A publisher is defined by his catalogue. But there is the catalogue of the books published, and then the catalogue – in any case much more important for me – of the books I haven’t published. And I’m very proud to see that there are many books I haven’t published. A third catalogue that one can have is the catalogue of the books published by other publishers because of one’s very existence … I’m very pleased to see piles of books that would not have appeared if I had not existed.

– François Maspero, 1970

François Maspero, born in January 1932, lived as an author, journalist, and translator. He is perhaps best remembered, however, not for what he wrote, but for what he allowed others to write.

The 1950s-1970s are familiar to many as a time not only of intense political struggle, but of global intellectual ferment – in France, anti-imperialism stirred the imagination of young radicals, Marxism was hotly debated, and new styles of thought were elaborated. Less familiar, no doubt, are the highly material – although now largely forgotten – networks that collected, edited, refined, circulated, and popularized those ideas. At the center of this dynamic nexus stood the often hidden labor of François Maspero. Easily one of the most important French editors and publishers of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, he helped, as historian Kristin Ross has shown, shape an entire intellectual terrain.

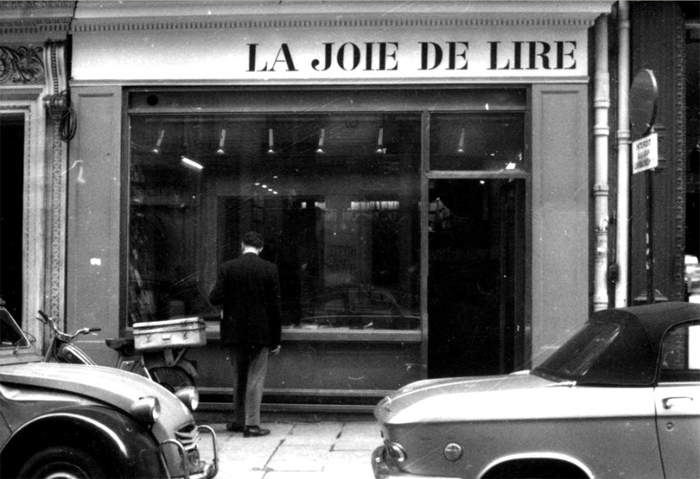

In 1956, when just 24 years old, Maspero opened the doors of his bookstore, La Joie de Lire, in the Latin Quarter. Four years later he, along with a few others, founded Éditions Maspero. Militant, exploratory, uncompromisingly rigorous, his books focused above all on decolonization, Marxism, and revolution. At a time when anti-colonial revolutions were overthrowing Western empires across the globe, Maspero, along with other publishers such as Giangiacomo Feltrinelli in Italy and Klaus Wagenbach in Germany, helped the ideas of these revolutions invade the heart of imperialism itself. He published books about Algerian liberation, accounts of torture, and of course Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth – all during the war itself, provoking constant harassment, lawsuits, and bomb threats.

In September 1961, he founded the anti-imperialist journal Partisans, and after the 1966 founding of the Tricontinental – which brought together delegates from Asia, Africa, and Latin America in the first international body organized by the Third World itself to overthrow imperialism – he distributed the organization’s quarterly in France, which in 1968 was officially banned by the government. Publishing the works of revolutionaries such as Võ Nguyên Giáp, Che Guevara, Mao Zedong, and Malcolm X, he proved that the greatest ideas ultimately derive from contemporary political struggles. The writer simply articulates the ideas implicit in these struggles; the publisher circulates them, casting them into a wider field.

But he also made possible the experimental wave of radical thought for which 1960s France is perhaps best known, reviving dissident thinkers like Victor Serge, and publishing contemporary unorthodox writers such as Daniel Guérin, Nicos Poulantzas, Michael Löwy, and Louis Althusser. Indeed, the latter’s decision to publish his monumental works with Maspero was perhaps one of the most influential moves in 20th century Marxism, symbolically marking Marxism’s escape from the crushing grip of the French Communist Party, even if Althusser himself strategically chose to continue waging the struggle from within. Maspero even allowed Althusser to direct the publishing house’s “Théorie” collection, which lasted from 1965 to 1981.

In 1967, Maspero launched the Petite collection Maspero, a set of affordable pocket books – featuring authors from Rosa Luxemburg to Fidel Castro – that composed the arsenal of the young radicals who fought in May 68 and the many struggles of the following years. During the raging street battles of May, his bookstore in the Latin Quarter served as both a headquarters and field hospital for militants – reminding us in our digital age that a radical intellectual terrain is not simply an abstract conceptual space, but, to have any kind of efficacy, necessarily implies a kind of physicality as well.

In the 1970 documentary Chris Marker made of him, Maspero suggested that perhaps what most defined a publisher was not what he or she published, or even didn’t publish, but what his or her very presence, in changing the intellectual field, had forced others to publish. Maspero not only revived radical ideas, forcefully inserting new themes, topics, and languages into circulation, but did so in such a way that forced other publications to shift their catalogues or risk becoming historically irrelevant. His own works may not be remembered, especially in the United States, but his effects certainly are, his fading fingerprints left on so many thoughts. Maspero was, in the cinematic sense of the term, a great producer of ideas – from the project’s sweeping vision to its tiniest details, from the theoretical concepts to the distribution network, from the library to the streets.

Today, as radical thought seems to be searching for its second (or third, fourth) wind, let’s not forget that radical, creative ferment comes not simply from intellectuals, but just as much from those who can best articulate the social movements of their times into the terrain upon which such ideas can continue to grow.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine