’s actions must be resisted. “The actions being carried out in dozens of cities in defense of the Amazon are very important. If it is not us, the youth, the indigenous, the women, the workers, it will be nobody. Amazon, present!”

Carlos Walter Porto-Gonçalves, author of an important book published last year, Amazônia encruzilhada civilizatória: Tensões territorias em curso (The Amazon at a Civilizational Crossroads: Ongoing Territorial Tensions), noted recently that there have been more targeted assassinations in the Amazon of Brazil than any other region of the Brazilian countryside since 1985, the year this type of occurrence began to be registered by the Pastoral Land Commission. For Porto-Gonçalves, the recent resurgence of the Amazon to international consciousness is reminiscent of the late-1980s, captured most succinctly perhaps in Time magazine naming the region its personality of the year in 1988 – the same year one of the historic defenders of the Amazon, Chico Mendes (1944-1988) was assassinated.

Porto-Gonçalves points out that much of the fate of the Amazon is tied to the policy of capitalist states, which are in turn aligned with one another in a complex global hierarchy of power. The Amazon, in this sense and others, is a peripheral region of still-peripheral countries, with its fate largely decided outside of it, and whose inhabitants – some of the most subordinated classes and oppressed groups of this periphery of the periphery – are those bearing the brunt of the tragedies induced by external capitalist forces and their state backers. Arraigned against these multiple scales of power are Amazonian indigenous and peasant resistances, informed by a knowledge of its rivers and forests honed over millennia.

In response to the thoroughgoing hypocrisy of Emmanuel Macron’s recent savior-posturing pronouncements on the Amazon at the G7 Summit, Porto-Gonçalves writes in Esquerda Online that, “more than the G7, or even by the set of Latin American states that exercise sovereignty over the Amazon, no destiny of the area should do without the input and knowledge of its indigenous inhabitants. The reproduction of this knowledge requires the metabolic conditions for the reproduction of their life per se, which, as we know, is not only biological, but also cultural, and, therefore, requires the recognition of their territories so that their territorialities are reproducible.”

In an echo of this sentiment, Luiz Henrique Arias, a Brazilian Amazonian inhabitant, activist, and intellectual, has recently signaled the dangers of referring to the Amazon in this moment of crisis as if it were an uninhabited natural reservoir. “One thing bothers us a lot when non-Amazons speak of our region,” Arias writes in Esquerda Online, “is that even within the leftist groups the vision of the ‘demographic void’ still prevails. We talk about the burnings and we are angry at the burning forest and the animals dying (the revolt against which is obviously just and worthy), but we forget that this whole territory is historically occupied by people, and that they are the main ones affected by the advance of agribusiness. It is these people who are not only affected by the burnings, but who have given their blood every day for decades for the right to live in their territory.”

For Arias, then, indigenous struggle will be pivotal to the survival of the Amazon per se. “So let’s spread the word, fight Bolsonaro’s necro-politics, denounce agribusiness, and speak out for the defense of our forests. But remember that when we talk about the Amazon, we are not just talking about burning woods, and animals being charred. We need to speak centrally of the human beings that reside here and have been violated every day for centuries. The struggle is one for our right to land, the river, nature and a dignified life. It is for the demarcation of indigenous and quilombola lands [quilombolas are descendants of runaway slaves who have a distinct legal and cultural status in Brazil], it is for agrarian reform and against the expulsion of peasants from their lands, it is for the right of traditional peoples to their territory and for the maintenance of the standing forest. This is our defense!”

As the Amazon burns, the world’s focus on Bolsonaro is understandable, and correct politically in the immediate scenario. But strategically it pays to remember the power of agro-industrial capital under the PT, as well as the role of such capital in Brazil’s neighbor Bolivia, where close to a million square hectares of the Chiquitania region is simultaneously engulfed in flames, under the very different government of Evo Morales. No social-democratic management of this crisis is possible, and in the medium-term only those strategic endeavors which take anti-capitalism as their genuine orienting horizon should be taken seriously as alternatives to more of this devastation. We require projects, in Brazil and internationally, that open our horizons to the monumental challenge posed by ecological crisis, and projects which do not offer an anti-capitalist horizon to that challenge are not just not up to that task, but a way of avoiding its construction. Such a project might prove impossible to build, but it remains necessary.

References

| ↑1 | Glenn Greenwald, Leandro Demori, and Betsy Reed, “How and Why The Intercept Is Reporting on a Vast Trove of Materials About Brazil’s Operation Car Wash and Justice Minister Sergio Moro,” The Intercept, June 9, 2019. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | While the CUT is by far the largest national labor federation, there are many others. Most of them aligned themselves with the PT while the party was in office – besides the CUT, this list includes Union Force (FS), a traditional adversary of the PT which nonetheless fell in behind the party during Lula’s second term in office, the General Confederation of Brazilian Workers (CGTB), the Brazilian Workers’ Central (CTB), the New Union Central of Workers (NCST), which was created in 2006, the General Union of Workers (UGT), created in 2007, and, finally, the Central of Brazilian Unionists (CSB), a product of a split from the CGTB in 2012. Because of the subordination of these workers’ federations to the programs of the PT in office, two more militant labor federations were formed as splits from the CUT – the National Coordinator of Struggles (Conlutas) in 2004, and Intersindical in 2006. Although these were minoritarian currents in the CUT, and remain relatively small now that they exist independently, they nonetheless represent important vectors of resistance to the hegemonic conciliatory unionism. See Armando Boito Jr. Reforma e crise política no Brasil: Os conflitos de classe nos governos do PT (Campinas: Editora Unicamp, 2018), 184-185. |

| ↑3 | Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser, Feminism for the 99% (London: Verso Books, 2019). |

| ↑4 | Paula Silva is a pseudonym. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine