From the earliest incursions of the Hudson’s Bay Company to the large-scale resource extractive developments of the present day, the history of Canada is fully commensurate with Indigenous struggle against capital accumulation and colonial dispossession—a heist, wrote Secwépemc leader Arthur Manuel, amounting to “in simple acreage, the biggest land theft in the history of mankind.”1 This sweeping reterritorialization was not accomplished at once, but by a range of violent and coercive means over centuries, culminating in the creation of the Canadian state; which at the end of the nineteenth century marked a significant advancement in the imperialist partition of the globe, opening almost ten million square kilometers of land to settlement and speculation.

This land, put simply, is Indigenous, whatever has transpired in the four hundred years since European settlement, and today’s cultures of resistance clearly demonstrate as much. From railway blockades in urban centers to efflorescent villages placed in the path of a pipeline, these methods traverse colonial infrastructure to convey the strength of many nations and locations to an economy from which Indigenous people are functionally excluded, and which in many ways demands their wholesale political destruction.

In this respect, the recurrent and ongoing blockades across the territories known as Canada typify a range of contemporary tactics focused on infrastructure and supply chain disruption. These developments would seem to confirm a number of prominent theories as to the changing terrain of class struggle, observing a shift in scenery from sites of production to far-flung logistical infrastructures and networks of circulation. In fact, these tactics have a long history in colonized North America—and as ever-greater integration and concentration of enterprise creates the conditions for new mass actions, collating geographically disparate struggles and paradoxically empowering regional interventions within global markets, these means acquire persuasive force, with the potential to enlist vast solidarities between anti-capitalist cohabitants on stolen land.

Without simplification, the history and present of these land-based and logistical actions offers a powerful playbook of decolonial internationalism, addressed to the tiered weaknesses of a global system. According to a 2021 report published by the Indigenous Environmental Network and Oil Change International, the last decade of Indigenous resistance in Canada and the United States has stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least twenty-five percent of annual emissions. This is impressive in itself; and moreover demonstrates that fossil capital cannot be meaningfully opposed without the full decolonization of the land it would exchange for private wealth. As such, the struggles analyzed below should not be regarded as discrete uprisings; but rather as occasions for the broadest possible coordination against a system of dispossession that grounds the capitalist project in North America.

All Eyes On Wet’suwet’en

Jurisdictionally assertive blockades and mechanical interventions in the circulation of goods surely date from the earliest incursions of colonial infrastructure. For the sake of urgency, however, a popular history of Indigenous counterlogistics might start nearer here in time—in the first months of 2020, when organized resistance to imperialist extraction on Indigenous land manifested in nearly every major city in Canada in the form of blockades and solidarity demonstrations. In a matter of days, these actions brought the colonial economy to a virtual halt, precipitating panic from investors and swift intervention by the state on their behalf.

This particular sequence started in Northern British Columbia with the Unist’ot’en village, “an Indigenous re-occupation of Wet’suwet’en land” purposed against the construction of a 670 kilometre-long pipeline by Coastal GasLink. In a statement posted to their website, Unist’ot’en calls for “solidarity actions from Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities who uphold Indigenous sovereignty and recognize the urgency of stopping resource extraction projects that threaten the lives of future generations.”

On December 31st 2019, the Supreme Court of British Columbia granted an injunction to Coastal Gaslink, to prevent interference in the construction of the $6.6-billion pipeline. On New Year’s Day, the Wet’suwet’en First Nation served Coastal GasLink with a notice of eviction from their unceded land. By February 6th, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) had moved in to enforce the injunction, essentially dispatched by the state as TC Energy Corporation’s own private security force, as protesters in Belleville, Ontario, four-thousand-odd kilometres away from Unist’ot’en, began stopping railway traffic along one of Via Rail’s busiest routes, precipitating a full cancellation of service. Within a day, Via Rail had cancelled travel between Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal altogether.

In the days to follow, blockades on Tyendinaga Mohawk and Kahnawà;ke Mohawk Territory (in Ontario and Quebec respectively so-called) began to interfere with supply chains, forcing manufacturers to subsidize cheap rail traffic with trucking at great expense, as demonstrations within Toronto and Montréal brought trains to a halt at the station. Near the town of Morris, Manitoba, train service and vehicle traffic were held up by a committed group of protesters, in spite of bitingly cold weather—one CBC story describes an official court injunction blowing away on the wind after an organizer refused to touch it—and within a week, CN Rail was forced to shut down its operations in Eastern Canada altogether as well.

While Prime Minister Justin Trudeau demanded the removal of the barricades, lashing out at Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, further blockades were organized across the country, and those standing were reinforced with concrete and dozens of further bodies. In British Columbia, members of the Secwepemc Nation blocked CP rail tracks repeatedly, forcing CEO Keith Creel to publicly demand that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau meet with Wet’suwet’en leadership. Trudeau declined, and after a 96-hour truce, the blockades resumed.

Amid temporary layoffs, the trade journal FreightWaves reported that the blockades “have caused ripples throughout the Commonwealth’s supply chain,” quoting the holistic wisdom of the Canadian Trucking Alliance: “when the railways suffer disruption in service, it impacts everyone in the economy including the trucking industry. When bridges and roads are blocked, trade stops and other modes and business sectors that depend on trucking services are negatively impacted. The Canadian economy overall depends on a reliable and fully functioning supply chain.” As business councils panicked, predicting a four-day recovery for every day of interrupted service, public opinion began to turn against Trudeau’s intransigence.

Within a week, relatively small groups of actors communicated with startling clarity that the basis for Canada’s wealth both requires, and lacks, Indigenous consent. Land defenders had issued a call to #ShutDownCanada, and with production delays throughout China already slowing shipments and lowering container volumes, blockaders quickly and clearly demonstrated how effectively this could be accomplished.

Capillary Colonization

This susceptibility is as old as the country itself, inherent in the methods by which a vast and uneven geography was sutured by a nascent Canadian state. As geographer Shiri Pasternak explains, authorities have always been wary of the susceptibility of railway infrastructure to interference from the nations whose territory they transgress. As a 2007 RCMP briefing to CSIS on operational responses to Indigenous protest warns, “the recent CN strike [referring to the Tyendinaga Mohawk rail blockades in April 2007] represents the extent in which a national railway blockade could affect the economy of Canada.“2 This briefing was born out in 2012 and 2013 during the Idle No More movement, during which more than one hundred blockades of rail and road traffic were coordinated across the county.

Last winter’s events further corroborate this state directive, as do any number of blockades ongoing at this very moment. As Kwakwaka’wakw artist and historian Gord Hill observes, “the reason these railways are so vulnerable to this type of action is because they were punched through reserves,” relaying the agency of geographically remote communities to cities and colonial shareholders. Pasternak sketches a paradigmatic impasse, where the placement of First Nations, even after relegation to isolated locales, constantly runs up against the capitalist necessity of expansion into new frontiers:

In addition to these massive expanses of treaty areas and unceded traditional territories, Indigenous lands were historically fragmented into isolated and remote reserves by successive colonial administrations. There are over 2,600 Indian reserves across Canada today … This forced settlement resulted in a unique spatial phenomenon that unwittingly placed Indian reserves on the frontier of vital national and regional boundaries: frontiers, for example, for natural resource extraction, suburban development, military training grounds, oceans and in-land waterways, state borders, and energy generation.3

In this sense, the means of the Canadian state have developed but little diverged from those employed before Confederation. In addition to a neocolonial politics of official reconciliation and assimilation, a prototypically colonial process of accumulation continues to structure relations between Indigenous nations and the Canadian state in the present. This continuity both necessitates today’s blockades and explains their efficacy, as an expression of political sovereignty and a means of solidarity, depending on differential relations to land.

These blockades are important displays of settler support for Indigenous land defense, and of Indigenous nations with one another. More broadly, they also typify the twenty-first century proliferation of interventions within the supply chain, exerting tremendous economic and political pressure within and around transportation hubs where people are commonly perceived to have little agency. As scholar Charmaine Chua describes, logistical processes create crucial sites of political intervention in core capitalist countries, where new accumulation strategies emphasize movement over location, and circulation over production:

Since the 1970s, the revolution in logistics and supply chain management has shifted capital’s focus from its sites of production to its sites of circulation: no longer able to generate substantial profit from the mechanized and labor-saving technologies of factory manufacturing, firms began to experiment with increasing the speed and efficiency through which commodities could circulate across the globe.4

This “capillary” regime, within which fewer people are meaningfully employed in the service of ever more profitable enterprises, renders the traditional labor strike difficult to envisage for many: “for how can one conscientiously withdraw one’s labor in protest if one is excluded from the sphere of production, and awash instead in a sea of planetary capital flows?”5 Chua’s work responds to one popular account of financialization, in which people are increasingly powerless to intervene in capital accumulation as producers, recommending the literal capacity of people on the ground to halt circulation at “chokepoints” along the supply chain instead. And while this thesis should be qualified with reference with an uptake in militant labor organization the worldover, Chua’s examples are timely, including the Block the Boat for Gaza actions, during which dock workers refused to offload goods transported by ZIM, Israel’s largest cargo company; and the massive protests at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline, which is itself an important instalment in the sequence of twenty-first century Indigenous land defense. Without reducing the variety of means by which workers leverage their collective power, there can be little doubt that the practice of blockading is of great tactical importance today.

The level of modal integration that typifies containerization follows a particular development of monopoly capitalism, where a handful of global firms direct the movement of goods from independent producers. Chua describes the logistical turn as a new strategy of accumulation, linking the deindustrialization of imperial core countries to the rapidly developing productive forces of the periphery, and addressing crises of overaccumulation by growing the access of goods to markets. This is certainly one facet of an immense development, in which one can plainly see the necessity of colonial expansion for capitalism.

The culmination of monopoly capitalism in military advancement is well established from its earliest theoreticians. But in the settlement of North America, one finds striking pre-configurations of this dynamic, beginning long before the periodization of Lenin and his contemporaries. In this sense, centuries of Indigenous resistance even anticipate the chokepoint protests of the advanced capitalist present, where many Indigenous people who never underwent a formal process of proletarianization have necessarily organized against an occupying state from outside as well as within the working class. To understand these logistical struggles as such, however, it’s worthwhile to sketch the global circumstances under which the colonization of these territories transpired.

War By Other Means

Geographer Owen Toews identifies the colonization of what is now called Canada as an instance of the spatial fix—the movement of capital and labor to a new region or frontier to evade crises of overaccumulation—in which respect it anticipates the contemporary impetus to containerization. Canadian expansionism westward, Toews explains, came about in response to global and continental crisis:

The material momentum for the expansionist movement came from two sources: first, a worldwide overaccumulation of capital and subsequent search for new markets, and second, the related, growing spectre of a complete US takeover of Turtle Island, which would erase Canadian capitalists’ special access to markets and force them to compete directly with US firms.6

With the Royal Charter of King Charles, written in 1670, the newly formed Hudson’s Bay Company became absolute Lords and Proprietors of more than a third of present-day Canada. For the next two centuries, the HBC attempted to exert a monopoly over the trade in furs and provisions across large swathes of North America. During these years, the HBC effectively comprised an autocratic government in Rupert’s Land, advancing settlement under the authority of a company-state. From the 1668 voyage of the Nonsuch through Hudson Straits and into Hudson Bay, the HBC managed a profitable maritime conduit between Britain and its North American colonies. In addition to changing the course of world trade with its fleet of wooden ships, the HBC orchestrated a great deal of inland travel, through water routes and across variegated terrain. But as Gord Hill describes, the transition from feudalism to capitalism in Europe brought new forms of domination to the colonies, including “the introduction of bank loans directed primarily at developing infrastructures for the export of raw and manufactured materials: roads, railways, and ports, particularly in the mining and agricultural industries.”7

In 1863, the HBC shifted emphasis from the fur trade to acquisition of land, with the purchase of controlling shares by the newly established International Financial Society, representing the interest of a group of London banks in the territories of Western Canada. As historian John C. Galbraith notes, this included powerful investors in the Grand Trunk Railway, operating throughout eastern Canada and the United States.8 With this influx of capital, railway mileage in Canada increased more than 1500 percent in the 1850s alone. In an 1863 prospectus, the HBC promised to “inaugurate a new policy of colonization” in the so-called Southern District, encouraging land sales without much forethought as to the administration of the region.

English investment and restructuring were decisive factors in the push for colonization. As Galbraith explains, the rush to invest in land stemmed from a contemporary mania for speculation in England: “It was the expectation of immediate land sales which motivated shareholders to invest £2,000,000 in an enterprise which, apart from the value of its land, was valued at under £1,250,000.”9 Of course the land-based assets of the HBC were highly speculative, insofar as colonization would require extensive infrastructural development and an increased governing presence, neither of which the company could furnish themselves. Thus began an elaborate negotiation with Canada, then a British province, over the terms of acquisition and administration, as anxious shareholders came to realize that Canadian cooperation would be required to secure the territory in which they had already invested, at court and from American expansionism.

The corporate drive behind this conquest was not for novelty’s sake, but part of a larger trend towards financialization in a tumultuous moment for global capitalism. By the 1860s in England, a period of relative stagnation in productive industries had resulted in increased investment of surplus capital in financial markets, such as those overseen by banks like Overend Gurney, trading in discounted bills of exchange. But this shortfall in domestic production was intimately connected to developments abroad. In his characterization of the Panic of 1866, Karl Marx describes the investment of superfluous capital in money markets as a response to the interruption of cotton imports, where this capital would otherwise have been directed, paving the way for a predominantly financial crisis.10

Lancashire’s textile industry relied upon the import of raw cotton from the slave-owning Southern States of America, much as the system of slavery depended upon short-term credit from English banks. After a period of enthusiastic overproduction in the late 1850s, threatening profits and eventually employment in the factories of North West England, the English textile industry recovered; that is, until its main supplier of raw materials, the Southern States of America, declared a war of secession in 1861. During the American Civil War, President Lincoln set up blockades of a dozen southern ports, preventing the transportation of goods in and out, such that the confederacy’s wartime logistics relied increasingly upon “blockade runners,” smaller vessels carrying less and less cargo in order to evade naval monitoring. (Marx references the American Civil War as a global correlate of the English cotton famine, naming it “the Greatest Example of an Interruption in the Production Process through Scarcity and Dearness of Raw Material.”11)

The Confederacy presumed international, and particularly British, dependency on cotton for their sovereignty; and British industry depended pitifully upon African enslavement in North America, though Britain had officially abolished slavery in its own colonies in 1833. This codependency was an important means of staving off, or lessening, roughly decennial crisis. But as the financial bubble of the mid-1860s offset shortages caused by a de facto cotton embargo, the expansion of British colonies elsewhere in North America, such as the North-West, transpired as a spatial fix to incipient market collapse, permitting the IFS to endure the financial crisis of 1866. Thus the restructuring of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and its westward expansion, concatenates the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the colonization of North America with the consolidation of the English working class.

In a sense, HBC was a logistics empire from its founding, benefitting enormously from sole access to a sea route by which English ships carrying goods could arrive at Hudson Bay and return to England with furs inside of half a year. This greatly accelerated business cycle not only confirmed a competitive advantage over the rival North West Company, but allowed for English merchant capitalism to penetrate a vast territory of many national and commercial interests. On the continent, however, river blockades of provisions were instrumental in fur trade wars of political consequence. In the aftermath of the historic victory at Frog Plain, an event of foundational importance for a nascent Métis nation, the “Bois-Brûlés,” in the employ of the North West Company, blocked HBC passage on the waterways and disturbed supply lines to persuasive effect.12

According to Alberto Toscano, supply chain infrastructure constitutes only so many sites of political and economic intervention, and this was no different in the colonial economy of North America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Following labor historian Sergio Bologna, Toscano explains how capitalism requires the expansion “in particular of ‘supply chain management‘, conceived of in terms of the speed, flexibility, control, capillary character and global coverage of the stocking, transport and circulation of services and commodities.”13

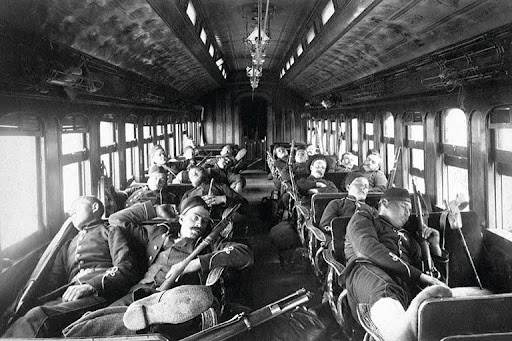

Logistics originates as a practical concern of militaries, charged with the transportation of goods and personnel over great distances under duress. Yet one observes a technological interchange between programs of commerce and conquest, whether by land, sea and air, as means are differently applied in and out of wartime. During the First World War, in a pertinent example, HBC served as the chief purchasing and shipping agent of the French government, offering a fleet of more than 250 ships. Merchant vessels such as the S.S. Nascopie were quickly repurposed to bring munitions and supplies to the European front. This reverses a more typical pattern, where military technologies predict commercial applications—many of the practices of international freight transport that markets take for granted today were advanced during the transnational wars of the twentieth century. Politics is war by other means, it is said; and one might say the same of international trade on a large scale, which relies upon the means of war.

Insofar as the history of Canada’s settlement by British and French interests is also the history of several competitive firms, commerce appears to coincide with military power, to the degree that these can be formally separated in the first place. The logistics of trans-Atlantic oceanic travel and the domestic fur trade define the early colonial era, and the violence of occupation increases with the expediency of its means. For this reason, Canada is a particularly strong case study of the inseparability of state power and transportation infrastructure.

Breaking the Plains

Construction on the Canadian Pacific Railway, extending from Montreal to Vancouver, began in 1881 and concluded a scant four years later amid triumphalist fanfare. The CPR was a crucial requirement of Canadian national identity, both symbolically and practically, and before completion would allow Prime Minister John A. MacDonald to move troops west and quickly suppress the Northwest Resistance of 1885. The success of this route in quelling the uprising is acknowledged as a major reason for the government’s decision to extend further credit to the CPR—William Cornelius Van Horne, as president of the CPR, quipped that the company should build a monument to Métis leader Louis Riel for his role in finishing the railway.

MacDonald’s government had pledged to connect the coasts by rail in the 1870s, and this project was championed by capitalists in both directions—by British Columbia as a condition of their entering confederation, and by eastern Canadian manufacturing firms seeking new markets. As the Indian Act of 1876 attempted to executively strip Indigenous people of any national rights with the express goal of cultural annihilation, the railroad functioned not only to expedite settlement, but as an engine of genocide itself. Historian James Daschuk writes that in 1882, Prime Minister John A. MacDonald “announced to Parliament that all Indians in the territory of Assiniboia would be removed by force, if necessary, from the land south of the proposed railway. Within a year, 5,000 people were expelled from the Cypress Hills. In doing so, the Canadian government set about the ethnic cleansing of southwestern Saskatchewan of its Indigenous population.”14

Further west, the proposed route of the CPR transgressed the territory of the Siksika nation in Alberta, whom the government had failed to consult. In 1883, Siksika militants tore up railway tracks as they were being laid down, and put up significant resistance to the construction as it ran through their reserve. Eventually Father Arthur Lacombe, a missionary priest working on behalf of the government, would convince Chief Crowfoot, or Isapo-muxika, that the railway was unstoppable, and to accept the inevitable in exchange for a lifetime pass on the railroad.15

Such developments are typical of a transitional moment in the imperialist epoch. In his theorization of ‘continental imperialism,’ Manu Karuka describes North American settler colonialism after Lenin’s characterization of monopoly capitalism, mapping developments in the United States onto Lenin’s timeline:

Lenin periodized the evolution of capitalism into imperialism in three phases. The first, from 1860–70, the period of the building of the transcontinental railroad, he described as the height of free competition. Following the financial crisis of 1873, which was triggered by Lakota resistance to incursions on their homelands by the Northern Pacific Railroad, Lenin argued that we begin to see the emergence of cartels. In the third stage, which proceeded through the boom conditions at the end of the nineteenth century, culminating in the economic crisis at the turn of the century, “cartels become one of the foundations of the whole of economic life. Capitalism has been transformed into imperialism.”16

Karuka is certainly correct to characterize the United States in this fashion, and his description applies to Canada too, which is likewise “not a national entity, but an imperial one, an international cartel that supplies a framework for coordination among major monopolist trusts.”17 Canada’s gradual, and then accelerated, transition from an extractive or trade colony, in which sojourning profiteers supplied raw materials to Europe, to fully fledged settler colonialism corresponds to an inexorable tendency of imperialism to partition of land, such that “in the future only redivision is possible, i.e., territories can only pass from one ‘owner’ to another.”18

Lenin observes that “for Great Britain, the period of the enormous expansion of colonial conquests was that between 1860 and 1880”—a span corresponding to the restructuring of the HBC after the interests of the IFS, and encompassing the creation of Canada in 1867 by an Act of British parliament.19 As Arthur Manuel quips, this was “more a corporate reorganization, a hurried consolidation of debts, than the birth of a nation,” in keeping with the close relationship of state and corporation that typifies imperialism.20 In this phase of capitalist development, Karuka explains, the “state splits itself into usurer and debtor functions, sustaining the circulation of finance capital across national and imperial boundaries.”

In the United States, Karuka looks to the financing of the Union Pacific railroad by companies like Crédit Mobilier, created by Union Pacific executives, which infamously overcharged for construction and then routed the profits to government officials as bribes. In Canada, a lucrative contract for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway was promised to shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan in exchange for a sizable donation to Prime Minister John A. MacDonald’s re-election campaign. Notably, both scandals relating to the financing of national railroads came to a head in 1872, as these territorializing projects proceeded apace at the start of the cartel movement.

In Lenin’s account, the imperialist epoch is infrastructurally prepared; such that he confidently cites the total length of railway in a given territory as an index of the rate of growth of finance capital. By the time of its completion in 1885, owing in no small part to the hyper-exploitation of over 17,000 Chinese laborers, the Canadian Pacific Railway had added more than 20,000 kilometres of track to the continent, and enveloped more than 25 million acres along its route, prime real estate for westbound settlers.21 In respect of this illegitimate acquisition, the CPR became a barony throughout the west, profiting enormously from land sales and settlement as well as the transportation of commodities. This is the very process by which land and resources held in common by their original inhabitants were forcefully privatized, by expansion and decree.

“A Vast Imperial, Industrial Workshop”

As railways tore through Indigenous land, cities blossomed along its route. Close to the geographical center of North America, at the longitudinal center of Canada, one finds the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, located on Treaty 1 territory. Winnipeg sits at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, two powerful tributaries which form part of an enormous continental network of waterways, and this meeting place was an important center of trade for centuries preceding colonization. As the placement of this city on the site of the first permanent European settlements in the west had directly to do with the importance of waterways to trade, its economic ascendance would depend entirely upon the railway.

For a period of time, Winnipeg’s economic fortune was secured by its status as a central node of a vast logistical network, spanning the continent it centers. In his narration of the CPR, historian Pierre Berton describes a period of rapid population growth and frantic real estate speculation, coinciding with the construction of the railway and concerning the projected placement of its stations. As Winnipeg’s population doubled, Berton writes, “its assessment tripled,” and the city of sixteen thousand would soon boast three-hundred real estate dealers.22

As history would have it, the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 would effectively end this boom. In an optimistic article for Maclean’s Magazine written in 1912, columnist Roy Fry writes of “the supremacy of Canada’s natural strategic position,” predicting British Columbia’s central place in a new era of capitalist accumulation: “it follows that incredible riches are destined to flow into, and be developed in, those countries occupying the Western coast of North America which have good harbors, docking facilities, defences, a merchant marine and an adequate navy.” This propitious report bodes well for British Columbia as “a vast Imperial industrial workshop,” and Canada’s role in the world economy more broadly.

The year before Fry’s enthusiastic article, however, William E. Curtis of the Chicago Record-Herald wrote that Winnipeg was “a gateway through which all the commerce of the East and the West, and the North and the South must flow. No city, in America at least, has such absolute and complete command over the wholesale trade of so vast an area.” However, as shipping routes for grain to Europe were directed westward, Vancouver grew as Winnipeg declined. Today, the Canadian Pacific yard bisects the city, covering more than 200 acres and contributing to the economic and racial segregation of the North End from the downtown; but few would describe Winnipeg’s railyards in such grandiloquent terms.

Nonetheless, the 1960s saw the opening of Symington Yards, one of the largest rail yards in the world today. Symington handles 3,000 cars per day, and stores more than twice that amount. A 2019 CN strike brought traffic at the largest switchyard in the country to a standstill, exerting tremendous economic pressure where agricultural producers, retailers, and more recently, petroleum companies depend upon this method of transportation. According to Barry Prentice, a professor in supply chain management, railways “carry about half the total tonnage of freight moved in Canada and are critical to the export of most Canadian commodities,” including connections to container ports and overseas links in port cities like Vancouver. For this reason, Prentice warned in February 2020 that losses from the solidarity blockades could reach billions of dollars without a solution. Exacerbated by seasonal reductions in speed and environmental factors, these demonstrations were perfectly timed, striking not at the heart but at the vessels of empire.

Dispossession and Oppression

Throughout her work, Chua theorizes a strategy of chokepoint protest to concentrate economic agency without the mediation of workplace enrollment or organized labor. This readily describes a range of contemporary actions by land defenders, as protests in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en Nation join a long history of Indigenous blockades and land-based interventions that can only be described as logistical, going back to the early years of colonial infrastructure, where Indigenous people have been systematically and structurally excluded from the sphere of production from the inception of the settler colonial project.

Scholar Peter Kulchyski suggests that Indigenous people may have contributed the labor and resources fundamental to capitalism’s success in North America, “but whatever their position may have been they were clearly not wage workers forced to sell their labour power on an open market. They retained access to their own subsistence (the ‘means of production’ in Marx’s terms) and retained through the whole period a strong sense of distinctiveness, grounded materially in a hunting economy.”

Kulchyski argues that Indigenous people were not dispossessed of their means of subsistence in identical fashion to European enclosure, but maintained a minimal degree of access to land, however mediated by an occupying state. Similarly, Dene scholar Glen Coulthard demonstrates that attempts to sever Indigenous people from their land were seldom purposed at assimilation into a minimally enfranchised working class per se, but were often explicitly genocidal in intent. In Coulthard’s words, “it appears that the history and experience of dispossession, not proletarianization, has been the dominant background structure shaping the character of the historical relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian state.”23

In this, Coulthard complicates and rejects the standard order of operations according to which primitive accumulation or dispossession of land takes place prior to the creation of a disenfranchised working class. For these purposes, primitive accumulation names the sum of extractive processes that transpire alongside capitalism and are concurrent with its inner logic, such that it cannot be assigned the status of a proletarian primal scene. As Coulthard writes, “settler-colonialism is territorially acquisitive in perpetuity.”24 Likewise, when Marx describes “so-called primitive accumulation” as political economy’s doctrine of original sin, he doesn’t appear to propose that such a transgression ever transpired once and for all; rather, this metaphor suggests that the distant antecedence of this process is a narrative effect of privatization in the present.

“Colonialism has three components,” writes Secwépemc leader Arthur Manuel: “dispossession, dependence and oppression.” The first component, dispossession, agrees with a fairly orthodox Marxist account of proletarianization, where people are forced from a traditional, land-based means of subsistence, either to sell their labor as a commodity or descend into the sphere of pauperism. But Manuel’s other criteria, dependence and national oppression, are unique to the situation of the colonized, and have even prevented Indigenous access to market as nominally free labor. These three facets of colonization may be considered processually, where oppression is a means of dispossession in the present; though Manuel’s first-person account of enclosure is organized chronologically:

It began with dispossession: our lands were stolen out from underneath us. The next step was to ensure that we are made entirely dependent on the interlopers so they can control every aspect of our lives and ensure we are not able to rise up to seize back our lands. To do this, they strip us of our ability to provide for ourselves … We were suddenly corralled onto reserves under the authority of an Indian agent and given a few gardening tools for sustenance. In some areas, where the land was particularly fertile and the Indigenous peoples managed to generate small surpluses and tried to sell them, local white farmers complained about the competition and laws were passed forbidding us from selling our produce. It is important to note that our poverty is not a by-product of domination but an essential element of it.25

As Manuel explains, dependency upon welfare and relief programs functions to keep Indigenous people off of the land, as an object of investment and a source of wealth in itself. By this logic, Indigenous labor is often worth less than Indigenous acquiescence, hence one observes a special degree of isolation that actively excludes those dispossessed of land from easily entering into the labor force. As Manuel writes, “we were to be kept penned in on our 0.2% reserves until we were starved out and drifted onto skid row in the city and gradually disappeared as peoples.”26 Métis scholar Howard Adams locates Indigenous people as a “rural subproletariat,” owing to the recomposition of the working class as part of settler colonial expansion. In Adams’ chronology, “when mercantilism changed to industrialism, Indian workers became irrelevant,” and were subsequently corralled into reserves. “This quasi-fascist practice was not because Indians were savages who were incapable of progressive development,” Adams continues, “but because railroad barons needed Native territory for their railway industry.”27 As Coulthard summarizes:

It is now generally acknowledged among historians and political economists that following the waves of colonial settlement that marked the transition between mercantile and industrial capitalism (roughly spanning the years 1860-1914, but with significant variation between geographical regions), Native labor became increasingly (although by no means entirely) superfluous to the political and economic development of the Canadian state …28

This is an important characteristic of settler colonialism, where Indigenous labor becomes less important to Canadian capitalism as emigration intensifies, corresponding to the European deployment of capital and labor surpluses abroad. Coulthard describes “increased European settlement combined with an imported, hyper-exploited non-European workforce,” such as the many Chinese laborers who built the Canadian Pacific Railway.29 “This is not to suggest, however, that the long-term goal of indoctrinating the Indigenous population to the principles of private property, possessive individualism, and menial wage work did not constitute an important focus of Canadian Indian policy,” Coulthard explains, but that Indigenous people were first and foremost confronted in their relation to land itself.30

A Place of Law

None of this denies the preponderance of Indigenous laborers in certain areas and trades, nor the representation of Indigenous people within a larger working class. Kahnawà;ke Mohawk anthropologist Audra Simpson describes the “ironworking Mohawk, specifically from Kahnawà;ke … tied up with capital and the material reproduction of the community as well as postindustrial skylines.”31 Many laborers from Kahnawà;ke commute to large and dangerous construction sites throughout the Northeastern United States, crossing a border drawn across their territory by two colonial states. Itemizing the infrastructure that comprises this political nexus, much of which was built with Indigenous labor (and Indigenous resources, on Indigenous land) Simpson observes the affirmative refusal in two directions of the Haudenosaunee worker, who carry their own Confederacy passports.32 This practice of “nested sovereignty,” in Simpson’s words, belies the settled, or decided, temporality of the colony, which presumes Indigenous law and presence alike to have been effectively replaced. It’s apparent from this complicated example that working class enrollment hasn’t functionally severed Indigenous workers from their traditional lands, where these relationships are differently mediated in each case.

Simpson’s theorization of nested sovereignty is clarifying, where many accounts of the efficacy of blockades tend towards a kind of insurrectionary economism. In each of the cases described above, it’s important to observe how Indigenous blockades, in their specificity, are ineluctably political. They are not simply ‘bargaining by blockading,’ as some theorists would have it. As Shiri Pasternak explains, “the blockade is a place where two systems of law are forced to meet.” Blockades thus trace “a difficult relationship between two legal systems that come face to face on highways, logging roads, rail lines, and other sites of infrastructure and development throughout the country.”33 According to Nishnaabeg writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, these thresholds are an infrastructure of diplomacy, enacting a refusal of Canadian authority at the same time as they affirm cultural and political resurgence, as “a collective embodiment of Indigenous legal practices.”34

Pasternak describes the struggle of the Algonquins of Barriere Lake against the federal government: “The community of Barriere Lake blockaded often throughout the 1990s to stop the clear-cut logging of their lands. They sought to pressure Canada and Quebec to honor their agreements set out in the three-row wampum exchanged in 1760 and renewed in 1991 through a resource co-management agreement.”35 More recently, Pasternak looks to Freda Huson of the Unist’ot’en camp, and her eviction of prospectors sent into Wet’suwet’en territory by Coastal GasLink. Insofar as Huson asserts traditional jurisdiction, a standard language that has developed around blockades as sites of extra-legal “occupation” is clearly insufficient, if not flatly insensitive, to the international relationships staged by these sites. Where the blockade operates as a legal threshold, Canadian police and developers are the outside occupiers, contravening the law of another’s land.

While these sovereignties are distinct, Indigenous struggles against colonial incursion are intimately connected by the force of their common adversary. In Northwestern Ontario, Grassy Narrows First Nation maintains one of the longest standing blockades in Canadian history, having controlled access roads used by clear cutters on their land since December 2002. In a high-profile case from 2006, the Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation successfully fought off the company Platinex from developing a mine on Big Trout Lake. KI not only barricaded access roads, for which six land defenders were briefly imprisoned, but completed a 2100-kilometre trek from Kenora to Toronto after Platinex filed a $10 billion lawsuit against KI for protecting their traditional territory.

In Caledonia, Ontario, on Haudenosaunee (Six Nations) territory, a group of Indigenous land defenders and their supporters established “the 1492 Land Back Lane blockade” in July 2020 to oppose a plan by Foxgate Developments to build more than two hundred homes and townhouses at Caledonia, functionally encircling Six Nations. As Kanienkehaka lawyer Beverley Jacobs explains, the Haudenosaunee have never given up title to the land and resources, for which Canada owes them today.

In October 2020, Foxgate Developments, together with the county, successfully petitioned a Superior Court Justice for an injunction against any gathering or barricade on this site. But as Jacobs notes, the ease with which corporate lawyers can get an injunction from colonial courts has nothing to do with justice, or Haudenosaunee law. After the first injunction on August 5th, the Ontario Provincial Police moved in on the camp, arresting nine people. Land defenders started tire fires on Highway 6, forcing the OPP to close the roads, and reoccupied the site by night. However, the police continued to arrest land defenders at a further remove from the camp, and on October 22nd escalated events irreparably with tasers and rubber bullets. As a consequence, 1492 Land Back Lane dug a trench across the highway, blocking the entrance to the McKenzie Meadows development, and excavated CN Rail tracks nearby. Construction ground to a halt, as Foxgate attempted to claim millions of dollars in damages for delays. Finally, after a year-long standoff, Foxgate Developments announced on July 1st, 2021, that they were abandoning the McKenzie Road build, citing resistance from Haudenosanee land defenders and the persistence of their 25-acre blockade.

On Secwepemc territory, near Blue River and Moonbeam Creek in British Columbia, a group of land defenders calling themselves the Tiny House Warriors are opposing the Trans Mountain pipeline by constructing ten tiny houses along its 518 kilometre path, “to assert Secwepemc Law and jurisdiction and block access to this pipeline.” Enduring violent attacks by settlers and trumped-up arrests, the Tiny House Warriors clearly demonstrate the constructive and lawful dimension of blockading, where any impediment to developers is simultaneously constructed with the goal of re-establishing village sites on their unceded Territories: “Each tiny house will provide housing to Secwepemc families facing a housing crisis due to deliberate colonial impoverishment. Each home will eventually be installed with off-the-grid solar power.”

Work on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion has stalled in the last year after multiple accidents, but there is tremendous political will to complete the pipeline, which the federal government purchased from Kinder Morgan for $4.4 billion in 2018 amid mounting legal challenges. In light of President Joe Biden’s executive order cancelling permits for the Keystone XL pipeline, which would have spanned from Alberta’s oil sands to Nebraska, pressure from Alberta’s oil industry to finish the remaining construction on the Trans Mountain project is greater than ever; which only threatens to escalate state violence and civilian vigilantism against Indigenous blockaders. In the early morning of July 23rd 2021, Trans Mountain employees and private security forces replaced fences around the Tiny House Warriors village near Blue River with their own concrete barricade, preventing Secwepemc land defenders from accessing the road as well as water and food sources.

Where over 50% of the proposed pipeline route crosses Secwempemc territory, it’s not difficult to understand the tremendous resistance of the capitalist state to this assertion of sovereignty, which threatens an estimated $73 billion in revenue for producers, and $46 billion for the government, over the next 20 years. “Canada is not going to listen to us until we start disrupting their economy,” affirms Tiny House Warrior Kanahus Manuel, “which is based on the theft of Indigenous lands.”

A Common Interest

On this basis, one practice of blockading—of geographically isolated assertions of land-based sovereignty by remote nations—connects directly with another, the chokepoint protests of organizers in cities and distribution centers. This conveys the agency of Indigenous land defenders directly to urban locales, and drafts new possibilities for settler and working-class solidarity with anti-colonial struggle—a solidarity that again traverses the infrastructure it would obstruct, in a demonstration appropriate to the scale of global capitalism. As these tactics interfere in capital both fixed and fluid, many assumptions about the political location of an unsorted working class and its improper representation come into play.

As CN Rail bemoaned the layoff of 450 operational staff at the height of last February’s stoppages, all of whom were eventually recalled, Teamsters Canada took a reactionary stance, advocating for “ordinary, working-class Canadians who have nothing to do with the Coastal GasLink pipeline.” Of course the sacrifice of workers has nothing to do with land defenders but with the ruling class—as Dakota/Lakota Sioux writer and lawyer Ruth H. Hopkins points out, CN had planned layoffs of roughly 1,600 personnel as early as December 2019, following an eight-day strike that similarly brought traffic to a halt.

But this is only a small part of the picture. Gitxsan organizer Kolin Sutherland-Wilson notes that large numbers of relevant unions in affected territories refused to cross lines during the #ShutdownCanada campaign; and many of Canada’s largest unions were quick to offer support to the Wet’suwet’en and Unist’ot’en. While Canada’s agriculture industry and its grain-handling system depends entirely upon rail traffic, the National Farmers Union issued a statement in solidarity with land defenders at the height of the confrontations.

In addition to the possibility of deepening solidarity from organized labor, logistical clusters across the continent have left capital exposed to disruption from masses of precarious workers, engaged in acts of civil disobedience in cities from coast to coast. This vulnerability only increases with the speed and reliability of supply chains, as a unique consequence of capitalism’s transgression of lived spaces, eventually enabling communities and organizers to reassert distance itself as impediment to profit. As supply chain expert Prentice notes, “transportation is a service. It can’t be stockpiled. Some blocks of time are more valuable than others. Meeting container ship schedules is particularly important because of the high value of the cargo and the costs of delaying a ship. Any time lost when the trains are not moving is lost forever.” It is this lost and profitable time that legislators in western Canada are attempting to make up in advance.

On November 2nd, Manitoba’s Progressive Conservative government introduced Bill 57, the Protection of Critical Infrastructure Act. This was one of 19 separate bills introduced without text, expediting the passage of unseen and undebated legislation by a Conservative majority. Fully revealed in March 2021, Bill 57 proposed to create a special criminal offense for obstruction of railways, highways, and anything that “makes a significant contribution to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of Manitobans” by its presence. As critics of the bill have pointed out, this definition of infrastructure is so broad as to potentially include any site of gathering whatsoever—and while the text includes a motley schedule of examples, from animal feedlots to banking services, it also makes provisions for private owners to apply for a court order, establishing a “critical infrastructure protection zone.” The penalties for interference in such a zone include heavy, steeply graduated fines compounded by the day, and potential imprisonment. As Shiri Pasternak and Tia Dafnos explain, “in today’s logistics economy, the state is redefining its ‘resilience’ in terms of its relative success in the protection and expansion of critical infrastructures,” reconfiguring Indigenous jurisdiction as a legal risk.36

Manitoba’s Protection of Critical Infrastructure Act, momentarily thwarted by a popular movement on the ground, closely follows Alberta’s controversial Bill 1, passed by the United Conservative Party in May 2020. After the events of February, during which an estimated $11 million of goods were held up at chokepoints around Edmonton alone, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney and his cabinet responded with racist vituperation, decrying the antics of “ecoterrorists” and advancing claims that protestors were receiving foreign funding to disturb the Canadian economy. These are tellingly errant characterizations of Indigenous-led protests, and one should immediately observe the fantastic proximity of Indigenous resistance to foreign infiltration in the right-wing imaginary.

Kenney’s cabinet frequently attempt to link any opposition to pipeline construction in Canada, and Alberta specifically, to foreign interests; connecting interference in Canadian oil production to the fortunes of “authoritarian” states, especially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, led by the “caudillo” Nicolás Maduro. Kenney’s invective is colourful; but his characterization of these state competitors and their leaders as “oleo-gopolists” only invites a serious question as to whether or not Kenney is one such himself, depending on Alberta’s oilfields to secure his political fortunes and to buoy a crashed economy, while cracking down on Indigenous resistance and popular dissent.37 As the Conservative Party drums up pan-partisan support for a Cold Trade War against China, federal leader Erin O’Toole pushes for Canada to “kick-start the relationship” with India—“the world’s largest democracy” by capitalist standards. So it should come as no surprise that Reliance Industries, a foremost antagonist in the “postcolonial autumn” of Indian farmers, signed a deal promising to purchase 2 million barrels of Canadian crude oil per month, just as the United States reescalated sanctions against Venezuela.

This alignment is entirely in keeping with the imperialist consolidation of capitals, as natural gas producers in Canada and the United States, including nine Albertan CEOs, have started to push for the establishment of a North American oil cartel. This is unlikely to transpire as such, but where joint ventures like the LNG Canada Project, including the Coastal GasLink Pipeline, are concerned, this is a merely legal distinction. This “comedy of oil” spans borders, so it should come as no surprise that these Canadian anti-protest bills closely resemble legislation drafted by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a right-wing corporate lobby whose motto is “Limited Government, Free Markets, Federalism.” ALEC is responsible for the writing of Oklahoma House Bill 1123, which was introduced in 2017 to suppress protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, and likewise “creates new law relating to the crime of trespassing on property containing a critical infrastructure facility without permission.” This resemblance connects struggles as well, where these pipelines remain a joint interest of U.S. and Canadian investors, and jurisdiction is the least concern of extractive capital.

This proposed legislation was intended to chill protest, but only strengthened the solidarity of unions and the workers they represent with Indigenous land defenders. In June, the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees (AUPE) filed a claim against the government, emphasizing that the expansive definition of essential infrastructure put forth by Bill 1 poses a major threat to union members, who could face charges for leafleting or picketing in front of their own places of work. On Treaty 1 territory, Unifor and the National Farmers Union (NFU) strongly denounced Bill 57, and Grand Chief Jerry Daniels of the Southern Chiefs Organization, representing 34 Anishinaabe and Dakota communities, vowed to oppose the bill in every aspect.

As Canada intensifies its criminalization of Indigenous resistance, it is more urgent than ever for labor to clarify its purpose and position alongside these many connected struggles. As one can see, there are no insulated agendas in politics, where the further immiseration of Indian farmers by monopoly capital is intricately but plainly linked to the ongoing dispossession and national oppression of Indigenous peoples by the Canadian state; and an implicated working class endures the cruelty and caprice of layoffs and mergers as a major oil boom draws to a close. Alongside Bill 1, Alberta’s United Conservative Party initiated a series of sweeping attacks on labor, driving down wages for the oil and gas workers whose alleged interests are played against Indigenous self-determination as a matter of course.

What are We Doing Here?

In February 2021, a year after the coordinated actions in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en Nation, a group of Inuit hunters moved to blockade the Mary River iron ore mine on North Baffin Island, Nunavut. As protesters camped in the middle of a line of snowmobiles, calling attention to the ecological devastating effects of a proposed mine expansion by the Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation, protests and blockades appeared across the northern territory. Blockading the region’s airstrip, Nuluujaat Land Guardians effectively prevented hundreds of staff from southern provinces from leaving the region. Some of these sojourning managers denounced the action, but in a surprising development, a “sizable minority” of these workers published an eloquent letter endorsing the blockaders’ right to self-determination, and the definitive say over their territory and their way of life. The document is worth quoting from at some length, as an exemplary statement of class-conscious solidarity with Indigenous struggle:

This is an open letter to the protesters at Baffinland Mary River mine site from a group of employees at the mine.

Our managers have cautioned us that speaking out about this publicly will likely result in termination, and so this letter must remain anonymous.

We are writing to express our full support for the efforts, means and goals of your protest. We do not pretend to represent the views of the majority of Baffinland’s workers, but we do represent a sizeable minority.

We recognize the Inuit as the rightful custodians of this land, and as the people who should make the decisions about how it is used.

Your protest has generated a lot of conversation among the workers here. Many of us are disappointed that our flights to return home were postponed, but some also consider it a small thing compared to the hundreds of years of colonization and cultural erasure that Indigenous people have experienced — and continue to experience — at the hands of the Canadian government and the private sector.

This country has seen the consequences of entitlement and greed that have led to the destruction of the land for profit, and we are glad you are fighting for autonomy over your land.

You’ve said that it is not the workers you are upset with, but the Baffinland executives, and we would like to say that our support is also not with our superiors in the company, but with you.

On many occasions we’ve looked around at the massive piles of iron ore surrounded by miles of rusted snow, the colossal diesel tanks and the clouds of exhaust fumes that hang above the camp and thought, “What the hell are we doing here?”

We firmly believe that the company should listen to your demands and give you what you want, though even that will likely not be enough. With the horrible history that has taken place in this country, and the ways in which your voices were silenced in the process, what could be enough?

Despite the injunction that is now forcing you to vacate the airstrip, we hope that you go on to succeed in your goal to prevent Baffinland’s phase two project to double their output and build a railway.

This expansion would obviously affect the wildlife and ecosystem in the surrounding area, which would be another step in erasing your means of sustaining yourselves through hunting. We see the importance of protecting the way of life that you’ve practised for thousands of years. A message to the public just learning about this: workers at Baffinland are safe, and have not been in danger at any stage of this situation.

The protesters said from the start that they would let flights leave in cases of emergency. We have enough food to last us a very long time, and while we are disappointed with our cancelled flights, as stated earlier: it is nothing compared to the importance of listening to these peoples’ voices as they fight to protect the land and their culture.

Clear-headed and without condition, this communication alludes to the necessity of a multinational movement against capitalism, and for Indigenous sovereignty, within Canada’s settler colonial context; and the capitalist class appears eager to disarticulate any such popular alliance in advance of its activation. As Baffinland threatened to scale back its operation under cover of a market downturn, pressure from Inuit communities and environmental groups continued to mount. While hearings are yet to resume, equipment stockpiled in anticipation of phase two expansion has already been removed. Put simply, blockades work, escalating risk to distant investors; and when workers steel themselves against the long-term extortion of employers, drastic changes in course are possible—though seldom reported with the interest afforded disruption.

It isn’t difficult to imagine why this might be so. In February 2020, at the height of nationwide blockading in support of the Wet’suwet’en, Val Litwin, president and CEO of the British Columbia Chamber of Commerce, offered a parodic intimation of this deepening solidarity, accusing non-Indigenous protesters of “appropriating an Indigenous issue for their own self-serving purposes … In so doing, they are hurting the very people they purport to represent — the thousands of working men and women (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) who rely on development to put food on the table …”

Litwin’s dismissal of settler solidarity with Indigenous land defense, appropriating a discourse of appropriation, conceals its motivation behind a veil of concern for working people. This is a novel variation on a time-honoured rhetoric of division; superficially acknowledging the legitimacy of an ‘Indigenous issue’ of which working class settlers have no part. This attempt to localize and segregate resistance is perhaps analogous to the larger situation of Indigenous nations in Canada; an isolation belied by today’s blockades and logistical interventions.

Further, any recommendation of burgeoning solidarity cannot be predicated on a romanticized split between a settler working class and an Indigenous subproletariat, where proletarianization proceeds unevenly as part of an assimilationist strategy. The tar sands, for example, are Canada’s largest employer of Indigenous people, followed by mining companies—a fact which Cree environmental activist Clayton Thomas-Müller compares to a hostage situation.38 The Canadian Energy Centre, an Alberta-based corporation commonly known as the “Energy War Room,” routinely uses the comparatively high proportion of Indigenous people employed in the energy sector to argue for the expansion of oil sands and extractive development, citing higher median incomes and lower dependency on government transfers, as though individual purchasing power could equate to sovereignty. As capitalists attempt to dissuade support for Indigenous self-determination by convincing labor that its interests are otherwise aligned, they must increasingly address themselves to Indigenous workers, whose terms of employment in a colonial economy are meant to supersede any stake in national liberation. Accordingly, a properly political labor movement, emphasizing the contradictory interests of labor and capital, offers a powerful alternative to this attempted bribe.

Coincidentally, as blockades sprung up across the country in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en, hundreds of striking workers at the Federated Co-operatives Limited Refinery in Regina, Saskatchewan constructed a blockade around the facility, effectively shutting down production as pension negotiations fell apart. A second blockade appeared at a cardlock terminal in Carseland, where fuel arrives by train for distribution. As police attacked picketers at multiple locations, the state itself established a correspondence between discrete struggles against the profiteers of extractive industry, from within and without an enfranchised workforce.

These workers are surely among those whose interest Litwin evokes, though their stake in the industry clearly differs in kind from the industry’s stake in sovereign and unceded land. Thus nêhiyaw writer Emily Riddle asks directly: “what if unions began leveraging their multi-million-dollar budgets, massive memberships, paid organizers, and political power to support Indigenous land defense and repatriation? Unions must realize that police are arresting workers and land defenders for the same reason—to keep the oil flowing to help big corporations make a profit, at the expense of working-class livelihoods and Indigenous sovereignty.”

Spatializing Solidarity

The repression of blockaders by the state appears a necessary part of the economy, where the sheer technical scale of monopoly capitalism produces a structural susceptibility to interference, directly linking geographically isolated sites of development to cities and financial centres. These actions address the contemporaneity of extractive and settler colonialisms, of primitive accumulation and financial capitalism; amplifying the agency of small groups of people in remote locations within an enormous logistical framework. In this respect, these interventions are powerfully equipped to stage resistance to a settler state, where demographic change subordinates an Indigenous population.

Where 99.8% of so-called Canada is claimed either by the Crown or private interests, these assertions of Indigenous power are amplified by way of the land of which Indigenous nations are dispossessed—reasserted as unbreachable distance and as practical impediment, as solidarity and as jurisdiction. As people rally to the land, myriad relationships abstracted by capital as simple measures of time and space assume agentive salience.39 This sublime depth of space appears to the capitalist as a loss of profit—but the Indigenous claim to territory slights exchange in its living solicitude; as a complexity to rival any supply chain.

This spatialization of international solidarity actually includes the land that it defends as a participant factor. Moreover, where Indigenous people are typically subjugated by spatial rather than temporal alienation—of land rather than of labor, as per Coulthard—these interventions, linking extraction to circulation, assert a powerful co-theory. Space is simply distance from a capitalist standpoint, and where backlogs and missed deadlines exert a domino effect (“any time lost when the trains are not moving is lost forever”), protesters in urban transportation hubs may consciously withdraw industrial efficiency alongside consent to a social, rather than a union, contract. As importantly, these actions attest to cultures of Indigenous resurgence that span and surpass the colonial duality of city and reserve, urban and rural space.

The decolonial movements and tactics described above trace the history of capital accumulation in North America, from early merchant competition to settler expansionism and monopoly possession of colonial land. But these movements draw strength from the grounded relationships of millennia preceding. As Métis and Cree writer Mike Gouldhawke describes, “these already structured and long-held relations are what allow us to quickly respond to situations as they arise, with a strategic eye toward the future, toward securing a land and social base for generations to come.” This resurgence is assured, and its political accompaniment in the present provides us with unquestionably powerful examples of multinational resistance to the capitalist state—both as a map of its susceptibilities, and an embodiment of the many systems of life and collaboration beyond its concern.

References

| ↑1 | Peter McFarlane and Nicole Schabus, Whose Land Is It Anyway? A Manual for Decolonization (Vancouver: Federation of Post-Secondary Educators of BC, 2017), 20. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Shiri Pasternak, ‘Occupy(ed) Canada: The Political Economy of Indigenous Dispossession’ in The Kino-nda-niimi Collective, The Winter We Danced: Voices from the Past, the Future, and the Idle No More Movement (Winnipeg: ARP Books, 2014), 42. |

| ↑3 | Pasternak, 43. |

| ↑4 | Charmaine Chua, Logistics, Capitalist Circulation, Chokepoints. September 9, 2014 https://thedisorderofthings.com/2014/09/09/logistics-capitalist-circulation-chokepoints/. |

| ↑5 | Ibid. |

| ↑6 | Owen Toews, Stolen City: Racial Capitalism and the Making of Winnipeg (Winnipeg: ARP Books, 2018), 36. |

| ↑7 | Gord Hill, 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance (Oakland: PM Press, 2009), 33. |

| ↑8 | John C. Galbraith, ‘The Hudson’s Bay Land Controversy, 1863-1869’ in The Mississippi Valley Historical Review

Vol. 36, No. 3 (Dec., 1949), pp. 457-478. |

| ↑9 | Galbraith, 462. |

| ↑10 | Karl Marx, Capital Volume I (New York and London: Penguin, 1990), 822. |

| ↑11 | Karl Marx, Capital Volume III (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1977), 128. |

| ↑12 | Jean Teillet, The North-West Is Our Mother: The Story of Louis Riel’s People, The Métis Nation (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2019), 74. |

| ↑13 | Alberto Toscano, ‘Logistics and Opposition,’ in Mute Vol. 3 No. 2, 9 August 2011. https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/logistics-and-opposition. |

| ↑14 | James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013), 123. |

| ↑15 | Around the same time and to the south, Lakota led coordinated attacks on freight and construction trains during the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. |

| ↑16 | Manu Karuka, Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019), 176. |

| ↑17 | Karuka, 177. |

| ↑18 | V.I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism: A Popular Outline (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1973), 90. |

| ↑19 | Lenin, 91. |

| ↑20 | Arthur Manuel and Grant Chief Ronald Derrickson, The Reconciliation Manifesto: Recovering The Land, Rebuilding the Economy (Toronto: James Lorimer and Company, 2017), 63. |

| ↑21 | Notably, the subsurface rights acquired in this exchange would change hands over the course of several mergers in the century to follow, eventually comprising the basis of wealth for Encana Corporation, one of Canada’s largest oil companies. |

| ↑22 | Pierre Berton, The Last Spike: The Great Railway 1881-1885 (Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2001), 53. |

| ↑23 | Glen Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 13. |

| ↑24 | Coulthard, 152. |

| ↑25 | A Manual for Decolonization, 19. |

| ↑26 | Ibid, 20. |

| ↑27 | Howard Adams, A Tortured People: The Politics of Colonization (Penticton: Theytus Books, 1995), 198. |

| ↑28 | Coulthard, 12. |

| ↑29 | Ibid. |

| ↑30 | Ibid |

| ↑31 | Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014). |

| ↑32 | In 1990, when the town of Oka unilaterally approved plans to extend a golf course onto Mohawk land at Kanehsatà:ke, kin from Kahnawà;ke blocked the Honoré Mercier Bridge across the St. Lawrence River, connecting the reserve to the island of Montreal, stopping traffic for more than a month. At Simpson’s suggestion, this should be construed not as a simple impediment to the circulation of goods, but as an assertion of territorial and national sovereignty, closely related to the eviction of non-Mohawk residents from Kahnawà;ke in the 1980s. |

| ↑33 | A Manual for Decolonization, 33. |

| ↑34 | Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, A Short History of the Blockade (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2021), 11. |

| ↑35 | Ibid. |

| ↑36 | Shiri Pasternak and Tia Dafnos, ‘How does a settler state secure the circuitry of capital?’ in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2018, Vol. 36 (4), 739–757. |

| ↑37 | As early as fall 2019, international observers had criticized the Conservative Party’s “Fight Back Strategy,” which convened a “war room” to protect corporate interests, for infringing Alberta’s human rights obligations. |

| ↑38 | Clayton Thomas-Müller, Life in the City of Dirty Water (Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2021), 117. |

| ↑39 | “A fundamental difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous concepts of internationalism is that for Indigenous peoples, internationalism takes place within grounded normativity … My nation is not just composed of Nishhnaabeg. It is a series of relationships with plant nations, animal nations, insects, bodies of water, air, soil, and spiritual beings in addition to the Indigenous nations with whom we share parts of our territory. Indigenous internationalism isn’t just between peoples. It is created and maintained with all the living beings in Kina Gchi Nishnaabeg-ogamig.” Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 56. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine