The emergency session of the Occupy Philly General Assembly this past Thursday decided, at around 10PM, to immediately move from Dilworth Plaza, where Occupy Philly is currently grounded, to Thomas Paine Plaza. When the proposal passed, everyone broke into smaller groups, rushed to grab whatever was around, and began moving to the other side of the street. Soon after, the police arrived, confusion descended, and, not having decided on any plan ahead of time, we spontaneously broke into three groups: the first regrouped back at Dilworth, the second was left at Thomas Paine, and the third decided to storm City Hall. At the end of it all, we were forced to abandon our objective, withdraw back to the original encampment, and rethink the whole affair.

The emergency session of the Occupy Philly General Assembly this past Thursday decided, at around 10PM, to immediately move from Dilworth Plaza, where Occupy Philly is currently grounded, to Thomas Paine Plaza. When the proposal passed, everyone broke into smaller groups, rushed to grab whatever was around, and began moving to the other side of the street. Soon after, the police arrived, confusion descended, and, not having decided on any plan ahead of time, we spontaneously broke into three groups: the first regrouped back at Dilworth, the second was left at Thomas Paine, and the third decided to storm City Hall. At the end of it all, we were forced to abandon our objective, withdraw back to the original encampment, and rethink the whole affair.

Some called it a skirmish, others an experiment, but I think we have to recognize that it was a defeat, albeit a necessary defeat – one that, if confronted directly, might paradoxically prove to be our greatest success. Part reflection, part autocritique, what follows is my attempt to think through the events of that night.

State of Emergency?

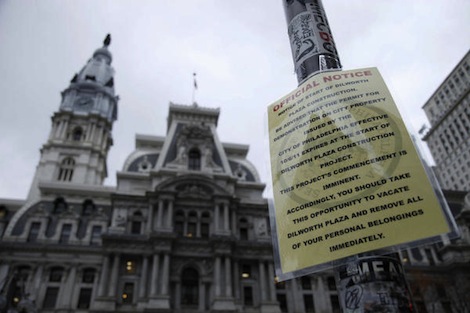

An announcement was made, before introducing the proposal to move to Thomas Paine Plaza, reminding everyone to stay calm, to avoid spreading rumors, and to stymie the circulation of fear. Immediately afterwards we were told that eviction from Dilworth Plaza was imminent. “They could come at any moment: tomorrow morning, tonight, or even right now.” Indeed, the City had posted ambiguously-worded yellow posters at the occupation reminding us that our permit will expire as soon as construction begins, that construction was in fact “imminent,” and that we should all take this opportunity to vacate. So an abridged General Assembly hurriedly met earlier in the day to draft a proposal, the evening meeting was – perhaps unwisely – dubbed an “emergency session,” and we were repeatedly reminded throughout that we would have to vacate the room in which we were gathered (generously made available to us by the Friends Center) by 9PM. Little surprise that a pervasive atmosphere of urgency, alarm, and even distress filled the air.

But the rumors about immediate eviction were just that. It was the city itself that had deviously circulated the threat of an imminent confrontation, falsely announced that it had already given the notice, and connivingly spread the assumption that any such crackdown would be legally justified. And we bought it. The looming sense of ominous disaster set the tone for the entire assembly: we rushed through the proposal, truncated the stack, tabled amendments, encouraged speakers to be brief, reverted heavily to straw polls – in short, we did everything in our power to move as quickly as democratically possible that night. And this would have all been justified had the rumors been true. But they weren’t.

There was no conflict around the corner, no official notice of eviction, and no legal legitimacy for such an action. After the whole affair, we finally learned – much to our chagrin – that those yellow posters were not really official eviction notices. The city had lied. Of course, we didn’t know, so the spectre of eviction weighed heavily on us all that whole night. It was used to shoot down a friendly amendment postponing the move until the next morning, when we would have more support, organization, and visibility. It was used to justify the argument that if we failed to move immediately we would forefeit the initiative. It was used, in sum, to convince us that the only thing we really could do was respond as quickly as possible – even if that meant responding without any real preparation.

To Ground Our Politics on Revenge?

A few days prior it was discovered that the so-called “Reasonable Solutions Working Group” had entered into secret negotiations with the City. The group, which already had a rather sordid history of red-baiting, collaboration, and general uncooperativeness, made it clear that they would no longer accept the decisions of the General Assembly. So in direct opposition to the decision made last week to hold our ground, “Reasonable Solutions” chose to act alone by asking the city for a permit for Thomas Paine Plaza. The sovereignty of the General Assembly was immediately undermined and the weakness of the occupation itself as a form of struggle was made painfully apparent. Now everyone knew for certain, without the shadow of a doubt, that there were not only enemies in our own ranks, but there were serious contradictions at the heart of the movement.

This, of course, was on everyone’s minds as they walked into the Friends Center Thursday night to discuss the emergency proposal. But more than confusion, disappointment, or even anger, there was a palpable desire for revenge. Several occupiers made the explicit connection: voting to occupy Thomas Paine Plaza tonight would preempt “Reasonable Solutions.” They undermined us, now we will undermined them. Wild applause. To tell you the truth, I can’t say I wasn’t among them. We felt betrayed. But instead of interrogating this betrayal further, instead of trying to rationally understand what this said about the cohesiveness of our movement, or the political effectiveness of the General Assembly, or the nature of the encampment as a viable tactic, we let our instincts take over. Too afraid to find a solution to the deeper causes of this betrayal, we hoped to simply efface it by smothering the affair as quickly as possible.

For the Union Makes Us Strong?

The move to Thomas Paine Plaza was in part motivated by the admirable desire to build stronger connections to the unions. As we have mentioned elsewhere, for the movement to succeed, it is obvious that it will have to form deeper ties with other sectors of the working class. This means both the hyperexploited workers that always go unrepresented as well as those more traditional sectors of the class that continue to be organized in the trade unions. It was argued that holding Dilworth Plaza, and therefore indefinitely delaying its proposed renovation, would actually prevent thousands of jobs for unionized workers. If we moved, the argument went, it would show our solidarity with those workers in way that might bring them closer to Occupy Philly.

The same argument reappeared Thursday night, but this time, it was formalized in a letter read aloud by the Labor Working Group, and supported by several union representatives in attendance. We were now told that the unions would not only support the move, but that they would even be willing to help us move, and that they might even call a march in solidarity. This, of course, was never a guarantee. But many of us took our desires for reality by assuming that the unions would all be behind us when we made the move. As though all we had to do was shine the bat-signal into the sky for all the unions to triumphantly appear in the middle of the night. Predictably, of course, there were no unions in sight when we did make that move later that night.

First, while we must draw ourselves closer to unionized workers, we must bear in mind that the rank and file is not the bureaucracy. While we might be able to trust our fellow workers in the unions, we should never delude ourselves into trusting those who manage those unions. Second, we have to ask ourselves what solidarity really means. Is it enough for the unions to issue a statement supporting our move? Is it enough for them to tell us that they would be open to speaking with us about future actions? Or must we somehow try to make solidarity material again? We have to clarify the wording of our proposals. And this was, in fact, done that night. We would make the action not with the unions, as was falsely stated in the original, but we would do so with the expected support of the unions. Sadly, this was passed off by everyone, including the facilitators, as a mere changing in wording, one that would not in any way make a substantial change to the content of the proposal itself. But, in reality, this was a first step toward rethinking the practice of solidarity. The unions will support us only when they bring their workers out in union colors to stand by us. Until then, all we have is our words, not real solidarity. Why should we give so much weight to the arguments in support of the unions when the unions have not given any support to our arguments? We need to stop fetishizing the unions.

What Are Our Enemies Thinking?

After the proposal to move was passed we all set to work. I joined the Library Working Group in filling crates with books, moving bookshelves, and securing all the literature. A few of us made a kind of library caravan from one plaza to the other, victoriously crossing the street, to the other side, filled with a sense of general excitement. Just as we got there we saw a police van drive up, sirens ablaze, and stop right in front of the Plaza. We all stared. Then came the frenetic cry for the Legal Working Group. Legal ran over, spoke with the police, and we stood by as more policemen began to amass on the Plaza. There was general confusion when it became clear that the Police were going to destroy everything we had just moved to Thomas Paine Plaza. Some said we should hold the new Plaza, some said we should return, some thought we should escalate the conflict by storming City Hall. In brief, the mere presence of the police was enough to throw the entire operation into disarray.

But why should it have? Shouldn’t we have expected the police to arrive? Shouldn’t we always expect them to oppose all of our actions in some way or another? In other words, why should the presence of an expected element cause so much disorder in the equation?

In retrospect, it is simply astonishing that none of the concerns raised during the several hours of the General Assembly directly mentioned the possibility of having to face the police that night. None of them asked what we should do in case the police arrived. None of them wondered if there were any contingency plans. In fact, almost no one was seriously thinking about what our enemies might be doing at that moment. We were just staring at our own camp, deciding whether we should move to Rittenhouse or Thomas Paine, rather than talking about what might be going on the camp of the opposition, rather than thinking two moves ahead.

It should be admitted, however, that the police were themselves unusually unprepared that night. Several occupiers recall how the police seemed uncertain about how to proceed, that many of them were almost entirely unaware that we had made a decision to move the entire camp. But, at the end of the day, even though the police were relatively unprepared, the truth is that we were even more unprepared. And that cost us an opportunity.

I think it’s safe to say that in large part the peculiar police détente at Occupy Philly lulled many of us into a sense of passivity. We hadn’t experienced crackdowns like those in New York or Oakland. We were given a permit, given our space, and largely left alone. The consequence was that we simply assumed such a state of affairs would continue into the future. We were unopposed when we entered Dilworth so why should they oppose us when we move to Thomas Paine? One might say we mistakenly took an exceptional case for a general condition.

Perhaps the most important consequence of that night, however, was this changed attitude towards the police. It immediately dawned on us all that henceforth we had to think about what we would do if we were in the police’s shoes, we had to study their position, we had to plan for all possible responses on their part, and we had to prepare responses to their responses. We can’t afford to take another action without anticipating the actions of the forces of order.

Who’s Got The Map?

As we relocated to Thomas Paine Plaze we were met by various occupiers trying to help rebuild the camp as coherently as possible. With hundreds of occupiers rushing from one plaza to the other, it was imperative that we had some people organizing the whole process, to let everyone know were the new Library, for example, would have to be constructed, where the Information Working Group would have to resettle, where all the tents would have to be erected, and so on. But while some occupiers had already sketched out a map to help reconstruct the camp, few knew about it, and what’s worse, the map itself seemed to be missing. So the arrival of the first wave predictably caused a bit of confusion. “Should we send them back until we figure out where everything goes?” Impossible. So the waves kept coming, the disorder grew, and quite a number of occupiers didn’t know where to go. The library, for example, ended up in the wrong place. But before we could relocate it, the police arrived.

This situation was unsurprisingly aggravated once they entered the picture. First we decided to move everyone from Dilworth to Thomas Paine to fortify the newly captured position. Then, when the Police gave the order to disperse, many began to move everything back from Thomas Paine to Dilworth. As I already mentioned, one group stayed at Thomas Paine to decide what to do, another regrouped back at Dilworth, and the third decide to storm City Hall. So instead of coming together in a common refusal, the movement shattered into several isolated groups. Only after the dust settled, after are defeat had been confirmed, did we reconvene again as a totality.

If there is anything we learned from that night, it’s that even the most seemingly simple operation – moving one camp just across the street – requires significant preparation. A clear set of plans has to be composed before the action, it has to be distributed to all participants so everyone can operate in harmony, and it has to include contingency measures. Everyone has to agree ahead of time, for instance, that if the police arrive, we will hold our ground. Instead, that decision had to be made on the spot, within various affinity groups, and by then, everything was irreparably split. I’m not saying we shouldn’t make these kinds of immediate decisions on the spot, as it were, but only that everyone has to be prepared – and everyone must expect – to make them. In other words, we have to pre-organize the space for successful spontaneous action.

A Meeting of the Tribes?

My immediate sense is that while the occupation as a whole suffered from confusion, there was significant organization, efficiency, and celerity among the individual working groups, caucuses, or affinity groups that compose Occupy Philly. Those involved with the library, for instance, ferried books, shelves, crates, tables, and posters – in fact the entire library – from one Plaza to the other in just fifteen minutes. Then, when the order was given to disperse, we determined our options, discussed the choices before us, and quickly made the decision to move everything back from Thomas Paine to Dilworth – some of us making the move while others went to get a van in which to secure all the material in case of an immediate eviction. The books were then loaded into the van, unloaded at another site, and the group reconvened at Dilworth. A small endeavor, no doubt, but one which speaks to the effectiveness of small groups composed of individuals who are accustomed to working with one another.

The problem, however, seemed to be while there was much cohesive efficacy within each of these groups – and the library was only one of many – there was little inter-group cohesiveness. Despite its many success, Occupy Philly, it appears, has not yet discovered a way to make affinity groups work with each other in moments of tension. Perhaps we need to look to different forms of organization, like the “Spokes Council” model, which has been tested at other occupations. Or perhaps we have to look beyond the occupation as tactic. It may be that the very structure, or logic, of the occupation tactic has itself foreclosed the possibility of productive inter-group relationships. I think, in Philly at least, it may be time to move on to something else.

Lost Illusions

It seems Thursday night was a necessary defeat. It disabused many of us of certain illusions, it reframed our relationship with the state, and it changed our broader understanding of this movement, its relationship to specific tactics, and the contradictions within it. There is no question that Thursday represents an implicit rupture in the trajectory of the movement here in Philadelphia. Our task now, I think, is to make it explicit. The worst thing we can do is – to paraphrase a suggestion made Thursday night after the police withdrawal – to regroup and try to take Thomas Paine again in the morning. This would be nothing other than a doomed compulsion to repeat. It would mean ignoring our mistakes by trying to efface them, it would signify a failure to exploit the numerous opportunities that have emerged from this defeat.

On May 15, 1848 an immense demonstration was organized in Paris in response to the precipitous degeneration of the revolution that had begun just under three months ago. When the Provisional Government was declared on February 25, 1848 in the Hôtel de Ville, the proletariat saw a chance to deepen their autonomous power. Things turned sour, the revolutionary clubs were harassed, elections were invoked to undermine the momentum of the opposition, and now, finding themselves on the verge of defeat, the working class decided to make a show of their power. Confused, unable to interrogate the reasons behind their continuing defeat, unwilling to confront the changed conjuncture, and fearing an imminent crackdown, they made the last-minute decision to invade the National Assembly, storm the Hôtel de Ville, and announce a new, this time more revolutionary, Provisional Government in the very same room in which the first one was declared back in February. All we had to do, they thought, was repeat it again; this time, with new people, it will be different. It wasn’t. They lost that night, and they would have lost even if they had successfully held City Hall – the historical conjuncture had shifted in such a way that the entire tactic had to be changed.

I think it’s time we changed ours.

Salar Mohandesi is a graduate student at UPenn, and an editor of Viewpoint.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine