By the 1990s it appeared that Argentina’s working class, once one of the best organized working classes in Latin America, had been sorely defeated. The military dictatorship of 1976 to 1983 targeted leftist and labor activists with brutal repression and began the implementation of neoliberal economic policies. Of the many legacies of the dictatorship were the disintegration of social ties of trust and solidarity, and a generalized fear of participating in collective action. Under Menem in the 1990s, the working class saw its power decline even further, as laws were put into place encouraging labor “flexibilization” and limiting workers’ rights to organize. The country’s central labor union continued supporting Menem because of his Peronist affiliation, leading to internal conflict and eventual fragmentation. Neither the unions nor the political parties recognized the full extent of the transformations brought about by the shift to a post-Fordist economy, and continued organizing in ways that assumed the factory worker as the privileged economic and political actor. For the most part, they ignored the growing mass of unemployed and informal workers, and when they did attempt to incorporate their struggles, it was always subordinate to the formally employed. These limitations caused both the unions and leftist political parties to lose legitimacy in the eyes of much of the working class. As the newly poor and unemployed found themselves abandoned by traditional political institutions, they turned to multiple forms of investigation to understand the conditions in which they found themselves, and to develop more effective forms of action and organization. These processes of investigation were fundamental for the formation of movements of the unemployed across Argentina in the 1990s, and, in some cases, point to a different way of doing politics that places inquiry at the center of its practice.

The “unemployed” are far from a homogeneous group. Organizations of the unemployed bring together people with different experiences of work and unemployment, such as laid-off factory workers; those with temporary or part-time jobs; women occupied with household work, whether paid or unpaid, in their homes or the houses of others; and people living off of illegal activity, informal jobs, government subsidies, micro-loans or some combination of all of these. One of the first tasks for inquiry was to understand the composition of this broad category of the “unemployed.” These investigations have employed multiple methods, from surveys and censuses in the neighborhoods most affected by unemployment, to research and analysis of the structural causes of unemployment, to workshops and discussions on the effects and experiences of being unemployed. In most cases, these inquiries were initiated by the unemployed themselves, with clear political objectives. Without a shared workplace and clear identity as “workers,” there is no obvious site or subject for a “workers’ inquiry.” The heterogeneous nature of “the unemployed” makes organization difficult; commonalities between the unemployed cannot be taken for granted. Therefore, part of the process of inquiry involves identifying shared problems and experiences, needs and desires, working toward the creation of a common space and collective subject.

One of the demands from the early roadblocks, after winning initial unemployment subsidies in 1996, was for the movements themselves to be allowed to conduct the censuses in their neighborhood to determine how many unemployed families needed benefits. 1 The organizations that were most successful with this strategy were the large organizations of the unemployed, affiliated with independent trade unions that had the resources to conduct extensive surveys in broad territories of the urban periphery. Besides expanding the reach of unemployment benefits, this had the effect of taking power away from clientelist networks, in which local politicians and representatives of political parties used the distribution of benefits to gain political support and increase people’s dependence on them. Thus, the movement’s use of censuses not only allowed them to gain material benefits in the forms of unemployment subsidies for neighborhood residents, but also encouraged self-organization in the neighborhoods, wrestling power away from clientelist networks and other hierarchical structures and allowing the movements to create new territorial networks of their own in certain neighborhoods.

These organizations undertook territorial inquiries into the conditions of life in the neighborhoods where they were attempting to organize, largely focusing on objective conditions around which collective demands could then be made: lack of potable water and sewage, gas and electricity, food. This research aimed to document the extent of unemployment and its effects, while at the same time assuming that a return to the full employment of the Peronist era was possible and desirable. Thus, it failed to recognize the importance of other forms of labor, the multiple ways in which people maintain their livelihoods, as well as the new subjectivities and desires – subjectivities formed outside of the workplace, and desires for lives not defined by work. Although some of these organizations did attempt innovative models of territorial organizing, for the most part they continued to privilege the subjectivity of the male worker, marginalizing women, youth, and migrants, who were less likely to fit the traditional model of the working class.

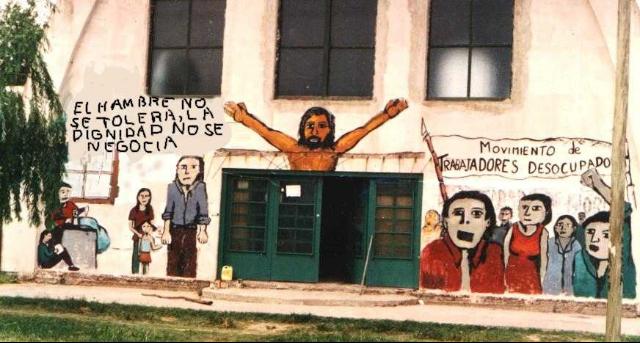

Of the wide range of movements of the unemployed that emerged in the 1990s across Argentina, those that remained autonomous from political parties and trade unions, the Movements of Unemployed Workers (Movimientos de Trabajadores Desocupados or MTDs), were the most likely to prioritize investigation and knowledge production. The MTDs, unlike most other movements of the unemployed that became integrated into pre-existing political parties or unions, recognized that old categories and forms of organization were no longer sufficient for the current moment. Although also starting with scientific-objective inquiries, these groups soon realized that understanding the objective conditions was not enough for effective political organization. They began focusing on the more subjective aspects of unemployment and using investigation itself as a tool for self-organization. Besides understanding who was unemployed and why, activists sought to identify responses to unemployment and the obstacles to the organization of the unemployed. They were committed to investigating the changes in class composition, as well as the new forms of production and exploitation. Their inquiries emphasized the subjectivities and desires of the unemployed, their ways of living and forms of self-organization.

New Subjectivities through Inquiry

For the MTD La Matanza, based in the municipality of La Matanza immediately to the west of Buenos Aires, experiences of collective investigation and knowledge production were key to their formation as a movement, and to the establishment of a school and a cooperative. The movement began in 1995, as neighbors came together to protest rising electricity and gas prices. Then began processes, at first informal and later more formalized, of investigation into life in the neighborhood. These inquiries led them to identify unemployment or lack of formal employment as the common problem behind many of their complaints. They began more focused reading and study groups, inviting local intellectuals to give workshops, to better understand the causes of unemployment and develop a critique of neoliberal capitalism. They further researched the effects of unemployment and neoliberal policies in their neighborhood with more interviews and discussion groups. As conditions worsened, these processes of collective investigation then took to the streets in the form of roadblocks to demand services and benefits. The MTD was constituted around the slogan “work, dignity, and social change.” 2

The MTD La Matanza emphasizes the importance of a collaboration with social science students from a local university for understanding the subjective effects of unemployment. They identified three responses to unemployment: 1) those who maintained feelings of individual guilt and responsibility with regards to their unemployment; 2) those who looked to the state to resolve the problem, either through financial assistance for the unemployed or jobs programs; and 3) those who started to create forms of self-managed cooperative work and mutual aid to resolve the problems of unemployment themselves. The focus on the subjective aspects of unemployment highlights the feelings of guilt and isolation, and the breakdown of ties of solidarity and support that had previously been based around the workplace. Since both of these factors make organizing extremely difficult, the MTD began to directly address those questions, working on challenging those feelings of guilt and creating new social bonds of trust and solidarity outside of the workplace.

Through these processes of investigation, members of the MTD began to value their own knowledges and capacities, overcoming some of those feelings of guilt and inferiority. They later started their own radio program and publishing house, which served as ways for the unemployed to tell their own stories and recover confidence in themselves. Understanding the structural and permanent nature of unemployment/precarious employment, in 2001 they decided to start a worker-managed bakery and textile workshop, instead of demanding jobs from the state or private enterprises. Here they ran into additional problems, all stemming from a capitalist subjectivity that accustoms them to listening to authority and avoiding making decisions and taking responsibility. Through workshops with social psychology students, the MTD began addressing these problems, learning how to make decisions collectively and how to work without the presence of an authority figure. Recognizing how deep these subjective obstacles to self-management run, the MTD decided to place further emphasis on education and formation from a young age, starting a kindergarten and other programs for children in order to produce “liberated subjects.” Along with a number of adult education programs, these activities focus on the creation of non-capitalist values and enhancing capacities for self-management.

The MTD of Solano, founded in 1996 in the southern region of Greater Buenos Aires, goes even further in placing investigation and education at the center of their practice. Critical of leftist practices that reproduce capitalist hierarchies and dominant subjectivities, the MTD Solano aims to produce new values, subjectivities, and social relations. For them, inquiry is also an attitude, a disposition to experimentation and openness to the unknown and unexpected. This commitment to inquiry has led to new theoretical insights, understanding unemployment not simply as exclusion but rather as a specific form of inclusion. They recognize that forms of labor have changed, and no longer correspond to the Peronist ideals of full employment and mass factory work. Precarity and unemployment are not temporary anomalies, but are central to the current form of capitalism. On the basis of this analysis, members of the MTD Solano do not call for inclusion or more jobs, like many of the organizations of the unemployed, but instead focus their energy on creating new forms of living that are less dependent on capitalist institutions.

The MTD Solano understands investigation in a broad sense to include the formal workshops and writing activities carried out by the movement, as well as the learning that takes place in roadblocks and other actions: moments of self-reflexivity, discussing actions and their consequences, learning to make decisions collectively and relate to one another differently. They describe their assemblies as moments of collective thought, beyond the discussion of tactics and strategies, moments for developing new ways of thinking and creating new forms of sociability that challenge the dominant individualism. They emphasize the importance of socializing knowledges and skills, allowing people to learn from each others’ experiences, develop their own capacities, and take on more responsibilities within the movement. 3

Two of the group’s main activities over the last eight years have been the creation of a collective farm and a community health clinic. The projects challenge dominant discourses about food and health, attempting to create sustainable ways of living that are less dependent on the state and market. They have investigated organic food production and alternative crops with the help of Argentinean campesino and indigenous movements and Cuban agronomists, learning what crops are most suited to their plot of land and how to deal with the effects of climate change. The health clinic promotes alternative visions of mental health, working with whole families and communities to solve problems instead of relying on psychiatric medications. They incorporate lessons from different indigenous and alternative medicines into their practices. These projects are based not only on learning new skills and techniques from other movements and communities but also on investigating the conditions of the neighborhoods where they work. This research allows them to identify common problems and needs, as well as the forms of self-organization and collective survival already being put into practices, to recognize and strengthen the emancipatory aspects of those practices.

What the experiences of these two MTDs point to is the productive and political capacities of inquiry: the research process itself plays a fundamental role in the production of new subjectivities and social bonds. Investigation into the causes and effects of unemployment challenge any notion of unemployment as an individual problem, helping people overcome feelings of guilt and personal responsibility for not having a job. Active participation in these processes of investigation also plays an important role in building unemployed peoples’ confidence in their own capacities and knowledges; it teaches them new skills and helps form group cohesion, creating a shared experience among the participants. Moreover, this disposition toward inquiry implies a different way of doing politics, one which does not assume a predefined subject or path of action, but instead emphasizes the production of new social relations and experimentation in forms of living and organization.

At the same time as these movements of the unemployed were emerging in the mid-1990s, Colectivo Situaciones was forming in Buenos Aires. Through intense collaborations with the MTD Solano and other social movements, Colectivo Situaciones began elaborating the concept of militant research/research militancy against both academic research and traditional leftist activism. Against academic research that proclaims objectivity, the neutral observation of a pre-defined object that often does not go beyond sociological description, and mainly serves the career interests of the author. Opposed to traditional forms of activism with predetermined “revolutionary subjects,” forms of action and organization, aims and conclusions. Both academic research and traditional activism construe themselves as exterior to their object; the researcher and the activist both pose as experts, outside of the struggle. Militant research, on the other hand, is immanent to the situation at hand. Colectivo Situaciones discusses militant research as a process of love or friendship that radically transforms all of those involved, that produces something in common. The militant researcher does not pretend to be objective, but rather values the production of knowledge for struggle. There is no purism of knowledge; investigation becomes risky, any easy distinction between the researcher and the researched breaks down. 4

Militant research is more than a different form of research; it is also a different way of doing politics and understanding the relationship between the two. As Holdren and Touza state in their introduction to the work of Colectivo Situaciones: “Research militancy does not distinguish between thinking and doing politics. Insofar as we see thought as the thinking/doing activity that de-poses the logic by which existing models acquire meaning, this kind of thinking is immediately political. And, if we see politics as the struggle for freedom and justice, all politics involves thinking, because there are forms of thinking against established models implicit in every radical practice – a thought people carry out with their bodies. Movements think. Struggles embody thought.” 5 We can see this different way of thinking and doing politics and investigation embodied in the practices of the MTDs.

This new form of politics took on unprecedented dimensions in the wake of Argentina’s 2001 economic crisis. People began creating ways not only of surviving the crisis, but also of building new forms of social relations and solidarity in the clear collapse of old forms of organization. New political subjects, with different histories and practices, demands and hopes, took the stage, leading ultimately to a wave of destituent action in 2001 under the banner “they all must go.” New forms of living, which the MTDs were already experimenting with, began to spread as unemployment reached unprecedented levels and more and more people sought to sustain their livelihoods outside of the labor market. Nationwide barter networks emerged, where participants would directly trade goods and services using alternative currencies, or sometimes without the mediation of money at all. Workers across the country took over factories abandoned by management to run them as worker-managed cooperatives. Neighbors in urban areas began meeting in horizontal assemblies to discuss and find collective solutions to common problems. 6 These practices overflowed traditional forms of organization, catching them off guard and leaving them incapable of responding to the situation. These new forms of organization, with little participation from the traditional Left, were largely responsible for the protests in December of 2001 that overthrew the neoliberal government. In this context, the investigations of the MTDs and Colectivo Situaciones turned to the these emerging new forms of organization and subjectivities, exploring the collective desires behind them. Investigations uncovered a generalized crisis of representation marked by a widespread loss of faith in representative bodies, as well as all forms of representative decision-making. They announced the emergence of new subjects desiring autonomy, with enhanced capacities for collective decision-making and control over common affairs. Inquiries sought to understand the contradictions and limitations of these processes, as a moment of self-reflection for participants, while creating more opportunities for collective experimentation and building relationships between different experiences.

Investigation Today

These experiences of inquiry provide some important insights into the political potential of investigation today:

- Research must continue into the changing technical composition of labor, including the specific roles workers play in the productive process and the sociological makeup of the working class, but also the ways in which people are exploited, their level of awareness, and other subjective qualities. Research should also explore the multiple divisions within the working class.

- This inquiry, however, must move beyond the workplace: it is no longer a question of taking investigation into the factory but of researching those forms of exploitation and capture that occur throughout the different time-spaces of our lives. This must include the different forms of informal labor that are often unrecognized, as well as the household labor carried out mostly by women. In a broader sense, it must include all the ways in which value is extracted from social cooperation and common resources.

- Inquiry should contribute to the recomposition of struggles by highlighting shared experiences and problems, goals and desires. This research process builds awareness and understanding of the multiple forms of exploitation that define contemporary capitalism, and the process itself serves as the beginning of the constitution of a new collective subject.

- Investigation must also look at those forms of self-organization, including forms of survival and mutual aid developed on the margins of capitalist relations of production, which often overflow and move beyond the organizations and institutions claiming to represent the working class. Inquiry serves as a space for self-reflection for these experiences, to allow them to deepen and grow and connect with one another.

- This investigation is necessarily a collective process. While individuals with relationships to universities often engage in these collaborations, they are fundamentally different from academic forms of research based on notions of individual authorship and objective knowledge. It is research that values, above all, the knowledge produced in and from the perspective of struggles themselves.

- The process of investigation is directly productive and political; producing new values, social relations, and subjectivities, creating new capacities and knowledges. It is the foundation for the formation of a new collective subject and the basis of the production of the common.

As Argentina enters a new period, no longer defined strictly by the neoliberalism of the 1990s nor the protests and experimentation of the 2001 moment, the insights learned from the inquiries of the past fifteen years cannot be forgotten. Since 2003, Argentina appears to have entered a period of political stability and economic recovery. The Kirchners came to power on the back of the struggles of 2001 and took up much of the movements’ discourse and demands, speaking of social change and economic justice and launching programs to (slightly) redistribute wealth. The government has also developed more complex ways of interacting with social movements, with less direct repression, instead opting for forms of co-optation and negotiation. The government attempts to use movements’ knowledge, hiring social scientists as well as activists in order to better understand the forms of life and subjectivities in marginalized areas, and to develop more sophisticated forms of governance. All of this takes place in a highly polarized political climate, where the only recognized positions are either with or against the government, and in which the majority of mass movements have chosen to support the government. In this context, the terms of struggle become confused: movements are increasingly institutionalized and the government takes on much of the work previously undertaken by movements; a complex web of relationships between social organizations and governments develops as each tries to take strategic advantage of the other. However, movements have lost much of their autonomous capacity to generate the new languages and forms of organization that were so prevalent in 2001.

The social programs, which do redistribute some amount of wealth, also serve to increase the government’s presence in formerly marginalized territories, expanding financing to cooperatives and other social movement activities, while attempting to control and contain those practices. With economic growth, new forms of extraction emerge to capture the fruits of social cooperation. 7 Precarious and informal work accounts for much of the growth in employment. The increased availability of credit (both microcredit loans financed by the government and NGOs and credit financed by banks) in low-income neighborhoods, along with the expansion of welfare programs, promotes consumption without a corresponding increase in formal employment. New subjectivities and desires emerge, linked more to consumption than to work, marked by individualist and competitive attitudes, as individual solutions come to be preferred over collective ones. These changes, along with the government’s attempts at co-optation, make organization increasingly difficult, and have led to growing fragmentation within and between movements. The MTDs find themselves in a difficult position: many people have either returned to employment or found other ways to meet their needs without relying on social movements, through government subsidies, credit, or from narco-trafficking organizations. 8

Once again, however, inquiry can play an important role in recomposing struggles. Profound investigation must be done into the new forms of capture, in order to develop a common struggle between the multiple sectors exploited and affected by all forms of extractive industries. In urban settings, this means investigating the expansion of debt and the financialization of more and more areas of life.

Inquiry must seek to understand to the subjectivities produced by these processes and develop the conditions for collective action. Investigation into the links between different extractive industries can help to build relationships between urban and rural struggles, especially the urban struggles of unemployed and precarious workers, and rural struggles against mega-mining and the destructive soy industry. Now investigation must move beyond the neighborhood to bring together different sectors in struggle. Inquiry needs to invent new languages and common discourses, moving beyond the polarization encouraged by the government and opposition political parties. Militant investigation, in this context, must go beyond sociological explorations of what is to propose new collective imaginaries and ways of being.

References

| ↑1 | The movements of the unemployed became known for their use of roadblocks, which often blocked traffic on major highways for days or weeks at a time. These roadblocks eventually won a number of concessions from municipal, provincial and national governments, including different forms of unemployment benefits, food aid, and in some cases jobs. Movements also won control over the distribution of these benefits: each organization is accorded a certain number of benefit plans which they then determine how to distribute among their members. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For more on the MTD La Matanza (in Spanish) see: Toty Flores, ed., De la culpa a la autogestión: Un recorrido del Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados de La Matanza (Buenos Aires: MTD Editora, 2005). |

| ↑3 | Colectivo Situaciones, and MTD de Solano, La Hipótesis 891: más allá de los piquetes (Buenos Aires: Ediciones de Mano en Mano, 2002). |

| ↑4 | For more on Colectivo Situaciones’ figure of the militant researcher in English see “On the Researcher-Militant,” available online at eicp.net. |

| ↑5 | Preface to Colectivo Situaciones, 19 & 20: Notes for a New Social Protagonism, trans. Nate Holdren and Sebastián Touza (New York: Minor Compositions, 2012), 6. |

| ↑6 | For more about these assemblies and processes of horizontal organizing see Marina Sitrin’s Everyday Revolutions: Horizontalism and Autonomy in Argentina, (New York: Zed Books, 2012), as well as the book by Colectivo Situaciones mentioned above. |

| ↑7 | In their article, “Is there a new state-form?” Veronica Gago, Sandro Mezzadra, Sebastian Scolnik and Diego Sztulwark argue that we must expand our concept of “extraction” to not only include processes of extraction of natural resources but also the ways in which financial capitalism captures the fruits of social cooperation, especially financial capitalism. |

| ↑8 | In a meeting in June, one activist from a poor neighborhood described how when her organization had attempted to hold an event for Children’s Day, giving out modest snacks and toys to children in the neighborhood as is customary, a local drug dealer upstaged their event by coming in on a truck and distributing much fancier brand name toys and events. Their organization, having no way to compete with the drug dealers, finds itself increasingly marginalized in the neighborhood. Because of the enormous disparity in resources between social movements and narco-trafficking organizations, people increasingly turn to local drug dealers or become involved in the drug trade to solve their problems. While not necessarily a new phenomenon, it seems to have recently become a much larger problem for the movements of the unemployed that now find themselves often directly clashing with local drug dealers. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine