Critique communiste: Robert Linhart, you led the Althusserian tendency within the Union of Communist Students (UEC), which went on to establish the Union of Communist Youth (Marxist-Leninist) (UJCML).1 In May 1968 we often clashed with the UJCML under your leadership. After your organization’s crisis and that of the Maoist current more generally, you didn’t follow the same path as a good number of former Maoist leaders recast today within the intellectual establishment of the academy and the “Nouvelle Philosophie.” When anti-Leninism was at the peak of fashion, you published a book that was incongruous with this trend: Lenin, the Peasants, Taylor.2 You’ve just published The Assembly Line with Minuit, a personal account we all read and appreciated at Critique Communiste.3 With hindsight, what is your assessment of your militant past? How do you understand your militancy now?

Robert Linhart: The critical moment in the collapse of so-called “Maoist” organizations can be situated around 1972. In any case, throughout their decade-long existence, from their birth inside UEC onwards, our successive organizations always existed in a state of crisis. Independently of all the external upheavals and contradictory pressures emanating from wider society, they contained an element of internal crisis: our attempt to break with a mode of action conceived solely as a form of primitive accumulation of a capital of militants. We seized upon the Chinese Cultural Revolution for forms of organization that were more contradictory and unstable than those previously bequeathed by the tradition of the communist movement. As Marxist-Leninists, we sought radical innovation in terms of the theory and practice of organization. We sought to establish a much more dialectical type of organization, one capable of calling itself into question, of destroying itself, of shifting itself from one social base to another, of recomposing itself. Against the orientation of our own “Marxist-Leninist” and then “Maoist” organizations, we launched “movements” that by their repetition and magnitude contributed to surprising growth and breakthroughs, and also provoked perpetual crises. The final crisis intervened between 1971 and 1973.

Certainly, other organizations born since have claimed Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought for themselves. But it seems to me that the overall situation in which they conduct their efforts and the relationship that they can have with the Chinese Revolution today are very different than those existing for previous waves. I will only speak, therefore, of the generation of Marxist-Leninist militants in which I participated, myself.

At the time of that final crisis, the problem we confronted, insofar as we were professional revolutionaries – passing from a single strike to the organization of a group of factory militants, from a movement among the armed forces to a prison uprising, from organizing a demonstration to writing magazine articles – can be easily formulated: how to reinsert ourselves back into society? No doubt, like me, you know the tremendous consequences of individuals operating enclosed within a politically confined world, where we only know people who share our own views, and where all information is passed through an incredibly rigid grid. A collective interpretation is almost always immediately arrived at and the world, deprived of its mysteries and of its complex hues, ends up reduced to a collection of stereotypes. We see schizophrenic behavior begin to develop. A dream-world and a dream-France, only distantly related to the real world and the real France, are constructed. The mechanics of this breakdown are easy to unpack. For a few hundred people between 1965 and 1972, France was only perceived through strikes, demonstrations, incidents that broke out at different points in society or in the state apparatus. These people never engaged in ordinary activity in a business, an office, an ordinary community, as we do every day (including the uneventful days!). The cross-section of society that we knew had no value for a representation of the whole, since we always chose places where things were happening. Elsewhere things were quite spectacularly not happening; an essential part of reality escaped from view, and a completely distorted view of reality resulted.

This always posed a problem and it took a particularly acute form in the end. When I worked for the press of the GP (Gauche prolétarienne) (J’Accuse and then la Cause du peuple-J’Accuse), two lines were vigorously opposed to each other. One sought to establish a relationship with reality that was not entirely disconnected – nor deceptive: if only 500 people attended a demonstration one would say that there were only 500 people; if a strike went badly, one would explain why it went badly. The other line could be called voluntarism or idealism but it also encompassed those forms that were most skeptical towards the will to power and careerism of petit-bourgeois intellectuals. This line consisted in saying: we represent the proletariat; if our comrades from the rank-and-file demand that we say that there were 10,000 people then we must say so, etc. Conflict of this sort occurred regularly and pushed us into a vicious cycle: voluntarist pressures cut us off from those we called “democrats” or people we could have formed links with, and this greatly reduced our ability to appreciate reality.

There’s one point I’d like to insist upon. I describe here what I knew directly. But, in my opinion, it’s a very general phenomenon. While certain so-called “Maoist” organizations took this capacity for schizophrenia to an extreme, it seems to me to be a property of all far-left organizations. No doubt, for other comrades it’s not actually exhibited in such a pathological form, but it is evident from reading their newspapers, or from listening to their interpretations of events, that the whole of social reality finds itself sifted through a very weak framework, with very few variations and where one can almost always predict in advance what will be said of one thing or another. By the way, this is what always makes reading the far left’s newspapers an absolute source of sadness. Moreover, far-left militants often see themselves as somehow sticking to reality by accepting the institutional form through which our society produces “news” (items reported or even constructed by the major newspapers and other journalistic outlets and indeed “political life” itself, as is seen these days with “anniversaries” and other such idiocies…). In bowing down before this artificial superstructure, they more often than not neglect to explore fields of reality that almost never appear on the news (since the news is a rigorously limited representation that society generates of itself). At the extreme, there is a curious conjunction of schizophrenia and conformism, which I believe would make a good subject for analysis. This mechanism, which we came to know in pathological form, continues to exist in a mode that could be described as more routine, more normal…

These problems about how to perceive the world and how to reinsert ourselves back into society have confronted us for a long time, including the whole period of our activity as professional revolutionaries. One can always evade the issue, until the moment comes when the organization collapses and everyone finds themselves at sea. Whether or not we want to, each of us then has to re-enter “ordinary” relations with society. Or, not quite always, to tell the truth. It’s a question of occupational and social activity as well as of one’s mentality. And, certain well-placed individuals find a loophole at a price – affordable enough to them apparently – of becoming spectacular turncoats. Fundamentally, the leading rhetoricians and other windbags of the nouvelle philosophie continue to follow the same old formula. They turn out any old sophistry from scraps of reality, which are then sorted through a rudimentary framework before being incorporated into an elaborate fantasy with delirious themes all of its own. This is quite artificial (since they are far from mad…). But only a handful of people who are full of hot air make a lot of noise. The overwhelming majority of militants have been scattered in numerous different directions.

From 1972 onwards, the strategies of people who had participated in our movement came to be abruptly individualized yet again. Everyone tried to find a way out, and there were lots of different routes. Some showed a panic-stricken fear of ordinary life, of the reality of finding stable work again, of having occupational responsibilities. They found for themselves a thousand and one reasons to continue the lifestyle of the militant free from the constraints of common social life, yet still tied to the cultural or intellectual order – all to avoid plunging into the fate faced by the majority of 53 million French people.

Others invested the abilities they had been able to acquire during their militant period in various sectors: campaigning, advertising, research, journalism, psychoanalysis, etc.

Others, for their part, have tried, despite brutal changes in conditions, to maintain continuity in their activity. To both find an occupation, a normal relationship with society, re-establishing a dialogue with people who think and live differently from themselves, while still continuing to fight in this altered universe for the same things: the birth of political forces linked to the working class; resistance to capitalist and imperialist oppression; the struggle against exploitation. Some became lawyers and continued to defend workers by specializing in employment law. Others were linked to the unions. Others even stayed on the shop floor and were said, therefore, to have become “naturalized” workers.

We have covered a very difficult period and I think it has been useful to let the dust settle. The ambitious ones who had bet, 10 or 15 years ago, on rapid revolutionary success to secure their place in the sun did not resist the backlash of the 1970s. Their renunciations multiplied as they threw themselves into the arms of the bourgeoisie. Good riddance. The others, the vast majority, I’m sure, will one day struggle once again, only with stronger convictions and vaster experience.

For my part, I took up the role of teacher and economist. I dedicated all of my work, inquiry, writing, research, teaching, to the question of production. That is to say, essentially, to everything that concerns the operation of industrial and agricultural production, to how goods are produced today: steel, petrol, automobiles, radio sets, knitwear, corn, Liège lace, hormone-laced veal, plates, etc., etc.

Underlying these choices, there is a simple idea. It seems to me that we have a very superficial and hazy understanding of the working class and production. More than a century after Capital, there remains a largely unexplored world to be discovered.

And often we hold on to ideas, definitions, and descriptions from that moment when Marxism was born and first encountered the working-class movement. Well, the world has changed since Marx’s epoch. And if it is true, as Marx said, that the relations of production are the heart of society, of the system of exploitation, it seems to me that it is difficult to form an opinion no matter the subject (ideology, the state, superstructure, international relations, the general tendencies of societies…) without researching relatively concrete (and up to date) knowledge of relations of production – of the real way men produce objects.

Principally, I do this with a method I have experimented with for quite a long time (since 1964), that of the inquiry in various forms. I think that it is indispensable to maintain and develop a direct relationship with the real world of production. Otherwise, no reading or documentary effort can suffice to yield more than barely adequate knowledge. My most recent works are: an inquiry on technology transfer in Algeria in 1974; participation in agrarian reforms in the south of Portugal in 1975 (where I worked for a time with teams from the Agrarian Reform Regional Centres which helped to expropriate the large landowners, and to form collective bargaining units managed by agricultural workers); and the establishment, along with French trade union organizations, of inquiries and courses intended for workers on the organization of labor (in the auto, petrochemical, and cement industries in particular). In addition, I teach at the University of Vincennes and, in intermittent fashion, for the personnel of INSEE.4 I hope that this overview of my current professional and political activity more-or-less addresses your question.

CC: With regards to questions of the production process, very important changes have occurred in the past ten years that are often ignored, under-appreciated, misunderstood. Could you outline these?

RL: I’d first like to comment on a point you raise that also seems important to me too: the difficulty of acquiring knowledge of these changes and, more generally, the difficult of acquiring knowledge of the production process. This might seem altogether strange, but if we suppose someone wanted to provide an audience interested in these issues (students for example) with an account of the way in which we produce, say, textiles in France (the scale and of units of production, the production process itself, how labor is broken-down and standardized, the division of labor between different enterprises and within each of them, the description of machinery and motion….), it couldn’t be done. I’ve had this problem myself and I’ve resolved it only imperfectly. It’s practically impossible to find works on large industries that are simple, descriptive, and (I insist on this point) global in scope; on the complete process by which we move from raw material to a finished product.

Evidently, an enormous literature exists on the “sociology of labor,” but it always lacks an overall analysis of the process of production (no doubt because we presume that other disciplines cover this: economics, technology… But economists don’t take into account the concrete reality of the production process while studies of technology are at once too specialized and too compartmentalized to provide an overview).

What happens is that researchers overstate the significance of a certain number of specific job roles and situations at work on the basis of which we get descriptions, analyses, and arguments to the detriment of an overarching perspective and analysis of the labor force which contributes to a particular industry. Take the steel industry as an example of the ways changes have intervened in labor. Look at the rolling mill. We once fused metal bars by hand, with the help of pincers. This has since been automated.

It is all computerized today. There have been three generations of rolling mill operators, etc. Fine, today a rolling mill operator generally works 3 x 8 shifts from a control room, running an enormous facility through labor that is in large part intellectual – or at least not based upon physical effort. Instead, we’re right to insist on mental exertion, on wear and tear, and the disruption that accompanies shift work, etc. But to suggest that we have here the overall transformation of manual labor and that “antiquated” forms of production based upon the hyper-exploitation of physical effort and the direct control of movements tend to be effaced within the most modern industries, is to become detached from the reality of a labor process that remains much more complex and unequal than we often imagine. You will find a number of studies, for example, on the shiftwork of rolling mill operators or the shiftwork of petrochemical workers, or various other types of manual labor. But most case studies of this sort have a ridiculous aspect if we do not take the prior precaution of verifying how the recomposition of the production process has produced other types of workers often relegated to unskilled labor, other satellites industries, other points at which labor-power is concentrated (construction sites, industrial zones, industrial port zones, enormous shipyards, etc.).

We cannot eschew a point of view of the whole if we want to perceive the real changes happening to manual labor. Often, the physical tasks from which one person has been relieved have surreptitiously been reallocated to someone else, but this is semi-obscured by subcontracting agreements or management contracts. The enormous steel mill rolls do not dismantle themselves; the giant distillation tanks and columns do not clean themselves through the power of the Holy Spirit. The push-button factory that we hear so much idle chat about is nothing but trompe d’œil, the emerging tip of an iceberg. To truly understand the production process, one must delve into the whole of enterprise, all the people, all the groups of workers that participate in the production of a product or a set of products. We then discover an increasingly complex system of production along with all its ramifications: subcontracting both nationally and internationally, service contractors, temporary work, the interpenetration of firms, capital investment, production plants. We discover that it is increasingly difficult to track a product and to delimit the frontiers of a determinate production process. This is the first obstacle, and it is a substantial one. Before even saying: “Alright, we’re going to study the transformations that have occurred in petrochemicals, in the steel industry, or the production of aluminum”, one must seek to delimit what that represents as a concrete field of inquiry. To do so is to assume that, to know how steel is produced, it is sufficient to have the list of job descriptions at Sacilor.5 But this is completely false. There are stacks of other companies that participate in steel production: AVS (“À votre service”), SOMAFER, SKF, SPIE Batignolles, both large and small firms, specialist companies, operations companies, companies not classified as steel producers but as mechanics, construction, metalwork, electronics, distribution, recruitment, engineering, etc. Dozens and dozens of enterprises.

Here lies the first difficulty. It rests with the increasingly complex character of the process of production. Moreover, to be rigorous one would need to take into account the entirety of operations taking place internationally: production, services, engineering. For example, if one wants to examine an oil empire, evidently, one must incorporate a vast distribution system.

Recent events revealed a fragment of this reality where the transportation of oil by fleets sailing under flags of convenience is concerned. Shipowners charter cargo for large multinationals on ships used to the point that, at times, one could describe them as “floating slums” where a sub-proletarian crew recruited in the Third World under draconian contracts work in shocking conditions. You have veritable slave traders who subcontract shipping for Shell, as was made evident in the Amoco Cadiz disaster.6 It’s as true for Exxon, BP, for the fleets of ore carriers and for all manner of distribution networks. Given there had been a disaster, the newspapers discussed it a bit in the case of Shell. When there isn’t a disaster, nobody speaks of it. This means that, in general, people retain a mythological view: Shell is a large company, with a workforce that is an aristocracy of labor, etc. But the miserable sailors from Hong Kong, from Formosa, or from Singapore, who are carted about upon immense floating tombs with cargos of 200,000 or 500,000 tonnes of oil contribute just as much to Shell’s profits as the migrant workers that work in very tough conditions in refineries and elsewhere and which go unmentioned in the public tours of refineries or in accounts of work in oil industry brochures. And moreover, such a system is equally thoroughly developed for distribution, for cleaning, maintenance, the production of byproducts, etc.

There’s a second challenge. Even supposing that we’ve succeeded in approximately delimiting the object of study adequately, the world of production is not easily penetrated. Those that hold the first-hand knowledge are people with vested interests. On the one hand, the capitalists, on the other hand, the workers. In addition, all those who assist in production: industrial engineers, management, etc.; all of these people have a direct relation to production. The management at Sacilor know approximately how steel is produced. They can define company strategy. They know which roles will be reorganized, the functions which will be outsourced from the company and placed with subcontractors, the evolution of personnel and procurement policies and the rhythm of production. They know where they’re going and they know where they’ve been. They confront Usinor, etc.7 But, as you know, this is an extremely impenetrable world. The CNPF,8 employers, the steel industry, iron masters9 all have a reputation for discretion. For instance, there’s global surveillance of steel unions through a system of police files, intelligence-sharing, and a close analysis of the evolving mindset of the workforce. Of course, all of this is done in secret.

Information circulates between employers and the upper echelons of management. The bosses travel, visit, and study what is being done in the United States, in Japan, or in the Scandinavian countries. They keep themselves up to date. They get into the details of the challenges or bottlenecks at Volvo or the successes at Toyota. But as a coherent system, all of this remains the exclusive domain of the employers. Occasionally, we catch a glimpse of how this is applied at some point or other and we learn by chance of an innovation that is the fruit of such exchanges of experience. For example, at Radiotechnique de Rambouillet (part of Philips), a boss returned from Japan inspired by the local practice of giving badges to those workers deemed to be of “good quality”; those who commit errors below a given percentage limit and who achieve certain rates. The company in question produces car radios, with a predominantly female workforce, and with tasks strictly Taylorized. The workers have to attach components to circuits made in Taiwan or elsewhere and, in principle, the minimum [sic] threshold for errors is three in ten thousand operations. This demands an extraordinary visual effort. Now, workers who do not exceed three errors thus receive a badge and a small bonus. It’s a means of posing workers against one another. Naturally, one wouldn’t find a published study explaining that this company decided to apply Japanese methods. A whole body of analysis and information circulates among employers that workers perceive only through its application, and which people on the outside cannot become aware of unless they come into contact with those working in the company. Capitalists thus study the process of production and exchange knowledge among themselves, but this rarely leaves their milieu and even then only in the form of its practical applications.

And there is a further large category of people who have knowledge of the process of production, these are the workers. Their knowledge is naturally much more profound. (If 500 Philips engineers were assigned to production work at Radiotechnique this would yield nothing, certainly not radios!) But at the same time, it is far more fragmented. Workers are confined to one role without knowledge of what goes on elsewhere. Almost everywhere, employers can say to this or that group of workers that their case is “an exception”. It is difficult for them, the workers, to recompose the entirety of the process of production. Moreover, one hardly has the time for this when one works eight or ten hours per day. There is massive potential for knowledge that is practically unexplored, undeveloped. Of course, there are the trade unions. But when trade unionists get together they have so many problems to resolve that in general, they don’t find the time to address this one. On this subject, one must insist on the fact that, since 1968, employers increasingly suck trade unionists into negotiating mechanisms, in commissions, in consultations, training, etc., that eat up most of their time, such as facility time or days on call. This erosion of trade unionists’ time means that they often struggle to describe concretely what happens within corporations, not out of bad faith but due to this deliberate policy of upward absorption carried out by employers, which is a subtle policy for wearing them down. From the trade union side, then, there’s no systematic development of the fields of knowledge of the process of production. Inequalities in terms of trade union representation constitute further obstacles to forming a complete overview.

If we accept that people who are inside the process of production abstain for one reason or another from systematically reporting on production to those on the outside, or only communicate in snippets, where can this information come from? I know very well that all of this doesn’t prevent academics and those referred to as researchers from producing a mountain of texts on labor, production, and industry. But we can easily note that there is a cumulative process that nourishes itself on professional necessities. Each writes primarily about what others have written and books essentially devour and transform books, not experiences and direct knowledge. Hence there is a gigantic disproportion between the volume of works printed and the modest quantity of concrete information that circulates.

In brief, if we want to understand something, I think there’s nothing to do but go see it oneself and to patiently collect the most direct knowledge possible. Go see the sites of production, speak with workers and businesspeople, engineers, work where possible together with workers, participate directly in production. This patient work of identifying reality as concretely as possible is what I call “making inquiries.”

I would like to make a final remark on the urgency of this method. It seems to me that we’re entering a period where the concealment of the realities of production by the bourgeoisie’s propaganda and “information” systems has characteristics that are much more subtle and, hence, more efficient and more dangerous than in the past. Employers have been in the process, for a number of years now, of moving towards a policy of “openness” and “branding.”

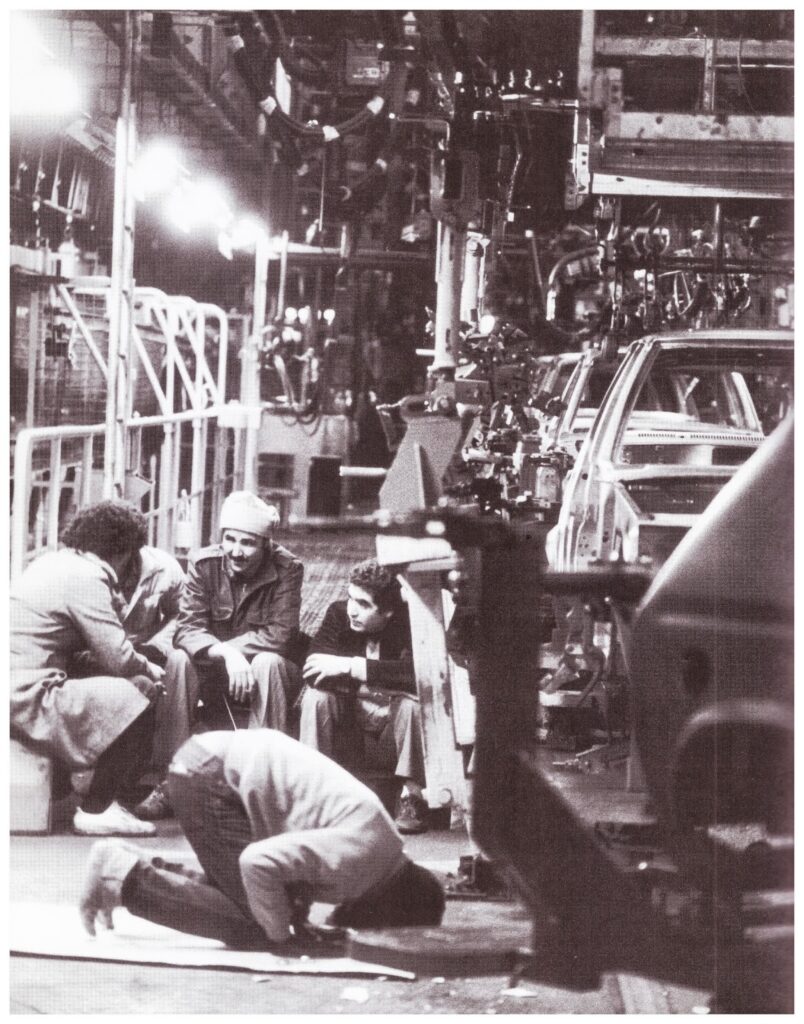

Fifteeen or so years ago, factories amounted to a closed world and one had to seek out testimonies. Today, they feign opening up to some extent. Employers progressively arrived at the idea that it was more advantageous to have delegations or groups come and show them select things rather than imposing a wall of silence.

One therefore sees the development of a systematic policy of factory visits, more or less acknowledged publicity films (at times distributed under the guise of journalism, on television for example), exhibitions and various means of imagery that, for instance, today feed campaigns like that of Stoléru’s “revalorization of manual labor.”10 It’s a deliberate strategy that, far from putting an end to the internal absolutism or totalitarianism of the enterprise, only perfects it. In France the Citroën archipelago is a totalitarian police universe, whose outward representation is systematically framed and oriented by grossly deceptive propaganda. The CNPF has published a brochure on factory visits for the bosses themselves. It suggests how to organize visits, how to set them up, how to welcome visitors, and how to produce the desired effect the “right image.” It’s all very precise, down to the rhythm of the tour and the best type of itinerary. One amusing detail: it insists that the route for arriving at the factory be perfectly marked. Otherwise, we learn, visitors risk “erring” into streets such as “Maurice Thorez” or “Henri Barbusse” in inhospitable neighborhoods and which would certainly aggravate them…

We’re thus perhaps heading towards more clever methods of obscuring the labor process which will permit bosses to “show” the interior of the factory. Not all of them though. For instance, today one cannot visit Renault-Billancourt but one can visit Renault-Flins. It’s true that the tour is rushed and that it’s impossible to get a sense of the cadence of an assembly line when one traverses the shop floor in two minutes. In addition, we don’t get to visit the shopfloors of large-scale presses, foundries, paint shops… But most of all, for a lot of industries, to show the large central enterprise is to offer a truncated view of the tangle of labors bearing on the final product. We’d visit a refinery control room but we’d never be brought for a tour of the small subcontractors’ plants, the managers, the slavers that furnish thousands of people to the enterprise. Just recently a grave accident occurred at the Rhône-Poulenc factory at Pont-de-Claix: the four hundred victims were immigrants, temporary workers. We have there the means by which the statistical rates of large industrial accidents are artificially reduced: the people doing manual labor within a facility are decreasingly employed directly by the enterprise and instead are subcontracted; the accidents affecting them will be strewn across diverse enterprises in transport, in construction, in metalwork, metallurgy.

It’s very important to have all this in mind to understand that no one today can accurately claim: “I will explain to you the labor process and production in steelmaking, automotive, textiles…” It’s really difficult. One is obliged to grope. One often follows circuitous paths.

I’m not saying this to dodge the question, but to try to show the limits and lacunae that accompany any answer. Given these reservations, it seems to me that on the whole we’re witnessing, along with a lot of inequalities and complex forms, a tendency born in the continual process industries…

CC: Which is to say?

RL: To produce an object on an industrial scale in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, men needed to get hold of raw materials, work it directly, passing discontinuously through the different stages of the division of labor. With the development of chemistry, organic chemistry, and the petrochemical and steel industries, we find ourselves faced with units of production that no longer correspond with this schema, which arose out of craft manufacturing and the ancient trades. These new types of units of production consist of the achievements of the laboratory expanded to the scale of an actual industrial sector. What is a chemical plant? It is the reproduction on an industrial scale of retorts, test tubes, mixtures. The reactions are the same, although we go from a few grams to thousands of tonnes. Once chemical experiments prove conclusive, we move on to the construction of these industrial installations.

What sort of work will this provide? Two types of work. First, the control and surveillance work by which laboratory processes are conducted and observed on an industrial scale and, it follows, maintenance work of the industrial infrastructure itself: making towers, tanks, pipelines, valves, electrical networks, metal infrastructure, etc. It is often forgotten, but the human hand is evidently never absent from an automated installation. Both types of work are equally indispensable.

Employers’ labor policies are highly differentiated for these two types of work. There is an ever-increasing tendency towards “outsourcing” everything from the business except “control” activities: cleaning always, transport almost always, and often maintenance and exploration. Employers have even attempted to “outsource” everything, that is to say using temporary workers for manufacturing. But, there was very firm trade-union resistance to this, and the attempts ended abruptly.

Employers claim that the division of these two types of employment – direct employment by the business for “the manufacturing process,” that is to say control, subcontracting for the rest – originate from technological constraints. This is false. Maintenance work can be planned and irregularities absorbed with stable employment.

From a strategic perspective in relation to the class struggle, that would evidently offer significantly fewer advantages to management. But there is nothing to prevent us from thinking in terms of maintenance, cleaning and transport “pools” conducting operations in a flexible manner as part of the business’s permanent workforce, employed on the same basis as other staff. Elsewhere, in other systems of social production, the ordinary personnel of the refinery have responsibility for all these tasks. For example, this is one of the problems for technology transfer between Italy and Poland. When Italy sells a ready-to-use refinery to Poland, it can be difficult to replicate staffing levels and productivity because the Polish refinery’s personnel directly carry out all the tasks subcontracted out by the Italian management.

In our countries the capitalist policy towards these two types of workforces is very different. Employers endeavor to consolidate this differentiation by playing on divisions that are central to the working class. Towards the core working class, the permanent staff of the Sacilor steelworks or the Shell refinery, the capitalist strategy aims primarily towards a form of integration. This does not mean that management do not confront the working class and the unions. Manufacturing workers lead often intense struggles. But there is, nonetheless, a management policy that aims to integrate, to some extent, the stable workforce with the responsibilities of the business. From this point of view, an enormous ideological effort takes place that is not without results. In the refineries, one often hears talk of “craft” in a narrow sense. “We are refiners”; you hear a CEO insinuating to a control room worker, “we are neither transporters nor street sweepers; it’s normal to subcontract out all that.” Likewise, in a cement works it is said that “we are cement makers,” in a steel works that “we are steel workers…,” etc. It comes as no surprise that these expressions, used by senior management to justify dismantling everything, should then be taken up and internalized by the workers.

The problem is that we know very well what “production” means in these continual process industries. Let us take an example. There is a unit with capacity for 100,000 tonnes of ethylene. For one reason or another (lack of demand) this unit only produces 50,000 tonnes of ethylene. One fine day, someone says: “We must go up to 100,000 tonnes.” The guys turn a few knobs and, from one hour to the next, output reaches 100,000 tonnes. Evidently, this would not be possible with the automotive industry. Here, the fact that it is possible to no longer have a direct relationship between physical movement and the volume of output creates a particular relationship to production, which is different from that in the classical industries. Of course, there are maintenance tasks that are more proportionate in their dimensions. And yet, the mere fact of “outsourcing” these activities from the business further extends the gap between the volume of output and the activity of labor-power. Numerous complicated and physically fatiguing aspects of work are outsourced. If we want to grasp the relationship, which still remains close, between labor-power and the scale of production, the whole must be taken into account.

I have spoken about the integration of the “core” working class of these industries. You need not imagine that this happens easily. People continue to defend their own interests, which are not those of the employer. One of the major problems of control room work, for example, is that it is carried out in shifts, which are called “3 x 8.” Workers follow three constantly changing shift patterns, and we know this has terrible neurological and physiological consequences, the body being unable to adapt itself to incessantly changing sleep and meal times. (Stomach ulcers are a shift work illness.) This stirs up discontent and, just recently, there have been important waves of strikes in the continuous process industries against shift work. This is one reason that studies have been conducted here and there over the past twenty or thirty years into how to bring shift work to an end here.

For the moment, employers claim that it is a technological necessity to work continuously 24 hours a day in these industries. Therefore, there are conflicts with numerous points of contention (over pay, differentials, career paths, professional qualifications, security etc.). This “core” working class cannot be defined as a completely integrated aristocracy of labor, despite some aspects of its ideology (“the refiner’s trade,” “the steelworker’s trade”…). But, it shows certain aspects of an aristocracy of labor in one sense, by barely taking charge of the interests of other sections of the working class incorporated within the same process of production: the debris, outsourced and temporary, of the small subcontracting outfits. But, that is where the least favored and the most exploited sections of the working class – immigrants, women, students are compelled to work. The most dangerous work and the hardest repression are found there. Often, it is not possible to join a union, and working conditions seem to have come straight out of the nineteenth century. Having the means to stop production and impose new regulations, the core working class is the only actual force that could effectively defend the interests of these other sections. On the whole, we note that the core working class barely takes any account of these “peripheral” categories though. More often than not the “core” workers do not even know what happens in the world of subcontracting in their own plant. For them, it’s just another type of work, carried out by another sort of worker (often immigrants). It is difficult to take account of it precisely, to know who employs them. A large operation is carried out, cleaning or maintenance? Four hundred guys zoom in, of which three hundred and fifty are temporary. They stay there a month then disappear. What becomes of them next? No one knows.…

It is very disturbing that this policy, which is systematic in continual process industries, has a tendency to spread across all branches of industrial production. This differentiated management of the working class presents such advantages for management that it is now seen to develop in industry where it cannot even be justified on technological grounds. The same thing is also done in the textile and automobile industries etc. The Japanese example leads the way. A core working class incorporated into an intensely paternalistic system is in evidence. This is surrounded by a spider’s web of subcontracting, with Korean immigrants or others participating in production without existing socially. In any case, the exceptional development of this system in Japan explains to a large extent the record productivity figures that so fascinate Western employers. Toyota appears to employ two times fewer people than Renault to knock out the same number of cars. But in fact, if you include everyone within the subcontracting system, the productivity figures are much more comparable. Some of the glowing visions of Japan, based on this sort of optical illusion, should not be relied upon.

Take the experience of continual process industries abroad, for example in Japan. Tougher government policy regarding immigrants and temporary workers are also elements that encourage employers to adopt a policy of structural division between the relatively stable working class, with which one tries to come to an arrangement (creating “careers,” negotiating with unions) and a whole section of the population for whom the argument essentially remains one about being fired, clubbed with batons and, in the case of immigrants, deported. There are abundant examples of the policy. In the textile industry subcontracting has expanded enormously with some extreme examples: incredibly small clandestine workshops (twenty undocumented Yugoslavs or Turks working twelve-hour days in a cellar…) subcontracting work from major outfits. A policy operates to this end even in the major public sector firms (coal mining, EDF, PTT).11 Just recently a serious accident occurred on Avenue de Latour-Maubourg in central Paris. A group of workers were installing telephone lines underground without any retaining structures. A concrete block fell and two Portuguese workers died. These workers installed telephones, so they worked for PTT. Yet, PTT immediately said, “This wasn’t us, it’s a matter for the subcontractor.” Even Imagining that the CEO went to prison, which didn’t happen, PTT wouldn’t give a shit. And yet, the work of PTT evidently involves the installation of [telephone] lines. Likewise, in the mines coal cutting is subcontracted. Not long ago a Turkish worker died on the coal face, crushed by a block of coal. A subcontractor employed him; he was not considered to be a miner. Yet, what could be considered more like the work of a miner than hewing coal from the face of the mine?

That is how employers come to break the gains won by whole sections of the working class. The same thing happened at Renault: upholstery work begins to be subcontracted. What do the women employed in the upholstery workshops do? They work as sewing machinists. Why not make them do it for small regional outfits? This is what happens at Sandouville. The immediate result: the girls who are going to make car seat covers lose Renault’s benefit package and can be paid SMIC.12 That can go a long way. A lot of things can be subcontracted, completely dismantling factories and workshops. In Italy this seems to be systematic.

And so we see a differentiated management policy for the two principal sections of the working class developing well beyond what would lend itself to production for technological reasons. If we want to be comprehensive, it is necessary to take account of the fact that, according to the logic of employers, this does not just take place within national borders. Just as you can install sewing machines in the home, so you can make t-shirts in Hong Kong. When the senior managers of an employer have all the elements to hand, they choose the most advantageous system that could be at a global scale. This is a cascading system made up of interpretation, exchange and subcontracts, and by which a part of production takes place abroad.

In short, the production of a French product often involves the workers of the large core enterprise, all the peripheral workers in France itself, much less well known, and a whole cluster of industries scattered throughout the Third World with much more appalling working conditions. This is the case in Morocco, in Tunisia, in Singapore etc. It has every possibility of developing in other Third World countries in which the governments wish to attract assembly or garment plants with a cheap workforce. Hence, Egypt has a project to create a free zone for the Suez Canal to this end.

When one wants to have an idea of the whole of labor-power that really contributes to the production of surplus-value for a particular product, all of this must be taken into account. All this web of relations defines the actual form in which capitalist production is organized.

Two Remarks

The first is on the terms “core working class” and “peripheral working class.” I employ these for convenience, even though in many cases the “peripheral” working class is the majority. In reality, there is quite a lot of diversity between concrete situations. The stable core is far from having the same status everywhere. As for subcontracting, it is based on capitalist competition between all the small outfits that put themselves forward to work for a large firm. The more difficult the situation is for SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises), the more the large company is going to put pressure on the market. What will happen in the SME? It could become a sweatshop, specializing in undocumented migrant labor and a trafficked workforce. A tragic situation of repression, pure and simple, sometimes organized in coordination with the recruitment systems of large companies. In 1971, when a Black man contacted the recruitment department at Berliet, he was told: “No work for you here, but they’re hiring at ‘52 Skid Row.’” The next day he ends up in a sweatshop and, in fact, still finds himself working for Berliet, but at lower pay, with no rights, etc.

There is another possibility: a variety of paternalism adapted for SMEs with skilled labor. The employer calls together his 30 craftsmen and announces to them: “Here we are guys, Renault offered us some work as subcontractors. Since there is nothing else on the market, we have to take it, even if it means working for ten hours a day, but only getting paid for eight. If we don’t take it, we’re going under.” It is not unusual to see workers accept such a situation in a period of crisis and even making representations to larger outfits to find business. This second possibility leads to the same result: obtaining a workforce for a low price.

So, this is a complex system of exploitation, but one that essentially tallies with the relationships between SMEs and large companies. On top of this, the government has already announced its intention for a major initiative and that this will be central to its industrial policy. Without a doubt, this system of relations between large companies and SMEs is called for to achieve a very granular fragmentation of the working class by so-called economic means. No one will believe that a salary increase will threaten to weaken Renault. On the other hand, the guys from the small outfit are put on notice to either bow down or face bankruptcy. How can an SME of 150 subcontractors bring Dassault to its knees? This is not possible. Only if workers, even at Dassault, take on the problems of subcontractors.

The whole structures of trade-union and workers’ organization would have to be reviewed to re-establish units wherever employers achieve this division. Union branches would be needed at each site, organizations operating across different outfits etc. For the moment, I repeat, this is out of the question.

As a second remark, we remain too often caught up with the image of the factory as the basic unit of production. Yet, in my opinion actually, the factory is in the process of disappearing as a significant unit in production as a whole. It has already disappeared to a large extent from the continuous process industries, where we talk in terms of clusters. For petrochemicals, for continuous process production, the unit is the cluster. This presents itself as an interconnection of numerous production processes, of numerous businesses. Among the prospects for the automobile industry is subcontracting abroad, in particular to countries in the East. For example, Yugoslavia specializes in the production of Peugeot engines. A combine will be created to produce, it is said, 50,000 engines required for its own cars and another 150,000 to resell under a long-term deal to the parent company which can then progressively reduce its engine production.

This creates a relationship of dependency for the country that accepts this agreement, since it absolutely needs to shift a disproportionate proportion of its production. It also provides the benefits of an assured source of procurement for the parent company. In general, the more you subcontract the more you destroy the factory as a distinct unit of concentration of workers in the hands of any individual capitalist, producing in a given location.

It is surprising that this evolution, however visible, provides the object of so little inquiry and analysis. No doubt, a degree of ideological blockage enters into how much ignorance there generally is about this. It is with difficulty that we in France recognize how different subcategories of the population function as a subaltern proletariat. We struggle to see the relationship between discrimination – because of age, sex, or nationality – and the structure of the labor process itself. However, this is the reality. There is a dual labor market: some have the capacity to negotiate while others do not, some have rights and others do not. In the final analysis, the state guarantees the organization of all this, as do international relations by means of immigration. The whole system constantly produces subordinate workers to occupy subordinate positions in the process of production.

England is the only capitalist country, to my knowledge, where this is studied in a manner that is at all systematic. Sociologists and economists, principally from Bristol, have made inquiries, in liaison with the trade unions or independently of them, into the petrochemical, automobile, and cement industries. They have studied divisions within the working class in England and the modes of its segregations, as well as the ways in which these divisions are inscribed upon the labor process. You could cite Andrew Friedman, Theo Nichols, Huw Beynon, Peter Armstrong. These are Marxists, but ones who say that you won’t find out how to account for all of this by clinging on to the text of Capital and the schematic interpretations that have been applied to it subsequently. Without trying to create new Marxist tools to take account of it, you’re left with too general an assessment of reality, and you are unable to account for what they call the micro-realities of the working class. For example, they critique Braverman, who sees Taylorism as the only mode of control and organization of workers’ labor. They try to define a more complex game between two strategies that they name “responsible autonomy” and “direct control.”

CC: What is the likely political impact of this evolution of the labor process?

RL: This is the big problem. But, one cannot deal with it just by considering these two terms. There isn’t a direct relationship between the transformation of the labor process and the political system. If you want to turn to the political system, a whole range of contradictions have to be taken into account, both within a society and at an international level, particularly given how the imperialist system functions in relation to the Third World.

For France, the whole evolution of society has to be taken into account: the mechanisms of the state, administration, regional contradictions, and forms of cultural domination. It’s a common mistake to want to draw inferences directly from the evolution of the labor process to one form of political representation or another. Doing so considerably impoverishes one’s analysis.

The truth is that these tendencies in the labor process, which I have just described, clearly inscribe themselves in the evolution of how the state is managed, as observed over the past decade. Let’s say the turning point was 1967 to 1969, the social crisis of the Gaullist regime and the General’s departure. In this period and in the years that followed, we contributed to the relative failure of a very centralized and authoritarian mode of managing the state. This had proven its effectiveness in resolving certain problems, but was no longer able to control certain complex aspects of society’s evolution.

The Gaullist system, in the strictest sense, gave way to a much more refined framework,13 which adopted much more flexible administrative, ideological and cultural means, as well as government by divisions and by lobbyists. This was based on the management of sectoral crises, so as to maintain a general equilibrium in the interest of the bourgeoisie. 1968 was the pivotal moment of this turn.

1968? There were two clearly distinct phenomena. A deep movement of discontent and revolt against rising unemployment, stagnant pay, oppression in the factories, which burst into an immense strike by workers. And a petit-bourgeois “happening,” which has held the limelight for ideologues and the mass media ever since, and will be marked by this year’s grotesque anniversary. But the explosion of students and intellectuals was something secondary, which effectively functioned to signal on the part of large sections of the petit bourgeoisie to say: “we no longer want to live like this.” This gave an extremely disorderly appearance at some stages to changes that took place thereafter, which have effectively modified (and strengthened) many aspects of bourgeois power.

On the whole, the working class obtained very little from the movement. On the other hand, things went much better for the petit-bourgeoisie. Much has changed in terms of morality, education, family lives, sex lives, the scope for different sorts of sociologists and psychologists to go and exercise their talents in different spheres of government. We have helped to reframe society on a vast scale in terms of medicalization, “social work,” urban planning, lifelong learning, research, etc. At the same time, this has reinforced the system’s overall control over the working class and the productive population, multiplying the warning signs and points of intervention for “social prevention measures,” and providing professional and social openings for a whole mass of intellectuals of the “humanities and social sciences” whose discontent made so much noise in May 1968.

We have witnessed a massive expansion of capitalism, of the capitalist mode of production, in the structures of the university and of research, and in cultural production, which had up until then maintained certain archaic characteristics.

If you want a condensed evaluation of May 1968, you could describe it as a shock to society that demonstrated that the excessively rigid Gaullist state system no longer corresponded with what was needed. This system was simultaneously called into question by the working class and by the petit bourgeoisie, and even by the haute bourgeoisie, which has begun to lose faith in it. The first political consequence to unfold from it came the next year. De Gaulle sensed the need for intervention to mediate between an overly rigid regime and a diverse population. He aimed to achieve this through his regional policy. But, other needs, those of a more complex modern technocracy, came into play: the referendum was lost and De Gaulle left. In point of fact, a period of eleven clearly defined years, from 1958 to 1969, came to an end. In a sense, there was a return to certain aspects of what existed before 1958, while incorporating the gains of the Gaullist period and lessons from the crisis.

From the point of view of the political institutions, what collapsed in 1958? A very flexible governmental regime, constantly displaced and returned to equilibrium by the mechanism of proportionality, frequent governmental crises that allowed any pressure group to make representations and modify the relationship between political forces. The government could be brought down by the bouilleur de cru.14 Within the bourgeoisie, this constituted a regime that was democratic enough. The different factions of the bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeoisie had their chance to impose this or that measure, but also to block this or that urgent reform.

This system of the Fourth Republic had its advantages except in the case of a severe crisis. However, France went through at least three major crises: the colonial crisis; the crisis of European competition (the Common Market treaty was signed in 1958 and there was fear of German competition); and the crisis of an aging economy, a bit like England now. France lost certain characteristics of an industrial country: agricultural production and primary materials made up too large a part of exports; there was a lack of major industrial facilities etc. At the most intense moment of this crisis, different sections of the bourgeoisie took fright and looked for a man sent by providence. In fact, from 1958 the Gaullist regime had largely settled these three problems. It pulled France out of the colonial trap and laid the foundations for a new form of French imperialism. It lay the groundwork for the conditions for European competition. It put in place a project of industrialization (under the aegis of Giscard d’Estaing, then Minister of Finance). In 1967 Stoléru’s “industrial imperative” appeared and this was the year of peak consolidation, of mergers, but also of weaknesses and unemployment. Thus a decade of tough politics to regulate major problems, one which involved treading on plenty of peoples’ toes. This tough policy only achieved its objectives by accumulating disaffection. Evidently, it did not provide a clear line of sight to steer between different strata of competing interests. In the end it blew up.

There is now a tendency towards a more flexible system with a supposedly “centrist” government and the possibility of overthrowing parliamentary alliances, but resting on an immense social framework principally put in place over the last ten years. The Fourth Republic has a certain number of characteristics inherited from the Fifth, but with a much stronger executive and the social framework developed since 1968, which was put in place with the help of a good part of the “anti-establishment” generation of intellectuals. (You see them in ministerial offices, the cultural sector, research departments: different systems of social management.) The Chaban-Delmas project laid its cards on the table shortly after 1968, and you hear talk of it again now.15 And I think, in effect, that this all merges well enough with the tendencies of the labor process and of production that I indicated: a politics of division, a highly differentiated management of workers’ labor-power.

CC: In your opinion, what would be the best thing for the children of 1968, today’s far-left militants, to do?

RL: I don’t see myself as a child of 1968. I made my choice several years earlier, in the Algerian self-managed farms, then in the French and immigrant working class. I find justification for my adherence to Marxism in all that I have seen and lived over fifteen years, not in a supposed moment of unrest.

That said, I don’t purport to have any overall claim to the truth or see myself in a position to hand out advice. All I simply have to say is that supposedly revolutionary or far-left forces are sorely lacking in concrete knowledge based on inquiries or connection to the productive system, which lies at the heart of society. This really seems tragically lacking to me.

As soon as a political problem arises (breakup of l’Union de la gauche on 22 September 1977,16 electoral setbacks, etc.), background analysis and investigation are cheerfully cast aside to instead reach a predictable, clearly defined position. Time after time you will see the same details come up, the same broad outline of events blown out of proportion. And yet, the PC, the PS, and the trade-union system, these are not easy things to know in depth, in terms of their evolution and how they function in our society today. And how many social forces and aspects of the system are purely and simply ignored!

It is extraordinary to see some people’s capacity to explain everything at any given moment, while often living on myths and essentially knowing nothing of political and social reality apart from what is fed to them by institutions of the media.

Afterward, they end up startled and surprised…

If I could express one wish, I would really like French Marxists to go out and discover French society…

– Translated by Paul Rekret and Eoin O’Cearnaigh

This interview first appeared in Critique communiste no. 23 (May-June 1978): 105-130.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | UEC is part of the first political youth organization of France, close to the French communist party. The UJCML was a Maoist organization founded in 1966 and banned by presidential decree in June 1968. Some members went on to found Gauche Proletarienne. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Robert Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor: Essai d’analyse matérialiste historique de la naissance du système productif soviétique (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1976). |

| ↑3 | Robert Linhart, The Assembly Line, trans. Margaret Crosland (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1981). |

| ↑4 | TN: The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies, abbreviated INSEE, is the national statistics bureau of France. |

| ↑5 | TN: Sacilor is a now-defunct French steelmaking group. |

| ↑6 | TN: The Amoco Cadiz was an oil tanker that ran aground on the coast of Brittany in 1978. It was the largest oil spill of its kind up to that date. |

| ↑7 | TN: Another French steelmaking group, which later merged with Sacilor. |

| ↑8 | CNPF (Conseil Nationale du Patronat Francais) was a French employers’ organization, it has since been transformed into the MEDEF (Mouvement Des Entreprises de France). |

| ↑9 | TN: Maîtres de Forges, the term used by Linhart here, refers to the dynasties that dominated the nineteenth-century French metallurgical industry. |

| ↑10 | TN: A reference to a 1976 media campaign launched by Lionel Stoléru, the French economist and then-Secretary of State for Manual Labor in the Giscard d’Estaing government. |

| ↑11 | TN: EDF and PTT: nationalized industries generating electricity and providing postal and telecommunication services, respectively. |

| ↑12 | TN: SMIC, or the Salaire minimum interprofessionnel de croissance, refers to the French minimum wage. |

| ↑13 | TN: We have translated the French “quadrillage” imperfectly as “framework” throughout. The term refers to a spatial or visual grid or partitioning, but is also sometimes used, most famously by Michel Foucault, to imply a detailed, systematic examination of that space. |

| ↑14 | TN: Artisan distillers with certain historic legal privileges dating back to the Napoleonic period, i.e. quite a niche interest group. |

| ↑15 | TN: Jacques Chaban-Delmas was Prime Minister of France from 1969-1972. |

| ↑16 | TN: A political coalition, bound by joint agreement to the Common Program, between the French Socialist Party and the French Communist Party lasting from 1972 and 1977. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine