Introduction

The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) was one of the most dynamic black radical groups to emerge in the 1960s and 1970s. Founded in Cleveland, Ohio in the spring of 1962 by students at Case Western Reserve University and Central State College at Wilberforce, RAM included the young radicals Max Stanford, Donald Freeman, and Wanda Marshall at its core and maintained a close association with nearly all the major radical figures of black nationalism. James Boggs, for example, served as the group’s Ideological Chairman, Robert F. Williams as International Chairman, and Malcolm X as International Spokesman. In fact, RAM emerged early on as a kind of organizational node for the constellation of new black radical groups appearing in the 1960s – members of SNCC and the future Black Panther Party, for example, were directly influenced through encounters with Stanford and fellow RAM cadre Ernie Allen, respectively. The group not only kept radicals tightly connected, but it also played a crucial role in the circulation and dissemination of revolutionary black nationalist theory through its journals Black America and RAM Speaks, and thanks to the appearance of excerpts from Stanford’s “Towards A Revolutionary Action Manifesto” in the May 1964 issue of Monthly Review.

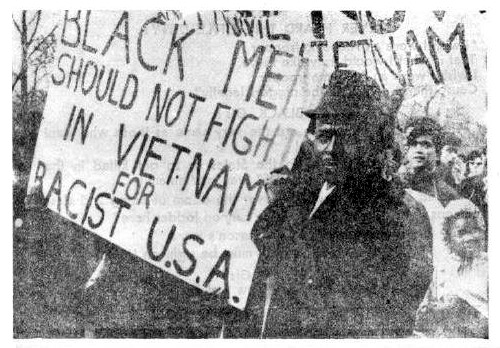

According to its principal theorist, RAM’s central tenet was “that the Black liberation movement in the United States was part of the vanguard of the world socialist revolution.” Throughout its existence, RAM looked to struggles abroad for strategic insight, continually refining this deep connection between international revolutionary currents and the national struggle of black people at home against what RAM labeled internal colonialism. Indeed, this identification as a colonized people allowed African Americans to advance a very unique vision of solidarity with struggles abroad. RAM could oppose the war in Vietnam, for example, not only on the grounds that African Americans were disproportionately drafted, that they faced racial discrimination at the front, or even that the money wasted in Vietnam could be better spent assisting poor black communities. For black revolutionaries, the basis of their solidarity with the Vietnamese lay in the fact that they experienced a similar form of colonial oppression. As colonial subjects within the borders of the United States, African Americans did not owe any allegiance to the oppressing government – granting an effective basis for RAM’s advocacy of armed self-defense and detailed considerations on urban guerilla war.

RAM’s open letter to “Our Militant Vietnamese Brothers,” included in the Fall 1964 issue of Black America and presented below, implies that African Americans and Vietnamese not only lived in related colonial situations, but fought against same common enemy, American imperialism. What’s more, they struggled for the same goal: national liberation. In November 1965, Robert F. Williams even traveled to Hanoi to speak at the International Conference for Solidarity with the People of Vietnam as RAM’s representative, solidifying this alliance. There, Williams compared the escalating and aggressive actions of the United States in Vietnam to the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, a mobilizing catalyst for some of the most intense campaigns of the Civil Rights movement in the South. In turn, the head of the NLF in South Vietnam, Tranh Van Tran, gave a speech in support of struggles against racism in the United States and South Africa, echoing Mao Zedong’s address on the same topic two years earlier. These real international linkages updated a prominent thread in black anticolonial thought and activism: Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, Vicki Garvin, and Claudia Jones all made the bridging of these national and international dimensions a focal point of their political work.

The decision to declare their solidarity with the United States’ military enemy on July 4 is significant, then, because it allowed RAM to point to the utter hypocrisy of America’s myths about being the land of the free and independent. At the very same time that the United States celebrated its independence from a colonial power, it waged a war to crush the independence struggle of another people – independence, it seems, was not for everyone. Of course, like forms of international solidarity, this strategic and critical reference to the signing of the Declaration of Independence has a much longer history. On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass famously asked, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” The Declaration, he argued, did not apply to all Americans:

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. — The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine.

Later, after 1945, when the United States began to fashion itself as a kind of global liberator, other oppressed peoples would strategically redirect America’s ideals for their own ends. In fact, the very first line of the 1945 Vietnamese Declaration of Independence explicitly quotes the American version. If everyone is allegedly born free, and national liberation is a right, the Declaration argues, then why does this not apply to the colonized peoples of the world? For RAM, this kind of thinking and enunciative power applied to Black Americans as well, and the two struggles for full self-determination, the ones at home and those abroad, were treated as inseparable.

– Patrick King and Salar Mohandesi

Greetings to Our Militant Vietnamese Brothers

July 4, 1964

On this Fourth of July 1964 when White America celebrates its Declaration of Independence from foreign domination one hundred and eighty-eight years ago, we of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) congratulate the Vietnamese Front of National Liberation for their inspiring victories against U.S. imperialism in South Vietnam and thereby declare Our Independence from the policies of the U.S. government abroad and at home.

RAM does this because, as the Black Liberation Front of the U.S.A., our philosophy is one of world revolution of oppressed people rising up against their former slavemasters. Our movement is a movement of black people who are coordinating their efforts to create a new world free from exploitation and oppression of man by man.

We of RAM know that in South Vietnam today, U.S. imperialism is trying to fill the vacuum left by the Indochinese rout of French imperialism ten years ago, as elsewhere in the world it is trying to fill the vacuum left by Britain, Holland, and the other European imperialist powers. We are well aware of the undeclared war that the forces of U.S. imperialism are fighting today, against the people of Southeast Asia, in the name of the “Free World,” and also of the intrigues by which U.S. imperialism seeks to divide your country; in order to cripple its economy and make it completely dependent upon U.S. aid. We know that U.S. capitalism is the citadel of world capitalism. That is why we of RAM do not seek assimilation or integration into this “Free World.” We do not want to share in the oppression of our brothers anywhere on earth; we will not join in the White American counter-revolution that is attempting – at home and abroad – to crush the mounting revolutionary struggles.

We hope that our solidarity will encourage our brothers in South Vietnam and the world over to intensify their revolutionary efforts so that in the near future, all of us will be able to meet and lay the basis for a new world society in which all forms of colonialism and exploitation – political, economic, social, and cultural – will have been buried and all those who have been oppressed will have the power to decide their own destiny. Then and only then will men be able to live as human beings and not as slaves and slavemasters.

This article first appeared in Black America, Fall 1964, page 21.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine