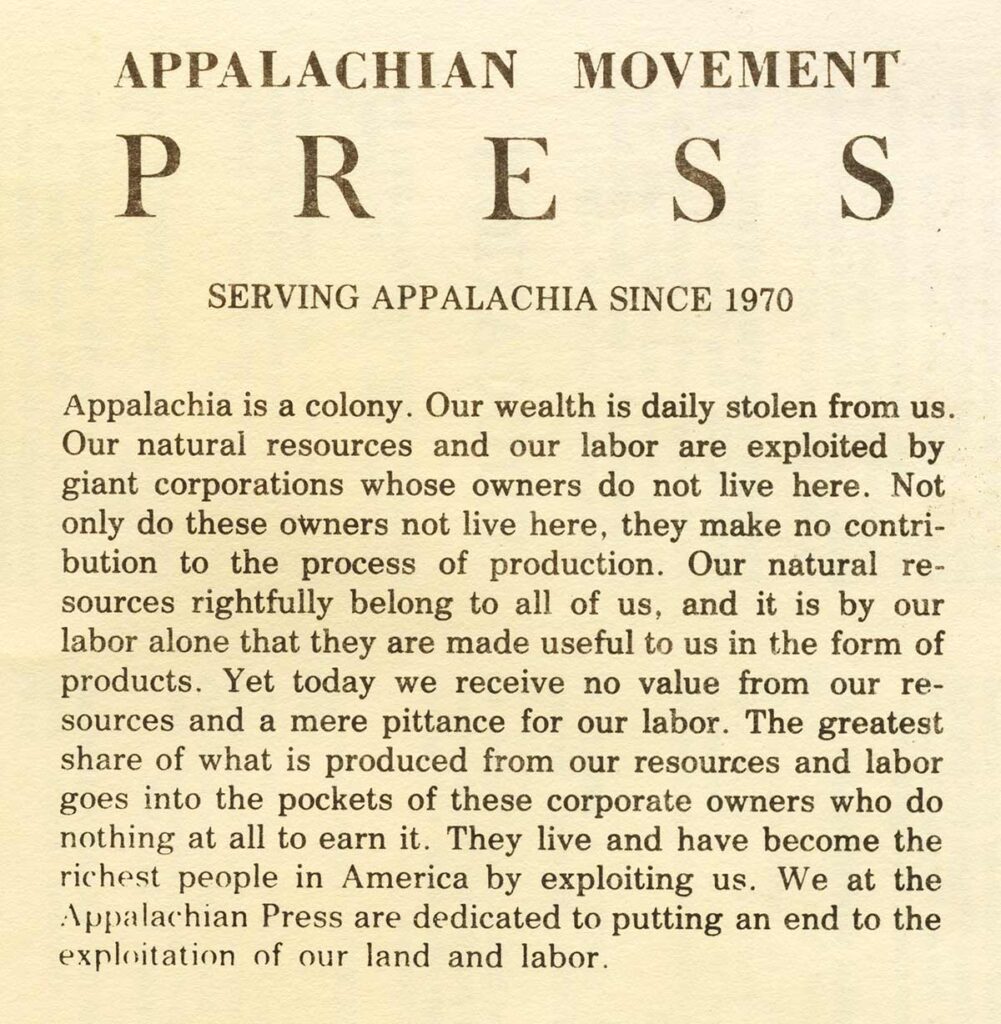

Throughout 2018-19, in the course of my research for the book So Much To Be Angry About, I interviewed over a dozen people who were involved in the Appalachian Movement Press (AMP) printshop. The book weaves together memories and documents of AMP, and in my interviews I often asked about the overall politics that formed the foundation of the group. Was there a unified motivating ideology, an agreement held among them beyond the need to “get full information out to all Appalachians”?1 The answers I got were usually circumspect, but many pointed me back to the AMP mission statement as a guiding principle which, though strident in tone (and a bit stilted), defined their mission as no less than the full liberation of the Appalachian colony. The statement reads:

Based in Huntington, West Virginia throughout the 1970s, Appalachian Movement Press was born out of militant student organizing at Marshall University, a college that historically draws students from the rural coalfields of Central Appalachia.2 Most of the well-documented movement printshops in the US during this era were based in large cities, creating publications in an urban context and often for a national readership.3 AMP, however, was formed in a small city and defined a specific regional, class-conscious, and largely rural audience and focus. In this era, if you wanted to start an activist newspaper or print anti-war flyers for an upcoming demonstration, you needed to know a printer that was sympathetic to your politics (or at least willing to take your money and not ask questions). Otherwise, you needed to start your own printshop: this is how the “movement” press was born. The AMP operators got started by pulling together an assortment of second-hand printing and binding equipment from around Huntington and running their first publications out of the front living room of a collective house near the college.

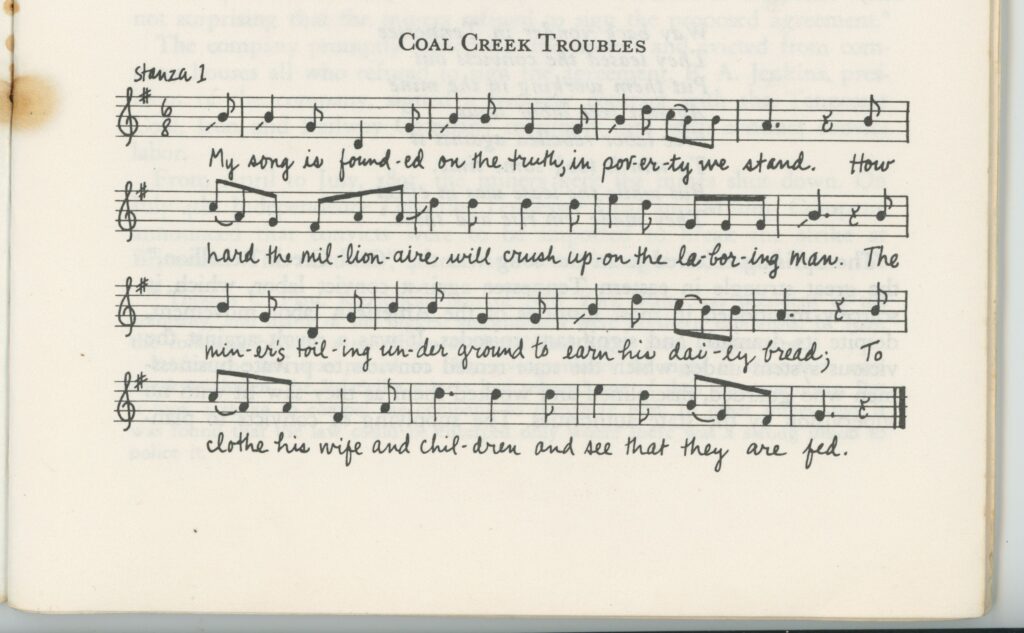

AMP eventually positioned themselves to run print jobs at cut-rate pricing for a growing network that included activists involved in actions against strip mining, rank-and-file coal miners battling corruption in the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) union, community organizers working around (or splintering from) federal War on Poverty initiatives, citizens and workers fighting for recognition and treatment of black lung disease, and a myriad of other struggles.4) Besides this gig-work in the movement, AMP workers also printed regionally focused magazines at rates which kept their shop, and these publications, viable on their shoestring budgets.5 While they never set out to mark their own legacy, probably the most identifiable facet of the history of AMP output is their in-house imprint: several dozen staple-bound titles bearing their sparse logo of a coal miner’s pick-ax. Songbooks, reprints of labor history articles and book chapters that were otherwise difficult for their audience to find, contemporary anti-corruption journalism, original chapbooks by firebrand Communist activist/organizer/educator/poet/preacher Don West, and anything else they thought their readership needed to “educate themselves for the coming conflicts.”6

***

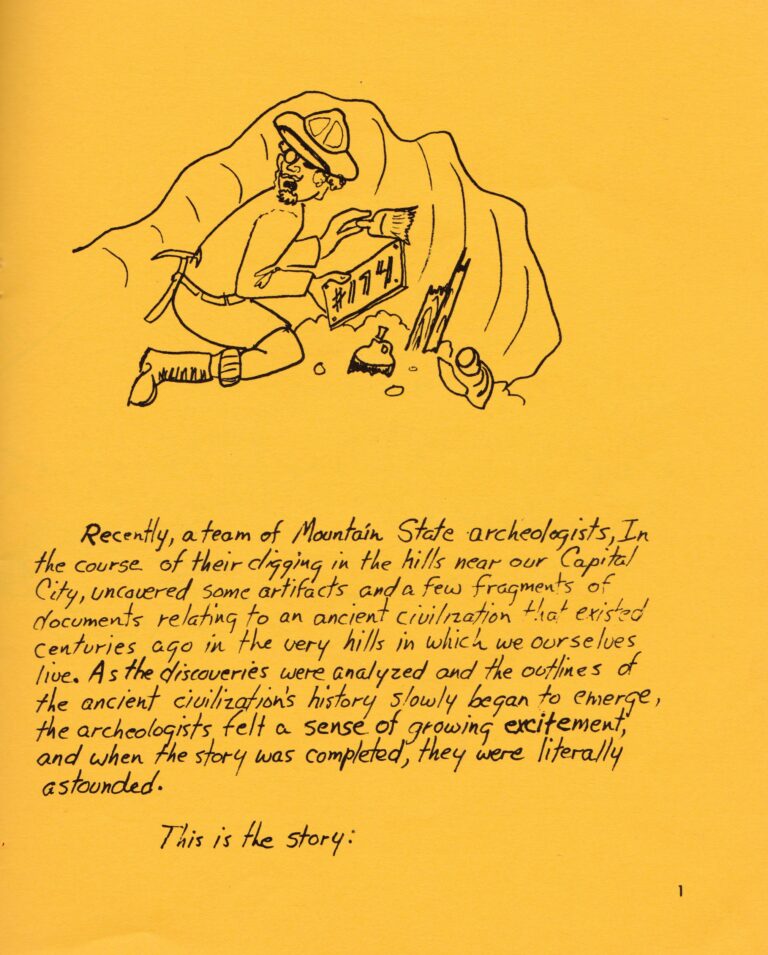

Sometime in the early 1970s, during AMP’s first big wave of printed output, Rod Harless produced The Hillbillys: A Book for Children at the AMP printshop. The story was lettered and illustrated by artist Dan Cutler, but unfortunately his work had not surfaced in my research by the time So Much To Be Angry About hit the presses. I did have some context for Harless, who had published with AMP before: a former Navy budget analyst at the Pentagon, Harless later worked for a regional housing authority and taught at Antioch College’s brief and magnetic Appalachian Campus in Beckley, WV.7 Most of what AMP produced was heavy on the text and thin on any graphics, so when I finally found a copy of The Hillbillys in an archive, I was excited to find that it was illustrated. I sat right down on the floor between the library stacks, cross-legged like I was a kid again, reading it cover to cover.

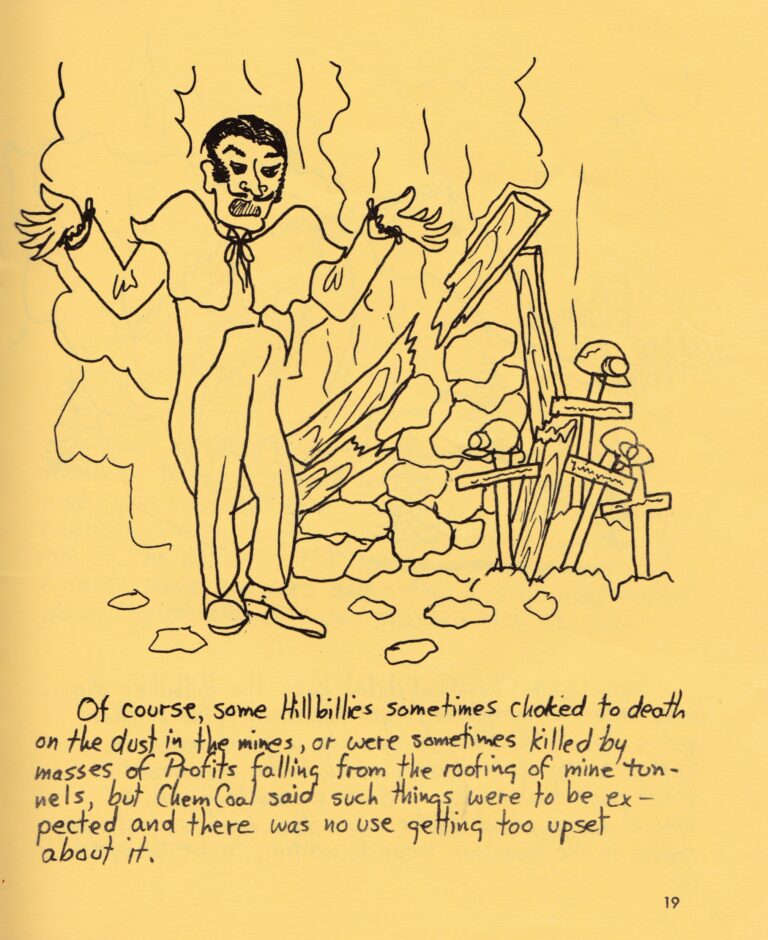

The Hillbillys (sic) is hardly a children’s book. The illustrations are raw, and it is a bleak story that carries a pessimistic despondency rare to see from movement documents in the era. Harless and Cutler offer a deeply frustrated parable of exploitation and environmental destruction in the Appalachian region. They take a stark view of prior generations’ inability to effectively counter the coal companies who had already wrought human rights abuses across the region for decades and were, by the 1970s, seriously ramping up the practice of strip mining. But The Hillbillys isn’t just a work of dark humor. The book serves as an offbeat, pedagogical outline of the Appalachia-as-resource-colony idea, the core politics that Appalachian Movement Press proclaimed in their mission of liberation.

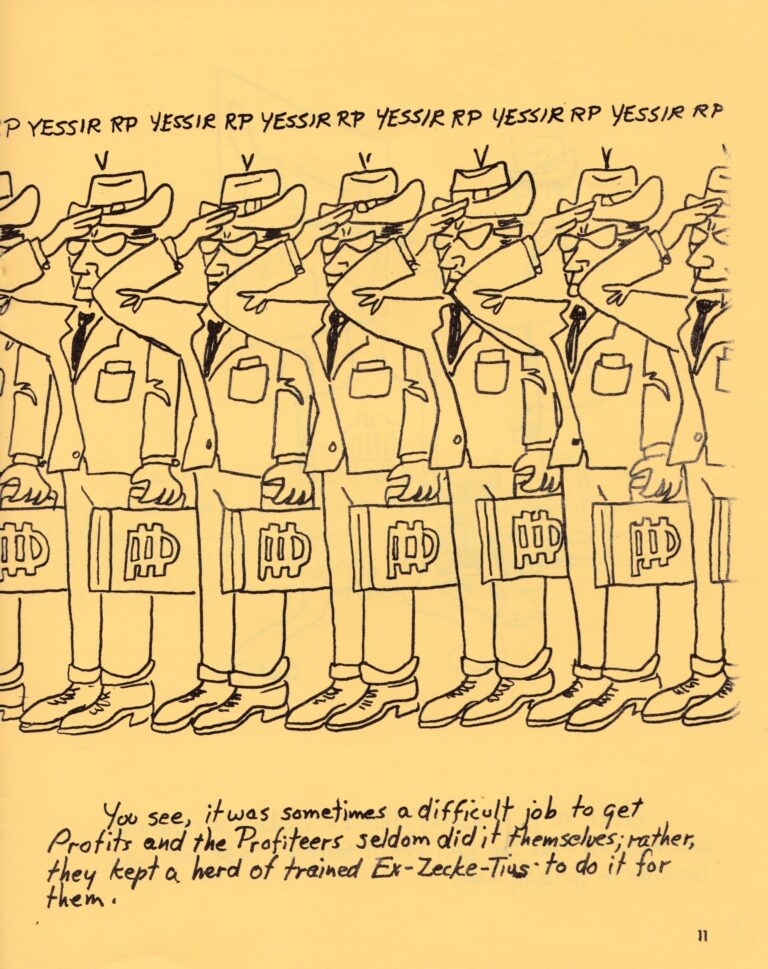

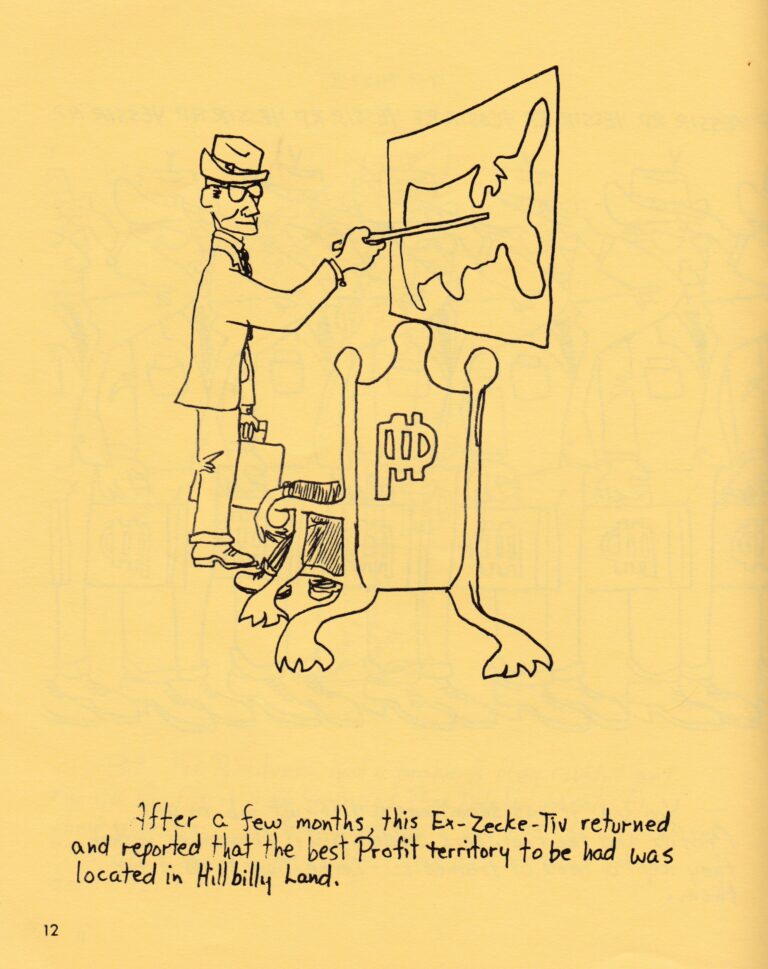

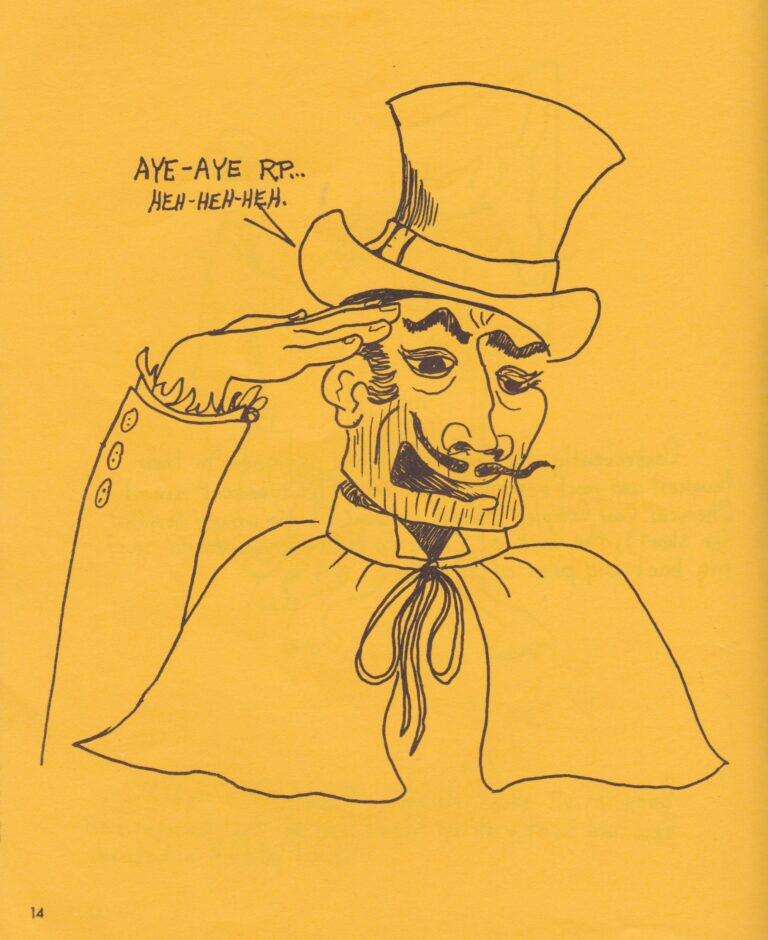

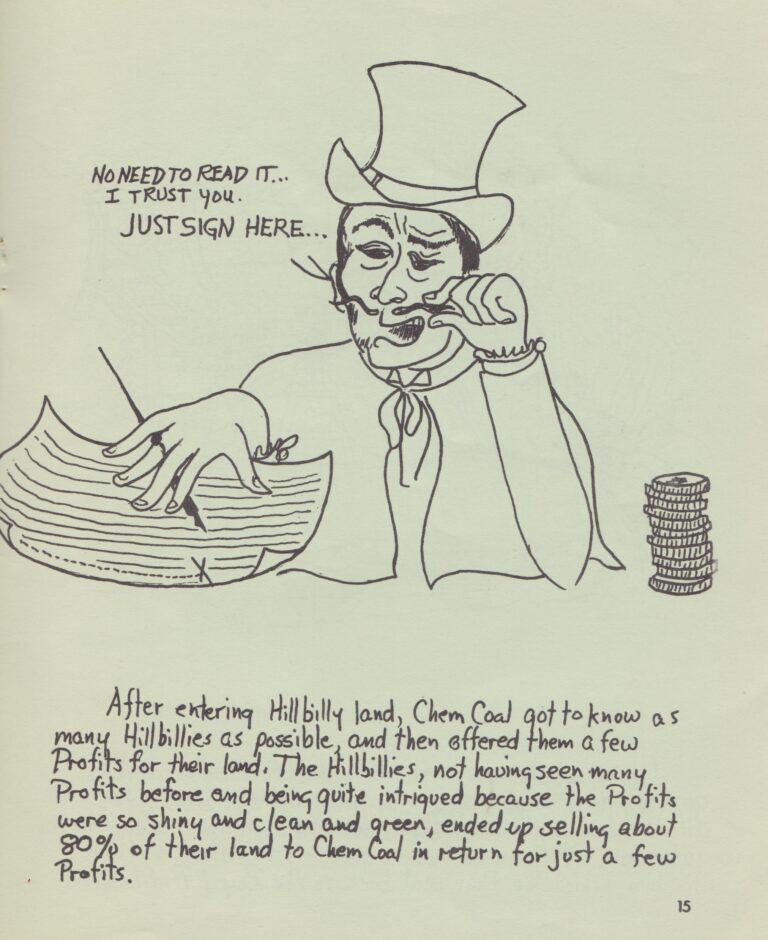

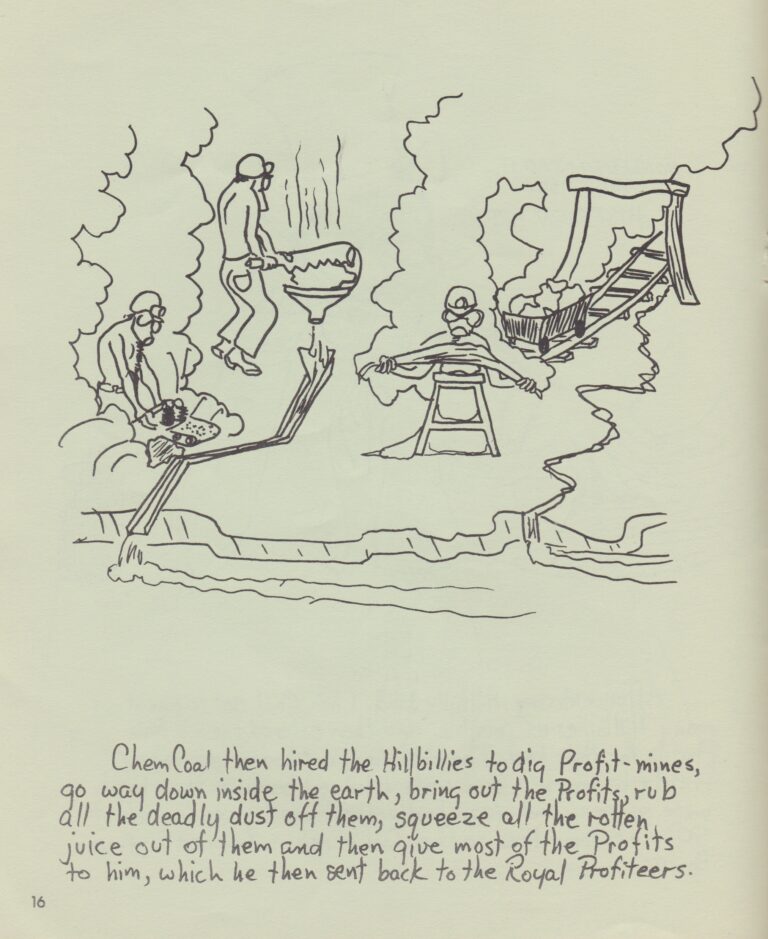

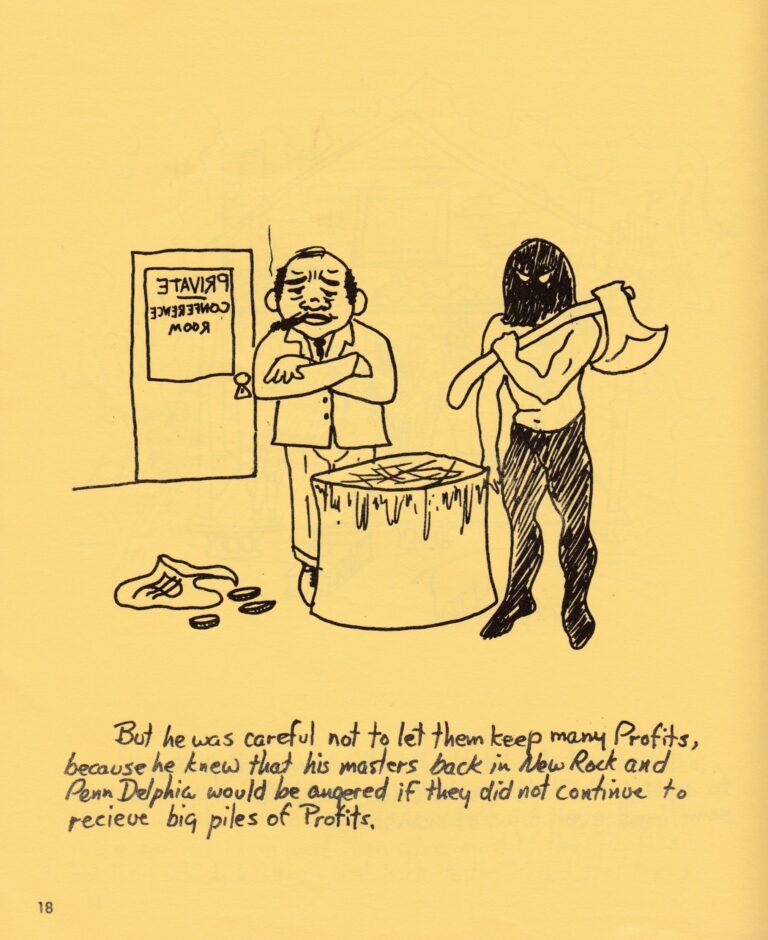

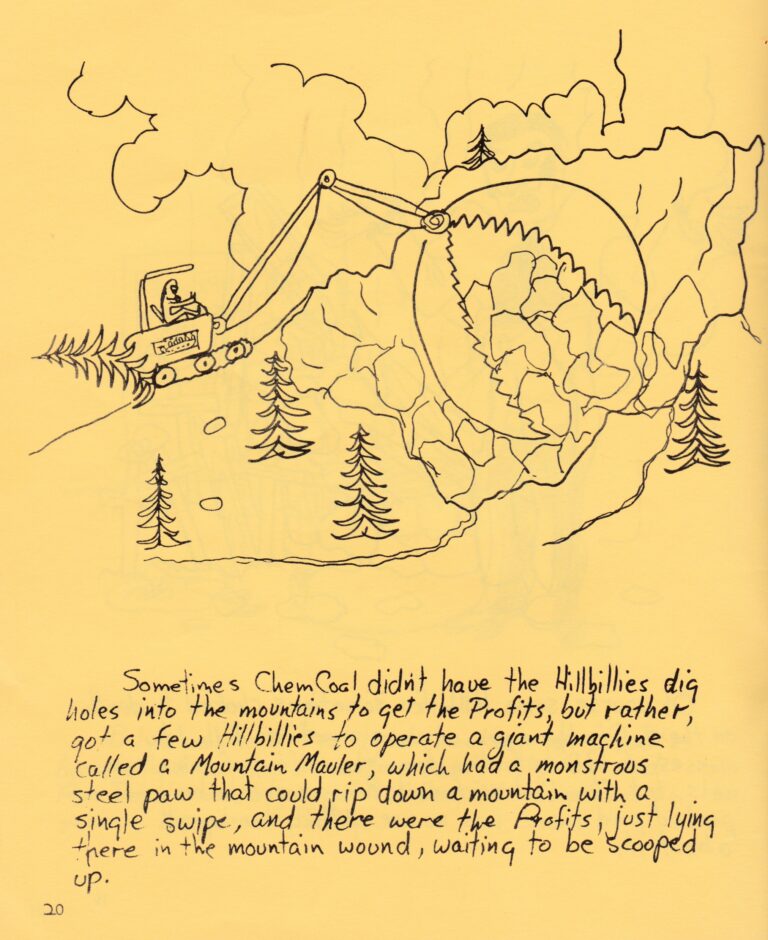

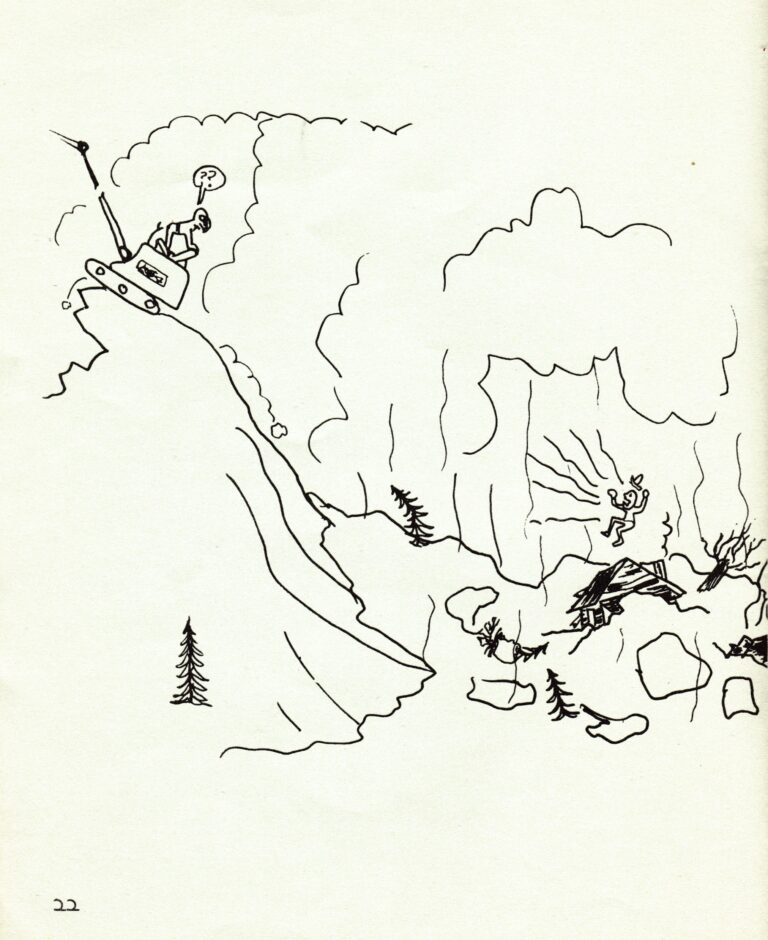

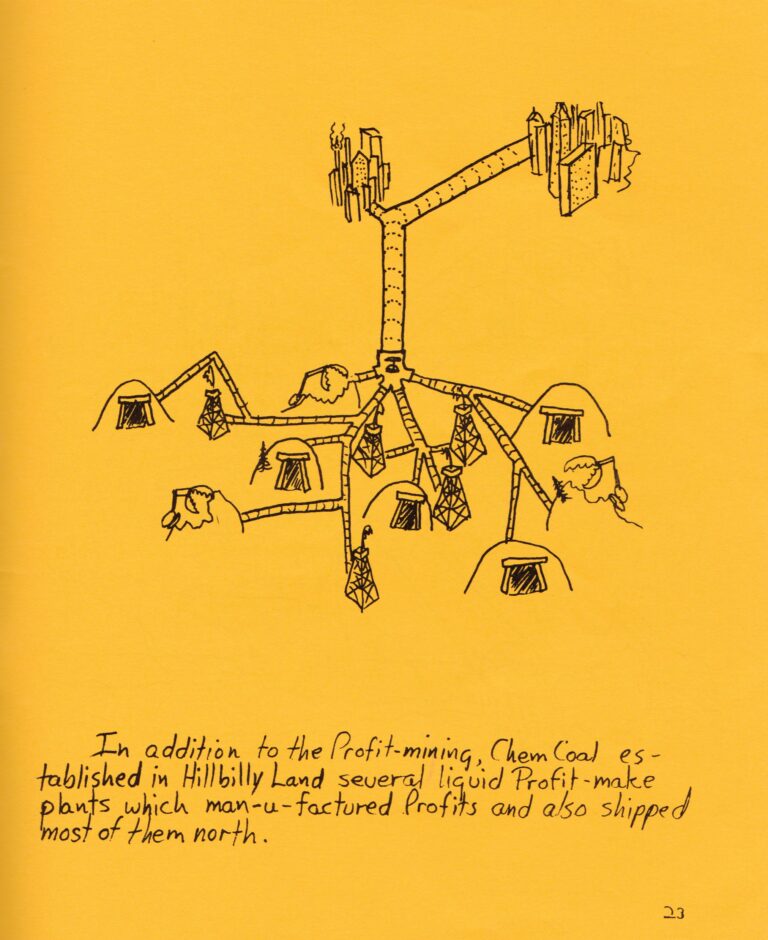

The thirty-eight illustrated pages of The Hillbillys tell a story of “an ancient mountain kingdom called Hillbilly Land.” Hailing from the faraway lands of New Rock and Penn Delphia, a ruling-class “order of men called Royal Profiteers,” who have an insatiable appetite for eating thin green chips called “Profits,” learn from their “Ex-Zecke-Tivs” that Hillbilly Land sits on an underground trove of Profits. Since these Profits are mined underground and must undergo complicated processing before being eaten, it’s going to be a hard sell to convince the Hillbillies to destroy their homeplace in the pursuit of digging this addictive resource out of the ground. But the Royal Profiteers send their “toughest and most resourceful” Ex-Zecke-Tiv to do business on their behalf, and pretty soon the Hillbillies are strip mining their homeplace, operating scoops and draglines and arguing amongst themselves, wrecking the land while Profits are shipped right out of the mountains daily.

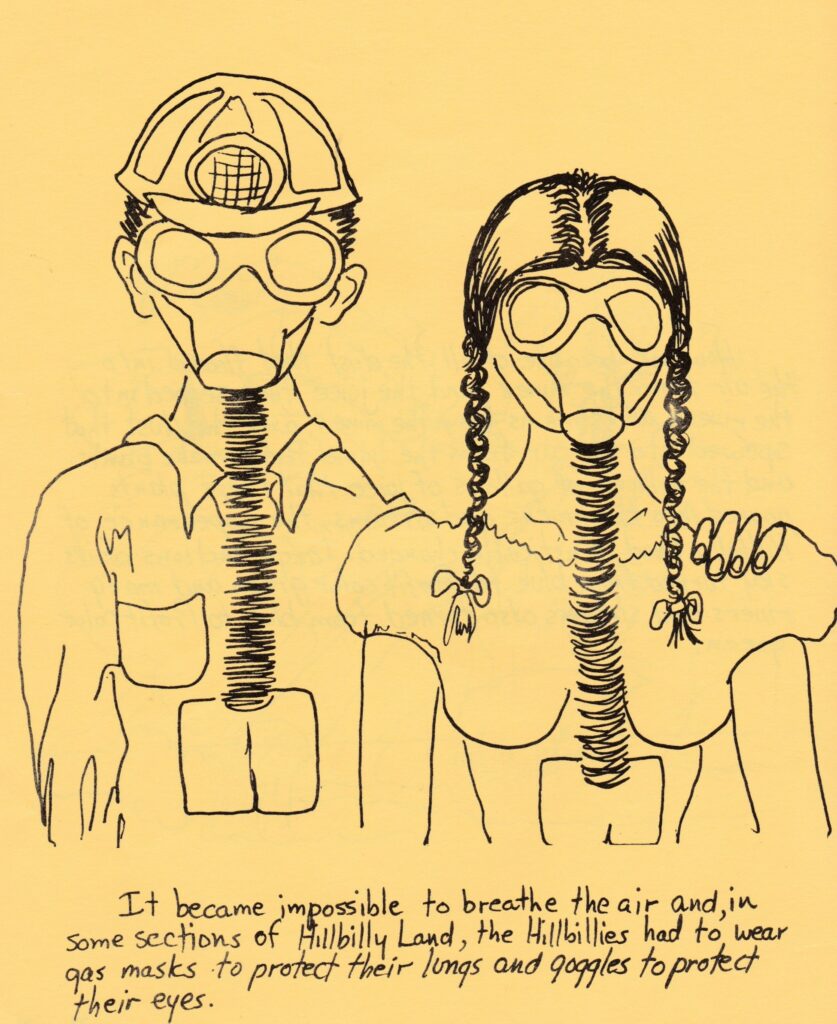

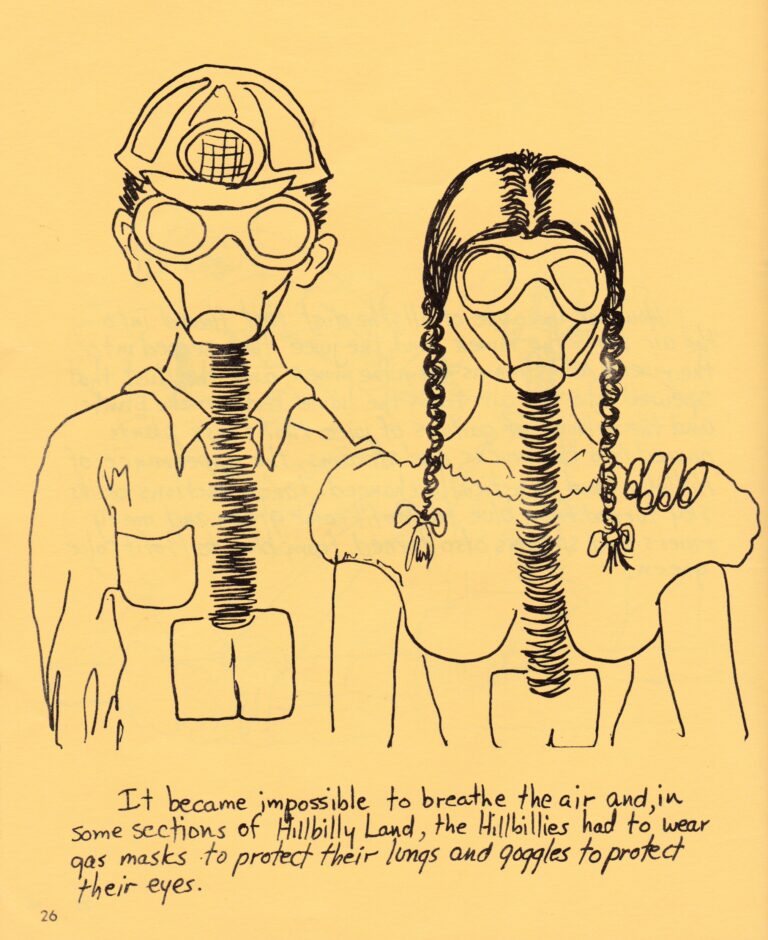

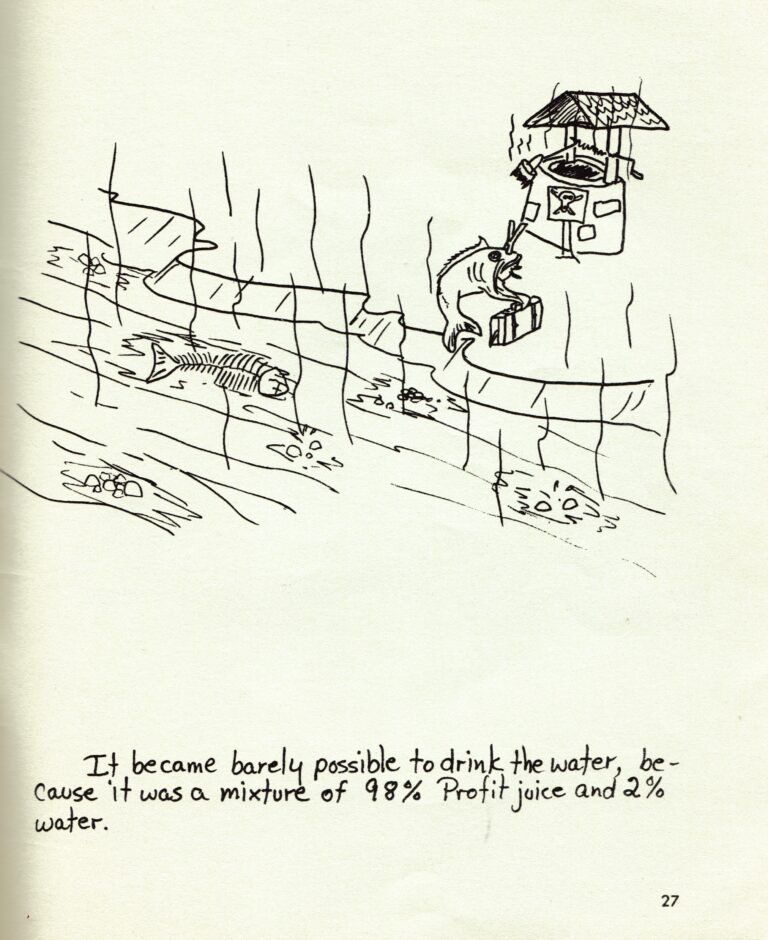

Eventually, the landscape is ruined, the air and water are thoroughly poisoned, and the Hillbillies realize that their homeplace is becoming unlivable. They organize to redress their grievances, and they angrily march to Capital City to speak with the Head Hillbilly – who is, notably, not a Royal Profiteer, but rather a wealthy elite in the pocket of the Profits industry who himself calls Hillbilly Land home but lives apart from his kin in a castle.8 He greets them warmly, listens to all of their troubles, and makes grandiose statements about how they’re all going to fix this mess. But the Head Hillbilly secretly casts a “Magic Word Spell” upon everyone who marched to his door. The Hillbillies leave in a daze of reassurances and platitudes. They later discover, when they recover their senses and become angry and turn back around to march on the capital again, that this spell will take effect and the cycle repeats itself. They can’t affect change, they can’t get the people in power to listen or make any sense when they do, they can’t make the destruction stop, they can’t win. “After several floundering trips in and out of the powerful force field created by the Magic Word Spell, the Hillbillies journeyed home in dismay and sank into dull despair,” the story concludes. “But after awhile, the Hillbillies decided that, after all, every kingdom and all people have their problems, and so they just ordered 1,500,000 gas masks and sets of goggles and left it to the next generation to try to solve the problems of Hillbilly Land.” The story begins with the archeological discovery of the ancient mountain kingdom of Hillbilly Land, but by the time the reader is holding the book, it has been destroyed beyond memory.

***

At the time The Hillbillys was published, Appalachian activists had already begun incorporating a framework for thinking about the region which drew global connections with “Third World” struggles for anti-colonial liberation brewing in the politics of urban-based organizations like the Young Lords and Black Panthers. As a response to endemic poverty and the increase of strip mining in Central Appalachia, many activists began to describe the coal-rich areas of eastern Kentucky and most of West Virginia as a resource-extraction colony inside the colonial borders of the United States: an internal colony.9

As a subjugated colony, the idea goes, the mountains of Appalachia have been taken over by wealthy industrialists from northern urban centers (steel magnates in Pittsburgh, for example), often with the collaboration of powerful regional elites. This colony has been deeply exploited for its resources – first for timber, then for coal – and the profits gained from this exploitation have left the region on the same trains that carted away the trees and coal. The people who call the region home, who were previously living in a quite different balance with the land before the colonizers arrived, experience systemic repression and poverty as their industrial colonizers “prevent autonomous development of the subordinate internal colony.”10 One can see the parallels with The Hillbillys: the whole region is Hillbilly Land, taken over by the Royal Profiteers, with the Hillbillies coerced into mining Profits under the jurisdiction of their Ex-Zecke-Tivs and the various localized Head Hillbillys.

When applied to Appalachia in AMP’s time, this colony framework proved particularly powerful for conceptualizing how it felt to live in the region: it codified existing folk understandings of the historical power of outside industry into a legible explanation for why things were the way they were. Thinking about and talking about Appalachia as an internal colony rooted in resource extraction helped activists describe to themselves and to the public what was happening to them as they experienced it, and in doing so connected their struggles to a broader internationalist, anti-imperialist project in the New Left politics of the era.11

Meanwhile, developing concomitant to these ideas was a burgeoning movement to reclaim “Appalachian” as an identity, articulating the regional culture as distinct, valuable, and legitimate. This very idea was an attack on the persistent negative stereotypes applied from outside the region, common tropes which explained Appalachia as a region “lost in time,” its unfortunate residents backward, stubborn, maybe even toothless. The hillbilly stereotype, in some form or another, is exhumed and given stage time for the curious outsider in a cycle that almost feels timeless. It is dizzying to try to clock the instances of paternalist national “interest” in the people of the region over the last few decades, even the last five years: articles about the “White Working Class” after the 2016 elections (and their tendency to “vote against their own interests”), J.D. Vance’s best-selling bootstraps memoir (and the backlash to it), countless articles about coal dependence vis-a-vis renewable energy, hot takes on the crisis of opiate addiction. Anyone in the US can summon a classist hillbilly stereotype and slot it into a mysterious landscape in a moment: these are perennial, perpetual, and seemingly bulletproof-true to most folks outside the region. To Appalachians, it is exhausting, demoralizing, oppressive.

In AMP’s time, Frantz Fanon had been writing about the psychology of colonized peoples in other parts of the world, and the Appalachian Left was paying attention and finding deep parallels on their home turf. Appalachians were not, in fact, the backward people they had been told they were. Instead, they were oppressed colonial subjects, and “the oppressed,” as Fanon noted, “will always believe the worst about themselves.” When this powerful effort at reclaiming and dignifying a regional identity entwined with the colonialism narrative, it explained what many activists and writers on the Left experienced as a broad, almost pathological fealty to the coal industry coupled with a pervasive lack of knowledge and pride in the original folkways of Appalachian people carried on from earlier generations: “Appalachian” was conceived as an oppressed minority identity.

***

As promoted by Appalachian Movement Press in the context of the Left politics of the 1970s, ideas about Appalachian identity were meant to draw predominantly from identification with the culture of place – namely, the mountains and valleys of the central Appalachian region. But in retrospect, the movement at a general level was expressing a primarily white identity through the absence of a diversity of voices in so many of the published materials and the language used therein. Reclaiming and defining an Appalachian identity drew lines almost exclusively around the Euro-ethnic settler traditions that had generationally assimilated into white culture by this time. Maybe because this reclamation work was building steam in the decade after the outmigration of a majority of the African American population to northern industrial centers in the 1950s and ’60s, it does not appear to have included Black Appalachians in practice. The exclusion of any Indigenous people who either preceded or continue to live in the region, or their relegation to history if mentioned at all, was a given.12 “Appalachian” is notreally meant to have anything to do with ethnicity, and proponents certainly did not directly claim “Appalachian” as a white identity. But it was not uncommon for activist writers to claim parallels to struggles against oppression by rural Appalachians and, in many cases, urban African Americans – and it’s these parallels that unintentionally defined the “Appalachian” identity of that period as separate from communities of color.13

We can critique this tendency while looking through a contemporary lens, but we can also, certainly, find much to learn from: as people watched Daniel Kaluuya in Judas and the Black Messiah portray Fred Hampton organizing with Chicago’s Young Patriots, who were white Appalachians-in-diaspora willing to work alongside Hampton’s Panthers and others for collective liberation, I hope we can begin to understand where this fight really was: the power of solidarity and cross-racial organizing, and why it was so dangerous to the status quo. Meanwhile, in my interviews, nobody I spoke with told me that their Appalachia in the 1970s was actually homogeneously white: Black Appalachian (or now, Affrilachian14) activists occupied critical leadership roles in organizing in West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky in that era and before.15 More recently, authors like Neema Avashia (Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place, WVU Press), William H. Turner (The Harlan Renaissance: Stories of Black Life in Appalachian Coal Towns, WVU Press), Crystal Good’s new Black-led newspaper Black By God: The West Virginian, anthologies like Y’all Means All (PM Press) and multi-faceted organizations like Black in Appalachia that combine filmmaking, podcasting, and rigorous archival work are all complicating the all-white Appalachia narrative. Many more voices are rising from the hollers and hills; yet it is the broad exclusion of people of color from the larger narrative of Appalachian history that has propped up some of the earliest and most damaging stereotypes that still haunt the region, and much of the literature about it, today. And it is this same amnesiac exclusion that can and is turned against Appalachians, with minimal editorial adjustments, by white supremacist organizations who often focus their efforts on rural communities in poverty looking for answers.

***

Earnestly promoting Appalachia-as-colony would be considered gauche in most academic circles today. The conception does begin to fall apart the more you begin to pick at the label. For starters, there’s the reality of the settler colonialism that formed the areas we now refer to as West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio. As in so many pre-coal “colonial” narratives, the landscape that serves as the backdrop for The Hillbillys portrays an “Idyllic Holler” as the beginning of time itself.16 Harless’ “ancient mountain kingdom called Hillbilly Land” is a familiar locale which is replicated, often and under many names, in legends wherein white settlers have existed since approximately the beginning of time, irrespective of the vast Indigenous societies which thrived more widely in the region before settlers began to encroach.

These stories meld too easily into prevailing mythos about a hardy Scots-Irish people having found themselves in a kind of mountainous tabula rasa just a couple of generations before the coal barons arrived. This genesis idea is remarkably persistent and bolstered by the oft-taken-for-granted fallacy that the area was “only a hunting ground”17) for Indigenous peoples and so, since the land never really “belonged” to anyone, nothing was actually taken. It’s a fantastical omission that assumes a kind of white Appalachian indigeneity and creates a false absolution which chews at the table legs of the internal colony idea and, more broadly, undermines the kind of deeper reckoning with settler-colonial history that is really needed.

Talking about Appalachia as a colonized region will also put you on the wrong side of understanding the mechanics of capitalism, although here the distinctions begin to get blurrier. David Walls writes that activists like the AMP founders “hit upon the internal colonialism model for reasons that had more to do with the focus of the New Left in the late 1960s – imperialism abroad and oppression of racial minorities at home – than the appropriateness of the model to the Appalachian situation.”18 Walls and others suggest that regional plight should in reality be seen as part of the typical functioning of any industrialized capitalist state, where peripheral areas are sacrificed to bring resources to core centers – southern West Virginian coalfields, for example, sacrificed to keep the lights on in Philadelphia. It’s not a colony, exactly, but it is a “sacrifice zone.”

Maybe that distinction catches traction in journals not widely read outside of academic circles. Meanwhile, the colony model still appeals on the ground as an organizing concept today. All of the baggage is still intact, and yet it is a useful shorthand which helps to crystallize how it feels to live in the rural parts of the region for many people today.19 I struggled for a long time when writing the book with how to reconcile the refutations I found in academic journals and my own concerns with the articulated experiences of the people I knew who grew up in the coalfields. There, quite often, the resource colony idea (if it comes up) is spoken of as fundamentally true. And why not? Looking at the single-industry domination of areas of southern West Virginia over the last century, for example, there sure is a hell of a lot of what looks like “prevent(ing) autonomous development of the subordinate internal colony” going on – just ask folks in what their options are for earning a wage. The vocabulary won’t often match the one I am using here, but it should not be a surprise that the idea retains a persistent hold in some form or another – even if the concept could use a retooling along more contemporary decolonial lines.20

That retooling could start with a reckoning with the history of the land. To begin that reckoning, we could look at what ecologists call the “shifting baseline,” a concept that The Hillbillys illustrates well. The term describes our tendency to measure change in an already wounded landscape based only on how much the ecosystem may have deteriorated within our lifetimes. We then use this metric to figure out how much work we need to do to “fix” things, so that cleaning up a local creek, for example, often means bringing the ecological balance of it back to how it looked when you fished or swam in it as a child. Your own autobiographical experience is usually your baseline, and that reference point shifts forward for each generation. This impulse is reflexive, and it fails at acknowledging a more complex, longer history of the land. The health of that local stream would have been fantastically different, and more robust, hundreds of years before you were born, and it’s that baseline we should be aiming for. We often do this when it comes to understanding other histories of land as well: The Hillbillys in Hillbilly Land had a baseline of their own existence that mirrored that of many Appalachian history narratives: history for them starts right before the coal barons showed up. The “idyllic holler” is a part of this, a persistent narrative anchor which keeps us blind to the larger complexities of the history of the land and the people that call it home. Taking these blinders off is a powerful first step.

Packaging The Hillbillys as a “children’s book” helps bring a little levity to its overall bleak tone. The whole package is rare to see in movement publications of this kind, at least from AMP – the press specialized in buoying regional identity and determination, not harping on the despairing side of things. The Hillbillys was probably never read aloud during storytime in regional daycare centers, though I suppose one can hope. Besides putting narration to the frustrations of the Left in their time, Harless and Cutler set up a backdrop to the guiding mission behind Appalachian Movement Press: emancipation of Appalachian people led astray by the brutality and false promises of a “colonizing” coal industry. Whether or not the intellectual frame holds all of its water under scrutiny, it has a staying power.

Over the decade between 1969-79, Appalachian Movement Press became a vital connective thread during a critical time in the struggle for human rights and environmental justice in the region, developing an independent regional press with the overall mission of uplifting Appalachian people to self–determination. The printshop is a little-known piece of the history of the Appalachian Left, and importantly the Appalachian Left itself is a little-known piece of US movement culture of the 1960s and 1970s. Written during a remarkable decade of struggle in central Appalachia, The Hillbillys doesn’t offer a happy ending. The authors left that up to future generations. “Going through those (AMP) publications and reading them,” writer Jim Branscome told me during a phone interview at the beginning of 2019, “you would think that the mountains were on the edge of a revolution.”21

Big, deep gratitude to Jessica Scott and Ben Case for early critical readings of this essay which helped to put it on the right track.

The Hillbillys was published in only one, undated edition by Appalachian Movement Press, between 1970-72. This presentation in Viewpoint is the first time in over forty years that this publication has been made available to the public outside of a small number of library collections. The book So Much To Be Angry About: Appalachian Movement Press and Radical DIY Publishing, 1969-1979, profiles the history of AMP and the people who operated the printshop, and dives into many more of the publications that rolled off their presses, including several reproductions of whole publications. The book is available from West Virginia University Press.

References

| ↑1 | AMP co-founder, Tom Woodruff describing the initial vision of the organization, from the foreword to A Time For Anger, by Don West. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The central Appalachian region, where Appalachian Movement Press was focused, encompasses eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, eastern Kentucky, parts of western Virginia and eastern Ohio, and the entire state of West Virginia. From Appalachian Regional Commission, “The Appalachian Region.” |

| ↑3 | Josh MacPhee, “A Brief History of the Movement Printshop.” introduction to Shaun Slifer, So Much To Be Angry About (Morgantown: WVU Press, 2021). |

| ↑4 | Black lung, or coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, is still a prevalent workplace disease caused by inhalation of coal dust. Many of my friends who worked in mines for years cannot claim benefits for their black lung disease through a complicated morase of regulations that keep compensation limited. Editor’s Note: See the updated version of Barbara Ellen Smith, Digging Our Own Graves: Coal Miners and the Struggle over Black Lung Disease (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020); and Chris Hamby, Soul Full of Coal Dust: A Fight for Breath and Justice in Appalachia (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2020. |

| ↑5 | Mountain Call, out of Mingo County, WV was one such magazine, which straddled a quasi-psychedelic drop-out ethos and a class-conscious, pro-union community and regional pride. MAW: Magazine of Appalachian Women, was another key publication from AMP’s last years, the first (known) feminist magazine in the region, which thrived for four ground-breaking issues before AMP itself began to implode. |

| ↑6 | See Mother Jones’s quote; “Sit down and read. Educate yourself for the coming conflicts.” |

| ↑7 | Find a Grave, “Roderick Mansfield ‘Rod’ Harless”; see too the obituary published in the Charleston Gazette-Mail. |

| ↑8 | AMP readers would have been familiar with local and regional corruption that mirrored this, whereby familiar local elites acted in the interest of, and from the pockets of, absentee corporations. |

| ↑9 | Editor’s Note: Another key focus of the internal colony framework, hinted at in The Hillbillys, was the role played by regional development commissions like the Appalachia Regional Commission – as power brokers and key components of the state apparatus. See David Whisnant, Modernizing the Mountaineer: People, Power and Planning in Appalachia (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979). |

| ↑10 | David Walls, “Internal Colony or Internal Periphery?,” in Helen Lewis, Linda Johnson, and Donald Askins (eds.), Colonialism in Modern America, The Appalachian Case (Chapel Hill, UNC Press, 1978): 319-49. Editor’s Note: See too another well-known presentation of the Appalachia as internal colony thesis: Keith Dix, “Appalachia: Third World Pillage,” Antipode 5, no. 1 (March 1973), 25-30, which summarizes some of the work Dix was doing with the People’s Appalachia Research Collective and the group’s journal, People’s Appalachia. |

| ↑11 | Walls, “Internal Colony or Internal Periphery?.” |

| ↑12 | Editor’s Note: But see the brief discussion in the Communist League’s (later Communist Labor Party) report on Appalachia from the early 1970s on Appalachia. |

| ↑13 | In other words, as Yvonne Farley told me during an interview in 2019, “Nobody was really calling Black people hillbillies.” |

| ↑14 | “Affrilachian” as a term for African Americans who identify as Appalachian is attributed to the Kentucky-born Black poet and scholar Frank X. Walker |

| ↑15 | Miners for Democracy, as just one example, had many powerful Black leaders, reflecting the history of the United Mine Workers as one of the earliest racially integrated unions stretching back to the Mine Wars era (1900-1921). |

| ↑16 | Allen Batteau coined the term “Holy Appalachia” to describe this mythology of an untouched population of white settlers in Appalachia, which he extended to include the abolitionist history of the region and the persistent idea that the mountains were always a bastion of antiracist culture. The term “Idyllic Holler” is my own, a specific locale within Holy Appalachia that is replicated indefinitely through story. The Appalachian colloquial “holler” comes from “hollow,” the valley area between mountains, often running along a creek or other watershed. |

| ↑17 | The usually accepted, generally taught modern history of West Virginia continues to claim that the area was merely a “hunting ground” and that there were no Indigenous Peoples fully established in the area when the white settlers came. However, as historian Bonnie Brown suggests, even if an area were considered territorial hunting ground before settlers came, this could still mean that Native people were occupying the area for half of any year. Corey Knollinger, “Wild, Wondering West Virginia: Exploring West Virginia’s Native American History,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting, February 7, 2019. |

| ↑18 | Walls, “Internal Colony or Internal Periphery?,” 322. |

| ↑19 | If you are intimate with the complexities of addiction, then it is not hard to see something familiar in the desperation in The Hillbillys, the stage being set for the trauma that can happen in any community fighting destruction brought upon it by outside forces. |

| ↑20 | Editor’s Note: Comparisons could be drawn with new understandings of “extractivism” that have emerged from contemporary struggles in Latin America: see Verónica Gago, “Financialization of Popular Life and the Extractive Operations of Capital: A Perspective from Argentina,” South Atlantic Quarterly 114, no. 1 (January 2015): 11–28, and Verónica Gago and Sandro Mezzadra, “A Critique of the Extractive Operations of Capital: Toward an Expanded Concept of Extractivism,” Rethinking Marxism 29, no. 4 (2017): 574-591. |

| ↑21 | James Branscome, interview by author via telephone, February 12, 2019. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine