The effigy of a black man, a son of Southern soil and descendant of slaves, now stands over the nation’s Mall among its founding fathers, notorious slave owner in front and the so-called Great Emancipator to his back. Looking out over the placid Tidal Basin with a steely-eyed reserve and chiseled determination, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, the first monument on the Mall dedicated to a man of color, has whipped up yet another tempest of protest. Besides the same types who did not and still do not commemorate the life of this influential Civil Rights leader on the third Monday of every January, other dissenters have noted that the veined, confrontational depiction of the Brother Preacher by the Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin does not evoke the round docility associated with the open-armed love of nonviolence. For them, the image goes against what they see as King’s true legacy, while others see the statute as an appropriate stance of well-grounded, stony defiance and pride.

Perhaps the best way to understand Martin is through his foil, the other Brother Minister, Malcolm X. As the chronicler of the black experience Manning Marable wrote in last year’s authoritative biography of Malcolm, “the leader most closely linked to Malcolm in life and death was, of course, King.” However, these two men were linked more by their perceived differences than they were known for their similarities. Malcolm was “widely admired as a man of uncompromising action, the polar opposite of the nonviolent, middle-class-oriented Negro leadership that had dominated the civil rights movement before him.” But if Malcolm was known for his action, Martin has been remembered for his results.

Despite their perceived divergence, Malcolm and Martin’s convergence is the essential condition for understanding the Black Freedom Movement and socio-political struggle in general, just as it was in the turbulent times when these two leaders were slain.

Though their constituencies were different – Martin’s Southern, largely rural base standing in contrast to Malcolm’s Northern and Western urban industrial community – their desire to develop black dignity insured an ongoing dialogue, even if Martin used a language of Christian integration-based citizen rights and Malcolm championed an Islam-inflected black cultural nationalism. In 1954, at the time that Martin was finishing his PhD at Boston University, Malcolm was preaching for the Nation of Islam, and according to Marable they walked the streets of the same neighborhood. Yet they would not meet in person until March 26, 1964, walking the Senate Gallery after a conference King had with Senator Hubert Humphrey and Jacob Javits. That these two figures, who embodied two different currents of the Black Freedom movement, met only once is remarkable. In the ten years between these dates much had changed with both men. But their streams of black consciousness and political action continued to both diverge and converge.

Though Malcolm often decried the Uncle Tom Negro leadership of which Martin was conceivably a member, he would rarely call Martin out directly, sparing the young energetic leader his typically pointed barbs. He spoke highly of the Montgomery bus boycotts and the courage of people like Rosa Parks. King, on the other hand, often used Malcolm to make his ideological platform and political practice more palatable for whites. In response to a June 1962 comment Malcolm made about God answering his prayers to kill 121 whites in a Paris-Atlanta flight, King assured the white press “that the hatred expressed toward whites by Malcolm X [was not] shared by the vast majority of Negroes in the United States. While there is a great deal of legitimate discontent and righteous indignation in the Negro community, it has never developed into large-scale hatred of whites.”

In spite of Martin’s attempts at distancing, it is no simple task to place these men as opposing forces. Both were what we might call institutional men. Granted, the natures of the institutions were very different. King came up in the black church, Atlanta’s black bourgeoisie, defined by the Black intellectual network of the Atlanta University Center and organizations such as the NAACP, ultimately arriving at the elite institutions of Crozer Theological Seminary and Boston University. Malcolm, on the other hand, came up against the backdrop of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, foster homes, the assembly line, and prison. Martin’s class position and Christian ideology positioned him in a conciliatory stance, whereas Malcolm, who shifted constantly between the working class and the lumpenproletariat, was prepared to separate from the entire system. Any discussion of these two men must start from this basic understanding. Martin had the material means and the social support to develop an entire intellectual program that he could start to execute at the age of 26, during the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. To be sure, King’s leadership and theory continued to develop through his career, but he remained a traditional intellectual, built into the structure of the clergy. Malcolm was an organic intellectual. He had to forge an independent philosophy from a patchwork of street smarts, prison libraries, and undying curiosity. His theory was forged by the fires of practice.

Even with their differing points of departure, observers have often noted that the two leaders seemed to converge near the ends of their short lives. The post-Nation of Islam Malcolm made a path from separatism towards internationalism. Marable argues that the 1964 meeting “marked a transition for Malcolm, crystallizing as it did a movement away from the revolutionary rhetoric that defined ‘Message to the Grassroots’ toward something akin to what King had worked his entire adult life to achieve.” Shortly after the meeting, Malcolm’s “Ballot or the Bullet” speech stressed voting rights and black political solidarity, implicitly diminishing the potential role of violence.

Martin’s militant opposition to the triple evils of racism, militarism, and exploitation, as manifested in the Vietnam War, recalled Malcolm’s anti-colonial solidarity with Asia and Africa, a rejection of the Western paradigm:

I’m convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, militarism and economic exploitation are incapable of being conquered.

What’s more, Martin, just as Malcolm, experienced extensive government surveillance. Documented in his FBI file, this surveillance reminds us that no matter how much the man is celebrated today, he was treated as a dangerous threat to national security during his life.

The obvious distinction between Martin and Malcolm almost does not need to be made. However, the nonviolence/violence dichotomy does not accurately depict the actual schools of thought in the struggle to achieve black subjectivity, nor does it allow for the type of evolution that we have already seen among the two thinker-activists. First, nonviolence does not imply that demonstrators are non-confrontational, or even the absence of violence. On the contrary, nonviolence is an aggressive passivity intended to incite a disproportionately violent response, exposing the morally bankrupt structure. This tactic – and many, including Martin, referred to it as a tactic – required an aggressive, courageous resistance. This method did not exclude the possibility of violence. As King himself wrote in 1958, “nonviolent resistance is not a method for cowards; it does resist…This is why Gandhi often said that if cowardice is the only alternative to violence, it is better to fight.”

Moreover, King’s early interventions did not exclude the protection of armed self-defense. In his recent Colored Cosmopolitianism, Nico Slate narrates a visit by a veteran civil rights activist: “when Bayard Rustin visited King’s home during the early days of the Montgomery boycott, he found armed guards on the porch and weapons scattered throughout the house.” It was not until much later in his career that nonviolence become an all-embracing philosophy for King. Even then, he admitted that for most black people, nonviolence would remain a tactic, at most.

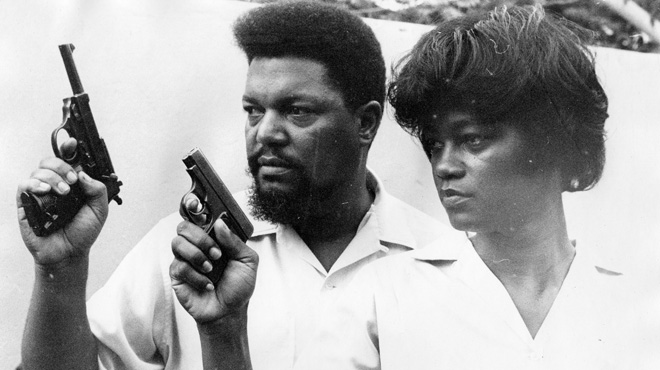

Meanwhile, throughout the south, armed self-defense became a promising approach to combat ruthless and murderous racists, the kind that left Medger Evers assassinated and four little girls dead. Few figures were as influential as Robert F. Williams in advocating armed self-defense to achieve safety and dignity for Blacks in America. Having labored in Northern industry and served in the Army during World War II, Williams returned to his North Carolina home – trained, disciplined, and radicalized. He rose to a leadership role with the Union County chapter of the NAACP, a position from which started to insist on the need “to meet violence with violence.” In 1957, Williams started the Black Armed Guard, with a charter from the National Rifle Association. The group probably saved many lives when on October 5, James “Catfish” Cole led a Klan rally that ended with a raid on the black part of town. The war veterans fought off the motorcade from fortified positions in trenches and foxholes with small arms. The next day, Klan motorcades, which had sometimes been escorted by police, were banned by the City of Monroe. The 1961 Freedom Riders foray into Monroe was intended to show the advantage of nonviolence. But when thousands of rioting Klansmen showed no respect for philosophy, Williams and his Black Armed Guard were called on to protect the demonstrators. Here nonviolence and armed self-defense worked together in a dynamic dialectic. At his funeral, Rosa Parks said that she and others who marched with Martin in Montgomery admired Williams’ contribution to the struggle. As Slate puts it, “the ability of nonviolent activists to mobilize Black communities depended largely on the capacity of local Blacks to physically defend activists…Nonviolent tactics and armed self-defense worked together to channel white violence into less deadly and more politically useful situations.” Williams’ book Negroes with Guns would come to be influential for younger black political actors, such as Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton.

A few months after their only meeting, Malcolm sent a telegram to Martin, extending an offer to help protect the nonviolent protesters in Saint Augustine, Florida who had been attacked. “We have been witnessing with great concern the vicious attacks of the white races against our poor defenseless people there in St. Augustine,” Malcolm wrote. “If the Federal Government will not send troops to your aid, just say the word and we will immediately dispatch some of our brothers there to organize self defense units among our people and the Ku Klux Klan will then receive a taste of its own medicine. The day of turning the other cheek to those brute beasts is over.”

Defensive violence, however, was not the only type of violence that militants in the Black Freedom Movement considered. Contemporary developments in China, Cuba, and Algeria seemed to make a convincing argument for an offensive armed revolutionary struggle. Even after his disillusionment with the Communist Party, Harold Cruse was forced to contemplate “the relevance of force and violence to successful revolutions” after visiting Cuba in June of 1960. “The ideology of a new revolutionary wave in the world at large,” he recalled, “had lifted us out of anonymity of lonely struggle in the United States to the glorified rank of visiting dignitaries.” Cruse asked, “what did it all mean and how did it relate to the Negro in America?” Marable’s biography of Malcolm shows that near the end of his life, with his connection to people like Max Stanford and the Revolutionary Action Movement, he anticipated the development of a revolutionary underground that would emerge later in the decade and in the 1970s.

If Martin and Malcolm’s divergence can be explored through their evolving stances on the use of violence, their convergence may be best assessed by stances along the axis of transgression. The Italian workerist Ferruccio Gambino’s 1993 essay, which recasts Malcolm’s life and legacy as a transgression of the logic of the state, captures this relationship:

Malcolm X – the laborer, the convict, and the minister of the Nation of Islam – had seen too many and too well the least-lit corridors of the state to avoid a collision with it. In this respect, his path was similar to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s. The young desegregationist minister of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference had seen so many black people suffer indignities during his early campaign in the South that he could only relate these to the cheapness of living labor there. Indeed, as early as 1957 he had said, “I realize that the law cannot make an employer love me or have compassion for me.” As King too began to walk away from the role the state had expected of him, he headed toward assassination while supporting a strike by black laborers in Memphis, Tennessee.

The transgressions of the entire Black Freedom Movement, though they have since been validated and subsumed into the narrative of liberal democracy’s ability to accommodate, encompass nonviolent conformist activities just as much as militant direct action, each equally criminal. The most potent transgression is the rejection of the state’s “gods,” its symbolic embodiments of power. Islam forced Malcolm “to occupy the double political space of ‘the immigrant,’” as Gambino argues, a “self-location” which “violated the written and unwritten codes of legitimate political behavior.”

Malcolm’s Islam was a symbolic and spiritual orientation to an Afro-Asiatic anti-colonial internationalism that struck a claim on politics outside the state’s monopoly of legitimate power. His transgressions, mental, criminal, and spiritual, are widely understood. But against Martin’s easy incorporation, we should remember that he, too, transgressed. It is true that the familiar and domestic language of Christianity of Martin made him acceptable to many Americans. However, couched in that language was the vernacular of a long tradition manifested in black liberation theology that signified on the master’s religion, developing a sometimes dormant, sometimes active opposition to white power. It is a lineage emerging from people like Richard Allen, who started the African Methodist Episcopalian Church in 1816 to create autonomy for black congregations. There are the likes of Henry McNeal Turner, an early “back to Africa” advocate and missionary who once said that “Hell is an improvement upon the United States where the Negro is concerned.” Turner’s own theology understood the symbolic power of the state’s gods:

Every race of people who have attempted to describe their God by words, or by paintings, or by carvings, or any other form or figure, have conveyed the idea that the God who made them and shaped their destinies was symbolized in themselves, and why should not the Negro believe that he resembles God as much as other people?

More direct influences on King can be found in the likes of Howard Thurman and Benjamin Mays. The two had visited Gandhi in India and worked towards establishing functional solidarities with South Asians during their struggle against the British Empire in the 1930s. Importantly, Thurman and Mays contributed to a theology that sought to isolate the religion of Jesus from its imperial uses.

Thurman, a classmate of Martin’s father and a mentor while Martin was at Boston University, and Mays, Martin’s mentor at Morehouse College, helped Martin to develop a transgressive philosophy. As Nico Slate writes, Martin was almost immediately hailed as the Montgomery Mahatma after beginning the boycott: “King’s connection to Gandhi strengthened his appeal to both blacks and whites. Gandhi represented courage, civil disobedience, and the rising colored world to many blacks while symbolizing non-threatening nonviolence to whites.” Slate argues that this double space of meaning did not prevent Martin from identifying race as only one variable in the equation of oppression. As King wrote of his visit “to the land of Gandhi” in Ebony magazine, “the bourgeoisie – white, black or brown – behaves about the same the world over.”

Today the legacies of both Martin and Malcolm benefit from an official acknowledgement of their contributions to the Black Freedom movement. This is largely because, as Gambino writes, “the attitudes of ethnic leadership towards the state are shaped over a long period of time, often being the result of continuous readjustments over many generations.” That there is such a grand official salute to Martin reflects that the state “often believes it can redress past wrongs with reforms that are supposed to have the effect of ‘cooling off’ both ethnic leadership and the people as a whole,” and that “the state’s late discovery of a collective symbolic reality one shade removed from its official gods has often ended in a redefinition of the state and its pantheon, or in the demise of both.” That Martin’s legacy today appears to tower over so many others indicates just how well he occupied the double space of meaning while acting for dignity and freedom. Now our task is to refuse the state’s gods and reach into our past, to recover the possibilities for future transgression.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine