Fortunately, an idol of my pantheon was and remains Rosa Luxemburg, as intrepid a lover as she was a revolutionary. Amorous passion and revolution merged within her through the figure of Leo Jogiches. She also demonstrated that politics is not asceticism or shamelessness, both instruments of its discredit.

A climate of forgetting reigns over our century. We honor obsolescence. The city in which we live has declared itself eternal. Everyone, with the greatest comfort, measures their stature through its deployed newspaper. We notoriously refer to a single game: our democracy is the best of all possible systems. This is “almost” what Luxemburg thought; proletarian democracy is not the best of all possible regimes, but that which no one has experienced. How to speak about revolutionaries when revolution no longer exists? Are they mere offerings to the execration of memory, these splendid men and women?

They embodied such bravery and so many qualities of spirit. On the eve of her death, in a small apartment in a neighborhood of Berlin, where she and Karl Liebknecht were hiding, Luxemburg wrote the following:

“Order prevails in Warsaw!” declared Minister Sebastiani to the Paris Chamber of Deputies in 1831, when after having stormed the suburb of Praga, Paskevich’s marauding troops invaded the Polish capital to begin their butchery of the rebels. “Order prevails in Berlin!” So proclaims the bourgeois press triumphantly, so proclaim Ebert and Noske, and the officers of the “victorious troops,” who are being cheered by the petty-bourgeois mob in Berlin waving handkerchiefs and shouting “Hurrah!” … “Order prevails in Warsaw!” “Order prevails in Paris!” “Order prevails in Berlin!” … You foolish lackeys! Your “order” is built on sand. Tomorrow the revolution will “rise up again, clashing its weapons,” and to your horror it will proclaim with trumpets blazing: I was, I am, I shall be!1

These words encompassed Rosa Luxemburg’s presence on earth. The day after, she was killed by a bullet to the head fired by a Freikorps soldier, a paramilitary organization commanded by the socialist defense expert, Noske. Noske had declared shortly before: “somebody has to be the bloodhound.”

In the same last piece of writing, her purported testament, Rosa wrote:

Was the ultimate victory of the revolutionary proletariat to be expected in this conflict? Could we have expected the overthrow of Ebert-Scheidemann and the establishment of a socialist dictatorship? Certainly not, if we carefully consider all the variables that weigh upon the question. The weak link in the revolutionary cause is the political immaturity of the masses of soldiers, who still allow their officers to misuse them, against the people, for counterrevolutionary ends. This alone shows that no lasting revolutionary victory was possible at this juncture. On the other hand, the immaturity of the military is itself a symptom of the general immaturity of the German revolution.

It was January 14, 1919. Rosa and Liebknecht were assassinated on the 15th. With them, Germany died, another Germany. What was living? One trait at least:

Because the suprema ratio [supreme principle] with which I have succeeded in all my Polish-German revolutionary practical work is this: always to be myself.2

Myself. Along the lines of a continuously regenerated creative power, Rosa Luxemburg practiced the incessant coming-and-going from self-to-self, the back-and-forth of actions, polemics, and thoughts: in order to begin again. Rosa was Polish, thereby Russian (Poland being annexed by the Tsarist empire), and agitated in Germany and Poland. Her Polish was as good as her German and Russian, and she read French, English, and Italian. She was always accused of being foreign. And if in Switzerland, where she did her studies of political economy and the natural sciences, or even in Poland where her family lived, she was never made to feel it, in Germany she was also reminded that she was Jewish.

Upon her exit from secondary school, she was influenced by socialist ideas, connected with Marcin Kasprza, a revolutionary worker who created an extensive number of groups and whose impact on Rosa’s spirit was significant.

She left for Zurich, carrying out brilliant studies first in the natural sciences then in economics. Zurich was full of revolutionary immigrants and was also heavily Polish…

There formed a group, a mental means of being. Not consenting to any kind of inferiority, it was called the “peer group.” It consisted of Rosa, Adolf Warszawski, Feliks Dzierzynski, Cesaryna Wojnarowska, and Leo Jogiches. The crucial encounter with Jogiches will last for the rest of her life.

This woman loved – as far as we know, excluding rumors – three men: the great unsung Leo Jogiches, an unknown, and a son: that of Clara Zetkin. Made of an elective instinct, she refused to see a lack of proportion between her many activities.

Leo Jogiches is a profound figure in what one might call political interiority. A great organizer, a kind of non-Bolshevik Bolshevik (he never agreed with Lenin), never wanting to appear, acting behind the scenes, he was the champion in clandestinity. He loved Rosa and a sort of withdrawn freedom [liberté reculée]. It was this withdrawn freedom (along with the fact that he did not write) that gave an invisibility to his personage in which we find him. This freedom and the casualness stemming from an absolute dedication to politics meant, perhaps, that they did not live together, despite Rosa’s supplications. For Jogiches, being a revolutionary provided a different meaning to the glory of living. A hundred years later, he would have been accused of being one of those aristocrats of revolution. He was very rich, secretive, elegant, extremely courageous, austere, obstinate, a friend of bootleggers and all those people working underground to whom he belonged and whose art he possessed. Politics alone mattered to him, which included Rosa, such was the spirit of the group. Leo used his wealth, financed newspapers, supported Rosa, flirtatious and keen on trivial pleasures, bought her clothes. Concerned about her appearance, she wrote to him: which hat would be appropriate for the meeting I am going to speak at tomorrow? He was Jewish and indifferent to the fact of being so. He inspired and taught Rosa. When she wrote, having had lengthy discussions with him, she asked him forgiveness for employing his ideas so indiscreetly. When Rosa and Liebknecht were assassinated, he became the head of the German Communist Party.

He hailed from Vilna, Vilnius, which had become a working-class and Jewish center following the atrocious pogroms, specifically in 1860, that pushed Jews from the countryside to find refuge in the city and proletarianize themselves. Jogiches began to organize them at age 18. Though he did not speak Russian, he learned Yiddish during this time.

From Zurich, they played the general part. They founded the party of Poland, The Workers’ Cause, the newspaper that Rosa edited and would go print in Paris. She wrote all the articles and signed them under different names. This would last until 1898.

She connected with August Bebel, Paul Singer, Franz Mehring, and others. She entered into the major newspapers of the Social-Democratic Party. She became famous through her writings, attacked Bernstein and then Kautsky, wrote Reform or Revolution?, whose title basically said everything. In 1899, she took up cudgels against parliamentarism. In 1904, at the International Socialist Congress in Amsterdam, Jaurès sharply attacked her, while she translated the speech against her with brio and precision!

Then there was 1905. Russian Poland rose up, as an echo of Russia. Leo left for Poland. She joined him during the general strike of 1905, publishing The Red Banner, organ of the Polish Social-Democratic Party. They were arrested together; she was soon released on a 2000 ruble payment by her brother; Leo was sentenced to 8 years hard labor, but escaped. She wrote The Mass Strike, the Political Party, and the Trade Unions in which she contrasted the mass strike with the general strike and the insurrectional strike with the vote. Together, with Liebknecht, they founded the Spartacus League in 1915. She was imprisoned several times, once for “insulting the emperor,” and left as calm as she had entered. Luxemburg – so small in stature that she needed cushions to raise herself up – wrote The Russian Revolution after the Russian Revolution of 1917, which she and Jogiches were nearly the only ones to approve of and defend in the German political milieu. She wrote:

It is a well-known and indisputable fact that without a free and untrammeled press, without the unlimited right of association and assemblage, the rule of the broad masses of the people is entirely unthinkable.3

For Luxemburg, freedom was the “life element” of proletarian dictatorship.

Lenin wrote One Step Forward, Two Steps Back; she wrote a criticism of it. The polemic with him commenced. In 1914, she fought against socialists’ support of the war, against the Sacred Union, and spent a year in prison for denouncing Prussian training and corruption among officers.4 In 1915, in prison, she wrote the Junius Pamphlet.

Such was Rosa’s arrow, up until the target that murder imposed. She loved life and revolutionary politics and Jogiches so passionately and so equally that the scandal, immense for all, though representative, which ensued is unrelated [hors rapport]: exhibiting both loves, in an imperturbable foreground, makes her a rare and strangely modern figure. Rosa is not a bloc, a ghoul, the one whom enemies dubbed “the quarrelsome female.” She had two muses, the muse of happiness and that of revolution. With Rosa Luxemburg, the mystery cannot be limited.

To Leo Jogiches, she sent letters giving new words against routine love, linked without contrast to comprehensive political reports and discussions: against Bernstein; against Kautsky; what about Lenin? What tactics in German social democracy? The tasks regarding their organization, the Social-Democratic party of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania. And “my love, my only, my dearest.” The letters were like her life: what do you think of buying this spring jacket?5

Her personal note was the notion of “mass.”

She did not believe in the objective situation. Only personal or subjective force counted. The masses were the name of revolutionary thought.

Against the background of the revolt against the war, in 1918, workers’ and soldiers’ councils emerged, deposed the emperor. A republic of Germany was proclaimed, and another, the republic of Liebknecht and Rosa, the same day. The social-democratic party took power. Ebert, one of its leaders, declared that it was necessary to eliminate the dauntless Spartacists. The Freikorps, legion against Bolshevism and paramilitary wing inherited by Nazism, led by the socialist minister Noske, were created. In Berlin, a fraction of socialists, the independents, wanted to take power against the majority socialists in government. The Berlin Commune began.

“The Spartacus League refuses to participate in governmental power.”

“The Spartacus League will also refuse to enter the government.”

“The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power except in response to the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian mass,” she wrote.6

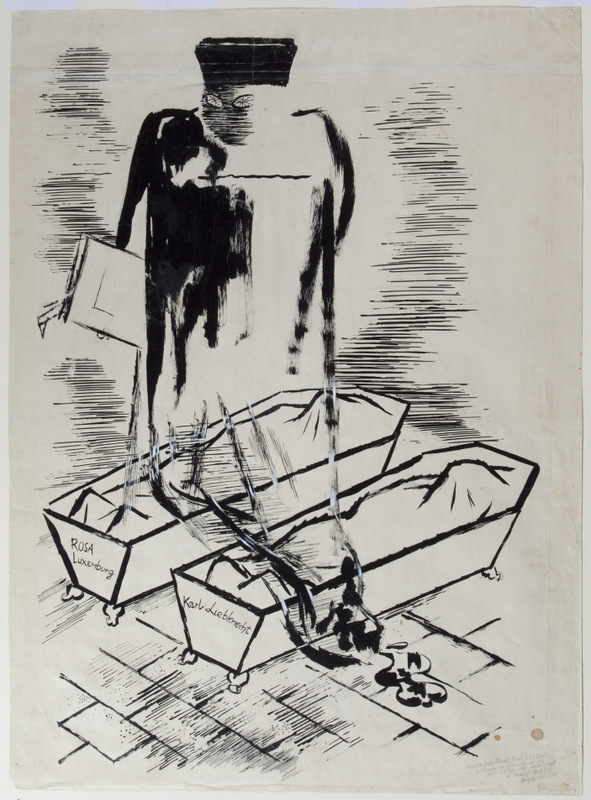

Rosa, leaving prison, opposed the insurrection and supported it since it had been set off. The Freikorps pursued her. There was a price on Rosa and Liebknecht’s heads. They changed dwellings every night. January 12 and 13, they stayed in a workers’ apartment in the Neukölln neighborhood, the next day, in a bourgeois apartment in Wilmersdorf. There they wrote their last text. January 15, at 9pm, the soldiers came in. Rosa, who had a migraine, was lying down. She had a small suitcase, some books, an optimistic last move. They were taken to a hotel. The Eden Hotel. They forced Rosa to the first floor where she was interrogated by Captain Pabst. The hussar Runge was charged with the murder. He stood at an entrance at the side of the hotel and hit her with a rifle butt on the head. She was thrown to the ground and dragged into a car. There, it was finished with a bullet in the temple. Her body, thrown in the Landwehrkanal. Liebknecht was murdered the same day close to the Eden Hotel.

With Rosa Luxemburg dead, Jogiches who all his life had been an expert clandestine stopped hiding. He sent a telegram to Lenin, with whom he had never gotten along: “Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht have carried out their ultimate revolutionary duty.” To Radek, who told him to flee: “Somebody has to stay, at least to write all our epitaphs.” When he had safely put away what remained of Rosa’s manuscripts, he tried to track down her murderers, wandering Berlin, and was captured and killed, with a bullet in the back, by a policeman.

The murderers of Rosa and Liebknecht were tried. The hussar Runge was sentenced to two years and two weeks for “attempted murder”; Lieutenant Vogel, officer on duty when Rosa perished, received four months for failing to report a corpse and illegally disposing of it.

– Translated by Asad Haider and Patrick King

This text is an excerpt from Natacha Michel, Le roman de la politique (Paris: La Fabrique, 2020), 164-74. A version originally appeared in Lettres sur tous les sujets, no. 6, supplement to Le Perroquet (November 1992): 4-12. Our thanks to La Fabrique éditions for their generosity in authorizing the translation.

References

| ↑1 | Translators’ Note: See Rosa Luxemburg, “Order Prevails in Berlin,” January 1919. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | TN: See Rosa Luxemburg, “To Leo Jogiches, May 1, 1899,” in The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg, ed. Georg Adler, Peter Hudis, and Annelies Laschitza, trans. George Shriver (London: Verso, 2011). |

| ↑3 | TN: See Rosa Luxemburg, The Russian Revolution, trans. Bertram Wolfe (New York: Workers Age Publishers, 1940), Chapter 5. |

| ↑4 | TN: For further details see J.P. Nettl, Rosa Luxemburg, Vol. 2 (London: Oxforward University Press, 1966), 484-92. |

| ↑5 | TN: See Rosa Luxemburg, Comrade and Lover: Rosa Luxemburg’s Letters to Leo Jogiches, ed. and trans. Elzbieta Ettinger (London: Pluto Press, 1981). |

| ↑6 | TN: Rosa Luxemburg, “What Does the Spartacus League Want?,” December 1918. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine