As the subtitle of the book emphatically asserts, Riot. Strike. Riot is conceived as a theory of the present, configured here as a “new era of uprisings.” In this intent, Clover’s coruscating essay joins a smattering of texts that have tried to baptize and orient the moment that blossomed into recognition after 2011 – essays and books by Alain Badiou, Alain Bertho, Théorie communiste, The Invisible Committee, Jodi Dean, Endnotes, and a few others. The theoretical resources and vocabularies that Clover enlists into his argument – with enviable clarity, economy, and focus – would reward attention on their own right. Most critically, the grounding claim that “a theory of riot is a theory of crisis” means that the persuasive power of Clover’s montage depends largely on one’s estimation of his splicing of Robert Brenner, Giovanni Arrighi and value-theoretical accounts of crisis to provide the logical and historical armature of the overall account. 1

Though “riot” (often invoked without definite or indefinite articles and in the singular) is meant to illuminate crisis, it is evident from the outset that the weight of theorizing rests on the theory of capitalism, and it is that theory which allows us to turn the toponymy of insurrection (Oaxaca, Oakland, Tahrir, Clichy-sur-Bois, etc.) into a forceful claim about the shifting shape of collective action against capital. Notwithstanding Clover’s noting of the etymological link between émeutes (riots) and emotions, and the insurrectionary invocations that pepper his writing, his theory of riot is not a phenomenology of rioting, a theory of the subject(s) of riot (except to the extent that riot is subject, I’ll return to this), or even an investigation into the material tactics and repertoires of contemporary uprisings. Nor is it a poetics of riot (for which the reader is better off turning to his recent poetry collection Red Epic). Where the physiognomy of collective action is concerned, notwithstanding illustrative references to of freeway blockades, port occupations and the antinomies of the movement of squares, the argument is of a fundamentally historical kind.

Here the sociological work of Charles Tilly serves as the schema permitting the projection of a historical-materialist theory of capitalist crisis and transformation onto multiple instances of collective action (and inversely, though the ascending movement from riot to system is, I would maintain, exemplifying and not properly constitutive). “If the riot looks at periodization, the period in turn peers back at the riot through the dialectical keyhole. It is hard, perhaps impossible, to establish what a riot is without periodization; with it, the riot (and the strike as well) can be understood as a set of practices in the face of practical circumstances, with or without an imaginary regarding the reflexive self-awareness of participants on which so many accounts rest” (43). A thorough appraisal of the interpretive machine that Clover has dexterously engineered in Riot would no doubt require an interrogation of its component parts: Is the amalgam of world-systems theory, political Marxism and value-critique stable? Is Tilly’s historical patterning of collective action – itself anchored in a non-Marxist historical sociology – mappable onto that historical-materialist fresco? 2 Can the riots really express and explicate our historical moment (105), serving as the “holographic miniature of an entire situation, a world-picture” (123)? What I want to address here is the overarching principle that governs the composition of the book’s various conceptual elements, and which in the final analysis is Clover’s name for theory: periodization.

Riot Theory

When Clover declares that what our moment demands is “a properly materialist theorization of the riot” it is a sui generis historical materialism he is calling upon (6). This is pitted against, on the one hand, sociologically-deterministic accounts of collective action as a forecastable reaction to given constellations of power and inequality, and, on the other, philosophically-voluntaristic and taxonomical accounts of the riot as a pre-political herald of a communist organization and idea to come, as in Alain Badiou’s portrayal of our “age of riots.” Though readers expecting a keen-eyed theorist of poetics such as Clover to delve into the aesthetic of riot will be disappointed, the forma mentis of Marxist literary criticism of a decidedly Jamesonian stamp is palpable. Periodization is conceived as the correlation of historically emergent social forms to political and not poetic forms, but the method and style of correlation will be familiar to readers of landmark essays like “Modernism and Imperialism” or “Culture and Finance Capital” – both of which pioneered this use of Arrighi’s work (though to Clover’s credit, his use of periodization aims at a less allegorical result). 3

The framework is striking and stark in its simplicity: melding Arrighi’s Braudelian account of cycles of productive and financial accumulation with Brenner’s diagnosis of the long downturn – with 1973 as year zero of our stationary or terminal age – Clover generates a three-ages theory of sorts, mapping, via Tilly’s sociology and E.P. Thompson account of 18th-century riots, ages of circulation, production and circulation (or, in his terms, circulation prime) onto long phases in which riot, strike and what he calls riot prime are the preeminent or hegemonic figures of collective action. This account is then supplemented with Théorie communiste’s take on the limits of anti-capitalist action, as we will touch upon below. In Clover’s synopsis: “crisis signals a shift of capital’s center of gravity into circulation, and riot is in the last instance to be understood as a circulation struggle, of which the price-setting struggle and the surplus rebellion are distinct, if related, forms” (129).

What are the presuppositions of this image of theory as periodization? First, and perhaps most momentous, is the notion that we must identify a “central figure of political antagonism” (3). This thinking of the present through central, dominant or hegemonic figures has become so commonplace on the left as to be often left unquestioned. It is almost invariably driven by the felt need to refute a traditional left’s attachment to obsolescent or anachronistic “figures” – party, union, strike, revolutionary grab for power. In this respect, Clover’s polemical schooling of labor-nostalgia on the U.S. socialist left has more than a few echoes of analogous asseverations by Italian post-workerist against stalwarts of historical communism, of French anarcho-communists against Trotskyists, and so on and so forth. The polemics often reach their target, but rarely if at all do they interrogate the founding attachment of what we could term the philosophy of history of collective action to a “leading tactic” (73) transmuted into a singular figure, “both a real fraction of and a figure for the many to which it is always adjacent” (73). Riot prime “names the social reorganization, the period in which it holds sway, and the leading form of collective action that corresponds to the situation” (28).

What compels us to transform a tactic or a form into a historical subject and substance? It is worth pausing here on Clover’s language – clearly pondered and chosen in full foresight of its effects. Contrary to those post-workerists for whom the figure is still, in however mutant a form, a collective class subject (the cognitariat or assorted cognates), in a gesture as captivating as it is potentially mystifying and fetishistic, it is “riot” (not the riot, or riots) which takes the agential or actant role from the outset. In elucidating how “riot is itself the experience of surplus” (1) – where the phenomenology or locus of that experience is curiously unlocalizable – Clover will write of the “moment when the partisans of riot exceed the police capacity for management, when the cops make their first retreat, [as] the moment when the riot becomes fully itself, slides loose from the grim continuity of daily life” (1-2). It is not rioters that face off against the cops, but “partisans of riot,” and while they are the surplus it brings into being, it is riot that is subject, “it” becomes fully itself, in an impeccably Hegelian turn of phrase. At times these partisans seem reduced to mere Träger or ventriloquists for this spectre haunting a deindustrializing world: “Riot goes looking for surplus populations, and these are its basis for expansion” (154). At others there is a fusion, with vitalist echoes, of riot with the biopolitics of exclusion: “Riot prime is the condition in which surplus life is riot, is the subject of politics and the object of ongoing state violence” (170).

Riot as subject, or the sublimation of a form of collective action into figure of history, is also a product of Clover’s determination – most compellingly delineated in his engagement with Luxemburg’s writing on the general strike – to identify necessary or historically inevitable forms of action in the present. Clover’s definition of theory is worth reproducing here: “Theory is immanent in struggle; often enough it must hurry to catch up to a reality that lurches ahead. A theory of the present will arise from its lived confrontations, rather than arriving on the scene laden with backdated homilies and prescriptions regarding how the war against state and capital ought to be waged, programs we are told once worked and might now be refurbished and imposed once again on our quite distinct moments. The subjunctive is a lovely mood, but it is not the mood of historical materialism” (4). But the logic of theory’s emergence and the character of its presentation here massively diverge. The contemporary practice of riots (and its remarkably recurrent repertoire) is not the source of the theoretical claims, rather it is the detour through the longue durée of periodization which reveals why “riot prime” is the uncircumventable form of action in our present. But riot as subject is also the grammatical complement to a claim upon the continuity-in-discontinuity of historical figures of collective action, what permits us to think through the spiraling “return” in the present (or even as the very political name of our present) of a form sidelined by the vast phase of struggles over production.

1973 and All That

The full stops in the book’s title reveal themselves as Marxian hyphens, tracing a circuit. What a theory of the present demands is “a periodization to match our practices: riot-strike-riot prime maps onto phases of circulation-production-circulation” (19), in which “the sequence riot-strike-riot prime does not suggest a simple historical oscillation but a long and arching development that both exhausts and retrieves forms as the contents and contexts of struggle change” (110). Again, I do not wish to interrogate here the content of these periodizations – the histories of capital and collective action whose deft interlacing makes up the bulk of the book – but the principle of periodization itself.

Periodization is also politically critical to the manner in which Clover articulates his relation to Marxism. Its upshot is that a proper historical-materialist correlation between phases of accumulation and modalities of struggle results in a near-apodictic certainty about the irrelevance of traditional Marxist politics, in its nexus of union-strike-party-revolution. In this crucial gesture, Clover’s book shares much with the communizing critique of contemporary Leninism and socialism, namely a putatively “classical” adherence to Marxist tenets whose polemical target is contemporary partisans of traditional Marxist politics. A crucial footnote specifies: “Marxism being not a political belief (much less a program), but rather a mode of analysis” (89n1). Clover’s book thus doubles as a “Marxism of Marxism” (second-order Marxism or Marxism squared, if you will), which provincializes the residually-dominant conception of Marxist politics as bound to the long nineteenth century of the strike. This marks it out emphatically from the two other lead theoretical treatments of the “age of riots,” Alain Badiou’s Rebirth of History and Alain Bertho’s 2009 Le temps des émeutes (not tackled in Riot), especially from the latter, for which the rise of riots is not just a termination of the political but of the analytical vocabulary of Marxism.

The wager that Marxist analysis can be desutured from Marxist politics and programs is bold and partly persuasive – after all, if the fate of Marxism were dependent on trends in union density or strike rates its death-knell would be tolling ever louder. As Clover correctly warns: “A class politics of even the most recondite or reductionist variety is now compelled to refigure itself according to these great political-economic transformations or consign itself to the endless role-playing of a backdated romance to which the perfume of 1917 always clings” (145). And yet there is a blindspot in this proposition, namely that periodization as theory is not so easily separated from periodization as program. As a reckoning with the historical-logical tendencies of capital within which given conjunctures are situated and collective antagonism operates, periodization, I would propose, is an implicitly strategic concept – as a century of Marxist debates about modes of production, transitions, and social formations suggests, from Lenin’s The Development of Capitalism in Russia all the way to 1970s discussions about the shift from “mass worker” to “social worker.” What’s more, notwithstanding the anti-organizational animus of Riot, which seeks to cleave to the demand-less inevitability of surplus rebellions, the sedimented forma mentis of periodization still impels Clover to introduce quasi- or para-strategic notions like “absolutization” and “commune.” These two names for the process and form of what, to court anachronism, we could call revolutionary politics retain from the programmatic register in which Marxist periodization has always functioned (for good or ill) a determination to orient, if nothing else away from the compulsion to repeat a stereotyped revolutionary sequence.

Clover is right to be suspicious of theory as the anticipatory (and thus often fantastical) organization of action, the enlightened forecast orienting cadres. But retaining the periodizing form of Marxist discourse, which has historically bound analysis to program (even if the latter is shame-faced or reduced to mere mood and negativity), begs the question of what or whom such a theory is for. With no strategic or pedagogical pretensions, Clover displaces programmatic prescription into polemical proscription, as though the periodizing narrative served principally to underscore the futility of a traditional image of political action, the “backdated homilies” he castigates. Ironically then, the centrality of periodization “concerned precisely with the degree of capital’s technical and social development … in all its eloquent and ambiguous undulations,” is aimed at undoing the very purpose of periodization in Marxist theory hitherto (17). An analytical correlation between the present shape of accumulation and the leading tactics of action would serve not to delineate the contours of a “leading subject” or organization, but precisely its impossibility. This, in a way, is Clover’s specific contribution to the “ideology of collective action” (82).

As he nicely articulates throughout these practical ideologies can be understood – whether we consider E.P. Thompson, Sorel, Luxemburg or the lived discourses of class struggle – in terms of an abiding contrast between strike and riot, through the “antithesis of forms of action” (89). Clover’s recounting is at its sharpest and most captivating when dealing with those transitional moments – riot to strike, strike to riot prime – in which we witness the dual presence and ambiguity of the ideal-typical forms of strike and riot (16). Whether assaying machine-breaking in the Swing riots or outlining the graft of riot onto strike in the Detroit Uprisings, as illuminated in a scintillating passage by James Boggs, Clover rightly checks his own tendency to an ideal-typical segmentation of collective forms to reflect on the “volatility of [riot and strike’s] dual presence” at critical moments.

It is striking that little is said about the concept of revolution here, though Clover’s form-history could provide a fine starting point for revisiting that idea. After all, revolutionary or proto-revolutionary moments – 1871, 1917, 1956, 1968, 1977 (to allegorize dates rather than places) – all appear to require the articulation of these forms. If a historical lesson can be drawn from revolutionary conjunctures it is that they are dominated precisely by the heterogeneity and combination of political forms, and the unevenness of times. Such unevenness – and not the synchronization between the historical logic of capital and the figures of collective action – is the “norm.” Here lies, to my mind, the most questionable presupposition of Clover’s book, which thinks transition as a political-economic or historical-sociological category - in other words “objectively” - underestimating its properly political valence. At one point, Clover writes that it “is precisely the transition from marketplace to workplace, from the price of good to the price of labor power as the fulcrum of reproduction, that dictates the swing from riot to strike in the repertoire of collective action. In fact, these are the same, context and conflict” (69). Yet the Brenner framework underlying the periodization is largely inimical to the notion of conflict determining context, and certainly to any notion that it is principally the age of strikes that lies behind the crisis cresting in 1973, such as one might encounter in operaista narratives. 4 Rather than thinking transition primarily through the world-history of capital generated by the melding of Brenner, Arrighi and Tilly, might it not be more effective to think of the condition of transition (of the kind traced here in machine-breaking or the “black militant strike”) as much more illustrative of contemporary struggles than the “pure strike” or the “pure riot”? 5 The desire for a correlation between the periodization of capital and the periodization of struggles is responsible for the fallacy of treating logical forms or ideal-types as concretely revealed in practice. It also involves an unwarranted and unprovable presupposition – shared with other philosophies of history of anti-capitalism, post-workerism among them – of a synchronicity and correlation between capitalist phase and anti-capitalist form. Why should tactical repertoires match the periodization of capital, especially since the criteria of periodization differ considerably? According to what schematism can a quantified archive of punctual events be projected onto a method of tendency based on a grasp of the abstract dialectic of social forms?

Here it might be interesting to briefly turn our attention to a nowadays rather neglected Marxist theorist of periodization: Ernest Mandel. In the midst of 1980s debates over the nature and span of long waves of capitalist development, Mandel proposed – in the ambit of a “dialectical, parametrical socioeconomic determinism” not a million miles from Clover’s inspiration – the thesis of a desynchronization of cycles of capital accumulation and crisis, on the one hand, and cycles of class struggle (and revolution), on the other. 6 In various writings, Mandel argued for class struggle as an independent variable with relative autonomy, more specifically claiming that what lent downturns and upturns in cycles of accumulation their asymmetry was that class struggle as a partially “exogenous” factor was crucial in determining the shape of a new round of accumulation. Moreover, class struggle itself is marked far more by the outcomes of a previous cycle of contestation than by the present shape of the capital-labor relation. 7 Overall, and notwithstanding convergences “in the long run”:

It is impossible to establish any direct correlation between [the] ups and downs of class struggle intensity on the one hand, and the business cycle, or “long waves,” or the level of employment/unemployment on the other hand. The conclusion is obvious: there is a definite de-synchronization between the business cycle and the cycle of class struggle. The level of class militancy of the workers at a given moment is much more a function of what happened over the previous fifteen to twenty years in the class struggle than of the economic situation (including the degree of unemployment) hic et nunc. 8

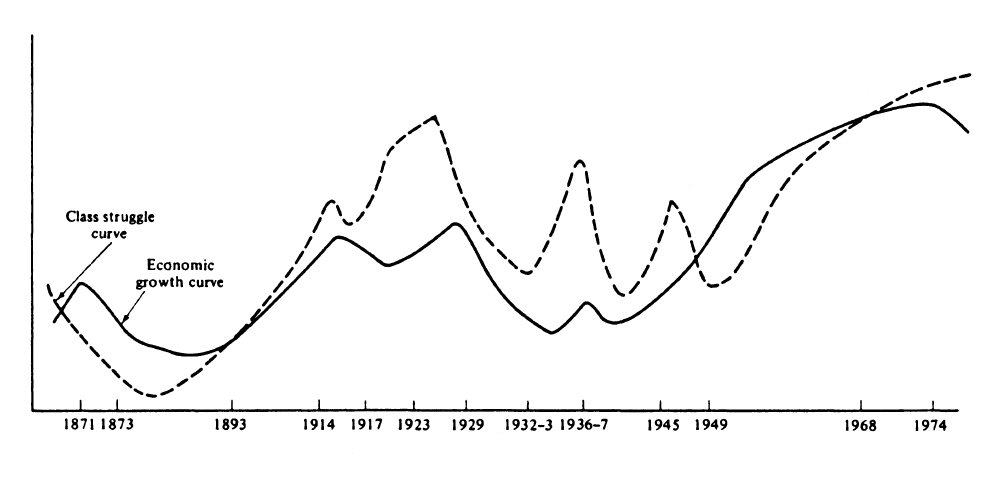

Mandel’s proposal of a “dialectic of uneven and combined development of current economic trends, working-class reactions and economic end results, in which the structural dependence (subordination) of wage labor to capital is combined with the relative autonomy of working class reactions (struggles)” translates into the following image (drawn from Long Waves of Capitalist Development, 39) of the somewhat sinusoidal, syncopated double step of capital and labor – the desynchronized rhythm of antagonism.

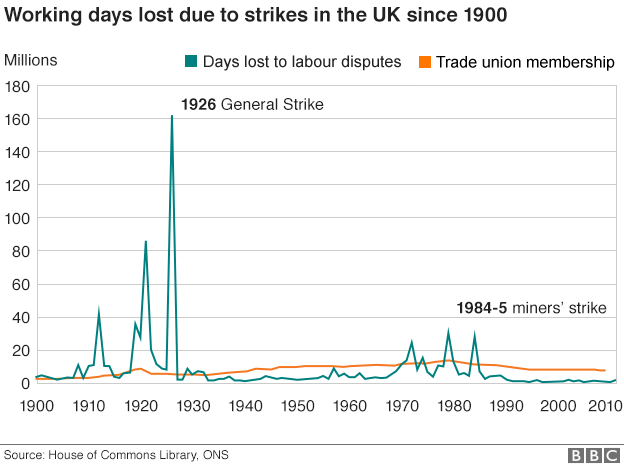

Moving away from long waves, we might also wonder whether the vastness of Clover’s historical canvas –in which 1848 is closer to 1967 than 1967 is to 1977 in terms of the relation between capital and collective action– doesn’t risk losing many of the undoubted virtues of thinking the rhythms of conflict in conjunction (but not lockstep) with the rhythms of accumulation. For instance, notwithstanding the broad strokes with which the epochs of riot, strike, and riot prime are connected to circulatory and productive phases of accumulation, the historical partitures advanced in Riot complicate matters considerably, on the ledgers of both capital and labor (or anti-capital). In the Braudelian graph presented by Clover (18), for instance, much of the eighteenth century is dominated by the logic of production and the period between the 1880s and the 1940s by that of circulation, though the latter largely overlaps with the heroic period of strikes in the West and beyond. This doesn’t quite chime with the claim that “productive capital held sway from, say, 1784 to 1973” (20) and that strike is “the form of collective action proper to the productive phase of capital” (85). But consider also the pattern of strike incidence in Britain which – in the whole period following the suppression of the 1926 general strike – was actually higher in “circulation” than “production” periods, spiking over 1973-1985, while being remarkably dormant before. 9

In this respect, to say that the strike “survives as a leading tactic in the industrialized west through the sixties” is a bit peculiar, unless we think of it more specifically as a strike against the shift to circulation, against deindustrialization. This view would be strengthened by the recognition that the strike – no doubt due to the integration of the labor movement in Fordist state strategies – is a rather dormant tactic in much of the overdeveloped world in the peak periods of the productive phase. Thus, the “logically necessary causality” (107) between taut labor markets, industrial expansion, high profit rates and strikes doesn’t materialize, and the “heuristic smoothing” advocated by Clover blurs the unevenness, syncopation and granularity that might allow the periodization of capital to illuminate the modalities of collective action. It is not that the sequence riot-strike-riot prime couldn’t inform a history of capitalism, but it cannot attain identity with it, it cannot serve as “testimony about the status of capitalism as such” (21). Where a “distant reading” of collective action and capitalist transformations as practice herein may sustain a broad lamination of riot and “circulation,” strike and “production,” attention to conjunctures of accumulation and struggle in the postwar period largely belies the narrative that rising accumulation was the condition for successful socialist action (145). Not only have strikes often been higher in incidence and impact during the the effective or imminent contraction of labor markets, an inauspicious economic climate and political volatility, but revolutionary politics – whether of a communist, anarchist or anarcho-syndicalist type – has never depended on those conditions, either in the overdeveloped world, or, patently, in the rest. This is not to say that, to paraphrase Tronti, struggles can’t take place at the strongest links in the chain, but surely that cannot be assumed as a norm.

This of course should pose no mystery for a Marxism drawing on the well of left-communist traditions, for whom the strike as a regulatory element in the state-led reproduction of capital-labor relations during periods of ascendant accumulation is a given (just think of Cold War unionism in the United States). Following Théorie communiste, Clover presents the present complexion of the capital-labor relation in terms that posit class belonging qua external constraint as “the limit for labor struggles as revolutionary engine.” Though, as the predicament of labor struggles in Argentina, Greece, and elsewhere shows, there is much truth in stressing the predicament of a class compelled at times to depend the reproduction of the capital-relation under punitive conditions – what here goes by the name of the “affirmation trap” – this should not serve by contrast to argue that the preceding phase was in the main one of even implicit revolutionary élan, nor to minimize how it too was shaped by the political and economic blackmail, so to speak, of reproduction. Moreover, cleaving to the Théorie communiste narrative also risks thoroughly reifying the limits of struggle, such as arguing as though it were an incontrovertible objective fact that: “The social surplus accompanying accumulation has dwindled” (151). 10 This is not to revert to social-democratic illusions about our condition being one of mere maldistribution, but it should be possible, without ignoring the fetters imposed by capital accumulation, also to recognize that the social surplus is politically constituted, and that “the state’s inability to apportion resources” is also its rank unwillingness to do it, due to political class constraints that cannot be chalked up to contractions in accumulation alone.

It Goes Round and Round Day and Night, and Will Be Consumed by Fire

Clover’s powerful delineation of our new era of uprisings depends for its periodizing thrust on the mapping of riot prime on “circulation prime,” the Arrighian name for the present planetary phase of capital accumulation. Here Clover, no doubt pivoting upon the Oakland Occupy blockade, echoes pervasive debates on the place of “logistical” and related struggles to the current fortunes of antagonism. Having already waded into this stream in the pages of Viewpoint, I want to limit my comments here to the preconditions for the periodizing move, namely the limning of circulation. My impression is that the polysemy, in Marx and beyond, of the term “circulation” is doing much of the work that permits the binding of the historical logic of capital to the vicissitudes of collective action. This is, for instance, the way in which an act such as blocking a freeway – more significant as a symbol of interruptive power than as any kind of severance of commodity chains – can be treated as a strike against the circulation of capital. Clover writes of a “world of circulation” (121), but one may be forgiven for thinking that the unity of this world is purely contrastive, polemically arrayed against the world (or indeed the fantasy) of a perfect nexus of accumulation-productive labor-factory struggles-revolutionary horizon which haunts the rhetoric of the socialist nostalgics that draw Clover’s critical contempt. Clover declares that “riot and strike are collective personifications of circulation and production at the limit” (121). But is the circulation that riot (negatively, antagonistically) personifies that of finance, logistics or consumption? All three? Are we so sure these are all bound into a unity, so as to bring a “world” into being? Isn’t a contemporary port more like a factory (in essence and appearance) than like a market? And can we declare the abstract logic of circulation to be spatial (138) if its financial facet depends so much on temporal arbitrage?

I don’t seek to gainsay the evident fact that struggles at the point of production classically conceived have long been on the wane, and that Clover is largely justified in his sardonic skepticism for “backdated homilies.” What I’m more doubtful of is the mapping of current struggles onto “circulation.” This appears as a shortcut to fitting them within a curiously orthodox and restrictive conception of all meaningful struggles as articulated to the history and logic of capital. Thus, while referring to the riot as a circulation struggle foregrounds the significance of some of the spaces in which it eventuates (the square, the street, more rarely the freeway or the port), the passage from that acceptation of circulation to its strictly political-economic meaning – key to Clover’s understanding of theory as periodization – is far more precarious. “Circulation is value in motion towards realization; it is also a regime of social organization within capital, interlocking with production in a shifting relation whose disequilibrium appears as crisis” (175), Clover writes. But even if we counter-intuitively accept circulation as the name for a regime of social organization, how it is articulated to circulation in the more everyday sense of roads or even markets is uncertain, unless the negation of the ideal-typical (but always minoritarian) figure of the factory is our sole compass. When Clover observes that “the riot is a circulation struggle because both capital and its dispossessed have been driven to seek reproduction there” (46), the “there” of circulation is uncertain. The context of the conflicts at Tahrir or Plaza del Sol or Occupy Wall Street, or indeed across the U.S. Black Lives Matter movement, is no doubt that of the ongoing crisis, with its lessons about the limits of capital accumulation and production of surplus populations. However, the term “circulation struggle” posits an identity and an objective orientation that belies the largely political character of such struggles, the fact that in their form as demonstrations (along with sundry forms of direct action and ideological work) and not riots their parameters and repertoires are hardly specified by the political economy of circulation.

The State of Reproduction

Clover is more compelling when the riot/strike transition is treated more as an uneven matrix than as the production of phases or eras where the form of capital and the form of struggle would reach a dubious synchronicity. The focus on reproduction, introduced through the dialectic of consumer and worker is a case in point. Resisting a smooth passage from consumption (circulation?) to production, Clover writes of “two momentary roles within the collective activity required to reproduce a single class” (15). He elucidates reproduction through the prism of transition, writing insightfully about the “double change” of capitalist context and collective conflict, and he defines riot and strike “not according to given activities but rather to the ways that the problem of reproduction confronts the mass of people, their positions within the given social relations, the places where they have been pushed, the spaces where their antagonists must be visible, might be vulnerable” (70). Yet I think that when we scale down from Arrighian centuries to politically meaningful conjunctures, we should think transition through reproduction and not vice versa, avoiding the philosophical-historical temptation to anoint a hegemonic figure as fully timely and synchronous – a position that Clover, despite cautions peppered throughout the text, in the end undersigns. To do this however, we also need to avoid the temptation, as with circulation, to turn a complex articulation and polysemy into a world-historical synonymy: the reproduction of capital (as understood, say, in Marx’s diagrams from vol. 2 of Capital) and social reproduction are intimately bound together, but they are not the same. Sometimes, Clover seems to rely on homonymy to speed the argument along, for instance writing that: “The strike ascends when the site of proletarian reproduction moves to the wage, which must at the same time become the crux of capital’s own circuit of reproduction” (86).

But the articulation of the reproduction of capital with social reproduction is an eminently political question, especially when the transition from strike to riot prime is so entangled with the fortunes of the state. A historicized theory of the state as an agent in the process of reproduction seems the biggest absence from Clover’s canvas. It is peculiar that, whilst much of the physiognomy of riot prime is drawn from a linking of capital forms to those of collective action, bypassing the phenomenology of riot, when it comes to the state, we are instead taken to the abstracted point of view of riot itself, where the state is the police. Clover makes the very astute comment that in contemporary riots “the state is near and the economy far” (126), and rightly poses the fetish of the police as a kind of practical aporia, but his explanation of it is partial. The state is near not just because of the neoliberal hypertrophy of its repressive function, but because, at least since the beginning of the twentieth century, it has always been near, its intimacy that of need and violation. When the economy was “near” to struggles, in the periods of industrial conflict at the point of production, so was the state – and not just repressively, but as one of the stakes of the struggle. The last wave of mass industrial action in Western Europe showed the depth and volatility of that entanglement, in which the wage and the social wage were not separable. The social wage is key when we talk of “surplus population confronted by the old problem of consumption without direct access to the wage.” Likewise, it is difficult to deny the massive part that what we can call a desire for the state plays in the nostalgic regulatory horizon of many of the signal moments that Clover name-checks, not least those in Greece, Spain and the United States.

Stressing the inevitability of the new figure, Clover suggests we approach “riot as a necessary relationship with the current structure of state and capital, waged by the abject – by those excluded from productivity. But it also points to the riot’s dependence on its antagonist. In the moment, the police appear as necessity and limit” (47). But, at least in the overdeveloped and deindustrializing world that forms Clover’s stage, many of the partisans of riots are not in any way fully excluded from reproduction, nor can they be properly or usefully defined as “abject.” I would go further, and say that it is not at all clear, for good or ill, that the state is entirely an antagonist (no more than it was simply an antagonist for even the most militant of strikes in the Western world throughout the twentieth century). At the limit, it may indeed turn out to be, but whether that limit appears or is reached as such is the question. I do not share Clover’s catastrophist confidence. Without taking on the state in both its material and its symbolic dimensions, the antinomies of contemporary collective action, marked by a refusal of and desire for the state in the vast majority of its instances, are difficult to confront. And reproduction, through the state as a material agent in the domain of political economy, is almost always embroiled with representation.

The Moral Economy of the Racialized Crowd in the 21st Century

This nexus of reproduction and representation is critical to approach a question that Clover rightly and compellingly puts at the pivot of his reflections, that of race and racialization. As he announces at the outset: “Increasingly, the contemporary riot transpires within a logic of racialization and takes the state rather than the economy as its direct antagonist. The riot returns not only to a changed world but changed itself” (11). The contemporary riot is defined as “a surplus rebellion that is both marked by and marks out race” (27). The state as the murderous, carceral bulwark of U.S. racial capitalism is no doubt the key antagonist of movements like Black Lives Matter, but it is not just an antagonist, just as the structure of U.S. racism means that brutal state violence is by no means visited simply upon the “abject.” Here Clover’s echoing of contemporary theoretical discourse on anti-blackness, with its tendency towards the metaphysical, risks absolutizing a link between racial violence and capitalist exclusion, while also implying a functionalist bond between race and capital. 11 He writes: “The riot is an instance of black life in its exclusions and at the same time in its character as surplus, cordoned into the noisy sphere of circulation, forced there to defend itself against the social and bodily death on offer. A surplus rebellion” (122). While surplus rebellion in this characterization may be a moment in the struggle against a racial capitalist state, a focus on abjection and exclusion, bolstered by taking a putative tendency to the production of absolute surplus populations as more or less present fact, can distract us from the tenacious continuities in struggles against racism in the United States and beyond, across and almost irrespective of the periodizations of capital – testament, among other things, to the relative autonomy of the structures of white supremacy. To map the civil rights struggle onto “production” and present struggles to “circulation,” with the period of the Detroit uprisings as the transitional crux is neat, but not persuasive, not least because it doesn’t confront the relative autonomy of “race,” and of the vocabulary of representation and recognition it carries in its wake from the undulations of capital. Stuart Hall’s work on riots, race, and class, invoked to fine effect in the pages of Riot, is both an excellent guide to a judicious use of Marxian categories like surplus populations in the present, and a reminder that there is no easy bypassing of representational discourses.

Yet from the start of Riot, Clover makes it very clear that he will have no truck with explanations operating at the level of subjective belief or phenomenology, no mind the emotion in émeutes. I am not sure that such anti-humanist iconoclasm is sustainable when it comes to riot, especially when the latter is articulated – as it certainly has been in movements like Black Lives Matter – in vocabularies of dignity and recognition (in a non-liberal sense of the term). 12 Already in dealing with the formative reference to the moral economy of the eighteenth-century crowd, Clover strives to evacuate the ethical thrust in Thompson’s social history of collective action. This is particularly marked in his claim vis-à-vis the first wave of circulation or market riots that, contrary to the workers’ identity of strikers, rioters have “no necessary kinship but their dispossession.” But the crux of the moral economy argument is that the antagonistic force of price-setting is precisely based on a deeply substantive collectivity, of habits, beliefs, norms, morals. Neither in the eighteenth century nor in the twenty-first does the unity of the antagonist (capital) make for the consistency or coherence of collective action. Riot does not synthesize collectivity from a mere pulverized mass, and rioters are not “unified by shared dispossession” – as the sadly ample record, past and present, of riots between differently racialized surplus populations suggests. Recalling Thompson we could counter the claim that “it is the character of bourgeois thought to preserve moral rather than practical understanding of social antagonism” (37), with the deeply moral vocabularies and motivations of much rioting. Though it is no doubt articulated with the capitalist production of surplus populations, the slogan “Black Lives Matter” is an eminently moral, which is not to say moralistic or idealist, one. 13 Likewise when people call police “pigs,” bosses “bastards” or British Tories “scum,” these are not mere screens for a practical logic of antagonism that neatly expresses capitalist contradictions. And, as Alain Bertho’s Les temps des émeutes has detailed, the very refusal of political representation that innervates many contemporary uprisings can also be understood in a sui generis “moral” sense, namely as the negation of a system that holds you, severally and collectively, to be nothing. The non-strategic, anti-historical time of the riot as elucidated in Furio Jesi’s formidable “symbology of revolt,” Spartakus is also the arena for a moral, and willfully “impractical” language of antagonism:

The adversary of the moment truly becomes the enemy, the rifle or club or bicycle chain truly becomes the weapon, the victory of the moment – be it partial or total – truly becomes, in and of itself, a just and good act for the defence of freedom, the defence of one’s class, the hegemony of one’s class. Every revolt is battle, but a battle in which one has deliberately chosen to participate. The instant of revolt determines one’s sudden self-realization and self-objectification as part of a collectivity. The battle between good and evil, between survival and death, between success and failure, in which everyone is individually involved each and every day, is identified with the battle of the whole collectivity – everyone has the same weapons, everyone faces the same obstacles, the same enemy. Everyone experiences the epiphany of the same symbols – everyone’s individual space, dominated by one’s personal symbols, by the shelter from historical time that everyone enjoys in their individual symbology and mythology, expands, becoming the symbolic space common to an entire collective, the shelter from historical time in which the collective finds safety. 14

The form of periodization seems at odds with this internally unperiodizable punctum of the riot (and its phenomenology) just as it jars with the traditional strategic horizon of periodization (qua tendency, conjuncture, or philosophy of history bound to an organized project of transition), raising the question of for whom do we periodize: if the riot has no demands why would it (unconsciously) require a philosophy of history, an epochal now to match its experiential here?

The Limit and the Absolute

Yet the armature of periodization, which in Clover provides the rationalist check on the rhetoric of riot that has pervaded kin efforts, not least those of the Invisible Committee, does issue into a final speculative sally, where the political-economic analysis of the limits of collective action is parlayed into an openly catastrophic wager on the absolutization of riot. This is the least compelling moment, to my mind, in this acute and galvanizing essay. Where experience and phenomenology had been sidelined as potentially moralizing impediments to the understanding of surplus rebellion, the subjective comes back with a vengeance, inevitability gliding into voluntarist prophecy. While the self-awareness of subjects seems of little moment, Clover seems happy to treat riot itself as Subject, invoking it in the following terms: “It cannot be refused. The riot can do only one thing, and that is expand” (123). There is something here of the “historical mysticism” that Gramsci criticized in those communist positions that saw crisis as substituting for practical agency or orientation. 15 The earlier note is the more sober and compelling one: “This is the dialectical theme, this dilemma of necessity and limit. The marketplace, the police, circulation. These are not situations where any final overcoming is possible; they are where struggles begin and flourish, desperately” (48).

Especially given the vocabulary of logic and necessity, for whom do we speculate about a process of which there are no present signs, that of the generalization, intensification, and correlation of riot as a kind of pure negation of capitalist reproduction? The dismal prospects of a redistributive, regulative escape from the present permanence of crisis is not reason enough to warrant “absolutization,” nor is the dim silhouette of a “renewed socialist program” (187). Too much of this concluding narrative is mortgaged to the idea – whose historical record in the age of strikes speaks for itself – that increasing immiseration is a driver of concerted challenge to the system, and that an increase in the incidence of revolts announces their coming composition. Banking on the utter fraying of state and capital, on a “great disorder” from which will rise “a necessary self-organization, survival in a different key” (187) is weirdly optimistic for a text with such a keen emphasis on the “limits” of struggles. Why fill in the formal gap in the periodizing theory with this unnecessary hortatory content? Why even name the commune, if it is not a social form or relation, but (as the book’s last line declares) “nothing but the name for … a peculiar catastrophe still to come” (192)?

Clover tells us that “the coming communes will develop where both production and circulation struggles have exhausted themselves” (191). But what compels reliance on a purely speculative dialectic of limit and novelty, when the book has shown such insight into the admixture and entanglement of forms of collective action, from fourteenth-century Norfolk to twentieth-century Michigan? We can’t exercise punishing sobriety regarding the chances of traditional proletarian conflicts at the point of production while infusing what are still remarkably weak, disconnected, and often politically ambiguous riots – whose main use thus far has been as occasions for strategies of state and capital – with such strong messianic power, especially when the conditions of their scalability and articulation are entirely enigmatic. We are told that “such struggles … cannot help but confront capital where it is most vulnerable.” But they haven’t yet, except in dress rehearsals whose significance is still allegorical or prefigurative at best. Though I can’t begrudge Clover for giving himself a prophetic license his periodizing framework had boldly eschewed, I would contend that this indispensable contribution to current reflection on modes of collective action, emergent and residual (riot is in a sense both), also shows how difficult it is for the instruments of periodization not to mutate into the slogans of a philosophy of history, where practice becomes portent, a weight contemporary riots do not seem capable of bearing.

This article is part of a dossier entitled The Crisis and the Rift: A Symposium on Joshua Clover’s Riot.Strike.Riot.

References

| ↑1 | Joshua Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (London and New York: Verso, 2016), 1. Subsequent citations are noted in the body of the text. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It is interesting to note that Tilly’s approach to collective violence inspired a compelling critical survey of 1960s black urban insurgencies which argued strongly against marginalisation and deprivation approaches, and for grasping these riots in terms of a “politics of violence.” See Joe R. Feagin and Harlan Hahn, Ghetto Revolts: The Politics of Violence in American Cities (New York: Macmillan, 1973), which proposes we view “ghetto riots as politically disruptive acts in a continuing politically motivated struggle between competing vested interest groups on the urban scene … in the main, collective violence was occasioned by the failure of the existing urban political system to respond adequately to their desires and aspirations, to allow them a proportionate role in the urban structure of power. Ghetto riots, therefore, reflected an attempted reclamation of political authority over ghetto areas … Collective political violence may well represent the ultimate act of popular sovereignty” (53). |

| ↑3 | A more comprehensive reckoning with Clover’s uses of periodization would certainly need to take account of his Marxian objections to the articulation of narrative and periodization in Jameson, and his alternative speculations on the relationship between poetic form and finance capital. See “Autumn of the System: Poetry and Finance Capital,” Journal of Narrative Theory 41, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 34–52, especially the concluding remark: “we should not finally restrain ourselves from a dialectical reversal of Jameson’s terms: the diachronic and narrative ‘passages’ of the mode of production are in fact synchronized by late capitalism. They are transformed to serve as a phantom space when the hegemon is no longer able to forward its accumulation via real expansion. This leaves non-narrative – that ‘poetics’ including poetry – better situated to grasp the transformations of the era: a more adequate cognitive mode for our present situation” (48–49). Perhaps the poem is to the novel what the riot is to the strike. |

| ↑4 | See Werner Bonefeld’s critical reflections in “Notes on Competition, Capitalist Crises and Class,” Historical Materialism 5 (1999): 5–28. |

| ↑5 | The recent writings of Jairus Banaji (Theory as History), Harry Harootunian (Marx After Marx), Gavin Walker (The Sublime Perversion of Capital), Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson (Border as Method) on transition, history, and politics are indispensable references here. |

| ↑6 | Ernest Mandel, “The International Debate on Long Waves of Capitalist Development: An Intermediary Balance Sheet,” in New Findings in Long Wave Research, eds. Alfred Kleinknecht, Ernest Mandel, Immanuel Wallerstein (New York: St. Martin’s Press; London: Macmillan Press, 1992), 331. He continues: “I contend that the second version of determinism, which sees two or three possible outcomes for each specific historical crisis - not innumerable ones for sure, nor ones unrelated to the basic motive forces of a given mode of production, but definitely several, corresponds both to Marx’s theory, and to Marx’s analytical practice.” |

| ↑7 | Ernest Mandel, “Partially Independent Variables and Internal Logic in Classical Marxist Economic Analysis,” Social Science Information 24 (September 1985): 485–505; here 496. See also Mandel, Long Waves of Capitalist Development: A Marxist Interpretation, 2nd rev ed. (London: Verso, 1994), 37–38, 119–20. |

| ↑8 | Ernest Mandel, “Partially Independent Variables and Internal Logic in Classical Marxist Economic Analysis,” Social Science Information 24 (September 1985): 485–505; here 496. See also Mandel, Long Waves of Capitalist Development: A Marxist Interpretation, 2nd rev ed. (London: Verso, 1994), 37–38, 119–20. |

| ↑9 | Figure from “Trade Union Bill: Ministers deny ‘attack on workers’ rights,’” BBC News, July 16th, 2015. |

| ↑10 | For further thoughts on Théorie communiste, see my “Now and Never,” in Communization and its Discontents, ed. Benjamin Noys (New York: Minor Compositions, 2011), 85–101. |

| ↑11 | For a lacerating critique of an influential variant of this discourse (namely Frank Wilderson’s afro-pessimism), as applied to Black Lives Matter, see Asad Haider, “Unity: Amiri Baraka and the Black Lives Matter Movements,” Lana Turner Journal 8 (2016). |

| ↑12 | An implicit normativity can also be detected in Clover’s almost exclusive attention to, for want of better terms, “emancipatory” (or anti-capitalist) rather than “reactionary” (or intra-working-class) riots. To remain with the principal focus of this article it would be worth reflecting on how the history of ‘hate strikes’ and (white) “race riots” inflects the periodization advanced in Riot.Strike.Riot. It’s worth noting that in both the U.S. and UK, there is a tight bond between race, class, and war, with some of the most severe riots involving the attempt of white workers to exclude racialized workers from certain job markets and occupations - during and after mass military mobilisation - often by attacking them and their families outside the workplace, in their neighborhoods and homes. We can consider here W.E.B. Du Bois’s crucial analysis of the 1917 East St Louis riots (“The Massacre of East St Louis,” The Crisis, September 1917), but also the enlightening account of riots against Yemeni, Somali and West Indian dockers in the wake of both world wars (in South Shields, Liverpool and Cardiff), in the chapters “Racism as Riot: 1919” and “Racism as Riot: 1948” in Peter Fryer, Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, 2nd ed (London: Pluto, 2010). Fryer’s chapter on the Notting Hill riots of 1958 does support, at least conjuncturally, a passage from racialized intra-working-class struggles around production to one around circulation and spheres of reproduction (principally housing), though in ways not wholly congruent with Clover’s narrative. |

| ↑13 | It would be interesting in this respect to revisit Paul Gilroy’s early efforts to link Birmingham cultural studies’ work on race, class and surplus populations (referenced by Clover in terms of Hall et al.’s Policing the Crisis) to a discussion of the significance of community and political autonomy. See “‘Steppin’ out of Babylon – Race, Class, and Autonomy,” in The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain, ed. Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (London: Hutchinson, 1982): “Localized struggles over education, racial violence and police practices continually reveal how black people have made use of notions of community to provide the axis along which to organize themselves. The concept of community is central to the view of class struggle presented here. It links distinct cultural and political traditions with a territorial dimension, to collective actions and consciousness within the relation of ‘economic patterns, political authority and uses of space’ [quoting Ira Katznelson]…The struggle to construct community in the face of domination makes Eurocentric conceptualizations of ‘the political’ or ‘the economic’ hazardous if not misguided” (286–87). |

| ↑14 | Furio Jesi, Spartakus: The Symbology of Revolt, trans. Alberto Toscano (Calcutta: Seagull, 2014), 53. This perspective interestingly resonates with Georges Didi-Huberman’s recent art-historical forays, based on Aby Warburg’s notion of pathos-formulae, into a gestural language of rage and revolt. See “Où va donc la colère?,” Le Monde diplomatique (May 2016), 14–15; see also Didi-Huberman’s recent talk at the Aby Warburg 150th anniversary conference: “Discharged Atlas: Uprising as ‘Pathosformel,’”June 15th, 2016. |

| ↑15 | Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1998), 487. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine