This paper deals with the organization of work and the labor process in large complexes for oil refining and basic petrochemical production. It is precisely the similarity of labor processes (facilities for cracking or other methods, where a “process” is continuously operating, a set of chemical reactions triggered on a large scale and directed from control rooms) that leads us to expect this rapprochement. But it should be indicated that by doing so, we are pushing against the borders of the sectors or industries of production in the economic sense, as well as collective bargaining agreements (the petrochemical workers and oil workers are governed by separate contracts, even in cases where tasks and posts are strictly comparable). Moreover, at the global level of multinational companies, the relationship maintained between the price of oil and the income [la rente] of which it constitutes a significant portion is clearly inverse: the oil producers pocket an income that strikes the costs of basic petrochemicals. A higher price of naphtha puts the oil producers at an advantage and disadvantages the enterprises which use that naphtha to produce ammonia and ethylene. The situation is complicated because petrochemical subsidiaries of oil firms find their basic products being charged at full price by the parent company, representing a higher theoretical net cost at the subsidiary level, but an uptake [incorporation] of profit at the level of the group.

There remains a related labor process for all of these complexes: the operators of an oil-cracking refinery and those of an ethylene steam cracker are in charge of similar facilities. We will thus draw together here, in order to analyze the organization of work, the production of gasoline, fuel, naphtha, ethylene, butadiene, propylene, etc. – in short, the fuels and basic chemical products derived from oil, and certain products downstream of intermediary substances that they are immediately subordinate to.

The capitalists of the oil industry – and to a certain extent the petrochemical industry – are, as we know, masters of the art of obfuscation. Who is unaware of multiple examples of this in economic processes? Hidden apportioning of the market between the seven major companies of the cartel, the hiding of profits, dissimulation of the access price of crude oil, as well as the real costs of research and extraction, accounting juggling tricks between parent companies and subsidiaries beyond borders, etc. Fundamentally, the oil industry’s profits draw their source not from the usual mechanisms of the extraction and reallocation of surplus-value, but from the global distribution of the enormous oil rent. Rentier profits, first of all, with their parade of secret negotiations, relations of forces, arbitrariness, speculation. The petrochemical industry largely speculates on differential rents and rapid variations in the prices of products.

But what is true for economic processes is also true for labor processes. Here too, obfuscation appears as one of the operative conditions of the system of production: to the degree that many workers or technicians when asked about the organization of labor in their petrochemical refinery or production facility responded that there was no organization of labor properly speaking. Of course, there is a hierarchy, an organizational chart, posts, but those all have a largely formal character: the organizational chart is not respected, everyone has to more or less “make do.” There is work organization in the plant, you would often hear, but not at ours. Moreover, a term like “work pace” hardly made sense there: to double production of the product, all you have to do is pull four levers – try doing the same on an automotive assembly line!

An illusion, indeed – and the workers expose it themselves insofar as they clarify the operation of the labor process: this lack of formalism has its laws and establishes a system of constraint all the more powerful since it is unarticulated – thereby providing less leverage for clear-cut resistance. Constraint conceals itself either under seemingly voluntary choices (induced by the atmosphere of risk and environment of collective responsibilities carefully maintained by management) or under the so-called inescapable “technical requirements” (technological alternatives obviously not being brought to the attention of the staff who may try, on the occasion of an accident or a strike, to figure some out: don’t other catalyzer models exist, less sensitive than the one used by the firm, which management has emphasized how dangerous it is to stop and restart?). In this way, the organization of work, internalized by the workers or incorporated into technology, systematically dissolved in the general conditions of the plant’s operations, avoids straightforward description. It has to be reconstructed through analysis, in its hidden principles and effective functioning.

The very delimitation of the staff – the size of the workforce– contains its own share of mystery. Who is in the refinery and who is not? How many people must the firm have to produce 100,000 tons of ammonia? It might seem easy to answer this question for a determinate production facility, but that is in no way the case. The multiform development of outsourcing and contract work has allowed oil and petrochemical capitalists to “put out” [sortir] a growing number of activities to outside companies: routine or specialized maintenance, repairs, calibration, transportation, materials handling, or even some particular linked production. The staff of the petrochemical firm proper end up forming an organic nucleus [nuclei] around which gravitates a whole periphery of labor-powers highly varied in their skill (from manual laborer to researcher, by way of the highly specialized boilermaker) and status (from the stable employees of contracted firms or intermittent workers temporarily hired by a subcontractor), but who present the common feature of being excluded from the titular workforce of the production facility whose operation they nevertheless contribute to maintaining, often on an ongoing basis. The stable core of the petrochemical firm, whose staff size is easy to know, only forms a fraction, sometimes a minority fraction, of the overall labor-power [force de travail] implemented to ensure production. It even happens that workers from outside firms spend long periods in regular manufacturing posts – though this practice is generally limited by opposition from the workforce and unions. But these outside firms, with variable employee numbers, are not well known, including by the stable core of the petrochemical enterprise. However, the various types of laborers commingle daily in production sites [lieux de production]. But we will see that all measures are taken to maintain their separation.

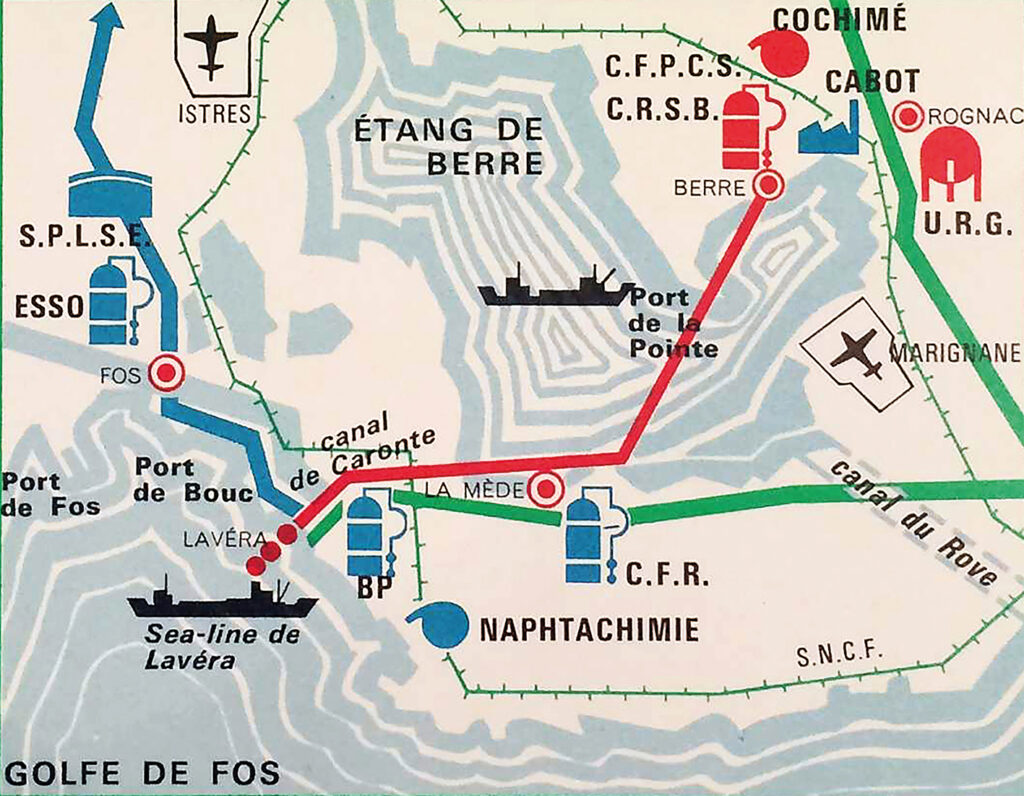

The production sites here present specific features which lend themselves to the highly differentiated management of labor-powers [forces de travail], and facilitate certain forms of compartmentalization. In the case of the petrochemical processing industry, the concept of the “cluster” [site], the entanglement of many firms and processes of production in complex relationships, is substituted for the concept of the factory, the industrial production facility common across the majority of industries, and which implies a relatively well-defined workforce and output. For lack of a multiform interconnection that is established with other, more or less geographically distant clusters (and this is most often the case), it becomes extremely difficult for a collective of workers to establish a precise relationship between their labor and a determinate production. Subjectively, a slippage takes place; the labor tends to be seen and described as management [gestion] – or surveillance – by a small group of workers from a fraction of the facilities where a flow of products, a certain number of transformations are maintained, whose nature is not always clear. In these conditions, the very idea of production is wrapped up in a degree of fuzziness [flou].

The Workers of the Petrochemical Firm vis-à-vis the Process and Their Control of the Facilities: What Kind of Knowledge?

The production process seems to be governed by a dual system of knowledge.

On the one hand, theoretical knowledge: the application of chemistry to a certain number of reactions that are triggered on an industrial scale. At the facility level, the engineers are in principle the assigned depositaries. This knowledge is listed in a series of guidelines/directives which define operations, describe the course of action, set the temperature conditions, pressure, etc., analyze the quantities and qualities of the products integrated into the process, and determine the expected result. The transmission of official orders of operation takes place via the classical hierarchical path, where the chief plays an important role (the daily supervisor makes assessments and transmits directives every 12 or 24 hours): the instructions culminate in their application by the unit group, the team of posted operators (head of post, operators, assistant operators, in varying numbers according to the size of the facilities and the complexity of the process: most often three to five persons in total). This transmission has a very formal character, and entails that it is regularly reported, usually in writing.

On the other hand, practical knowledge, acquired empirically on the fly by manufacturing workers – operators and assistant operators, but also heads of post – a knowledge that they transmit verbally between each other, which does not moreover rule out specificities from job to job. This practical knowledge is first built upon a concrete knowledge of physical networks, of tubes, valves, connections, etc., and is expanded through a wider comprehension of the processes (or at least of the relevant sections of the process) that produces the repeated experiments of facility’s operation and the many incidents which might arise. It ends up structuring and taking the form of a set of recipes [recettes]: to obtain a particular outcome, send this type of product at this moment; avoid heating this particular component at this particular time; watch over the behavior of the steam at this place; to “not be bothered,” maintain that pressure or leave this valve in this position, etc.

One might imagine that this practical knowledge boils down to a mere industry-specific explanation of theoretical knowledge. But that is not the case: there is a space of divergence. The two knowledges do not match: they are constituted on different bases and maintained by clearly distinguishable practices. There is a split [dédoublement] between the official operation of the production facility and its effective operation. In theory, it would proceed in a particular way stemming from the chemical theory of reaction. In practice, it proceeds differently, corresponding to the “expedient” [commode] operation fine-tuned through trial and error by manufacturing workers.

The management of the firm is well aware of this split. It even encourages manufacturing workers to learn in a spontaneous process: for example, by assigning installation and preparatory tests to workers, who will then be called upon to work there in manufacturing – an occasion to locate connections, pipes, valves, gaskets, welds, and become aware of the initial difficulties and weak points, an awareness that the majority of engineers will never have. More systematically, it develops “multivalence” (rotation from one workstation to another) and “polyvalence” (the performance, by the same worker, of several manufacturing and maintenance jobs).

Why is management so content with this autonomy of workers’ practical knowledge which could often come into conflict, to a certain extent, with the theoretical function of plants? Why does it not strive to obtain a stricter application of commands? Likely for several reasons.

In the first place, this system seems to be the most effective for production. A petrochemical refinery is not merely an expanded laboratory instrument. Performed at an industrial scale, chemical reactions carry a whole aleatory aspect that only practical experience can progressively learn to control. Manufacturing workers’ knowledge of petroleum and petrochemical processing is complete but it is genuine knowledge [un vrai savoir], indispensable to production. The passage from theory to industrial application is not a given. We have seen procedures perfectly worked out in the laboratory unequivocally fail during the passage to industrial scale. A famous example is the failure of the Dow Chemical facilities in the Cubatao petrochemical complex in Brazil. It was discovered that procedures that functioned in the laboratory did not work out for actual production and the investment was lost. This is also a fairly common practice for multinational corporations or engineering companies to test their prototypes in Third World countries that, if necessary, will endure the initial problems, failures, and losses. The practical expertise of petrochemical facilities that manufacturing workers collectively acquire over time constitutes an important asset for the firm and it is de facto strengthened through the development of polyvalence and multivalence, as well as through the relatively lax attitude that management takes toward the labor process. But it ensures, as a result, the prolongation of the fiction of a strict apparatus of directives and procedures conforming to the theoretical course of reactions and instruments of production.

A second advantage is drawn from this situation by management. In the case of incident or accident, responsibility is almost always diffuse and it is often easy to blame a worker who “did not follow the directives.” Better: the collective worker, continually operating in this atmosphere of illegality tolerated in relation to the formal description of the labor process, whose useful distinctions are endured so as to “not bother with it,” tends in many cases to “shut up” when an incident happens, internalizing a certain culpability. A kind of functional complicity, at the cost of snags and risks, is thus sought out and often won by the management. But there are times when this tacit complicity is broken when workers become aware of serious dangers, or in the aftermath of accidents, or in a general climate of industrial action. The system can then be turned around against the firm’s management, formally warned to respect its own safety regulations. Protest is all the more effective, then, since workers have a concrete knowledge of the effective operations of the facilities, their weak and dangerous points. Resistance can then take the form of “work-to-rule”: operating according to strict safety conditions and adhering to all regulatory procedures.

Let us listen to the description by a cracking refinery attendant [pompiste] of this double system of knowledge (theoretical and practical) and the double labor process (official and real):

The plant is so large, with so many details, that the supervisors can’t know all of them. Only someone who goes to that place daily can know what happens there. On the practical level, the one who goes there knows. The other might know the theory, but how that happens, that’s another story…

We have reached a point where the lead operator [chef de poste], who is worth their salt, winds up being more knowledgeable about the facility’s functioning, even when not comprehending the theory of petrochemistry, than the engineer who sometimes makes him do wrong things…And, ultimately, the chief operator is forced to do them knowing very well it’s a mistake.

There is a tacit agreement between the engineer and the chief operator. The engineer gives an order. He knows quite well that his order will sometimes be interpreted differently; but the other person does not say it – the one who performs the task. And everyone gets away with it alright. The higher-up gives their order, the other interprets it, nobody says anything, and then everything works out like that.

The circumvention of instructions or absence of instructions, empirical know-how: a workers’ autonomy exists in the facility’s functioning. This autonomy factors into management strategy, on the one hand, as well as into trade-union demands. It presents contradictory features: an element of pressure in the case of conflict and argument to obtain material advantages, but also a factor of consensus and integration within the enterprise.

Although the workers of the central hub of the petrochemical enterprise define themselves in relation to their hierarchy, to the “process,” to the instruments of production, they also define themselves in relation to the system of subcontracting [sous-traitance], if only because the parent company seeks to involve them as a stakeholder [partie prenante] in the organization of subordinate labor-powers and the vast subaltern proletariat employed across the cluster.1 The integration intensifies a mechanism of exclusion. And here, the systematic division maintained at the national level in the working class between those who have rights and those who do not (a division that today in the main intersects with the division established between national and immigrant workforces) plays a key role. It is to this mechanism that we now turn.

Petrochemical Workers vis-à-vis Subcontracted Workers: A Feature of Labor Aristocracy?

An overall analysis of the tendencies of the production and labor process in the petrol-based and petrochemical industry should take into account the set of factors that contribute to the growth of subcontracting: social strategies of the parcelization of labor-power, but also economic, fiscal, and technological strategies (some firms specializing in the maintenance and repair of complex equipment de facto function as technical pools for several refinery or chemical transformation companies, in which they sometimes have holdings).

We can nevertheless immediately distinguish between two types of labor-power employed through subcontracting in the petrol-based and petrochemical industry: on the one hand, very skilled personnel in maintenance, research or clerical personnel, commercial personnel (the subcontracting of a part of commercial management and marketing). On the other hand, the mass of unskilled workers from outside firms, to whom the lowliest tasks, the most unsanitary, the hardest, and often the most dangerous labor was relegated. In this mass, immigrant workers generally made up the majority. Still, there were also other recruitment sources: particularly in Southwestern France (Bourdeaux, Lacq, Aquitaine), there often seems to be unskilled French workers fresh from the countryside, or even students who have taken a temporary job – or young educated unemployed people. And women everywhere play an important role in subcontracting and temporary office jobs, at lower levels. But beyond this diversity, it appears broadly that the development of outside firms permanently employed across the cluster effectively transforms the division of labor in a thoroughgoing manner, more or less insidiously changing the function of workers of the petrochemical enterprise, and in many cases coming to load the position of the working class in this sector with ambiguity – posing a problem (more or less assumed) to industrial and trade union action.

For although on paper well-defined tasks are legally subcontracted, (cleaning, maintenance, shipping, etc.) in practice, one observes all over the place an extensive workforce, poorly protected, not directly employed by the refinery or plant, often composed mainly of immigrant workers, and which is responsible for the bulk of the work that is still manual. Where does maintenance end and manufacturing proper begin? In petroleum and petrochemical production, matters are far from clear. When manufacturing normally takes place, as we have already indicated, there are in principle few manual jobs to carry out. A slippage operates in this way: the manual tasks that are roughly tied to manufacturing are considered to be maintenance. A tendency arises to make the workers “from the enterprises” present in the complex – most often immigrants – do the largest number of manual jobs possible. In this regard, the French worker at the petrochemical refinery or plant will play in some cases the role of a de facto supervisor.

It is important to emphasize that, even in large petroleum and petrochemical facilities, the permanent shop floor personnel are never completely disengaged from manual tasks and might at any moment find themselves abruptly submerged in multiple demanding physical tasks – in the case of an emergency stoppage, for example. There exists, moreover, a hierarchy of participation in manual tasks among the permanent workers: the lower the level of “occupation” (assistant operator for example) involves a greater presence in the “structure,” inspections of installations, etc. The most sought-after promotion was a place in the control room, without any obligation to outside jobs. But the distribution of manual tasks or the external supervision of the “structure” also depends on the consensus established within the work team.

Here is how manufacturing workers of an important ethylene production facility describe their relationships with workers employed from outside firms in the cluster:

– Until now, when there were repairs to do, manufacturing personnel did the following: if there was a repair on a section of piping, they isolated the entire part in question, degassed it, and when the apparatus was inert, no longer at risk of exploding or causing problems, they gave the green light to make the appropriate repairs. But they absolutely did not care whether it was this specific joint, if the tapping [piquage] was at this particular spot…But now, they tend to make us do that. To make us inspect and verify that it’s done right. But in principle, that’s not our job. Ultimately…it concerns us to the extent that if it is poorly done we will perhaps be embarrassed. But we shouldn’t be forced to go check if they made good seals or things like that (because in the end we are urged to do that).

– What do you monitor there, the outside firms?

– The outside firms. In any event, here, other than the maintenance of pumps and monitoring devices, everything is subcontracted to outside firms.

– In sum, they want you to be both workers in the main enterprise and supervisors of others?

– Ultimately, we no longer know if they are the ones who want it. What is serious is that, since everything is done on the fly, it becomes habit. [ça entre dans les mœurs].

Another:

– Here, if you like, it’s the labor aristocracy, so the guys, you just have to push them a bit…And then there are a lot of immigrants.

– This gives a very precise content to the term labor aristocracy, if people are put in the position of monitoring the work of immigrants from outside facilities…

– And then, let’s say some things bring us into the circle. For example, there are safety jobs that are done: welding, machines like that. Okay. It’s clear that we are still closely affected by this. Insofar as we have a practical joker who walks around the facility with a blowtorch, there is a big risk: you can never say that there is never any gas in the facility. It is obvious that the guy (the manufacturing worker), when he goes to do a rotation in his sector, if he observes something that is out of the ordinary, he will instinctively flag it. It starts there and spreads further and further.

As a point of departure, there is the feeling of ongoing risk and a certain collective responsibility toward the facility (it happens that one hears a worker say: “I was still entrusted with a thing worth so many tens of millions…”). As the worker says in the interview, it is the beginning of a “circle.” You inspect to make sure everything is alright. Then you inspect a little more quickly. The already existing idea of superiority among workers of the permanent core strengthens this position. Management adds to it, maintaining a strict difference in status between its personnel and workers from outside firms, even if it means wielding a racist atmosphere when subcontractors’ employees are largely immigrants. A trade unionist remarks with some sense of powerlessness:

There are guys from the firms who work in appalling conditions, day and night, with no safety, without anything…But we can’t do anything about it [on n’a aucun moyen là-dessus]. At the level of the central enterprise and subcontracting plants, there is a safety committee. The unions have requested to participate in them, but that has been refused. They were told it didn’t concern them, it was not their enterprise…

You see a guy working in a location without a safety belt: if he goes down, he is going to crash down ten meters below. For some, obviously, this doesn’t raise any problems since “they are Arabs”…It should not be forgotten that as many of them are North Africans or immigrants, a problem of racism exists.

The plant, or rather the complex, reproduces here in a caricatural fashion the mechanisms of civil society as a whole: a status takes on so much value that it operates as a mechanism of exclusion and the rejection of immigrants serves the integration of the stable workforce in the parent enterprise.

What becomes clear is that Arabs are the only ones who do shit [faire des saloperies], what the people from this company won’t do…

We still have fairly good relationships with some Arabs because they’ve been there a long time and know the manufacturing people. But it’s always the relationship between a superior and a subordinate. It’s always that. They’re the guys who are there to do what we don’t do. What’s serious is that we feel that these people are afraid…He’s hurt, he feels bad, he’s going to take a dirty rag and wrap it around so it doesn’t bleed, and he’s going to trudge on so he doesn’t upset the crew chief…It’s perhaps logical, but we feel that they have a mentality of suffering, who suffer almost voluntarily in a sense, ultimately. Maybe it’s all the people around who do it, but in the end they suffer. When we cut ourselves, there’s no problem, we go see the shift supervisor, go to the infirmary. We’re divided about it: a piece of dust in the eye, you go to the infirmary. And they, on the other hand…a death, they’re taken away in the ambulance, it’s not a big deal, in any case, there will be another 150 or 200 who will enter. It’s appalling, ultimately. Like it or not, people in France are racist and that’s it. That happened to an Arab, so it’s no big deal.

We perceive through this disenchanted account the degree to which the system of segregation in the labor force, one of the functions of which is to strengthen the integration of permanently employed workers, thoroughly penetrates the personnel.

To overcome these separations, the trade unions in the enterprise have to be re-examined and envisage organizations at the level of the cluster, open to all workers. Such a transformation – which is sometimes raised by oil and petrochemical workers – would entail a veritable ideological upheaval [bouleversement].

Is the systematic division located in the petrochemical industry specific to that sector, or does it also constitute one of the current tendencies of capitalist work organization? The mechanisms of subcontracting and satellite firms in steel works need to be analyzed. And are we not observing similar phenomena in light manufacturing, too? The garment industry, for example, is seeing outsourcing and home-based work develop massively, at times clandestinely. Outsourcing should also be approached comprehensively, including through its international aspects.

An article by André Fontaine on Italy published in the March 6-7, 1977 edition of Le Monde discusses other forms of segregation in the labor force, through different routes, tending toward a dualist structure comparable to what we have encountered – a relatively protected core group and a peripheral mass with a subordinate status:

In the face of state incapacity, already burdened by audacious social legislation with too many encumbrances of all kinds, addressing underemployment, instant solutions have emerged. Millions of Italians work today “off the books” [au noir] at extremely low wages, for semi-illicit [à moitié clandestins] employers, who do not pay taxes or social security payments.

[In contrast to this sub-proletariat, there are the] “millions of workers in heavy industry, and more generally the workforce of the “protected” sector, benefiting from the sliding wage scale as much as the almost total guarantee of employment: the latter is such that we see employees who stop working sell their job post as elsewhere one might give up a ministerial officer position.2

The capitalist system of production reorganizes itself, as we know, through crises and the development of training mechanisms, and the transfer of surplus-value and profits, constantly traversed by class struggles. We often talk about the “new international division of labor”: would it not be appropriate to expand the analysis to all the modes of fragmentation of the production process, work, and labor-power, encompassing the labor force within the borders of a capitalist country?

– Translated by Patrick King

This text first appeared in Robert Linhart et al. (eds.), Division du travail: colloque de Dourdan, 9-11 mars 1977 (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1978), 21-32.

The translator would like to thank Patrick Lyons for invaluable assistance with the translation draft.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | Translators’ Note: “Sous-traitance” can mean outsourcing or subcontracting. I have chosen to use “subcontracting” when Linhart is dealing with the specific statuses among the workforce in the petrochemical cluster he is investigating, and “outsourcing” whe dealing with the more general employment strategy of hiring out third-party services. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | André Fontaine, “‘Eppur, Si Muove…,’” Le Monde, March 7, 1977. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine