Patrick King: We want to start from a methodological standpoint, thinking about what kind of intervention Black Against Empire makes in terms of social movement theory, a field which can often seem divorced from a real understanding of political practice. There are two concepts that you and Waldo Martin deploy in your book that we’d like to discuss: one is what you call a “methodology of strategic traces” or a “strategic genealogy”; and the other is the focus given to the “insurgent practices” of different movements, organizations, and groups – in this case, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. What was your aim in using these two concepts to serve as guiding threads for the book and your sociological work in general, and how do they help us move beyond the often narrow frames of social movement theory?

Joshua Bloom: The big theoretical problem that was front and center going into the book was thinking about why and how people build power from below in some movements, and asking why is that so rare. The social movement literature and social movement theory provides a number of tools to think about those questions, but I was pretty dissatisfied with most of those tools. I felt like they erred on two sides of the structure/agency debate, a problem that the literature has tangled with for awhile, and I think there’s a broad consensus that pretty much none of the solutions are satisfactory.

Around 30 years ago, there was a shift within social movement theory from social-psychological, collective behavior, and cognitive dissonance-based theories that look at movements as irrational, to the frameworks that were developed in studying the civil rights movement, especially political process theory and, relatedly, resource mobilization theory. I think that the way that political process theory in particular tried to solve these problems is by agglomerating several different variables, stacking them on top of each other as if they were all these independent determinants, in this very social-scientific way. I do think it moved the discussion forward, and it provided some really important ways of thinking about some of the important processes going on, but I think it missed the key way in which what people do matters in a political context. On the one side, here was this understanding of a political opportunity as the destabilization of social roles in a given moment, thereby advantaging a group and really fomenting insurgency or movement by that group as if what people were doing wasn’t determinant or determining how those structures mattered. Then on the other side, there were these very ideational and agential types of processes, that in many ways were stripped of context – like framing, which is sometimes used as if people could sort of just all get together have this discussion, where they come on the same page, and then you’re going to get a movement growing out of that, as if there’s no real relationship to what’s going on structurally.

I came into this project dissatisfied with that duality, and having worked as an organizer and as an activist for many years, I wanted to center the question of what people are actually doing and why that works in a given moment, and how that is what generates movements. That’s the basic focus.

The methodological idea of strategic genealogy, which came out of earlier discussions around the book, was intended to get specifically at that relationship in relatively informal way. I mean this was written for a broad popular audience; there’s a strong theoretical dimension that drives and guides the analysis, but it’s really a history – an effort to tangle with all the available evidence and given events, to be able to then try and make sense of the development of those events. This isn’t a heavy, quantitative analysis – in some of my later work, I’ve moved on to try and do some more systematic and rigorous testing of some of the ideas that grow out of this history and this study, but the idea of strategic genealogy was really to look at: what are people doing, what are they saying, and how does that change from moment to moment over the course of the movement’s development, and where and why do particular new forms of strategy get adopted? And then, what are the consequences of those changes. You’re looking at two things at once, in parallel: first, the trajectory of the movement – how many people are participating? what kinds of attention is it getting? what level of influence is it garnering? Second, you’re looking at what exactly people in the movement are doing, conjuncture by conjuncture. So the idea is that by looking at those two questions in a parallel fashion, you would get a sense of what that relationship was. Why was it that at certain moments, the things that people did differently brought new kinds of following and support?

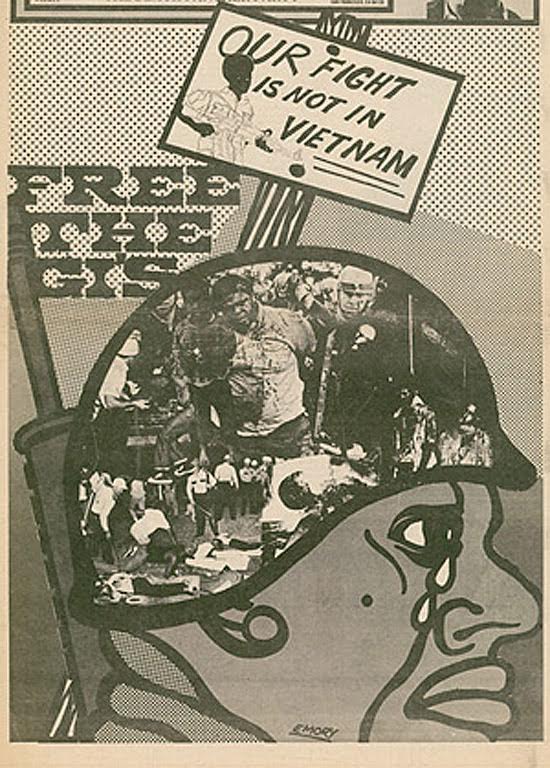

To use an early example, look at what the Black Panther Party did in the first six months with the tactic of policing the police and the armed patrols. Every piece of what they did was drawn from something else: the name and symbol of the Black Panther from the Lowndes County Freedom Organization; the idea of armed self-defense from Robert Williams, the Deacons of Defense to some extent, and again, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization; the kinds of claims about their relationship to the black community were drawn from Malcolm X; and a lot of the anti-imperialism was taken from their work with the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) and their front groups. And finally, there was the piece of community armed patrol, which was them saying, “we’re going to follow the police around.” So, a lot, if not all, of the pieces were already there, but independently none of those parts worked. What Huey Newton and Bobby Seale did was they figured how to put them together in a way that they could actually stand up to the police, and in that way, attract and draw support from what they called the “brothers on the block.” And that really worked. It first propelled them into building a small leadership. Then, when Denzil Dowell was killed in Richmond, that set of practices, combined with their standing up legally to police but with arms, had hundreds of black people, of all stripes and ages and with their own guns, coming out to the corner following this killing by police without any accountability. From those claims and set of practices, and then the newsletter that grew into the Black Panther newspaper, they were able to get all kinds of support and placed them onto a broader stage. And very quickly, in response, the state of California tried to change the law and change the context in which they were able to do that.

It’s easy to see, then, how through that informal method of strategic genealogy, the relationship between what the Panthers are doing and why it works in a given moment is made intelligible.

PK: And this is much more dynamic than seeing these practices, what you call insurgent practices, as a repertoire or inventory that can just be taken up and used – even if we account for modularity – but actually involves real inventive strategies for combining and translating these practices into different contexts.

JB: Yes, absolutely. The scholar that’s done the best with thinking about these kinds of repertoires is probably Charles Tilly, but even then, he looks at these questions from 30,000 feet off the ground. There, the idea is that within a certain regime – a given space and a given time – there’s basically a fairly set repertoire of tactics, essentially. People can modularly draw from these available tactics, and there’s some kind of slow evolution over time. But there’s no account of how these practices actually generate movements, and that’s where I think the crux of the issue is. I don’t think that people individually make movements; if you look at the great leaders and you take them out of the movement context, oftentimes their capacity to actually build a movement falls. Conversely, if you look not only at the Black Panther Party, but the civil rights movement, or the earlier instances of black anti-colonialism that I’ve looked at – but think also about the industrial unionism of the 1930s, or even internationally, the Intifada – if you look pretty much at any movement, there is usually an arc of mobilization and demobilization centered around a particular form of practice. This involves certain types of transitive claims – we can overcome this form of oppression by challenging these authorities in these ways, and here’s how we’re going to talk about it and here’s the specific things we’re going to do. But if you look at the black freedom struggle closely, the mobilization doesn’t follow a singular kind of arc of mobilization-demobilization. For the black freedom struggle as a whole, in fact, it disaggregates into these series of smaller movements which have a lot of coherence both in terms of the kinds of things people were saying, the kinds of targets they were challenging, and the kinds of tactics that they were employing, who was trying to repress them, and who was coming out to support them. Those movement dynamics are very coherent and consistent across those arcs of mobilization and demobilization, and they center very much around practices, and how practices become a novel source of power.

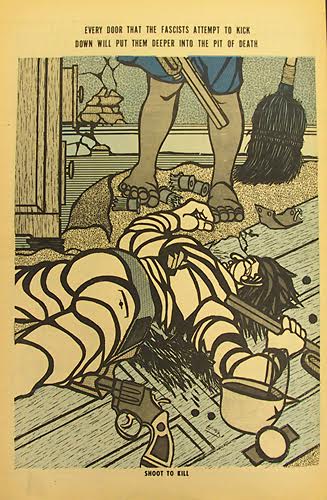

This idea of what I’m now calling insurgent practice theory emerged from Black Against Empire. It’s not something I went into this project with; it’s part of a bigger piece of what came out of looking very seriously into these relationships within the history of the Black Panther Party. What the Black Panther Party activists and organizers achieved was a sort of cultural technology, which provided a source of power when they found and developed a set of insurgent practices that was able to do two things. One was to disrupt business as usual – to make customary social relations and institutionalized power impossible to conduct as usual. With the BPP, you see that mostly in terms of containment policing practices. It’s one thing to talk a lot of rhetoric like RAM was, before the Party ever got off the ground; it’s another to create the conditions under which there can actually be armed confrontations with the police in cities all across the country. Those kinds of confrontations make customary containment policing very difficult. The challenge, however, is that disruption is always available, it’s always possible to violate social institutions. The problem is that repression is usually very effective. So when people violate established social institutions and challenge established authorities, they’re readily repressed most of the time. What the BPP was able to do– and they were very much trying to emulate the civil rights movement in this regard, and they succeeded to a certain extent – was to create a cultural technology that was able to sustain disruption, and sustain disruption as a source of power. They were able to do this because the character of the practices that they had developed, that cultural technology of armed self-defense coupled with this anti-imperialism, in that moment, the more authorities repressed them, the more they were able to gather broad allies, who otherwise wouldn’t have supported the party in the first place but also had their own reasons to really feel threatened by the status quo. This was an effective and difficult cultural technology: the more you repressed it, the more you drew allied support and fostered broader mobilizations. So in a nutshell, that’s the theory of insurgent practice that grew out of the study.

Ben Mabie: Your book is also one of the first to really probe the strategic dilemma faced by the Panthers in regards to organizational form: it was caught between being a formation that had origins in a very specific context (the migration patterns of African Americans from the South to the West Coast, the subsequent industrial downturn and campus struggles in Oakland) and a very rapid explosion into a nationwide social movement. After the departure of Eldridge Cleaver’s faction in 1971 and Newton’s regroupment of the BPP to Oakland, the extreme poles of a guerilla war scenario or a social-democratic electoral strategy (with the Bobby Seale mayoral and Elaine Brown city council campaigns) seemed to become the only options. How do we make sense of this split? Did it concern the changing nature of the Party’s base – a need to drastically shift from their initial focus on the lumpen class or “brothers on the block”? How can this dilemma, which seemed to affect many groups at the time, help us with our current strategic questions, especially in light of the inventiveness of some organizational aspects of the Panthers?

JB: There’s a lot in there, so let me start off by saying what I don’t think answers that question. A lot is often made about this idea that the Black Panther Party’s base was the lumpenproletariat, and the lumpen, as Karl Marx said, is impossible to organize. You need the discipline of the industrial working class and this that or the other. But you know, those characteristics of the lumpenproletariat were both a strength and weakness of the Party from its inception through way past its demise. Moreover, the Party was never monolithically comprised of the lumpenproletariat: it always had college students, it always had working class members, and there was some lumpen. Part of its strength and power, of course, was its ability to organize the “brothers on the block,” which is another way of saying the lumpenproletariat. The weaknesses – the difficulty of discipline – and the strengths – the capacity for resistance – were always central to what the Party was. I don’t think they drove the split in any significant way. I don’t think you had a different composition in terms of class basis or class constituency of the two sides of the divide. Nor do I think that in some abstract sense either of those sides spoke to the core interests of the lumpen, one versus the other or anything like that.

I think that really the cause of the split goes back to the fate of the insurgent practices the Party built, and was able to use to build power and mobilize people. In many ways, the story is very parallel to what happened with the civil rights movement. I’m just finishing up a quantitative analysis, and if you look at the arc and trajectory of nonviolent mobilizations, specifically civil rights mobilizations in the postwar decades, there’s a pattern that happens within nonviolent mobilization that precedes the turn towards violence. The first thing that’s interesting is that all those anecdotal generalizations about a move towards violent mobilizations in the late 1960s absolutely hold quantitatively. When you do a coding of events on a large scale, there’s a very striking shift within black mobilization towards much more violent mobilization, really post-1966, 1967. It gets much stronger into 1968, ‘69. You obviously have some important earlier forms of violent mobilization as well, but there’s a very striking shift in quantity and character from nonviolence to violence.

If you unpack what happens within the nonviolent mobilization, what insurgent practice theory predicts absolutely holds, which is that there’s a tight coupling of repression with nonviolent mobilization through the late 1950s into the early 60s. The level of mobilization escalates quickly, coupled with very high levels of repression of nonviolent civil rights mobilization and protesters – you think about the arrests, the beatings, the white violent mobs, the killings. When you look at those rates, those rates are very high and they’re tightly coupled, through the late 50s into the early 60s, with the level of nonviolent mobilization, and all that escalates together. What happens after the passing of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act is that with desegregation, the targets that the civil rights movement aimed for are no longer available. Civil rights mobilization was a cultural technology – a movement technology, a political technology – oriented towards disrupting and dismantling Jim Crow. And it worked, because it disrupted Jim Crow directly: it bodily violated it in such a way that drew and exposed the brutal repression of segregation, so all kinds of external actors, not least the federal government, legally, politically, and militarily intervened to crush and dismantle the Jim Crow system. I mean, concerning the federal government, President Kennedy’s constituency was such that he was not going to get up and be a champion of the civil rights movement and dismantling Jim Crow – they were forced to do that, and they were slow about it. But those changes happened because the civil rights movement developed a set of insurgent practices which forced them to intervene, due to the way that it exposed that brutality through the repression of civil rights practices and movement actors.

Once you desegregate and dismantle the system of segregation in the South, what targets can you use these civil rights practices against? Without Jim Crow, how do you have a civil rights insurgency? You don’t. So if you look at the same organizations – look at the history of CORE in the North, during the early 60s, the heyday of the civil rights movement. Same organization, same leadership, tons of resources, same claims, trying to do the same kind of thing, but it’s about maybe getting jobs in segregated Woolworth’s, and you have year-long campaigns, people are beaten, and what do you get? You get one job, a token job, because it’s been desegregated. There’s no firm line. Civil rights insurgency never works to dismantle economic exclusion or political exclusion. It never works to dismantle ghettoization. It works for one thing, which is to dismantle Jim Crow. So what you get in the civil rights movement is a very similar trajectory: that set of practices follows a course where it becomes a powerful source of power through sustained disruption, by sustaining disruption, to a certain point, until the context shifts enough that it can no longer serve as a source of power in that way. In the civil rights movement it shifts because the targets for insurgency are removed very directly.

In the BPP’s experience, the relationship is less direct. The Party is at the center of a much broader insurgency – the Panthers are by no means the only set of insurgents during the period; there are all types of insurgencies that are working together, and the BPP is an important part of that mix. There’s all kinds of anti-imperialist insurgency, domestically and to some extent coupled with and working with these international insurgencies. You also have reshuffling within the Democratic party itself. When LBJ and the Democrats created federal affirmative action legislation, it wasn’t just in response to the civil rights movement, and the same goes for the integration of the Democratic Party machines in the cities – where you get black people actually running for office and winning in these cities with large black populations in the North. That’s in the late 1960s and into the 70s, and it happens in large response to the turmoil within the party. The Democrats don’t roll back the draft, and in fact in ‘68, it’s not just what’s going on the street during the Democratic Convention, but what happens inside: 80% of Democratic voters vote to end the war and the party says screw you, we’re sticking to our pro-war platform and candidate. It’s only when there continues to be this massive social destabilization – think about May 1970, with basically all the good schools being shut down, and most of the rest of them – that a series of concessions to the middle are made. Those concessions make it impossible to sustain the kind of practices – anti-imperialist claims, coupled with armed self-defense, as well as efforts at local self-governance – that the Black Panther Party is championing. We make this claim explicitly in the book: if there still were only six black representatives in Congress and no significant black local leadership electorally, and no access for black students to education at elite institutions or at least very little, and a massive draft, and all these anti-imperialist struggles going on globally, you would still have a BPP today.

Why does the BPP end and why does it split? It splits and ends because it becomes increasingly difficult to sustain those practices as a source of power and more and more allies obtain institutionalized ways of meeting their needs. Who is it that mobilizes for national response to the killing of Fred Hampton? It’s Whitney Young, the head of the Urban Defense League! You cannot get more moderate than the Urban Defense League. And why? Because he supports the Panthers? Of course not. It’s because you can’t go and kill young black activists in their beds, and we can’t get our kids from respectable black families into middle class or good universities, or make legitimate runs for electoral office. And who is it that is doing the law cases, buying the newspapers, and so on? A lot of that is the friends and families and the draftees. As those dynamics change, it becomes harder and harder to support. At the same time, the Party has become really big and influential, and so it’s very much in the spotlight and those pressures are getting more intense as well. The internal contradictions are there all along, but they’re containable so long as the set of insurgent practices provides a way to build power from below.

BM: I just want to clarify. Are you saying that the insurgent practices themselves produce power insofar as they enable the strategic alliances you’ve just discussed? Is that the crux of the kind of power that you’re describing them as producing? Because it seems that what makes the insurgent practices work, despite the repression, is not only their disruption, but the the way in which disruption and repression expanded the Party’s capacity to articulate unity between all these different struggles that were taking place concurrently: so, to maintain a program of self-defense while also to speaking for the black middle class, students resisting the war, etc. They are able to put forward, if not a program, then at least a vision of common struggle. So that moment of decomposition, breaking apart, disarticulation, is I think what we’re trying to get at in the question about the relationship between these insurgent practices and the BPP’s base. Maybe it would be clearer to talk about that moment in terms of these strategic alliances.

JB: Almost, I would put it a little differently. I think the crux of the power is the disruption which, again, is something that is available very widely. I could go right now and lay down in the middle of the street, and there’s disruption right there. If you look at the civil rights movement, there was never a dissolution of alliances. The federal government never renounced civil rights, liberals never advocated going back to having Jim Crow, black churches never apologized, etc. So with the civil rights movement, those alliances were never degraded. The crux of the issue, the source of power, is the form of disruption. In the civil rights movement, the source of power was being able to interfere bodily with Jim Crow. For the Panthers, it was being able to interfere directly with containment policing. For the civil rights movement that leverage, that crux of power, was removed because concessions were made directly to the movement. For the BPP, those forms of disruption are available today: you could still stand up to police and have some sort of armed movement. Now, you’d get killed and labelled a terrorist, and everyone would be happy that you went to prison. So that’s the second piece. What makes that crux or leverage sustainable is that it drives a wedge in a broader institutionalized cleavage. It’s not that Whitney Young ever agreed with the BPP, it’s that there was a big political cleavage between all black political organizations, including the most moderate, and all the establishment institutions, whether you look at electoral representation, or municipal hiring of police, or access to education, class mobility, etc. So there’s this massive, much larger, political cleavage that’s way beyond what the Party is, or who the Panthers’ constituency is, for that matter, it’s this very broad institutionalized cleavage. What the Party’s practices did is they created disruption in a way that drove a wedge into that cleavage, that brought support from the other side of that cleavage. Not because those people on the other side supported the Party, but because the repression of the Party was threatening to them.

BM: Your book firmly reorients the history of the Black Panther Party towards its anti-imperialism, as we’ve briefly discussed – after all, you titled the book Black Against Empire, and the first scene of the book describes Huey Newton’s meeting with Zhou Enlai in Beijing. The Black Panther Party, along with many other Black Power currents, argued that because African Americans constituted an oppressed colony inside the United States, their struggle for self-determination was indissociably linked to the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist revolutions rocking the globe from the 1950s to the 1970s. The Panthers had very close ties to revolutionary regimes, such as Algeria, and supported anti-imperialist struggles, as in Vietnam and Palestine. But these other anti-imperialist struggles in turn supported the Panthers, supplying them with ideas, inspirational examples, and aid. Thus, you argue that anti-imperialism was not a mere supplement to the Party, but a fundamental axis of their politics. What, exactly, did the Panthers mean by imperialism? Would you say that the broader anti-imperialist context of the time was a primary condition for the success of the Black Panther Party? Where do we stand now that imperialism has changed, and the backdrop of Third World revolution that helped make the revolutionary movements in the advanced capitalist world possible in the 1960s and 1970s no longer exist in the same way?

JB: So there’s actually three questions in there, and I’m going to take the second one first. Was global anti-imperialism central to the particular form of practice that was advanced by the BPP and its power? Absolutely. The particular form of insurgent practice that the BPP developed, and that created this kind of sustained disruption, for really only three years, depended in a tremendous way on the extent and existence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally. Not only directly for funding and political support and these kinds of things, which in reality was not that significant – it’s not like there was that much money coming in or anything like that. Yes, Cuba said they were going to build a military training ground, but it never happened, and yes, there was an embassy in Algeria, but how many Panthers were there? You can count them on a hand or two. So was that essential for the resources of the movement? No. Was it essential for the political imaginary and the way that the Party allied with other constituencies in the United States? Absolutely. You couldn’t have had an anti-imperialist anti-war movement with those struggles, and it was only because of this anti-imperialism that people could say “we are part and parcel of the struggle of black people against police brutality, we are part and parcel of the struggle of the Vietnamese against the Marines.” That was an analogy that the BPP actively championed, and championed it in such a way as to create that common cause. You couldn’t create that common cause, you couldn’t have draft resistance, without that analogy. You know, draft resistance in many ways preceded the development of the Party, but it did not precede the development of black anti-imperialism. Stokely Carmichael dragged SDS into draft resistance, and the Party took that position, and it really was in many ways in reference to the black anti-imperialism that the Party championed that the anti-imperialist folks who really led and developed the anti-war movement centering on the insurgent practices focused on draft resistance really were able to legitimate for themselves and their constituencies and supporters broader support. Because if you look at draft resistance in ‘64, ‘65, especially among whites, it was these white Catholic groups that were trying it out early on, they were branded traitors, they were treasonous, they were beaten in the street, and nobody cared. Draft resistance was central to the Party’s politics.

So that analogy with Black America, and in many ways with the civil rights movement, that the Party took up and espoused really was essential. You couldn’t have had the Black Panther Party without those kinds of international struggles.

To return to your first question: what exactly did the Black Panther Party mean by imperialism or anti-imperialism? The Party didn’t exactly mean anything by anything! The Party was not an academic discourse. Huey had some of those inclinations, and he was great theorist in many ways and tried to articulate certain things more clearly, but there’s no real scholarly precision – where these terms and ideas have precision is in their practice. They don’t have precision in a textual or definitional way. In fact, from leader to leader, from time to time, from city to city, over the course of the Party’s development – look at the Garveyite roots in New York versus the strident anti-pork chop nationalism of the Oakland Panthers – there were very strong and very stark ideological differences across the various chapters. There was no precise consensus, ever, on anything in the Party. What’s important to understand is the way that anti-imperialism helped constitute those practices.

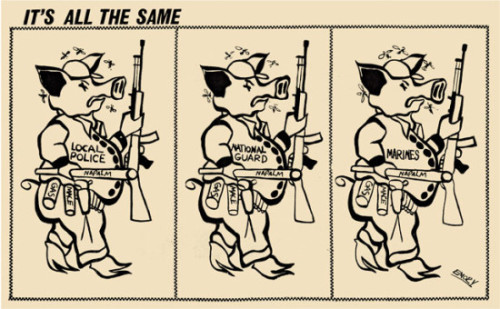

Emory Douglas really captured this idea of imperialism in a graphic that I reproduce in the book, of a pig stomping on a resister. There are three panels and they’re all the same, but the first is the police and Black America, the second is the National Guard and the draft resisters, and the third is the Marines and the Vietnamese. That analogy is crucial to the politics of the BPP. Without that analogy, they can’t carry out and sustain insurgency. They can only do so because they’re saying, “we’re part and parcel of this struggle that you all are part and parcel of, and a lot of you [our supporters and allies] all come out and help fight the court cases, feed the kids breakfast,” all of those activities.

BM: As you point out, the Black Panther Party saw their struggle as one of national liberation. But the Panthers saw their nationalism as fundamentally a revolutionary socialist one. Thus, the Party condemned the black bourgeoisie as collaborators, criticized those who adhered to a kind of “pork chop” cultural nationalism that essentialized blackness into an identity, and actively sought out alliances with other oppressed non-black revolutionary groups such as the Puerto Rican Young Lords Organization or the Mexican-American Brown Berets. They even worked with the Young Patriots, an organization of poor whites whose leader often wore a Black Panther button and a Confederate flag together. What was the basis of this particular kind of nationalism? Why did the Panthers place such a strong emphasis on working with other oppressed peoples? And how has this anti-capitalist nationalism, and the grounds for cross-racial solidarity in general, transformed since the 1970s?

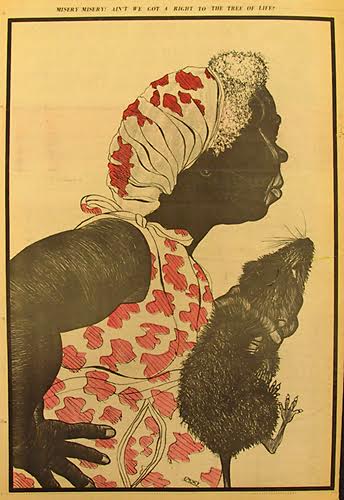

JB: The first two questions are about what is the character of the Panther nationalism and why was working with other oppressed people so important. Again, I think that different people thought about it in different ways. I argue that the Panthers are so well-known because that particular form of nationalism answered practical concerns. I was shocked when I started researching to find out many young black people were answering very similar questions in cities all around the country in a very sophisticated way. Have you seen Soulbook, the magazine that Bobby Seale worked on? I mean, they’re beautifully done, as well as striking and deep. Some of the most influential black revolutionary nationalists, like Harold Cruse and Harry Haywood, had major essays published there. And a lot of the ideas that you see in the party are all there! There’s also RAM’s magazine, Black America. This discussion was going on so powerfully. Everybody of the genre of the Panthers was looking at the civil rights movement and saying: “We can overcome. We can build power from below. Look, our people just dismantled Jim Crow. And yet here we are up in the ghetto, being beat up by the police. We can’t feed ourselves and we don’t even have any real access not only to money, but even political power and representation.” So the question became: how do we build that movement that really addresses the fundamental concerns that the civil rights movement at its heart was about? Civil rights practices targeted Jim Crow, segregation, and they also made claims for incorporation. But what people really cared about was freedom. And some part of freedom had been won, but lots of it hadn’t. In places like Oakland, the fact of how little of those changes had actually been made was pretty stark. Many sharp, young black people were asking this question in very sophisticated, organized, and forceful ways in this period. The Panthers found an answer that, again, and I can’t emphasize this enough, wasn’t an ideational answer. It wasn’t a perfect textual response; it was a practical response. Now those ideas of revolutionary nationalism, black liberation, etc., were essential to the practice. You couldn’t have had the Panther’s anti-imperialist practices, or sustained armed self-defense, without an anti-imperialist politics. It’s a cohesive, unitary cultural technology. You can’t have one without the other in any sustained way. So the ideas are essential to what the party is advancing. But the essential criteria is “how well can the party sustain disruption in this moment?” And a big piece of why they could sustain disruption in this moment is that they’re able to draw not only black support, but that they’re able to draw all kinds of people to their cause. I mean, who were the lawyers of the party? To pay those lawyers, you’re talking millions of dollars a day. Who are those lawyers? The sharpest, brightest minds from the top universities. But they were committed because they felt as part of the broader New Left, and anti-imperialist New Left, that there was no recourse for them in the United States as it was configured.

And how about the Young Lords, the Young Patriots, or the Red Guard and the I Wor Kuen? You had these immigrant communities that were struggling, trying to find their way. During the San Francisco State student strike, this dimension was taken to a whole new level, where groups were all able to say: “We’re all excluded. We’ve got a similar thing, with our own distinct and unique histories and a unique and distinct relationship here with the university. But there’s a commonality in that we’re excluded. And by working together across these divides, we can actually overcome some of that.” And the Black Panther Party, unlike many of the forms of black nationalism, was able to make those ties. The class politics was central to it. It’s not that all of the Party’s allies were working class or poor by any means – many of the lawyers, for example. But class politics was central to understanding what this global empire that all these groups were fighting against was, more broadly. There were moments when those kinds of anti-imperialist nationalism and Marxism were articulated more sharply. But it goes back to that three-part analogy in Emory Douglas’s cartoon. In the same way that you can’t understand the Party without anti-imperialism internationally ‒ it just wouldn’t have existed ‒ you can’t have a Black Panther Party without this analogy, i.e., that we’re all fighting in some way against a common imperialist enemy. That’s the central idea, the guiding and coherent thread.

PK: This question of alliances can bring us back to some of the points you were talking about earlier. One of the most provocative claims in Black Against Empire is the argument that repression did not, strictly speaking, lead to the destruction of the Black Panther Party. Indeed, in the face of such extreme repression (infiltration, fostering internal divisions, mass arrests, and assassinations), you argue that the Party actually grew. The Party was able to turn repression to its advantage by building these broad alliances with other radicals, progressives, and liberal sympathizers. Given the immense expansion, and increased sophistication, of the repressive and ideological state apparatuses in this country, as well as the transformation of mainstream liberalism itself, do you think this dynamic has changed? Can we still counter inevitable state repression in the same way, in moments of contemporary activism?

JB: You’re asking a contemporary question there. Let me start by reiterating the case that I make in the book and provide a little bit of quantitative support that wasn’t in the book.

There’s no doubt that during the period of harshest repression of the Party, it continued to grow considerably. One index to measure this is looking at the FBI records on the extent of growth of local chapters of the Party, or FBI records of the income of the Party, or coverage in the mainstream press like the New York Times. Some people say that the Party was media driven, but the reality is that media coverage follows the growth of the Party. But it followed it powerfully during the Party’s growth in 1970, when there was a peak in news coverage. At that point, the BPP sometimes averaged three stories a day, which is more than any single civil rights organization in the heyday of the civil rights movement. This was also the period when the federal government was going all-out in terms of repression, in coordination with local governments and police forces; but undoubtedly, the Party continued to grow powerfully in the face of repression. In other words, the Party’s greatest growth happened in periods of very intense repression. And in fact, almost all of the Party’s growth was in the face of intense repression. Very little growth happened antecedent to those kinds of dynamics.

The question, then, about the future is: what happens in the face of an increased capacity for repression? And I would add not just repression ‒ I sort of suggest this at the end of the book, but I read Gramsci very seriously. I see the sustaining of social order as being also very much about consent. Not only have the technologies for repression become more powerful and more targeted, I would argue moreover that the technologies of consent and mechanisms of concession have become more vastly powerful and ubiquitous. Think about Hollywood to internet to video games to Prozac to you name it. Absolutely, those are challenges.

There’s a quantitative change in repression and consent, sure, but there’s also a qualitative change. The forms of repression and the forms of consent are different, and so the solutions are themselves inevitably different. I don’t know how you prove this, other than just manifesting it in the world. There’s not really a proof for the claims that I’m about to make, but it’s my feeling, it’s my opinion, from having read history and seen plenty of moments where people felt fatalistic and felt like there was no way out ‒ where the things that had worked previously did not work. I think there has also been progress and that these same technologies and same technological developments are also tools that can be used, even if they are not panaceas. So no, the revolution will not be tweeted, and suggestions like that are really misplaced. But, I do think that what it comes down to is the cultural technology of insurgent practice. There are always, everywhere, in every social space, in every moment, strong and large institutional contradictions. There are always social divisions, whether they’re class divisions, relations of exploitation, whether they’re racial subordination, whether they’re patriarchy, whether they’re gendered divisions or cultural divisions or religious ones: human society ubiquitously generates relations of domination, subordination and division. And in doing so, it ubiquitously generates institutionalized divisions. And those divisions are always a resource for insurgency. Now, the divisions are not the same and the constituencies are not the same. The targets or tactics cannot be the same. The claims can’t be the same. But it’s my strong belief that there’s always the capacity for people to tap the power of disruption, and find ways to leverage those broader institutionalized cleavages in order to sustain disruption as a source of power from below.

PK: Alongside repression, the Party’s handling of gender and sexuality is often named as one of the central reasons for their decline. In fact, it’s one of the few arguments that brings together the social-democratic and insurrectionary factions – Elaine Brown and Assata Shakur have made remarkably similar observations about patriarchy in the party. Some have even drawn a causal link between the force of repression and the dangerous practice of patriarchy that was active in some quarters, showing how “misogynists make great informants.” While you and Martin admit that there were misogynistic men in the organization, and that patriarchy and male power were still operative like in the broader world, your book stakes two interventions into this history. First, you argue that the politics of gender and sexuality is a dynamic and contested question, and changes significantly from the founding of the Party in 1966 to the early 1970s, as evidenced in Newton’s own writings; but you also maintain that the Panthers consistently relied on women’s leadership and labor in maintaining some of their most effective survival programs. How do we square these two viewpoints: the critiques of patriarchal attitudes and structures within the BPP by leading female members, but also the more quotidian, but still revolutionary activism carried out by so many rank and file women Party members, and which often leaves little historical trace? Can we see a trajectory from the BPP’s gender politics to the leadership role taken by women and queer activists in current anti-racist struggles?

JB: Well, it was messy, right? And especially so in terms of gender politics. Ericka Huggins has told a story of going into a local Panther office and being told to wait as the women cook the meal and the men sit down and eat independently; then the women and children would wait in the other room until the men finished eating. That was often standard within a particular kind of black nationalism, a kind of misogynistic black nationalism. If you think about Ron Karenga and the US organization, that was built on a lot of those kinds of gendered nationalisms. And, let’s be honest: today when you open the New York Times, there’s white men in suits on the front page, and women in underwear selling perfume, jewelry, and clothes on the second. So there was nothing original or unique about the misogyny of the Black Panther Party. It was definitely a serious problem that had real consequences. It also was initially a masculinized kind of liberation project, in that it was an assertion of black manhood: “we’re going to stand up and resist the police.” Much of the early constituency, too, was young black men who were engaged in different activities of armed self-defense against the police. All that said, the Party took the question of other forms of oppression, including gender oppression, very seriously, not in the least various male leaders in the party – Huey Newton most significantly. Misogyny was central among those, and they sought to challenge and raise those questions. Those debates become really central in the Party. As we say in the book, young black women increasingly became the central, driving force of the Party. In fact, there’s a tremendous archival trace of this, which we describe. There’s many articles in the Black Panther newspaper that were written by women, although some pro-feminist men, raising questions of gender dynamics and gender liberation. So, while the Party came out of a milieu of widespread misogyny, both in terms of black activism but also society more broadly, those assumptions and those dynamics were challenged from fairly early on from within the Party, especially by women. They were incorporated into the Party’s politics and internal messages to such an extent that by 1970 or 1971, the BPP became the first major black political organization to endorse gay rights. I mean, that was just not happening very much in that moment, and it affected the Party’s daily political work. Many changes were incorporated into the day to day activity of the organization to reflect this stance.

Nothing was linear, straightforward or consistent across all bases, so it would be completely disingenuous to assert that the Party was at the forefront of women’s liberation. In some moments, however, it was, and the politics surrounding it were always interesting. Think about the New Haven trial for Bobby Seale: people think about the women’s liberation movement growing out of the struggle for civil rights, but to a large extent, the New Haven women’s movement grew out of solidarity and support for Ericka Huggins in New Haven. Many of the people that were a part of that mobilization were not out supporting Bobby Seale as a figure of male leadership; they only wanted to support Ericka Huggins. They didn’t want to support male leadership. These were very real divisions which were truly raw. But at certain times and places, the Party had an effective impact. Again, this wasn’t an overarching, coherent story, as many people document. There were all kinds of misogyny alive and powerful in the operations of politics of the Party.

BM: Okay, last question. It might also be a place to talk about some of the contemporaneity of questions of gender and sexuality, nationalism and internationalism, and some of the organizational questions that we’ve been bringing up throughout the interview. In one of the lines of argument near the end of the book, you give a summary reflection on the Panthers’ own decline as viable political movement: “No revolutionary movement of political significance will gain a foothold in the United States again until a group of revolutionaries develops insurgent practices that seize the political imagination of a large segment of the people and successively draw support from other constituencies, creating a broad insurgent alliance that is difficult to repress or appease.” In fact, however, over the past year, with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and connected organizations, we’ve seen a resurgence in large-scale protest activity centered around many of the issues the Panthers themselves faced: police brutality, entrenched racism in social services, and urban poverty. Do you see this rise in activism as a significant challenge, with the ability to proliferate and develop new insurgent practices? How does this new wave compare to the historical movement you’ve studied, and what are some resources that serious study of the heterogeneous currents of the Black Power/Long Civil Rights era could provide us with now?

JB: To start, I want to stress that this is an exciting moment historically. But so far, I don’t think that Black Lives Matter is really comparable, in terms of the scale of articulation and mobilization, with the Black Panther Party. I’m not sure if we can call it a movement yet. I think in many ways it’s parallel with the call for Black Power and the question that call for Black Power posed. When I talked about RAM, the group around Soulbook, and those organizations all around the country that were asking the question of “how do we build a movement that challenges police brutality, that challenges ghettoization, that challenges exclusion from electoral politics?” I think that’s the kind of moment that Black Lives Matter represents right now, and poses these questions. It’s also tied to the questions posed by Michelle Alexander, with the recognition of the New Jim Crow. How do you have the persistence of a very strong and very statistically clear system of racial subordination in this post-racial era, where race supposedly doesn’t even exist? Alexander actually provides a framework for thinking about that question, especially around the War on Drugs and penal sentencing, and how a color-blindness came to constitute a new form of persistent racial subordination, and we can call that the New Jim Crow.

I think what Black Lives Matter does, is that it very specifically attaches the effort to dismantle the New Jim Crow to this front of police brutality, as it is experienced and lived. Now, what has happened in the past few years is that there’s a piercing of the veil, to use W.E.B. Du Bois’s phrase. In Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois talks about Black America living in a different world, one that white America cannot see or access. In turn, Black America lives out this double consciousness: it lives both behind the veil, but also experiences what’s going on in the dominant society. With the numerous recordings of these instances of police brutality, captured through relatively recent video technologies, there has been a piercing of the veil, as it were. But let’s be clear: hardly any black person living in the United States is surprised by these videos; certainly not many poor black people are surprised, or even people who work to an extensive extent in black communities.This is not new, it’s been going on for decades. There is a kind of policing of black communities that is very much akin to what Frantz Fanon talks about in Wretched of the Earth: the rule of the rifle butt and bayonet. It doesn’t follow the order or rules of civil society – it’s a rule of force. Those are the conditions in which many communities have lived under and have interacted with police for decades.

What happens in this moment of post-racial mythology is that since there are so many people who are not living in and insulated from life behind the veil, when that veil is ruptured by this video footage of what it means to be black in America – to be killed with impunity, with no recourse in the justice system – when that’s exposed, it shakes things up. Some destabilization happens there, and it’s something potentially comparable to what was happening in the early civil rights movement, in the sense that there was a systemic decoupling with the decline of the cotton economy and a breaking of the national consensus on Jim Crow – but there was also news footage, you could broadcast these violations of civil rights. But the news footage itself did not dismantle Jim Crow. The video recordings of brutal police murders will not dismantle the New Jim Crow. And already, there has been a coordinated, powerful federal and municipal response to suture the wound – a concerted response to try to show that everything’s okay. Keep this thing out of the news, and let’s reassure ourselves that America is actually okay. Authorities at the local level, together with clear national coordination, are trying to fill this hole in the veil and are figuring out institutional responses. But there’s very little motivation on the part of those authorities to actually dismantle the New Jim Crow, and very little evidence that they will do much to dismantle it.

The way that history works in my reading – if you think about Michels and the Iron Law of Oligarchy – it’s not just that the rich get richer, but that the powerful become more powerful. Why? Because as you accumulate and gain institutional power, you have an increased capacity to set the rules of the game. So if you’re racing, and you’re both doing developmental politics and doing the best you can with what you have, the people ahead of you in an exploitative, polarized, oppressive relationship are always going to get ahead faster. Important junctures and changes in that dynamic are sometimes driven by technology, but more often are catalyzed from below, when people have figured out how to make business as usual impossible, and how to sustain disruption as a source of power.

BLM has not figured out the last part: how to sustain disruption as a source of power. The biggest growth of the movement, which we can see in preliminary quantitative analyses from event data, came with the death of Michael Brown. Of course, the phrase itself came with the death of Trayvon Martin, but you really got a national movement with Mike Brown. Eric Garner was killed before Brown, but his case received more attention as the movement erupted out of Ferguson. And I believe that Ferguson was such a big deal because it almost looked more like the old Jim Crow. “You guys are going to have the audacity to nonviolently protest this thing? You’re black, get your ass in place.” They brought out tanks and military gear, and proceeded to beat the hell out of the protesters who were doing basically what they had learned and everyone’s supposed to do – the nonviolent, civil rights protest practices. They treated the nonviolent protesters in Ferguson much like how people had been treated in the heyday of the civil rights movement. And there is a strong national consensus that those actions by law enforcement authorities are not tolerable, and a national movement emerged. But what happened subsequently?

When you look at those Eric Garner mobilizations in New York, both after the initial incidents and again after it was regenerated by the the uprising in Missouri, there was a very big wave of protests following the failure to indict in December. People were asking: “how is that possible, we have a video of Garner saying I can’t breathe, and you won’t even take it to a court to find out?” This is precisely a rupturing of the veil, and lots of people were mobilized. And what do they do? They shut things down, disrupted daily activities, like the planned actions in Grand Central Station: “We’re going to have a die-in in Grand Central Station everyday until we get justice.” How did those events unfold? Well, on day one, there’s real support, because the mobilizing event is fresh in people’s minds. On day two, there’s still support, but less so. And it progressively decreases from there. By week three there’s almost a consensus reaction of “get out of my way, I’ve got to get my kids to school and I’ve got to get to work.”

It’s obvious in this case that you have disruption that is not coupled in any coherent way with the actual claims of the movement, and does not succeed in leveraging those broader institutional cleavages. There’s all kinds of people upset about all kinds of things, and all kinds of people who think that the way that Black America is being treated at the hands of the police and the legal system is quite alarming and a big problem. But no cultural technology exists for making business as usual impossible in a way that draws all those folks on board, to the point where they’re saying: “and when we get repressed, that repression feels just as important to me as the initial killing felt to me in the first place.” It is not as threatening to you when those activists are trying to shut down Grand Central and everyone else is trying to go about their daily business. It’s not like you’re outraged and people are circulating videos about the activists three weeks in, blocking traffic – those people are being taken off in handcuffs. But people need to be outraged. The only way Black Lives Matter will become a movement, and the only way that we’ll dismantle the New Jim Crow, is if we develop the cultural technologies, the insurgent practices, the repression of which would be just as threatening as the initial events themselves.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine