This review of Marvel’s Black Panther is part of a dossier on the political thought of Huey P. Newton. It contains spoilers.

In a sweeping survey of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s place in the liberal rhetoric of the most recent turn of the century, Pankaj Mishra points to Coates’s struggle with a disconcerting question: “Why do white people like what I write?” We might also ask why white people like the film Black Panther, which, according to the director Ryan Coogler, was inspired not only by Coates’s work on the Marvel comic books but also his writings on race and identity. At an event in Harlem’s Apollo Theater, Coates described the film as “Star Wars for black people,” rhapsodizing that the film was “an incredible achievement. I didn’t realize how much I needed the film, a hunger for a myth that [addressed] feeling separated and feeling reconnected.”

Indeed, like Star Wars, Black Panther presents us not with science fiction but with myth, sharing with it what we might describe as “semi-feudal futurism” – a term far more appropriate for this film than “Afrofuturism,” thrown around in the mainstream media stripped of any meaningful political context. Why do white people love Black Panther, just as they love Star Wars?

If we take a cynical look, we might conclude that it is because two classic modes of white racism are reproduced in Black Panther. First, the notion that the value of a culture and people lies in the extent of its technological development, a condition rendered as a natural property rather than one which results from an unequal global division of labor and distribution of wealth. Second, that the opposition of the oppressed to their oppressors amounts to nihilistic violence, practiced by criminals with unworthy intentions.

If we are more forgiving of the white audience – that is, assuming their condescending benevolence – we might conclude that the appeal of Black Panther lies not in the racist stereotypes it reinforces, but in the way it discredits the ideals of emancipation and egalitarianism and replaces them with privilege and philanthropy. Following Parliament-Funkadelic’s 1977 indictment, in the year of Star Wars, of the commercialization and containment of the radical potential of black music, let’s call this mythology “the placebo syndrome.”

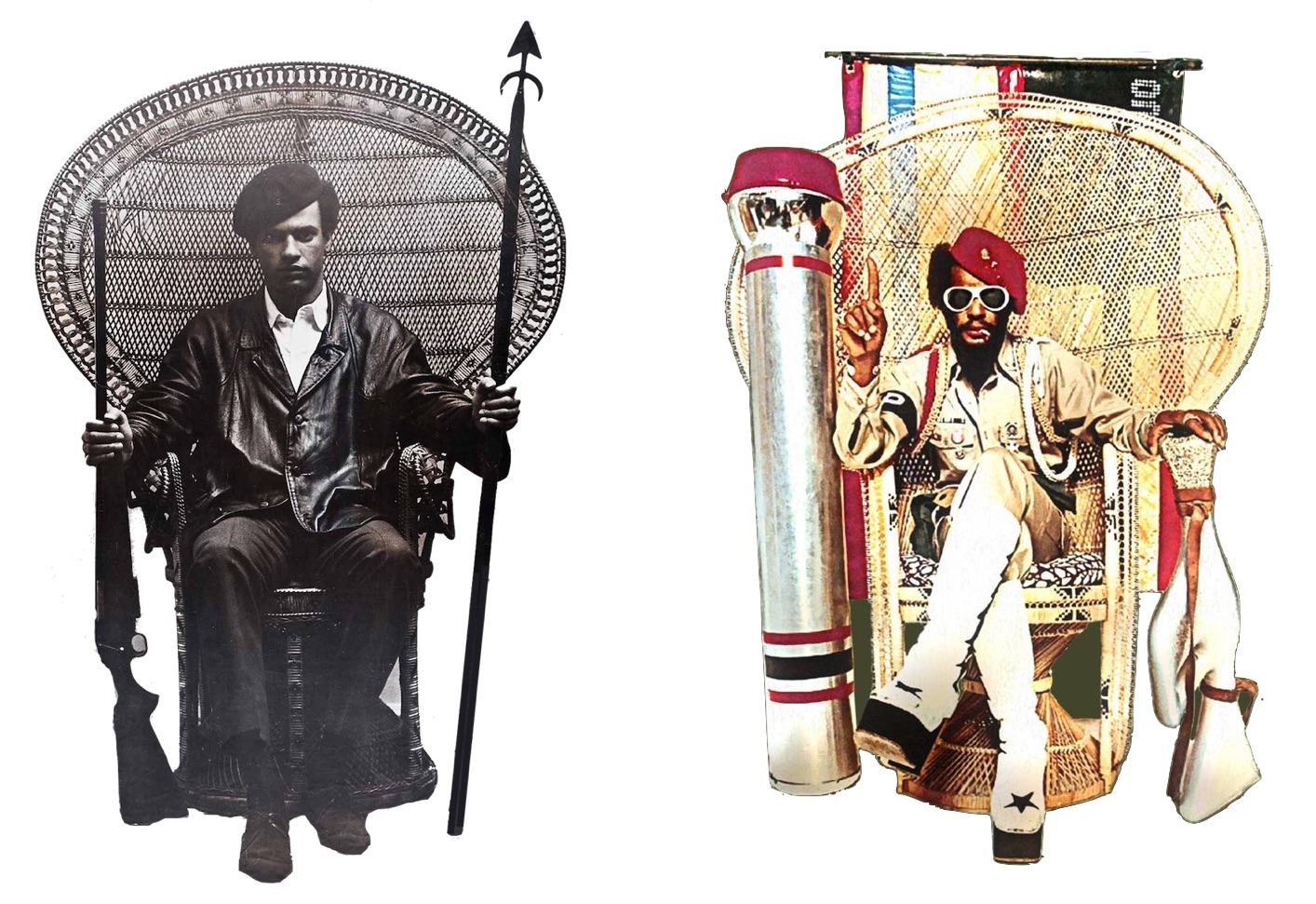

In the recent sequels, the semi-feudal futurism of Star Wars has been updated for an audience perhaps even less credulous of monarchies than it was in 1977, with Princess Leia converted into a general of a more or less republican anti-imperialist resistance. Black Panther is monarchist without apology. Its semi-feudal futurism is combined with the cultural nationalism historically associated not with the nominally connected Black Panther Party, but its adversary Ron Karenga’s US Organization – with which the Panthers had a violent shootout at UCLA leading to the deaths of Los Angeles Panther Captain Bunchy Carter and Deputy Minister John Huggins.

In Black Panther, we are presented with a mythology that makes anti-imperialist resistance unnecessary. In the Marvel myth of the African nation of Wakanda, initially created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby and brought to the big screen by Disney, Third World poverty is not a result of the ravages of colonialism and the uneven exploitation of global capitalism. Rather, this poverty simply does not exist – it is an illusion intended to hide the wealth cultivated and protected by an African monarchy from time immemorial. Development exceeding that of advanced capitalism has already been achieved within a semi-feudal mode of production protected in the boundaries of a nation-state.

Our hero is the monarch T’Challa, whose drug-induced physical strength allows him to function as an isolationist superhero, keeping Wakanda’s wealth hidden from the outside world. In this mission he relies equally on a dizzying array of advanced technological gadgetry, reminiscent of imperialist agent James Bond.

But the Wakandan monarchy has a dirty secret. T’Challa’s father T’Chaka murdered his brother N’Jobu, who while undercover in Oakland – the city where Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party in 1966 – had come to the conclusion that Wakanda’s advanced technology should be used to liberate black people around the world from poverty and oppression. Because this posed a threat to Wakanda’s national sovereignty, N’Jobu was eliminated and his son abandoned to grow up without his father.

N’Jobu’s son, Erik “Killmonger” Stevens, rises up with the goal not only of avenging his father’s murder, but also of claiming the Wakandan monarchy and using it to realize his father’s dream of international revolution. “Two billion people all over the world who look like us whose lives are much harder, and Wakanda has the tools to liberate them all,” he says to a skeptical Wakandan nobility. “Where was Wakanda?” These two political visions – of a global insurrection against oppression and the defense of the nation-state – are played out in the contest for the throne between the African monarch T’Challa and the urban African-American Killmonger, who the Wakandan nobility scorn as an “outsider.” As Christopher Lebron writes in Boston Review:

Rather than the enlightened radical, [Killmonger] comes across as the black thug from Oakland hell bent on killing for killing’s sake—indeed, his body is marked with a scar for every kill he has made. The abundant evidence of his efficacy does not establish Killmonger as a hero or villain so much as a receptacle for tropes of inner-city gangsterism.

T’Challa’s eventual victory against Killmonger is not achieved by African initiative alone, as the core figure of critical race theory Kimberlé Crenshaw has written. The visual spectacle of the film, Crenshaw reflects, “sucked me in like a narcotic and had me accepting things that made my heart ache upon reflection.” Its exuberant celebration of a purportedly timeless African essence represses its complicity with the history of racist violence. In Crenshaw’s words:

A civil war between Black families was unfolding over aiding other Black people, and… the CIA’s shooting down of vessels carrying technology into the fight against an anti-black world order was hailed as a heroic moment… I kept wondering how I’d come to dance on the table for the CIA? The ones that helped destroy the dream of African liberation, that had a hand in the assassination of Lumumba, staged a coup against Nkrumah, tipped off the arrest that imprisoned Mandela, installed the vicious, nation-destroying Mobutu? Why not throw in the FBI and COINTELPRO as kindly white characters? Was this meant to be ironic? What meaning do we assign the fact that the possibility of a real life Wakanda in the resource-rich Congo and Ghana, and the promise of a Pan African quest for collective self-determination were precisely the threats that the CIA worked to suppress?

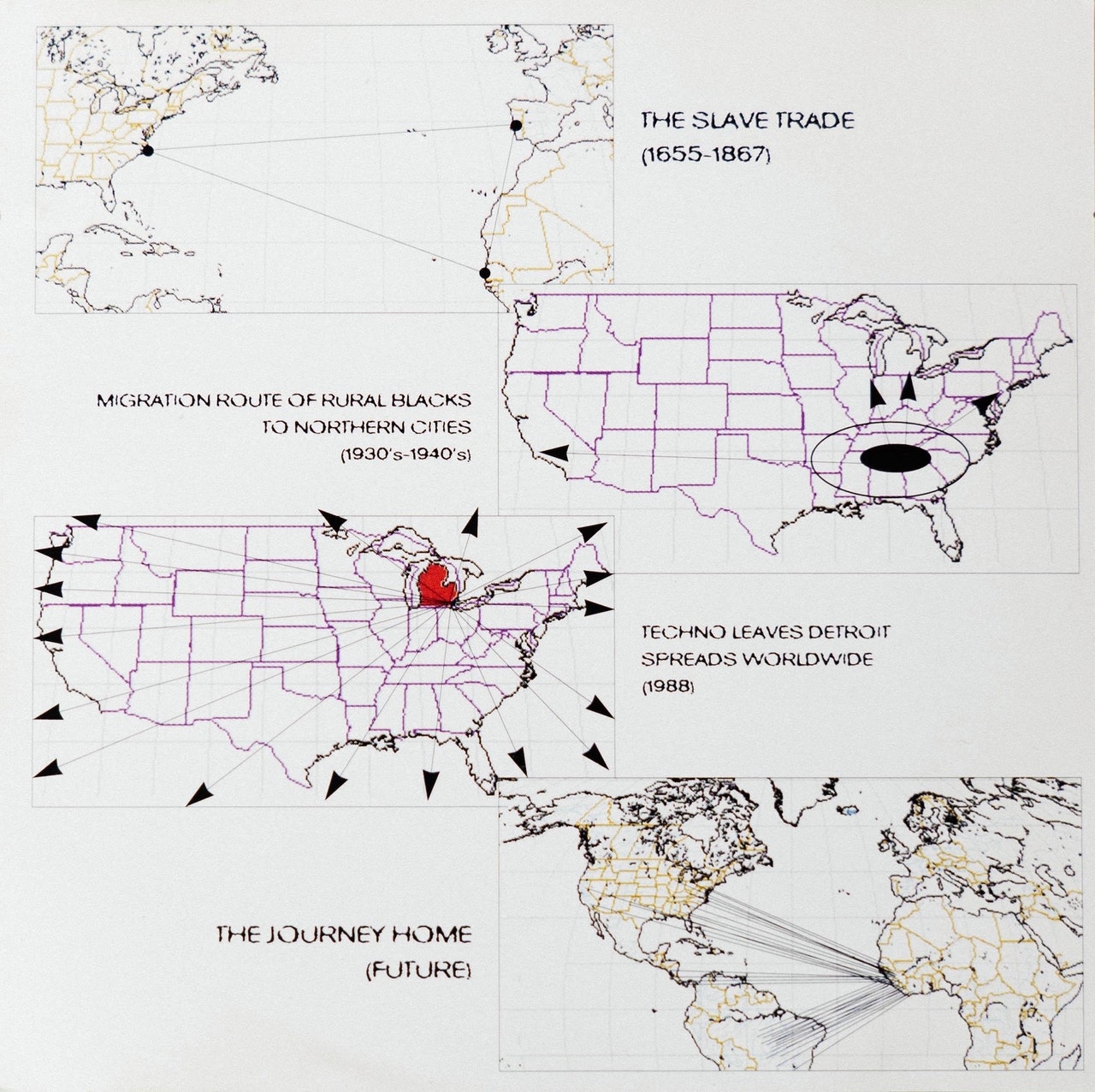

After Killmonger is murdered by T’Challa, he says, “Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ships, ‘cause they knew death was better than bondage.” But it is the lie told by Disney’s Black Panther that this is a binary choice. Killmonger’s last words are the closest the film gets to the actual historical contribution of Afrofuturism, in the negative form of a disavowal. The Afrofuturist Detroit techno group Drexciya proposed, in the liner notes to its 1997 The Quest:

During the greatest Holocaust the world has ever known, pregnant America-bound African slaves were thrown overboard by the thousands during labour for being sick and disruptive cargo. Is it possible that they could have given birth at sea to babies that never needed air? Are Drexciyans water-breathing aquatically mutated descendants of those unfortunate victims of human greed? Recent experiments have shown a premature human infant saved from certain death by breathing liquid oxygen through its underdeveloped lungs.

Drexciya’s Afrofuturist utopia builds on a concept introduced in Parliament’s follow-up to Funkentelechy Vs. The Placebo Syndrome, 1978’s Motor Booty Affair. On that album, George Clinton’s mythos moved from outer space to underwater, turning the myth of Atlantis into an alternative trajectory that begins with the North Atlantic slave trade. “We need to raise Atlantis from the bottom of the sea,” says the concluding track, “Deep.”

Achille Mbembe speaks of Black Panther as a futuristic fable, a “techno-narrative” whose power derives from its “reversal of the African sign,” recalling the diasporic “reflection on the possibility of a new world, of a black community which would be neither debased nor stamped with the seal of defilement.” The Afrofuturism of Black Panther, for Mbembe, is the overcoming of Western humanism from the vantage point of those who Western modernity assigned the space of the non-human. The future beyond Western humanism is prefigured by the coupling of the human body and the “quasi-infinite plasticity” of technology, and the concomitant transformation of the violated Earth of Africa into “astral material.”

However, from the vantage point of post-humanist Detroit, where the plasticity of technology subjected the diasporic black population to the tyranny of the automobile factory, Drexciya proposes an entirely different politics of Afrofuturism. Drexciyans do not belong to a counterfactual history insulated from the slave trade which lies at the foundation of capitalist modernity. Rather, they passed through it, and survived it, animating what Paul Gilroy called the “Black Atlantic.” Kodwo Eshun has described this diasporic continuum, in a powerful review of The Quest, as “the ‘webbed network’ between the US and Africa, Latin America and Europe, the UK and the Caribbean along which information, people, records, and enforced dematerialisation systems have been routing, rerouting and criss-crossing since slavery.”

The Drexciyan Afrofuturist myth is a myth not of the nation-state, but of liberation. As Eshun puts it: “By inventing another outcome for the Middle Passage, this sonic fiction opens a bifurcation in time which alters the present by feeding back through its audience – you, the landlocked mutant descendent of the Slave Trade.” It is a myth which, as Nettrice R. Gaskins writes, “draws on modern African cultural ethos, technology, and artistic actuation by creating self-determined, representational worlds. In discourse of dissent, this is a place where the oppressed plot their liberation, where stolen or abandoned migrants survive adverse conditions.”

The film is aware of the greater power of the myth of this revolutionary Black Atlantis – and it recognizes that Killmonger, for so many viewers, will be its most sympathetic character. Thus T’Challa must somehow absorb Killmonger’s spirit of resistance and justice to bring the film to a palatable conclusion. He does so by reproducing the political placebo syndrome that came about in the late 20th century. Under his rule, Wakanda begins practicing the black capitalism that came to displace black power as the revolutionary movements of the 1960s and 1970s were crushed by the state and ran up against their own strategic and organizational deadlocks. He buys the condemned building where his uncle was murdered and establishes a center for STEM education – an investment of the Wakandan monarchy in urban development.

The character of the Black Panther was introduced in the Fantastic Four comic series three months before the founding of the Black Panther Party, but the name-recognition and credibility of the film in a political landscape marked by Black Lives Matter surely draws on the history of black liberation for which the BPP is such a powerful synecdoche. In her review of the film at The Baffler, Kaila Philo has noted precedents to its appropriations of BPP history and aesthetics, by cultural icons like Jay-Z and Beyoncé:

Black artists revere the Black Panthers because they have given us our most indelible images of Black radicalism and, more importantly, power; the Party’s staunch socialist and anti-imperialist ideology often falls to the wayside, however, because the power they seek is economic and not merely a function of the white capitalist credo, which leaves the poor behind. It’s this credo that quietly informs our best and brightest Black entertainers to this day.

In a 1970 letter to the National Liberation Front of Vietnam, founder of the Black Panther Party Huey P. Newton wrote, “we are interested in the people of any territory where the crack of the oppressor’s whip may be heard. We have the historical obligation to take the concept of internationalism to its final conclusion – the destruction of statehood itself.” With this revolutionary agenda suppressed and dismissed by today’s multicultural liberalism, Killmonger’s mission can only be, as Adam Serwer writes disingenuously in The Atlantic, the production of a new historical trauma, on the model of X-Men’s Magneto:

Killmonger’s plan for “black liberation,” arming insurgencies all over the world, is an American policy that has backfired and led to unforeseen disasters perhaps every single time it has been deployed; it is somewhat bizarre to see people endorse a comic-book version of George W. Bush’s foreign policy and sign up for the Project for the New Wakandan Century as long as the words “black liberation” are used instead of “democracy promotion.”

Arming insurgencies all over the world, however, was a project of internationalist revolutionaries long before George W. Bush, as Newton’s letter attests, and it is diametrically opposed to the violent entrenchment of nation-states in the existing imperial hierarchy represented by American neoconservatism. Revolutionary internationalism presents an alternative to the placebo syndrome of capitalist philanthropy, to which the liberal multicultural elite claims there is no alternative. Disney asks us which figure is worthy of the title of Black Panther: is it the poor African-American child from Oakland who dreams of international revolution, or the monarch who aims at defending the glory of his nation? History has already given us the answer.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine